Weird Rules Olympic Gymnasts Have To Follow

There's no doubt that gymnastics is an intense sport. Any elite-level athletic discipline is, especially when it requires years of training, mental stamina, and top physical conditioning, and culminates in a televised competition that's watched by more than 3 billion people across the world. That competition is, of course, the Olympic Games. During the summer Olympics, gymnastics is often singled out as one of the star disciplines, with many looking on in awe as gymnasts perform feats of agility and strength, often in sparkly leotards that are a far cry from what it was really like at the first-ever Olympics.

For women, Olympic events include the dance-like (but still physically demanding) rhythmic gymnastics, as well as both team and individual events in artistic gymnastics focusing on vault, balance beam, floor exercise, and uneven bars. Male gymnasts compete in pommel horse, vault, floor exercise, rings, parallel bars, and horizontal bar. (They're currently not allowed to compete as rhythmic gymnasts.)

Some of the rules faced by Olympic gymnasts are pretty straightforward, even to the casual viewer. Falls garner point deductions, while stuck landings and well-done flips and turns earn high scores. But a more careful look at the ins and outs of the sport, and specifically the rulebooks and common practices of gymnastics organizations, show that it all gets complicated fast. Issues can come up with decorum, wardrobe malfunctions, and long-held gender norms. Ultimately, the rules of gymnastics may mean that things get a bit odd.

Don't show too much disappointment

It's obvious that Olympic-level gymnastics is an intense sport that demands not just top physical conditioning and endless hours of practice, but also determination and a steely desire to win it all. Few other disciplines expect competitors to keep it together to quite the same degree, however.

This rule is specifically outlined in a couple of places in the 2023-2024 rules and policies for women's artistic gymnastics, as determined by USA Gymnastics (and which American Olympic hopefuls must first abide by as they compete in their home country). The section titled "Athlete Members Rights and Obligations" maintains that competitors must "accept the received score without criticism or comment." What's more, they had better hold it together if they get hurt and especially if their routine does not go according to plan. As the obligations state, gymnasts absolutely must "Exhibit self-control and calmness in the case of a fall or injury."

Of course, emotional and mental resilience is a big deal in the sport. USA Gymnastics and other major gymnastics organizations routinely urge both athletes and coaches to deal with the high-tension emotions of the sport in controlled and (hopefully) healthy ways. Meanwhile, British Olympic gymnast Joe Fraser told the Olympics that he routinely deals with difficult feelings to the point of tears. Yet, though even greats like Simone Biles have been open about their fears and tragic real life stories, you will very rarely see them betray their emotions in the midst of competing.

If you lose a prop, you have to keep smiling

While it may seem like all eyes are on artistic gymnastics, don't forget the other major component of the Olympic competition: rhythmic gymnastics. Of course, if you ask anyone in the industry, like those rule makers at USA Gymnastics, the rhythmic portion is hardly for slouches. The discipline — currently reserved only for female competitors — combines both dance and artistic gymnastics and uses five different props known as "apparatuses": rope, hoop, ball, clubs, and ribbon.

But even world-class gymnasts can have butterfinger moments where they stumble or lose their grip. So, what's a rhythmic gymnast to do when a hoop goes flying out of her fingers mid-competition, or that elegant ribbon gets knotted or even caught up in a rafter? Olympic rules dictate that "if the apparatus breaks or is lost by a gymnast during an exercise, the gymnast is not permitted to restart the exercise." In other words, the show must go on. And, according to Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) rules, they have to "communicate feeling or a response to the music with facial expression" while doing this. So, even if a ball goes flying, you must continue smiling.

Olympic rules specify that a gymnast may get a replacement apparatus, but that will incur a relatively hefty 1.00-point penalty. If she drops an apparatus, that's another penalty ranging from a 0.50 to 1.00 point deduction, depending on how many steps she takes to retrieve it.

Visible underwear can garner a deduction

The reality of gymnastics is that much of the sport is about appearances. Judges may be looking for technical achievements, such as the predetermined difficulty of a move, or clear mistakes, like whether or not an athlete steps out of bounds or flubs a clearly defined move. But they will also be considering more subjective things like the elegance of a routine or the intensity of a gymnast's movements, neither of which are judging tasks that come with a clear rubric. Then, there's the fashion.

It's not just that gymnastics competitions include an array of eye-catching attire (though they very definitely do). Judges are also looking out for dress code violations. While such a ding may be annoying for a high schooler, it could knock off enough points that an athlete is left longingly staring at the medal podium because of an errant bra strap.

As U.S. gymnast Nastia Liukin told People ahead of the 2016 Olympics, most athletes wear underwear, but they're careful to select shades that blend with their skin tone and check that nothing shows. It's not just potentially embarrassing — visible underwear really can spell a deduction. Some athletes even reportedly get custom underwear made to help ensure that these garments remain hidden. That makes sense given that leotards are also typically custom-designed for these elite athletes, who are competing at a level where mere decimal points can stand between them and a gold medal (which is barely made of gold, anyway).

Food can be subject to complex rules

Whether these rules are set by the athletes themselves or their coaches, part of the reality of being an Olympic-level gymnast means abiding by some potentially strict dietary guidelines (though there are no official rules about diet). In 2021, U.S. gymnast MyKayla Skinner told Delish that she doesn't track calories or hold herself to an eating schedule, though she eschews caffeine and most forms of gluten while training. She also noted that she often goes for protein-rich meals before competing, a common dietary guideline for other athletes like gymnastic superstar Simone Biles. As Biles told Well+Good, she often enjoys a protein-enriched waffle in the morning, followed by similarly rich sources of protein for other meals, accompanied by plenty of fruits and vegetables.

Other Olympic gymnasts set up dietary regimens carefully tailored to where they are in their training and competition schedule, hardly anything like the standard non-gymnast who generally wants to eat healthier or work out more. However, it's worth noting that other gymnasts have a more casual approach.

Of course, many athletes today are also likely to tell you that dietary balance is key, with Biles herself openly enjoying treats like cinnamon buns. In fact, modern gymnasts are keenly aware of the dark past of the sport, in which athletes — under pressure to achieve a certain weight and performance level — have developed harmful and sometimes deadly eating disorders. Hopefully many now recognize that, at least in some cases, rules go too far.

If you need help with an eating disorder, or know someone who does, help is available. Visit the National Eating Disorders Association website or contact NEDA's Live Helpline at 1-800-931-2237. You can also receive 24/7 Crisis Support via text (send NEDA to 741-741).

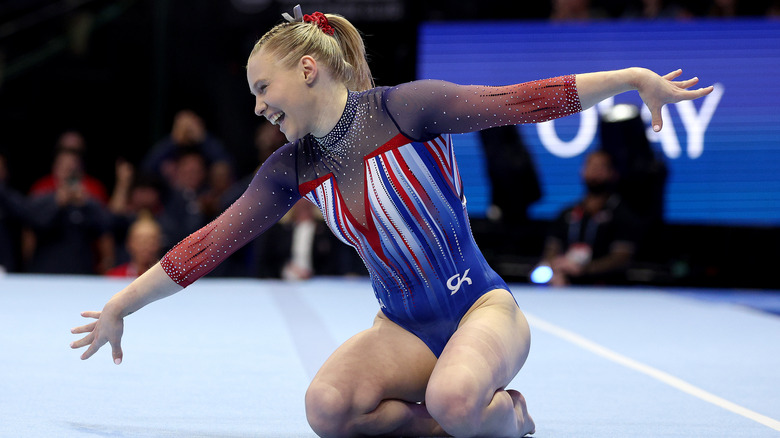

Getting the right leotard requires multiple complicated fittings

While it may not be an official rule of the Olympics, competing at such a high level practically demands that athletes get serious about gear. How serious? Let's start with as many fittings as a pricey wedding dress (and few people expect fully decked-out brides to do a back handspring on the big day, either). Those leotards are as expensive as some wedding dresses, too, at least when you add up all the pieces in a gymnast's professional wardrobe. Each U.S. team member gets 12 practice leotards ($60 to $200 each) and eight competition-quality ones (which typically clock in at $700 to $1,200 each, though the 2024 U.S. team's look would reportedly retail for $3,000 to $5,000 each — unsurprising when you note the thousands of crystals and hundreds of pearls on some leotards).

By the time Olympic-level leotards make it to competition, they've been designed, tested, redesigned, and individually constructed to fit the unique body type of each athlete. This laborious process helps them both stay within the rules of leotard appearances and remain as competitive as possible.

Olympic gymnasts go through about three fittings for a custom leotard (though some make it through with just two). What's more, they have to abide both by the rules of the Olympic committee — which dictates, among other things, that their uniform must display the flag or name of their country but not their individual name — and the final fashion say-so of their team coach.

Got a wedgie? Too bad

Highly designed as they may be, the leotards of Olympic gymnasts may still present the all-too-real issue of a mid-competition wedgie. And though you may pick yours out in discreet fashion, depending on the exact social situation and just how bad the wedgie in question is, elite competitors are often on the world stage. Simply reaching down and fixing the issue isn't necessarily an option when you have billions of pairs of eye upon you.

It's not just a matter of social decorum that keeps Olympic gymnasts from readjusting their leotards. Multiple sources have claimed that doing so can result in a very real points deduction — and who wants to lose out on a medal because they couldn't let a wedgie be? Writing for The New York Times, Leah N. Scarpa says that it would result in a two-tenths deduction at her state gymnastics meet, while Nastia Liukin told People that similar penalties would happen at the Olympics.

Liukin mentioned that athletes sometimes use adhesive sprays to keep everything in place. Meanwhile, Scarpa more directly blamed sexism and objectification for putting female gymnasts in that uncomfortable position in the first place. That objectification can be pernicious. For instance, while it's not an official rule, it is a commonly accepted convention that athletes should compete in long-sleeved but legless leotards. When German gymnasts competed in long-legged unitards at the 2021 Olympics, they openly said that they did so in response to entrenched sexism in the sport.

Hyper-excellence can be discouraged via official rulings

Simone Biles oftentimes presents a serious quandary for gymnastics judges. She is so frequently in such a stratospheric realm of excellence that it can be difficult to judge her work in relation to others who, despite years of training and dedication, can't take the title away from Biles (who nonetheless is human and had to pull out of the 2021 Olympic team finals due to stress-related performance issues).

More specifically, Biles has attempted moves so heinously difficult that some adjudicators have felt the need to underscore her work. Take her August 2019 performance in the U.S. National Championships, where she completed not one, but two incredibly complicated moves. The first, now known as the Biles II, garnered a difficulty rating of J (currently the highest such rating, as per the FIG). Yet it came as a surprise that another move, known as the Biles, was given a difficulty of H. The justification, according to FIG officials, was that giving it a more valuable difficulty score could encourage less-able gymnasts to attempt the move and risk serious injury — and Biles' vaults really can be that dangerous.

But critics have wondered if this is really meant to keep other gymnasts safe or if it's a sort of sour-grapes reaction to ultra-talented athletes like Biles. In other words, if Biles often utterly blasts the competition out of the water, perhaps the judges were motivated to level the playing field, fairly or not, via new rules.

Challenging a ruling requires you to pay up

If a gymnast or their coach isn't satisfied with a score, they're free to openly question the results ... so long as they're willing to pay up. After all of the money that goes into making an Olympic gymnast, from training to travel to those expensive leotards, officially challenging a ruling means that a team official must potentially pay hundreds of dollars. At the 2016 Olympics held in Rio de Janeiro, the going rate was $300 for the first challenge, followed by $500 for a second and $1,000 if a truly dedicated team went in for a third review.

Previously, coaches would have to pony up real cash but, by the games in Rio, that was changed to an agreement to pay later (perhaps because it did away with the unsavory visual of coaches handing dollar bills over to Olympic officials). As for who pays up, it's not the gymnasts themselves or even necessarily the coaches who are urging for a review. Instead, it's the national federation for that particular team that's on the hook.

The general idea of this rule is to cut back on unnecessary challenges, which can slow down competitions and make the whole affair look unprofessional. And if a challenge is successful, then the team will get its money back. If it's struck down, however, that money is kept by officials, where it's donated to charity (reportedly the foundation set up by the gymnastics international federation).

Appearance regulations have been controversial

Surely one of the most eye-catching things about the sports of gymnastics, at least after you've witnessed Simone Biles or other top athletes spinning seemingly effortlessly in the air, are the outfits. For many teams at the Olympics, the leotards will fall into a standard overall look (legless and with long sleeves is the norm) but can then come in a variety of colors and with embellishments that can glitter and dazzle beneath the bright lights.

Yet gymnasts are subject to appearance-based rules that go beyond sparkles. Some make sense from a practical standpoint, like USA Gymnastics' policy that athletes must have their "hair secured away from the face" and can't sport any jewelry beyond simple stud earrings. Anything else could reasonably be considered distracting to the athlete or even potentially dangerous should they fall.

However, appearance regulations go further, to the point where some have alleged that these rules should be more rightfully considered as Puritanical attempts to control women's bodies than attempts to keep a sport safe or even just vaguely decorous. For instance, in the same USA Gymnastics rule book, regulations state that leotards can't reveal hipbones and cannot be backless. Yet, it goes on to state that mesh or flesh-colored fabric in what would otherwise be open leotard sections is okay. Other dress code rules for the U.S. women's gymnastics team include bans on too-thin shoulder straps, tennis shoes, boxers, midriff-baring shirts, and other penalty-carrying clothes that have been deemed inappropriate.

Gender-based rules block gymnasts from some events

Even a casual overview of Olympic gymnastics will reveal an obvious rule: Male gymnasts compete in one particular set of events, and female gymnasts in another. Currently, men compete in six events (still rings, pommel horse, vault, parallel bars, high bar, and floor exercise) and women in four (vault, uneven bars, balance beam, and floor exercise).

To be fair, some events, such as still rings and pommel horse routines, do require extraordinary upper body strength that's more easily achieved by male gymnasts — though that doesn't necessarily mean women couldn't compete in their own events like in many other sports. In fact, at the 1948 Olympics, women did compete on rings. It's unclear what was behind the change between then and today, but some speculate that gender norms, not ability, shaped the dramatic differences between men's and women's gymnastics.

Similarly confusing is the current rule dictating that only women can compete in rhythmic gymnastics. Well, at the Olympics, anyway. In other events, men are welcome to perform — or at least they're trying to make headway. In Japan, male rhythmic gymnastics events have been popular for decades and incorporate tumbling movements not unlike those seen in artistic gymnastics. And in France, gymnast Peterson Ceus is a devotee of rhythmic gymnastics who is advocating for men to compete at the Olympic level and has even brought legal challenges to that point in his home country. Currently, however, the rhythmic gymnastics gender divide stands at the Olympics.