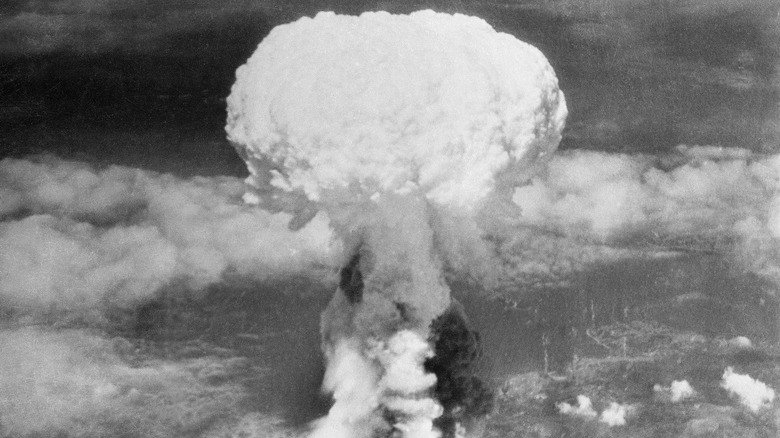

Is This What The World Would Look Like If The Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombings Never Happened?

It was the least grim of a series of deadly options. That has long been a common assessment of the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan in 1945. It was a view that was spread and believed at the time. President Harry Truman clung tightly to the rationale that the bomb swiftly won the war and spared countless lives. But the common view reckons without the heated disagreement within the Truman administration about the bomb's military usefulness and moral horror. It forgets the precarious state of international affairs at the time, where the Soviet Union was a dubious partner to the Allies and Japan counted on its neutrality in the Pacific. And then, of course, there is the matter of the horrific effects of the atomic bomb and the still-present specter of an apocalyptic nuclear war breaking out somewhere in a post-Hiroshima world.

And so, since the atomic age began, we have asked ourselves if Hiroshima and Nagasaki truly were the least of evils, the most expedient path out of World War II. We have also asked what the world might be like had the bombs never fallen. Would Japan have surrendered without further bloodshed? What path would atomic energy have taken into our lives? And would there have been a Cold War at all? We can never know for certain, but history provides clues as to a plausible alternate timeline for the 20th century.

Japan would have lost, one way or another

The rationale behind using the atomic bomb on Japan was that it would help speed along the end of World War II. It was never doubted that the end would come, or that Japan would fall. By 1945, the last Axis power standing was suffering the effects of a naval blockade and a devastating firebomb campaign. The Battle of Okinawa cost the Allies dearly, but it was a crippling defeat for the Japanese. Morale was broken in many corners of the country.

The question, then, is not whether Japan would have been defeated without the bomb, but how, and at what cost. It might have been done peacefully. The Japanese government was trying to find a way out of war by 1945. Their objection wasn't to surrender, but to an unconditional surrender that might expose Emperor Hirohito to a war crimes trial. And while they looked to the Russians as mediators, they preferred to end the war dealing with America rather than a Communist nation.

But significant elements of the Japanese military wanted to continue the fight, even if it meant utter ruin for their country; death, for them, was preferable to surrender of any kind. Had they prevailed, World War II might have continued on for at least another year, with tens of thousands of casualties on both sides before Japan was fully defeated.

Japan might have become a divided nation

While Japan hoped to use the Russians as a neutral party to negotiate a more favorable surrender with the Allies before the atomic bomb dropped, they were under no illusions about who they'd prefer to deal with in defeat. "We must end the war when we can deal with the United States," Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki advised after Hiroshima and Nagasaki (via the Los Angeles Times). To prolong the war, once Russia entered on behalf of the Allies, would almost certainly mean that not only would Japanese-controlled Manchuria and Korea fall within the Soviet sphere, but possibly Hokkaido as well, Japan's large northern isle.

Russian designs on Hokkaido may well have been less than fear and rumor have made them out to be. But if a draft constitution by the Communist Party of Japan is any indication, any Japanese territory under Soviet control or influence would have been radically transformed. Such a constitution would have rejected the sovereignty of the emperor, which was anathema to most Japanese and a major sticking point in surrender negotiations before the bomb dropped. It would also have meant adopting a communist system in a country that was largely anti-communist.

With America opposed to Soviet occupation of even Hokkaido, the communists wouldn't have been able to bring all of Japan under their influence. Much like Korea and Germany, the country might have been split, with a northern Japan in the Soviet camp and a southern Japan, presumably still a monarchy, under Western influence. And like other divided nations, a Japan torn in two could well have become a hotspot of the Cold War.

Nuclear weapons might have been deployed more regularly in war

Joseph Stalin was unimpressed by the atomic bomb, at least at first, according to Foreign Policy. He put more stock in armies and their mentality. But he was aware of the U.S. atomic program well before Hiroshima and did covet the bomb as a status symbol. That's unlikely to change in a timeline where America never deploys nuclear weapons against Japan. But had bombs never been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or had they been detonated away from population centers as a warning, the proliferation of nuclear weapons would have played out very differently than our own history, one where Soviet espionage brought them atomic power by 1949.

Demonstrating the power of the atom without widespread loss of life might have made international control over atomic energy, as proposed in the Baruch Plan, more feasible. But that assumes Russian recalcitrance in negotiations would be any less under those circumstances. Just as likely is a world where the Cold War superpowers both have bombs without an example of their use in combat to act as a deterrent against setting more off.

In such a world, the first bomb dropped may well have been during the Korean War. Or the Vietnam War. Or in any conflict of the 20th century where Cold War tensions drove hot clashes. In such a scenario, their first use may have inspired restraint afterward. But the bomb would have proliferated much further by that point, and hostile powers may have been unwilling to keep it in check if their enemies used it first.

Could the Japanese have developed an atomic weapon?

Much ink has been spilled on the possibility of a German nuclear program developing an atomic bomb before the U.S. In reality, the Nazis were never going to beat the Americans in that race, nor did they make much effort to do so. But what about the Japanese? Could the only nation to have experienced the horrors of atomic warfare become the first to hold the bomb, had things gone another way?

Toward the end of World War II, the Japanese navy approached Professor Bunsaku Arakatsu about developing a nuclear bomb, one of two such programs. Materials related to Arakatsu's efforts were recovered in 2015, as Japan was confronting difficult questions about its military and civilian nuclear programs. They included blueprints for centrifuges and a targeted date of August 19 for their completion. Arakatsu's work is one of the only surviving pieces of evidence regarding Japan's nuclear ambitions during the war; most were probably destroyed after the surrender.

Japan lacked the uranium needed to produce an atomic weapon, and its efforts to obtain it through its colonies did not come together in time. But had they been able to secure enough, and if U.S. bombings hadn't disrupted tests, Japan could have produced a bomb, if not on the same timeframe as the Manhattan Project. And they may well have used it against Allied forces if given the time to finish their program. Nuclear weapons on their own wouldn't have reversed Japan's lagging fortunes in 1945, but they could have prolonged World War II and intensified the horrors of the Pacific Theater.

Japan might have started its nuclear energy program sooner

Hiroshima and Nagasaki left a deep psychological scar on Japan. While government policies since World War II have dealt with the ambiguities of a nuclear-armed world where Japan's only defense ally is the United States, anti-nuclear sentiment is high throughout the country. Indeed, many Japanese, including survivors of the atomic bombings, have felt betrayed by the government's equivocating on the issue. Japan's nuclear energy program did not begin until 1966, and the 2011 Fukushima disaster prompted a fresh pause on utilizing atomic energy.

But it has been suggested that, without the twin horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan could have moved on to peaceful nuclear energy much sooner. In a world where America never dropped the bombs or demonstrated its power without casualties, Japan would still surrender to the United States and rebuild after the war. In this scenario, it would have embraced the peaceful use of nuclear energy. It might even have taken a leading role in innovating civilian uses for atomic power, free as it would be in this case from the memory of its darker purposes.