What It Was Really Like The Day Albert Einstein Died

By 1955, physicist Albert Einstein was a mega-celebrity. Indeed, he had been a major public figure since his 1919 observations of an eclipse helped bolster his theory of general relativity. Over the years, Einstein's charisma, intelligence, and growing social and political consciousness boosted his status ever further. When Einstein, who was Jewish, left his native Germany in 1932 to flee Nazi persecution, he ultimately settled in Princeton, New Jersey, at the Institute for Advanced Study. After the war, Einstein became a vocal advocate for nuclear disarmament and, near the end of his life, spent much of his time publicizing this cause.

Meanwhile, America was undergoing dramatic change, as was the rest of the world. In the U.S. of the 1950s, powerful new forms of media were on the rise, while many Americans were beginning to organize for new rights and setting the foundation for changes via the budding civil rights movement and second wave feminism. Internationally, the Cold War gripped much of the planet as the United States and the Soviet Union faced off over global control and did some pretty messed up things in the process.

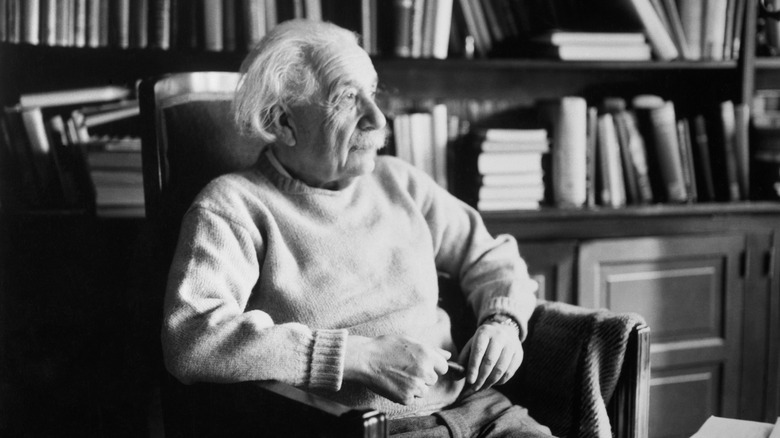

In April 1955, Einstein was still working at the Institute for Advanced Study, living in relatively humble quarters in Princeton, frequently walking to work, and generally being an affable if gently quirky neighbor. But his health was declining after years of chronic illnesses, which included digestive issues and complications caused by smoking. As would soon become clear, Einstein wasn't going to be around forever, but the rest of the world kept on turning.

Einstein died of heart failure

The truth was that Albert Einstein knew he was going to die. In April 1955, sudden pain while writing at his desk — which occurred after weeks of abdominal discomfort and fatigue – merited a diagnosis of a burst blood vessel and an internal hemorrhage. Einstein endured the pain with relative calm, even chatting with visitors and reading the newspaper. When a surgeon offered to repair the damage, Einstein refused, reportedly saying, "It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly" (via American Museum of Natural History).

More specifically, the issue was with his abdominal aorta; it had ruptured due to arteriosclerosis, the buildup of hard plaques inside blood vessels which kills off nearby cells and causes the entire blood vessel to grow weaker and more vulnerable to breaking open.

According to Helen Dukas, his secretary, Einstein found the fuss over him to be somewhat ridiculous, though he was clearly in pain and occasionally took morphine to manage the discomfort. When she set up a bed nearby, brought him ice from the home's kitchen, and generally attended to him, Einstein resisted. He eventually told her: "You're really hysterical — I have to pass on sometimes, and it doesn't really matter when" (via "An Einstein Encyclopedia"). And indeed he did pass on after finally moving to Princeton Hospital, where he died in his sleep at 1:15 a.m. on April 18, 1955, aged 76.

His remains were cremated the same day

After Einstein's death, word of the famous physicist's passing soon got out and Princeton Hospital was shortly mobbed by reporters, photographers, and curious members of the public. Despite the crowd, little information was immediately released to the public. After the autopsy had concluded, Einstein's body was taken to a funeral home in the afternoon. There, his remains were transported to nearby Trenton, New Jersey, where a presumably hastily arranged and very private funeral service was held, and his body was quickly cremated.

While some families may choose to hold on to urns containing the cremated remains of their loved ones, no such thing happened for Albert Einstein's surviving family and friends. These included sons Hans (pictured above, right) and Eduard, as well as stepdaughter Margot, whom Einstein considered to be family (another stepdaughter, Ilse, died in 1934 while a mysterious first daughter, Lieserl, disappeared from the record after 1903).

Before his death, Einstein had reportedly asked for a simple, unadorned cremation, directing that the ashes should be scattered in an undisclosed location. For Einstein, who often seemed to shy away from his very public role as a singular celebrity, the point of all this was to keep people from turning his burial site into a pilgrimage spot. Reportedly, a hospitalized Einstein also asked Margot to block any attempts to turn his home into a museum for the same reasons. This effort succeeded, as the home is currently a private residence.

One photographer managed to get unique access

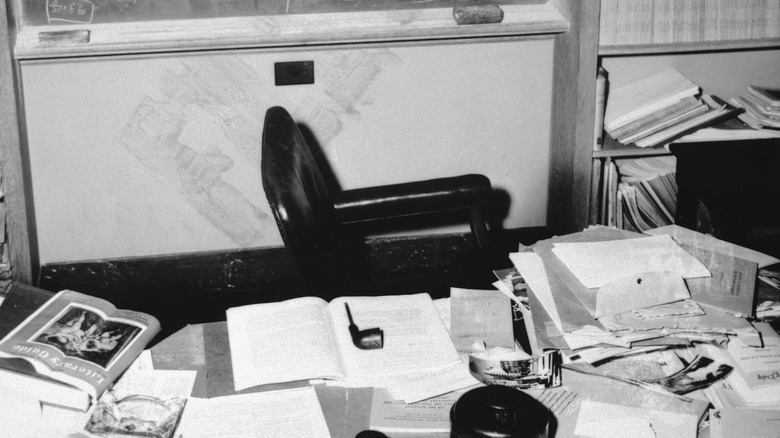

Not long after Einstein died in the early morning hours of April 18, members of the press got wind of the scientist's passing. And thought most of them naturally went to the site of his death, Princeton Hospital, to get the scoop, only one photographer managed to get unique access to Einstein's effects. That would be Ralph Morse of LIFE magazine. Having seen the hubbub at the hospital, Morse peeled off and went to Einstein's workplace: the Institute for Advanced Studies. Armed with a case of Scotch he'd bought along the way, Morse talked the building's superintendent into letting him into Einstein's office. There, Morse took pictures of Einstein's desk, crowded with papers, books, a pipe, and other ephemera, but with a now-significantly empty chair between the desk and equation-packed blackboard behind.

Not to be outdone, Morse then tracked down the location of Einstein's funeral service in Trenton, even grabbing a shot of his casket as it was loaded into the back of a hearse and a photographic portrait of pathologist Dr. Thomas Harvey (who conducted Einstein's autopsy and even removed his brain without prior permission) mid-dissection on some tissue. However, as Morse told LIFE.com, via TIME, he was pretty sure the sample in the image didn't belong to Einstein. Though he managed to take photos of the mourners both in Trenton and at Einstein's Princeton home, he apparently did not learn of or disclose just where the man's ashes had been scattered.

The United States was experiencing unprecedented prosperity

After the massive upheaval of World War II and despite the ongoing rumblings of the Cold War, Americans were feeling so optimistic about the future that they were having babies en masse in 1955, producing about 4 million babies every year throughout the 1950s. This "baby boom," as it came to be known, was in part the result of increasing optimism about the state of the world — and the United States in particular — with many seeing it as an unprecedented time of growing wealth.

The numbers certainly bore that out. By 1960, the U.S. gross national product had more than doubled what it had been at the end of World War II, ballooning to $500 billion from $200 billion in 1945. Wages were healthy while unemployment was low, and inflation likewise kept its head down. The government was improving on an interstate highway system (which grew all the more important with President Eisenhower's signing of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956), veterans were getting healthy payouts and other benefits via the G.I. Bill, and many moved to comfortable suburban homes.

However, real suburbia was no episode of "Leave it to Beaver." For instance, Black veterans didn't get the same sort of G.I. Bill benefits as white service members and faced plenty of discrimination. Looking at the dark side of the American suburbs, the Levittown, New York, suburb built for veterans was segregated and downright hostile to Black homebuyers.

The Cold War was very definitely underway

Though certain members of the American public could convince themselves that 1955 was a mighty fine year, a more clear-eyed look at geopolitics complicated things. By that year, the Cold War was an undeniable fact of international relations. Even before the end of World War II, U.S. officials had grown wary of the Communist Soviet Union. After the end of the fighting, they decided that it would be best to contain the Soviets, and support people and governments that were friendly to American-style democracy. This led to decades of tensions between the two powers, with the Space Race (and technological advances we wouldn't have without that high-flying competition), growing nuclear stockpiles, and proxy wars as just some of the results.

In 1955, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), of which the U.S. was a member, welcomed the anti-communist West Germany into the organization and allowed that state to build a military. The Soviet Union responded by creating the Warsaw Pact in May 1955, a similar group of nations committed to defending one another, which included the communist East Germany. With the ongoing crumbling of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, the Warsaw Pact lost power and was formally disbanded on July 1, 1991, while NATO remains an active political and military alliance.

Anti-war movements were on the rise

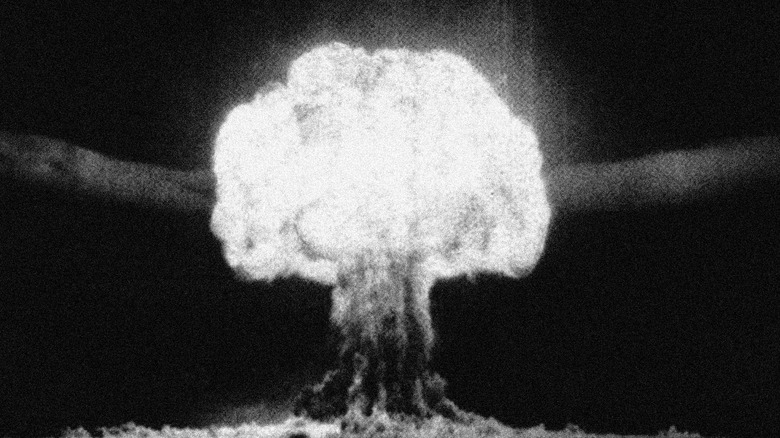

With the growth of the Cold War, fears about another world war were also on the rise. But, by 1955, anti-war movements were hardly new in the U.S., stemming back to 18th-century Loyalist colonists who opposed the American Revolution. But neither George III or George Washington had nuclear warheads at their disposal. President Eisenhower and his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Krushchev, certainly did, lending extra urgency to the anti-war and nuclear disarmament movements.

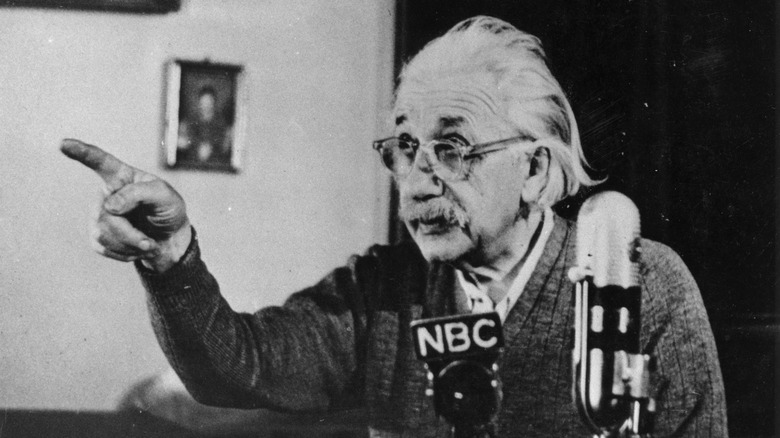

Einstein himself was a vocal proponent of nuclear disarmament, using his widespread postwar fame to argue in favor of peace. It didn't seem to do much to sway the U.S. government at the time, given how it detonated some of the largest nuclear weapons yet known in 1954 tests held at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. A Japanese fishing vessel and its crew were coated in radioactive fallout particles, as were nearby Marshall Islanders. The U.S. paid restitution to the Japanese crew the next year, but the Marshallese people didn't see any official settlements until 1988.

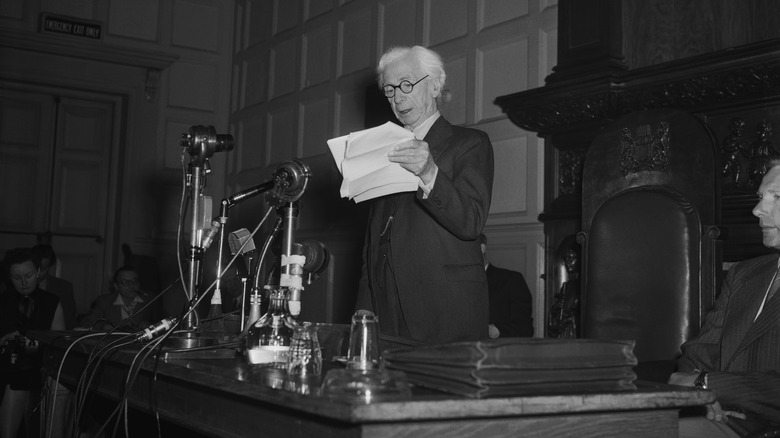

Shortly before his death, Einstein signed onto a document with philosopher Bertrand Russell, known as the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, pleading for disarmament and warning that increasingly powerful nuclear weapons could make humanity extinct. Full nuclear disarmament hasn't happened since, though if Einstein were somehow alive today, he might see some promise. That's because the U.S. has reduced its nuclear stockpile from a height of 31,255 warheads in 1967 to 3,708 today (via Nuclear Threat Initiative).

The Second Red Scare alarmed some Americans

With the rise of the Soviet Union as a major world power opposing the U.S., it's no wonder Americans began to worry about communism. By the 1950s, the U.S. had already gone through what would come to be known as the first Red Scare. In the aftermath of World War I and with the rise of the Bolsheviks (and some of the messed up things that happened during the Russian Revolution), some Americans were alarmed to see what they thought were similar movements happening on home soil.

Union organizers, anarchists, and other so-called radicals were hemmed in by the Sedition Act of 1918 and government-sanctioned raids of leftist groups. Though the fear seemed to die down by 1920, it rose again in the 1950s and became known as both the second Red Scare and McCarthyism.

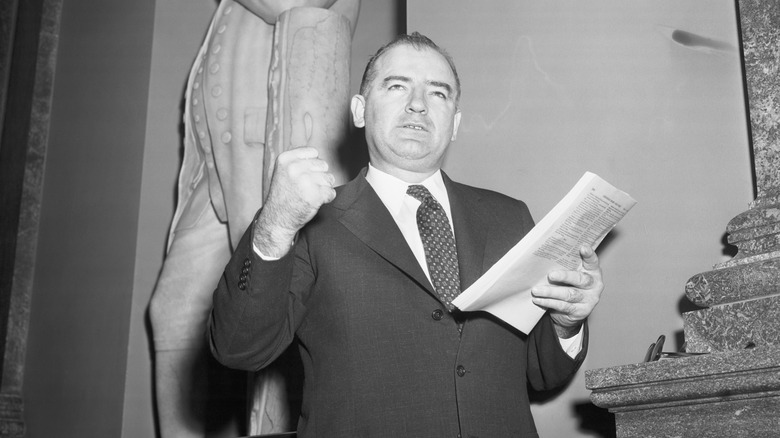

More specifically, McCarthyism (named after one of its champions, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy) targeted the perceived threat of secret American communists ... who were conveniently in league with McCarthy's political rivals. Those deemed to be "Reds" were subjected to Congressional hearings, social ostracization, a Hollywood blacklist, FBI investigations, and more. In 1954, Senator McCarthy even targeted Army officials. But, by 1955, McCarthyism was increasingly viewed with skepticism. The branch's lawyer, Joseph Welch, dealt a powerful blow to the senator's image in a televised hearing. "I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness," Welch proclaimed. "Have you no sense of decency?" (via United States Senate).

Rosa Parks was arrested later that year

Though some experienced the benefits of postwar U.S. prosperity, not everyone was so well-treated. For Black Americans, the struggle for civil rights was very much ongoing. For some, it was indeed a matter of life and death.

In August 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi, supposedly for merely whistling at a white woman. His mother, Mamie Till Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral; photos of his brutalized remains published in Jet magazine shocked many and were a significant push behind the civil rights movement.

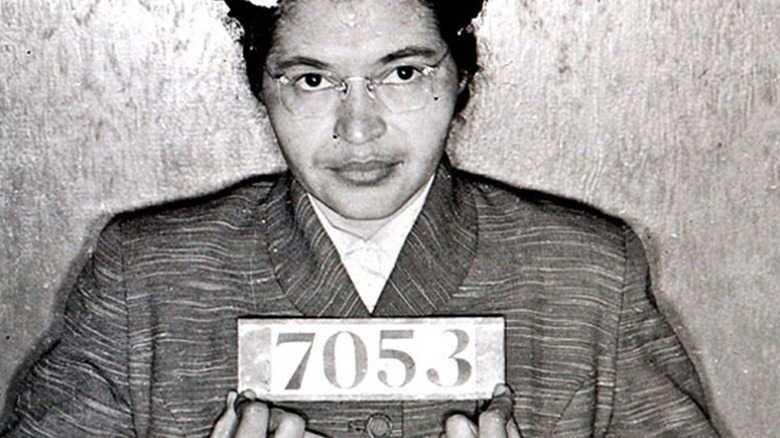

Earlier that year, in March 1955, a teenage Claudette Colvin refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama. She was arrested and briefly considered as a cause célèbre for the NAACP, but had become pregnant after her arrest. Reportedly, because the then-16-year-old Colvin wasn't married, the NAACP backed away from her case due to social mores of the time. It did take up the cause of Rosa Parks, a more obviously respectable married woman in Montgomery who also refused to give up her bus seat on December 1, 1955. Part of the untold truth of Parks was that she was already an NAACP member (she had even been her local chapter's secretary). Reaction to Parks' arrest led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which garnered national attention and fed even more fuel to the civil rights movement, as well as one of its emerging leaders: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

American women faced increasing tension

Though a cursory overview of media from the era might make it seem like the housewives of 1955 were perfectly happy with their lot, the reality was far more complex than the perfectly coiffed, tasteful, and inoffensive image that much of the mass media was attempting to present. The prevailing notion in many American communities was that women ought to marry young, have plenty of children, and stay home.

However, this idealized image was largely a fictional one. Actual women of 1955 often worked, and even those who stayed home did not necessarily tend to their housework and mothering duties with a plastered-on smile. Just two years after the first oral contraceptive pill was introduced in 1960, 1.2 million American women were using it. Clearly, not everyone was interested in the 1950s domestic ideal of a mother, which had previously spelled having three or more children.

In 1963, Betty Friedan's "The Feminine Mystique" included a blistering take on the ideals of 1950s-style womanhood. "The feminine mystique has succeeded in burying millions of American women alive," Friedan wrote, going so far as to refer to suburban homelife as "comfortable concentration camps" for those women — surely incendiary for those who viscerally remembered their time in actual World War II concentration camps. "The Feminine Mystique" is widely accepted as one of the starting points of second wave feminism, but it's clear that women's discontent with the way of things had been growing for quite some time.

The world was entering a new era of television

In 1955, one way of engaging with news and entertainment was obviously on the rise: television. By that year, an estimated 36 million television sets were in the U.S., compared to just 4.8 million in Europe. Other figures indicate dramatic growth. In 1950, a mere 9% of U.S. households had a TV. By 1960, that had changed to about 90% of households hosting their very own television set, on which consumers watched increasingly popular programs from nightly newscasts to sitcoms like "I Love Lucy" (which first aired in 1951).

But all this wasn't without a fair amount of hand-wringing. Some noted that, in places where TV usage was on the rise, consumption of other media, like books and film, started to wane. Others worried that consumers glued to the screen would become overly passive or that its influence would cause the children of America to become feral – or at least set back their education.

A 1955 assessment published in U.S. News and World Report summed up the morass of opinions, anxieties, and draws of television, noting studies that showed adult women watched the most TV, while children spent the least amount of their day in front of the screen. A year of data, ending in the month of Einstein's death in April 1955, showed that sets were on for an average of nearly five hours every day. For better or for worse, it was clear that television was there to stay.