What It Was Like The Day Bruce Lee Died

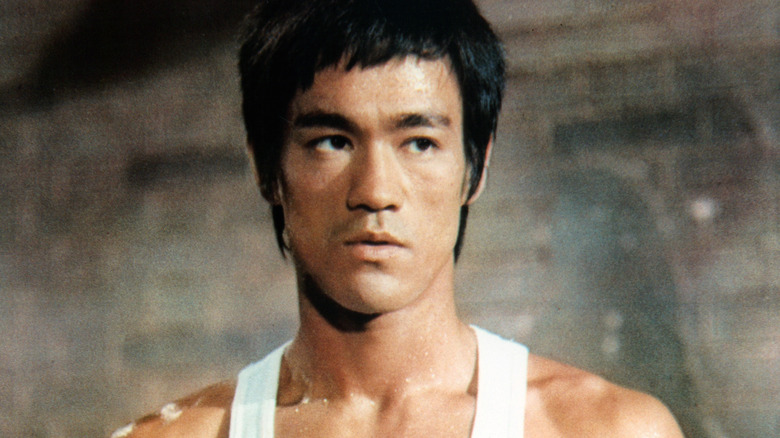

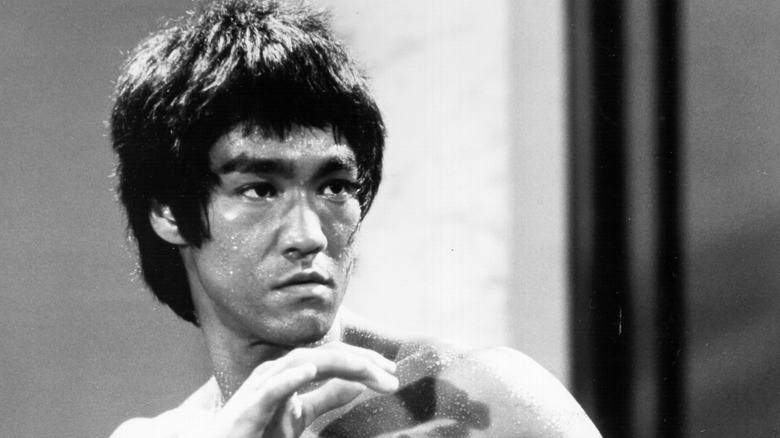

To those who are particularly in tune with the wider world of entertainment and popular action movies, the date July 20, 1973, might set off more than a few alarm bells. And if that date didn't immediately raise some flags, here's the short answer: It's the day that famous movie star Bruce Lee suddenly died.

If the 1970s Hollywood scene isn't your forte, don't fear. Lee was an American-born actor who grew up in Hong Kong, where he fell in with a rough crowd, fighting on the streets alongside gangs. After being sent to the U.S., he began teaching his own brand of mixed martial arts and soon caught the eye of Hollywood executives. In 1966, Lee landed a role as the sidekick in "The Green Hornet." Short of work after the show's cancellation, he returned to Hong Kong and became the breakout star of several movies — released as "Fists of Fury" and "The Chinese Connection" in the U.S. He shortly created his own production company, but just days before the release of "Enter the Dragon," he died suddenly, at only 32 years old.

Lee's death prompted plenty of discussion, but it's worth noting that other things were going on in the world at the exact same time. Some rather big things, too, which have less to do with entertainment and more to do with, in some cases, domestic or international politics. Mid-1973 was a busy time, to say the least.

Bruce Lee's mysterious death

Of course, the truth behind Bruce Lee's tragic death was a big deal to movie-lovers at the time simply for his fame; after all, Lee's name has lived on for years after his death. But there's more to it than fame. There's mystery involved, too.

Lee had been experiencing headaches and seizures in the months leading up to his death, with a hospital visit diagnosing him with cerebral edema, or a swelling of the brain. He was discharged and kept working, but on July 20, in the midst of working on the movie "Game of Death," he complained of a headache and lay down for a nap. But he never woke up. After being found unconscious, he was taken to a hospital and pronounced dead upon arrival. After a funeral in Hong Kong, Lee's body was returned to Seattle for burial.

The mystery comes from the exact cause of his death, however; everyone acknowledges that it was cerebral edema, but the cause of the edema itself is a longstanding point of contention. At the time, doctors ruled that it came from some sort of reaction to Equagesic, the painkiller Lee had taken for his headache, but that wasn't the first time Lee had taken that medication. Other people speculated that cannabis had something to do with it, as it was found in his system at the time, but doctors denied the possibility. Even in 2018 and 2022, new theories cropped up, claiming that overexertion and heat stroke or drinking too much water, respectively, could've been to blame.

The hijacking of Japan Air Lines Flight 404

On the exact same day that Bruce Lee died, there was quite a bit of drama to be had high in the skies. Japan Air Lines Flight 404 had taken off from Amsterdam for Tokyo via Anchorage when Schiphol Airport's air traffic controller realized via secret code that something was wrong. Five terrorists — four from the Palestinian Liberation movement (one of whom died in a grenade blast during the skyjacking) and one from Japan's extremist Red Army group — had taken control of the plane and diverted its course, taking the 123 passengers and 22 crew members toward the Middle East. (All of this despite the Israeli secret service tipping off Amsterdam officials that a skyjacking was imminent.)

From there, the skyjacking was far from easy to resolve. The terrorists struggled to find a place to land, being rejected by both Beirut and Damascus airports, eventually being allowed to land in Dubai. Then-Minister of Defense Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum entered into negotiations with the terrorists, where Red Army member Osamu Maruoka demanded both refuge in Dubai and the release of Kozo Okamoto, who had been apprehended for the deadly attack at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv the year prior. Those demands couldn't be met, however, and all the skyjackers got was more fuel for their plane. They took off yet again, this time landing in Benghazi, Libya, on July 24, at which point they released the hostages and bombed the plane, destroying it.

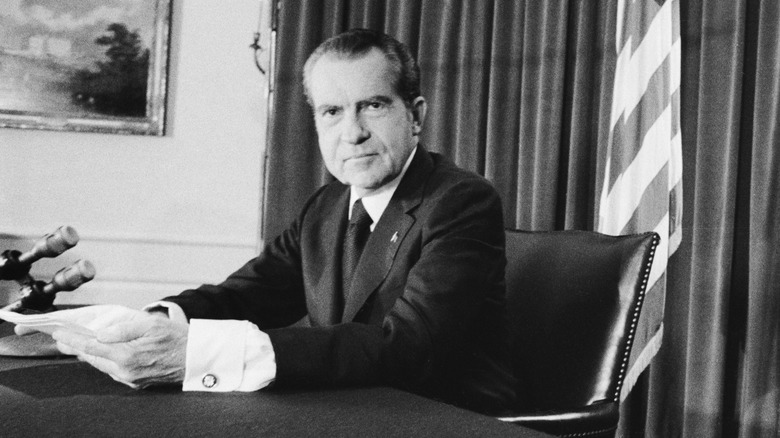

The Watergate Scandal was heating up

If you're looking for infamous presidential scandals, you really need look no further than Richard Nixon and the secrets of the Watergate scandal. True, this whole thing started considerably earlier, with Nixon sending a team to bug the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in D.C.'s Watergate office complex in 1972 (a response to the leaking of the Pentagon Papers a year earlier). But in July 1973, Nixon himself was dragged into the fray.

In 1971, Nixon had secretly installed a taping system in the White House, intending to use it to document policy decisions yet believing its existence would never become public knowledge. But then the Watergate trials started, broadcast live to the whole nation. On July 16, 1973, administrative assistant Alexander Butterfield testified to the Senate that this secret taping system existed, recording every conversation had by the president — an explosive revelation to the American public. Only two days later, Nixon ordered that the system be disconnected, and over the next few months, investigators tried to get their hands on those tapes, only for Nixon to repeatedly refuse. During that time, the suspicions surrounding Nixon only grew, as more and more people began to believe that the president himself was involved. (A correct assumption, in all fairness. Nixon had been involved with the original break-in as well as the subsequent bribes and cover-up.)

Trust in the presidency steadily fell apart from there, and Nixon finally released the tapes in April 1974 before resigning later that year.

Operation Wrath of God was about to make a fatal mistake

This one has some history involved. At the 1972 Munich Olympics, members of the extremist Palestinian organization Black September snuck into the Olympic Village, taking members of the Israeli delegation hostage. Ultimately, all of the hostages were killed, and the surviving terrorists went free. Amid the tragedy and controversy, the bodies of the Munich Olympics Massacre were given their last rites, but Israel was hard at work. They wanted justice, going about it by starting Operation Wrath of God, a Mossad mission to exterminate the Black September members responsible for the attack.

Over the next year, their revenge was brutally effective, but that changed in July 1973. While in Lillehammer, Norway, Mossad agents received intelligence that led them to believe they'd found one of their targets — Ali Hassan Salameh, otherwise known as the "Red Prince." They pulled off their hit on July 21, shooting their target in front of his wife before scattering almost immediately. But later news reports proved they'd made a horrible mistake. The man they had killed was, in fact, an innocent civilian named Ahmed Bouchiki, who just so happened to resemble Salameh and was only seen talking with a Palestinian courier by complete coincidence. Six of the Israeli agents were apprehended in short order, five of whom went to trial the next year.

The incident became known as the Lillehammer Affair, and Mossad officials immediately suspended Wrath of God operations (though it took decades for them to offer compensation to Bouchiki's family, albeit without ever taking responsibility).

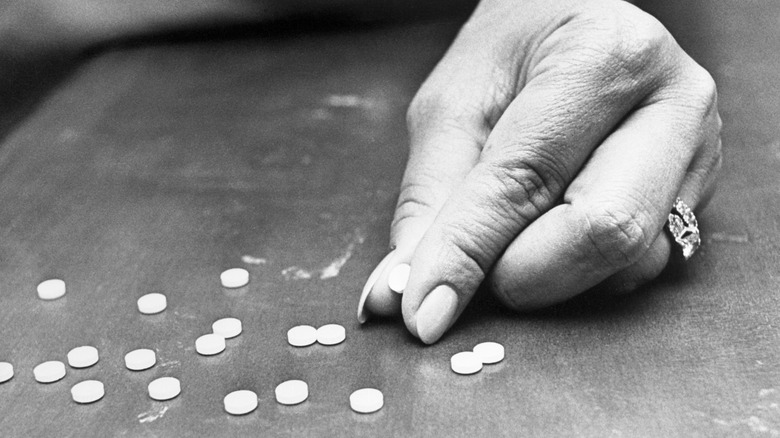

Thalidomide court proceedings were coming to an end

The Thalidomide scandal has a rather disturbing history behind it, as well as tragic consequences. In the 1950s, a miracle drug called thalidomide entered the market, said to cure the symptoms of pneumonia, colds, and even nausea. Consequently, plenty of pregnant people began taking the drug — distributed by the Distillers Company in the U.K. and said to have zero ill effects. The safety of the drug was hugely overestimated, however, and babies were born with serious impairments. The link wasn't found until 1961, at which point the drug was pulled from the market.

Some pharmaceutical companies were brought to trial, and in the U.K., Distillers reached a compensation deal with victims. But many thalidomide victims in the U.K. didn't think it was enough, starting a campaign against Distillers for further compensation — a campaign that became rather well-publicized by the media.

Following a protracted legal battle, another settlement was reached on July 30, 1973, finally ending a decade of strenuous negotiations. For the victims, this was seen as a victory, with Distillers agreeing to pay £6 million split among them (with the first payments delivered over the next few weeks) and set up a £14 million trust fund that would be used for future aid as necessary. For the most part, the public viewed the plaintiffs as heroic, standing up for themselves as even more families came forward with their stories. Distillers representatives, of course, saw things differently, denying the company had done anything wrong and claiming that the legal proceedings had only delayed financial compensation.

Patrick Mackay started terrorizing London

True crime is quite the hot topic these days, but that doesn't mean that every story about a serial killer is particularly well known. One of England's serial killers has actually managed to slip from the public consciousness: Patrick Mackay. Though, to be entirely fair, his exact list of crimes is a matter of debate.

Here's the story. Mackay had several run-ins with the law when he was still a child, was clinically diagnosed as a psychopath when he was just a teenager, and was institutionalized in 1968. All the indications of future, violent behavior were always there, but he was released in 1972. For the next few years, he wasn't on the radar of law enforcement, but the gruesome 1975 murder of Father Anthony Crean led investigators right to him. Upon being caught, he started confessing to a whole host of other crimes, and ultimately, he was convicted of three murders: Adele Price and Crean in 1975, and Isabella Griffiths in 1974.

That wasn't all he admitted to, though. In fact, he told investigators about eight other victims. The first was a young German woman named Heidi Mnilk, who had been stabbed on a train and thrown to the tracks, where she was found on July 8, 1973. On July 20 that same year, a woman named Mary Hynes was found violently beaten to death. Six more followed between then and 1975, though Mackay later retracted those confessions, and they officially remain unsolved, as he could never be conclusively tied to them.

Greece's political system was in flux

Here's something of an interesting historical fact: Greece was actually ruled by a monarchy until mid-1973. Maybe a little unexpected for the country that's often credited with essentially creating Western democracy, right? As it turns out, though, Greece actually had a monarchy between 1863 and mid-1973 (with a break between 1924 and 1935). Well, for the most part, at least.

Technically, the military had staged a coup back in 1967, ousting the king, who fled the country. In early June 1973, the military government made a bold announcement: It had officially abolished the monarchy and was prepared to turn Greece into a republic. All it would take was for the Greek people to approve the decision in a referendum that would ultimately take place a few weeks later. During that time, however, there was a decent amount of back-and-forth discussion as to what should be done. The exiled king Constantine II (pictured above) cast doubt on the intentions of the referendum, pointing to censorship and propaganda as it had been perpetuated by the military government and claiming that asking people to vote for a regime that had seized power was strangely ironic. On the other hand, however, Constantine II himself had never been hugely popular with the people. Sure, there was little open hostility toward him (aside from opposition within the military regime), but his relatively lukewarm reception made it hard to actually determine his standing with the public.

That said, the monarchy was dissolved as a political entity, with the military leadership following suit a year later.

Space exploration was still going strong

There are plenty of smaller time periods and events associated with the Cold War (some of them fairly messed up), with one of the most prominent ones probably being the Space Race. True, if you wanted to be technical, the Space Race more or less ended when Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969. That didn't mean space exploration just stopped, however. There were plenty of space missions launched by both the U.S. and Soviet Union throughout the 1970s — even a few joint ventures as the decade progressed.

Mid-1973 was actually a pretty busy time for both countries in the space exploration department. On the American end, you had the Skylab missions — essentially, the first attempt at a long-term space station. Almost like the precursor to the International Space Station, in a lot of ways. To get more specific, July 28, 1973, was the launch date of Skylab 3, which sent three astronauts to space for a record-setting amount of time: nearly 60 days

The Soviet Union wasn't slacking either; while the U.S. was experimenting with long-term stays in space, they were launching a number of Mars spacecraft. This was technically a longer mission that spanned from 1973 to 1974, but on July 25, 1973, Mars 5 was sent on its long journey through the cosmos. The actual probe wouldn't arrive in Martian orbit until February of the next year and it malfunctioned after a few days, though it did return some atmospheric data and a few photos of the red planet's southern hemisphere.

The founding of the ESA

The Space Race (and the technology it produced) is pretty heavily focused on the U.S. and the Soviet Union — Sputnik and the Apollo missions and such. However, they weren't the only two countries getting into the game. Mid-1973 actually marked the time when Europe on the whole would officially enter the scene.

Well, technically, Europe had started looking into space exploration slightly earlier, with the European Space Research Organization and European Launcher Development Organization around in the 1960s. But as the 1970s rolled around, there was a need for new programs that would push the boundaries. European leaders on the whole wanted to become a serious presence when it came to space exploration and technology, rather than simply a contributor to foreign projects. The European Space Conference was held in the summer of 1973 to outline the exact trajectory for those goals, and there, they settled on three related projects by July 31, one of which was a European Space Agency, known now as the ESA. In short, the plan was that it would be ready to go by April 1, 1974, and build on those older organizations, also promoting unity among the nations of Europe. And given it's still around, its 22 member nations all actively taking part in launches and missions to this day, it suffices to say that they've done decently well at that.

The U.S. economy was distressingly strong

In early July 1973, a decent amount of the American population was benefitting from a relatively extended period of a robust economy, and many people were debating whether that was just the calm before the storm. Sure, there was a lot of demand for a bunch of consumer products, enough supply to meet that demand, and a fair few jobs open for everyday folk, but there was a growing sense of dread that things would take a turn for the worse. For the most part, people expected that there was a recession on the horizon — even if they weren't sure how bad that recession would be. The eye of the public was on the numbers (inflation was a regular concern) but also on the government itself. After all, Watergate was also well underway, and the American people were less than confident in their own government — not exactly a situation that leaves the public feeling good about its economic future.

And as it turned out, they were right to be concerned. One of the lingering issues was a general shortage of raw materials, including petroleum products. Oil, in other words — an industry where the U.S. was heavily dependent on foreign imports. When the OPEC oil embargo hit a few months later, the U.S. was wildly unprepared; heavy controls were instituted on oil, setting up the infamous stories of long gas lines and odd-even rationing, and the economy tanked, leading to a severe recession that would last multiple years.