The Untold Truth Of Catherine De Medici

Catherine de Medici was born Catarina Maria Romula de'Medici to an Italian duke named Lorenzo II and his wife Madeleine de la Tour'Auvergne in 1519 at the height of the infamous Medici family's power and wealth. She seemed destined for a life of ease and luxury. Then, within weeks of her birth, she was orphaned. Her father died, reportedly of tuberculosis or syphilis or both, and her mother died of the plague.

"Queens of Infamy: The Rise of Catherine de Medici" records how Catherine was passed from her grandmother to her aunt and eventually became a pawn in a game being played out in the international stage. It was an unsettled but amazingly not an entirely unhappy childhood and one that probably went a long way toward preparing her for her future, which, to the shock of many, included marriage to Henry Valois, the Duke of Orleans, and decades spent as the queen consort and then regent of France. Catherine would also draw almost unprecedented ire and hatred from both her enemies and her own subjects. But, as is the case with many strong female leaders, much of the criticism laid at Catherine de Medici's door was down to sexist notions about a woman's place in the world.

Get thee to a nunnery, Catherine de Medici

Orphaned as an infant when her parents died tragically, Catherine lived for several months in Florence with Pope Clement VII, her distant relative and benefactor. Then rival factions overthrew the Medicis and Catherine was taken hostage and put in a convent. During her turbulent childhood, she would go from nunnery to nunnery, miserable at some, happy at others, and, according to Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France, always in flux.

The rebels who controlled Florence during this time despised the Medicis and wanted to see the entire clan and Catherine in particular come to ruin. "Queens of Infamy: The Rise of Catherine de Medici" says their plans for young Catherine included killing her, stripping her naked, and chaining her up to the Florence city walls. Another proposal was to toss her into the soldier's barracks where she would be treated as their personal sexual plaything. They figured, not only would she be forced to service them; she would also be ruined as a marriage prospect. Pope Clement wouldn't be able to arrange an advantageous union for her because her maidenhead would obviously be long lost.

Fortunately, neither of these sadistic scenarios came to pass. Instead, Clement was able to marry Catherine off to Henry Valois, Duke of Orleans and second son to King Francis I of France.

And you thought IVF was bad

For the first ten years of her marriage to Henry, Catherine failed to get pregnant. This confused the court, especially King Francis who took it upon himself to observe the young couple's wedding night shenanigans and, as reported by "The Machiavellian Matriarch Who Shadow-Ruled France Through Her Husband, Sons, and a Squadron of Spies," declared that "each had shown valour in the joust."

There were a number of factors working against Catherine's becoming a mother. Number one, Henry showed very little bedroom interest in Catherine. Instead, he saved all his love for his cougar mistress, Diane de Poitiers. Number two, Henry pretty much skipped town shortly after the wedding, heading to Italy, where he claimed to sire a daughter with a courtesan named Filippa Duci. It's very possible, though, that Duci's baby daddy wasn't Henry after all but another one of her hangers-on. For his part, Henry considered Duci's pregnancy proof positive that the infertility was all on Catherine's side.

Catherine clearly thought so, too, and, according to an article in The History of Urology, she took a number of drastic steps to try to up her fecundity, including drinking mule urine and dousing certain private areas of her body with bizarre things like cow dung and ground stags' antlers. Oh the joys of 16th century reproductive medicine.

It's not me, it's you

Catherine's husband, Henry Valois, would go onto become Henry II upon the death of his father, Francis I. Henry's prominence in the French monarchy required, among other things, that he and his wife produce an heir, something they failed to do in the first decade of their marriage.

Henry and others at court blamed Catherine who was desperate to maintain her place as Henry's wife. And that position was in serious danger. There was talk of divorce, both because of Catherine's apparent infertility and because her opulent dowry had recently been reduced to nothing. Royal marriage was all about babies and cash transactions. Trying to at least solve the first problem, Catherine enlisted the services of a famous physician, Jean Fernel, asking him to give both she and Henry a thorough physical examination.

"The Long Barren Years of Catherine de Medici: A Gynaecologist's View of History" informs us Fernel's exact diagnosis is lost to history, but it is now widely believed that the couple was unable to conceive because Henry suffered from a condition called hypospadias with chordee, a physical malformation that makes it difficult for a man to impregnate a woman. It appears that, upon the completion of his examination of the two royals, Fernel gave them some very useful advice, because shortly after Fernel's consultation, Catherine became pregnant with her first child. She then went on to give Henry a total of 10 children, seven of whom survived into adulthood.

With Catherine de Medici comes unicorn horn

When Catherine's cousin and benefactor, Pope Clement VII, went about trying to arrange a match for her, he knew he was going to have a tough time attracting the kind of mate that would help restore the Medici name. Catherine was rich, but she came of common stock and wasn't necessarily the prettiest little girl in the convent. So, Clement sweetened the pot, big time. The Florentine claims that when Catherine married Henry Valois in 1533, she brought with her a dowry that included 100,000 gold coins and lots and lots of jewels. According to Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis the First, Clement also gave King Francis, Henry's father, a unicorn's horn mounted in gold.

A year later, though, Pope Clement died, and new pope, Paul III, refused to pay the rest of Catherine's dowry to the French court. Francis was furious. He'd hoped that by marrying Henry off to a Medici, he'd be getting a some serious kickbacks. Instead, Catherine was penniless.

Divorce seemed imminent, not the least because, as "Queens of Infamy: The Reign of Catherine de Medici" puts it, Francis' mistress (he had one too, of course) reviled Catherine and spoke against her every chance she got. Catherine went for broke, begging at the feet of her king/father-in-law to be allowed to stay. Francis, a softy, couldn't stand to see a woman in tears and vowed that she would be allowed to stay on as Henry's rightful wife.

Catherine de Medici had to share the love

Henry wasn't faithful to Catherine. He began sleeping with his mentor, Diane de Poitiers, when he was a teenager and did not stop until his death, plus he openly bragged about siring a daughter out of wedlock with an Italian courtesan, going so far as to insist, according to historian Anne Theriault, that said daughter be named for de Poitiers. That's a jerk move on so many levels.

Catherine was not overjoyed at the fact that she had to share her husband's scattered attentions with another woman, but she also seemed to have understood the futility of trying to put an end to the affair, which Henry conducted in public without any pretense of shame. According to this look at Henry's relationship with Diane de Poitiers on Naked History, Henry often wore Diane's colors during jousting tournaments while Catherine sat on the sidelines, gritting her teeth and biding her time.

The Huffington Post reports Catherine eventually resorted to having spy holes drilled in the floor of her bedroom so she could observe Henry and Diane in their element. Adding insult to indignity, Catherine had to put up with Henry's gifting the house she wanted for herself, the Chateau de Chenonceau, to his mistress. Later, Catherine got her revenge. While Henry was on his death bed, ironically because of a jousting injury, Catherine refused to let Diane see him, and then she kicked her rival out of court and out of the chateau.

Catherine de Medici and women's work

When Catherine's husband, King Henry, died unexpectedly in 1559, Catherine became Queen Mother and her eldest son was named King Francis II. Francis, who'd recently married Mary Queen of Scots, was only 15 at the time and sickly. Catherine hedged her bets during Francis' short reign, closely observing court intrigue and advising her son in his dealings with the ambitious Guise family as well as the Huguenots, French protestants who resented the Catholic Valois rulers. When Francis died only a year after his ascension, Catherine was given the title governor of France and a host of new powers. The new monarch, Charles, was only 9-years-old.

Catherine impressed her fellow courtiers with her talents for statesmanship, playing rivals against each other for her own and her son's advantage. She also won a host of enemies when, as Maria Esquivel explains in her chronicling of the so-called St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, Catherine authorized a wholesale slaughter of the Huguenots in 1572.

When Charles died at the age of 23, Catherine's third son, Henry, ascended the throne. Henry, flamboyant and androgynous, was, according to the BBC, Catherine's favorite son. Catherine was not able to exert as much of her influence over Henry, but, prior to her death in 1589, she had left an indelible mark on the French monarchy, so much so that the decades she spent consolidating power became known as the Age of Catherine de Medici.

Catherine de Machiavelli

It's difficult to say who was more hated by their contemporaries — Catherine de Medici or Niccolo di Barnardo dei Machiavelli. Catherine was despised for her many attempts to hold onto power, which, according to Atlas Obscura, may or may not have included the murder of her rivals, and her failure to bring to an end to the decades-long Wars of Religion between French Catholics and their sworn enemies, the protestant Huguenots.

Machiavelli, a Florentine philosopher, writer, and politician, was hated in part for his infamous tome on how to rule the masses, The Prince, which, incidentally, he dedicated to Catherine's father, Lorenzo. In The Prince, Machiavelli appears to advocate for ruling one's subjects by deception and cunning. His seeming acceptance and championing of governing by guile gave rise to the term "Machiavellian," shorthand for the moral bankruptcy of the powerful.

The New Yorker contends that many of Catherine's subjects believed that her children carried a copy of The Prince with them at all times. The book was also been blamed at least partially for inspiring Catherine's decision to give the go ahead for the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of the Huguenots in which hundreds of men, women, and children were slaughtered on the streets of Paris, having gathered there to witness the wedding of Catherine's daughter, Marguerite, to the Protestant Henry, King of Navarre.

Catherine de Medici was mommy dearest

Catherine's relationship with her daughter, Marguerite, was incredibly fraught, and Marguerite detailed her many problems with her mother in her published autobiography, The Memoirs of Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre. One of the main sticking points between mother and daughter was Catherine's decision to arrange a marriage for Marguerite to the protestant Henry, King of Navarre, in an attempt to broker peace between French Catholics and their Huguenot rivals. (The French Wars of Religion had been raging for decades and Catherine was anxious to end the bloodshed.)

At the time of her wedding, though, Marguerite was in love with Henri, Duke of Guise, a member of a family Catherine openly loathed. Henri Guise had another strike against him in Catherine's book: he was, obviously, not Marguerite's husband so when Catherine and her son, Charles, caught Marguerite in bed with Henri, they immediately started beating her. It was not, according to "Queens of Infamy: The Reign of Catherine de Medici," Catherine's proudest moment.

To Catherine, who had dedicated her adult life to preserving her family's power and its divine right to the throne, Marguerite's behavior was unforgivable. How could she endanger the Valois legacy over a little thing called love? Inconceivable.

If the shoe fits...

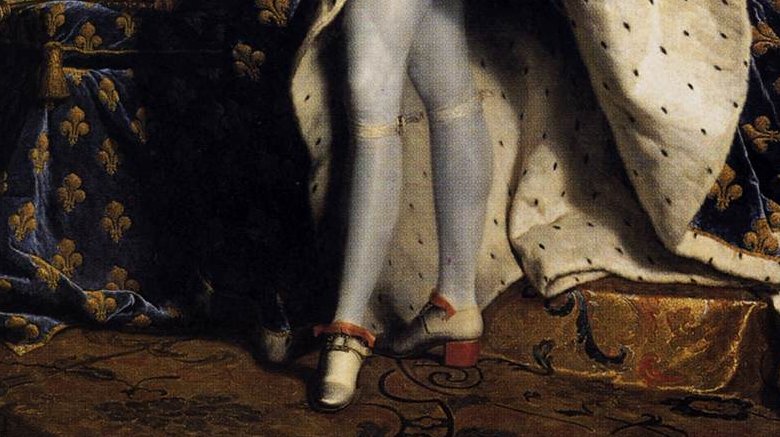

Catherine was given many nicknames over the course of her lifetime. Some called her the Serpent Queen, others the Black Queen or the Merchant's Daughter. Still others referred to her as the Maggot from Italy's Tomb, which is so metal. The nickname she was least likely to object to was the Mother of the Modern High-Heeled Shoe. The latter, according to an ABC Radio Perth report, comes from Catherine's insistence on wearing the Renaissance equivalent of stilettos at her wedding to make her appear taller.

Catherine was not known for her beauty. As Prisoners of Eternity reports, Catherine was often described as polite, well-mannered ... and rather bug-eyed, the protruding orbs said to be a hallmark of the Medici physiognomy. She was also very small, hence the heels. Prior to Catherine's donning them for her marriage to Henry Valois, high heels were an accessory worn only by men who strapped them on to prod on horses. In addition, they made vain men feel fancy. (See Louis XIV.)

While men wore high heels, women wore platforms that were, in effect, stilts, often falling while trying to walk in them. Women sometimes suffered bodily harm while wearing platforms and were even know to miscarry after especially bad falls. By insisting on actual high-heeled shoes for her wedding, Catherine was a pioneer, making fashion a little safer for her sisters.

Catherine de Medici had her own squad

Having observed the power her husband's mistress, Diane de Poitiers, held over her husband, Catherine gathered together a group of attractive and allegedly promiscuous young women to help her hold onto power. As All That's Interesting explains, the women drifted in and out of court in silk and gold robes, alternately spying on and sleeping with Catherine's political enemies and sometimes even her friends.

A court rumor suggested that one reason she was permitted to take over as regent after her husband's death was because she deployed a member of her squad to sleep with the decision makers. Catherine was also said to have directed one of the so-called flying girls, Charlotte de Sauve, to seduce her own daughter's husband, Henry of Navarre, as well as the Duke of Alecon (who'd been hatching a plan to displace Catherine), thereby working the two men against each other. Catherine's daughter, Marguerite, was understandably not thrilled with a scheme that involved her mother seducing her husband by proxy.

The members of the Flying Squadron were supposedly so beautiful and so good at their jobs that they were known to make men see God, or at least worship Him in a different way. According to an anecdote in "Queens of Infamy: The Reign of Catherine de Medici," squad member Isabelle de Lemeuil managed to turn the devout Huguenot Louis de Conde Catholic for a while. Mon dieu!

Catherine de Medici: black magic woman

Catherine de Medici often alienated the regulars of the French court in her pursuit of power. It got so bad that she was blamed for the often convenient deaths of her enemies. Case in point, Jeanne d'Albret, prospective mother-in-law to Catherine's daughter, Marguerite. D'Albret had left court years before, turned off by Catherine's clique of pretty and promiscuous young women, the Flying Squadron. Catherine then talked d'Albret back into her good graces by promising that, should her son, Henry, King of Navarre, marry Marguerite, he could remain a Protestant. Then, just two months before the marriage was to take place, d'Albret died in Paris, shopping for wedding clothes. According to this Atlas Obscura article, courtiers claimed Catherine poisoned d'Albret with a pair of tainted gloves.

Catherine denied such rumors, of course, but her case was not aided by the fact that she was openly obsessed with prophecy and the occult. In her exploration of Catherine's later life, Anne Theriault writes that not only did Catherine claim to have had a dream that predicted Henry's death in a jousting tournament, but she was said to wear an amulet made by Nostradamus containing both human and goat's blood. Also, just before her husband's mistress was to move into Chaumont, a home owned by the Valois family, she made sure to redecorate the place in pentacles as part of a scrying ritual.

Catherine de Medici was the mother of modern ballet

Catherine de Medici was known primarily as a smart and sometimes ruthless leader, the woman behind the men of the Valois court, but she was also a passionate supporter of the arts, and it was during her time as governor of France that ballet as we know it really began to flourish.

Her most influential contribution to ballet was, according to Ballet in Western Culture, bringing famous Italian dance masters to the French court. There, renowned Milanese choreographers like Pompeo Diabono and Cesare Negri helped transform ballet from a purely French form into something more cosmopolitan and global in scale.

Catherine invited these masters to put on lavish performances at court festivals, which, as "Catherine de Medici: Patron of the Arts and Follower of the Occult" puts it, she planned and sponsored in order to show off France's cultural and financial wealth. The performances, as well as the festivals themselves, helped give birth to modern ballet. They also solidified Catherine's reputation as one heck of a hostess.