St. Patrick: The Fifth-Century Bishop Who Became The Patron Saint Of Ireland

As saints go, once you get past the Apostles and St. Nicholas, St. Patrick is surely one of the better-known holy men, thanks to the popularity of his feast day on March 17 — when everyone assumes they're Irish for a day, drinks green beer and eats corned beef, and then engages in some combination of public nudity and public urination. And if you don't live in Ireland, there's a chance that's all you know about the guy (plus maybe something vague about snakes and shamrocks).

But the fact is that St. Patrick was a real person, a bishop who lived sometime in the fifth century A.D. and played a role in the conversion of the Irish people from paganism to Christianity. Beyond that, it's hard to divine fact from legend, but why would you want to? Dive in and learn all about the miracle-working, wizard-stomping, dragon-slaying saint whose great deeds inspire green milkshakes every year for a limited time only.

St. Patrick wasn't Irish

The first thing to understand about St. Patrick is that, while he was a historical person who really existed, most of the things we "know" about him come from much later traditions tacked on to a real person to make him sound very cool (which, to be fair, succeeded). The only things we know for sure about St. Patrick come from the two works that he wrote about his own life, known as the "Confessio" (which looks like it should mean "confession" but is something closer to "declaration") and the "Epistola," or letter, sometimes called "The Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus." The "Confessio" is basically St. Patrick's autobiography, so it's the source of most of the details we know about his life.

Despite being inextricably linked to Ireland in the public consciousness, St. Patrick was not actually Irish by birth. The young Patrick (whose birth name, according to later tradition, was Maewyn Succat) was the son of a Christian deacon in Roman Britain and was kidnapped by Irish pirates at age 16. He worked as a shepherd for six years, praying every day and asking God's forgiveness, until he heard a (presumably divine) voice telling him where to run to find the ship that would take him home and out of captivity. The bad news was that the ship was 200 miles away, but he made it and returned to Britain.

Saint Patrick was (probably) a criminal

According to the "Confessio," St. Patrick and the sailors that carried him home were starving after landing. That is, until Patrick prayed and God provided for them a whole mess of pigs that they spent two days eating. After that, Patrick devoted his life to God, until he received a letter (or, in later traditions, a mystical vision) from the people of Ireland begging him to bring Christianity to their shores. Taking this as a sign, St. Patrick returned to the Emerald Isle as a missionary rather than a slave. Not everyone was super hospitable to him.

Much of the rest of the "Confessio" and the "Epistola" deal with Patrick responding to the fact that he was on trial for mysterious (to us) reasons. It's likely, in fact, that Patrick wrote his two works while awaiting the outcome of his trial. While he never explicitly names the crimes he was accused of, he does specify that he returned gifts given to him by rich women, did not charge people for baptisms or ordinations, and paid for gifts he had given to kings and tribal chiefs (via Irish Central). Many people conclude, then, that the charges involved money trouble, particularly that Patrick had taken his position as bishop in hopes of getting that paper. And besides more details of dealing with chiefs and converting people, that is more or less all we know about the historical St. Patrick.

The legend of St. Patrick begins

Obviously, a runaway slave who returned to the place of his captivity to allegedly take bribes is an unlikely candidate to become a national hero and beloved saint. Fortunately, where fact fails, legend is often happy to make up the deficit. The first major expansion of the legend of St. Patrick came at the hands of a seventh-century monk and historian named Muirchu moccu Machtheni, who wrote a work called the "Vita sancti Patricii" ("The Life of St. Patrick"), according to the University of Nottingham. The work gave the fifth-century bishop credit for the conversion of the whole of Ireland to Christianity through various miraculous means.

In truth, Christianity probably first came to Ireland through traders and slaves from Roman Britain (like Patrick himself). There were so many Christians in Ireland by Patrick's time, in fact, that the pope had to send a Christian bishop named Palladius to tend to them all in 431 A.D. (per New Advent)

Some scholars believe that many of the traditions that attach themselves to St. Patrick were originally about Palladius, but Muirchu and other hagiographers wanted to build St. Patrick up as a Moses-like national hero in order to give a unified identity as Irish Christians to warring Irish tribes. Muirchu does this by throwing Palladius under the bus and turning Patrick into a mass-converting, miracle-working, Druid-stomping wizard for Christ. Needless to say, he was hugely successful in this regard.

St. Patrick was big time pals with an angel

One of the first things that Muirchu does to beef up St. Patrick's resume is to make him super good pals with an angel. In Patrick's own "Confessio," he talks about a man named Victoricus who was the one who brought him the letter telling him to return to Ireland (some scholars argue this Victoricus was actually St. Vitricius, a fourth-century saint from northern France, but others are not convinced).

It wasn't enough for Muirchu that Patrick had some passing acquaintance with a bishop and future saint, however. In Muirchu's "Vita," Victoricus is recast as an angel and is, in fact, the one sent by God to tell him that his ship had come in (literally). It was this same angel who then appeared to him in a vision and told him "the sons and daughters of the Wood of Focloth are calling you," which apparently meant "go to Ireland." The two spent much time together when Patrick was a slave, and the angel played a big role in Patrick's religious epiphany as well as assuring him of his eventual escape from servitude. At one point Patrick saw Victoricus leave a holy footprint on the peak of a mountain while ascending to Heaven. Later still, Victoricus appears to Patrick as a burning bush (to really drive home that Moses comparison) to warn him to change his path.

St. Patrick, wizard smasher

The bulk of Muirchu's hagiography of St. Patrick deals with Patrick's clashes with the various pagan kings of Ireland and the powerful Druid wizards they kept on retainer. (One thing that Sunday School doesn't really cover is how many wizard battles Christianity and Judaism have). Two of the most powerful Druids that Patrick encounters are Lucet Mael and Lochru, guys in the service of King Lóegaire.

After Patrick lit a fire he wasn't supposed to (long story), Lóegaire summoned him to his court to find out what this guy was all about. Once there, Patrick found himself face to face with the Druid Lochru, who provoked him by making fun of Jesus. In a move Muirchu compares to St. Peter fighting the evil wizard Simon Magus, St. Patrick uses mind powers to lift Lochru into the air and smash him onto the ground until his brain "was smashed to pieces."

Patrick's encounter with Lucet Mael is somewhat more complicated, but it involves the two men entering a miracle contest to see who can control the weather better, escalating until the challenge basically culminates in the two guys daring each other's god to set them on fire. The fact that no one dyes a river on St. Lucet Mael's Day every year should give you a pretty good idea of who won.

St. Patrick turned a guy into a fox

The rest of Muirchu's "Vita" relates all manner of miracles and hideous magical murders performed by St. Patrick, and unfortunately, there's no room to fit them all here. But if you were thinking, "Sure, he telekinetically smashed a man's head into paste and destroyed an army by summoning an earthquake, but there's no way he turned a man into a fox," well, think again.

Muirchu relates that a king named Corictic was a cruel persecutor of Christians, murdering those he found in his kingdom. When Patrick heard of this, he sent the tyrant a sternly worded letter in an attempt to get him on the straight and narrow. Corictic's reaction to this was to make fun of the letter, so Patrick prayed, asking God to do something about this rude dude. And so it turned out that at Corictic's next public appearance, a guy recited a poem about how the king was bad and should feel bad, and then everyone else started chanting about how the king sucks like it was a WWE live show. The king got so mad, he turned into a fox and ran away.

Some later versions of this story conflate this tale with the story of Saint Natalis and the Werewolves of Ossory because cursing dudes to turn into canines was a recurring theme for Irish saints.

The snakes aren't a metaphor

If you only know two things about St. Patrick as a person, they're probably that, one, he drove the snakes out of Ireland and two, something about a shamrock. You might have also noticed that neither of those incidents appeared in the — admittedly brief — survey of Muirchu's biography of Patrick above. That's because those two stories come from much later traditions, added hundreds of years after the real St. Patrick's death.

Internet access has taught most people that there haven't been any snakes in Ireland since before the last ice age, so Patrick's greatest miracle was pretty unimpressive. You might have also heard that the snakes were a metaphor for the Druids, as Patrick is credited with driving paganism out of Ireland and snakes are connected to Druids somehow. You might have even heard the sizzling hot take that St. Patrick actually committed genocide and wearing green on March 17 is basically proclaiming that you love Stalin.

Sometimes a snake is just a snake, man. The idea that the snakes were a metaphor is super recent, the addition of this story to Patrick's life is pretty late, and as you've already seen, Patrick's role in Christianizing Ireland has been pretty exaggerated (per Patheos). Plus, even a cursory glance at Muirchu shows the legend isn't shy about saying outright when Patrick kills a Druid.

St. Patrick and the shamrock

If the story of Patrick driving the snakes out of Ireland is a late addition, the almost equally famous story of the shamrock is even later, according to National Geographic. As the story goes, Patrick used the very common three-leaf clover to explain to the pagan Irish the nature of the Trinity. The same way that the clover is one thing with three separate and distinct elements, God is three-in-one, etc.

Anyway, the earliest connection between St. Patrick and shamrocks appears in 1675, well over a millennium after Patrick is supposed to have lived (per the University of Notre Dame). Likewise, written accounts of people wearing shamrocks in association with St. Patrick's Day don't appear until the 17th and 18th centuries. The earliest written account of Patrick using the shamrock to explain the Trinity doesn't pop up until 1726. In short, this story most likely arose to draw a connection between a man and a plant that by the 18th century had both become national symbols of Ireland.

Here's a bonus fact: The cute tradition of a member of the British royal family presenting the Irish Guards with sprigs of shamrocks to put in their hats on St. Patrick's Day has its origins in Queen Victoria trying to buy the loyalty of Irish soldiers so they would fight for Britain in the Boer War, one of the bloodiest wars in British history (per Vox).

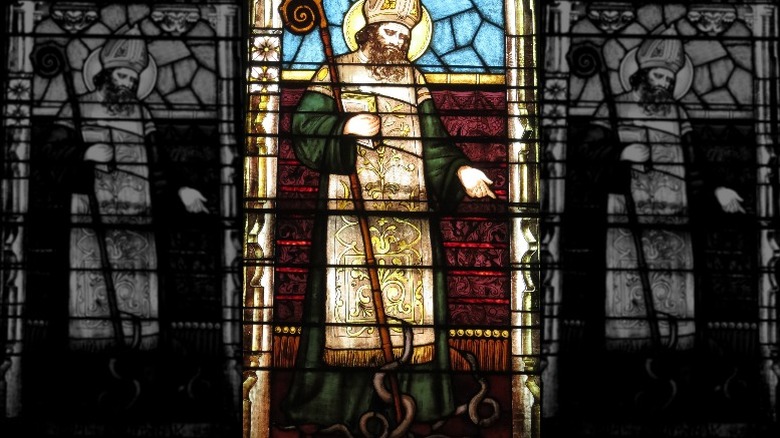

St. Patrick's color is blue, not green

The next time somebody pinches you for not wearing green on St. Patrick's Day — pinch them back. St Patrick's color should really be blue, not green. Although Ireland is known for its lovely rolling green hills, blue was the quintessential Irish color for most of Ireland's history. According to Smithsonian Magazine, St. Patrick himself used to be shown garbed in blue clothing, as was Flaitheas Éireann, the ancient personification of the island. Blue became a patriotic color for the Irish, and "St. Patrick's blue" in particular was worn by the chivalric Order of St. Patrick in the 1700s. The Irish Post points out that traces of the blue-favoring tradition can also still be seen in Irish guards' uniforms.

Nevertheless, by the Age of Enlightenment, Irish Republicanism was on the rise, along with the color green. The flag of the Irish Republic (like those of many other nations) was designed as a tricolor, a type of flag historically favored by anti-monarchical groups. Vox magazine points out that the color choice for the flag was originally rooted in religion: The green is supposed to represent Irish Catholics, while the orange stripe is for Protestants.

By the modern era, St. Patrick's blue had been largely forgotten and green was heavily incorporated into popular St. Patrick's Day celebrations, particularly in the U.S. The idea that the color green is a first line of defense against leprechauns, for example, is an uncommon, albeit charming, Irish-American myth.

St. Patrick vs. the immortal warrior

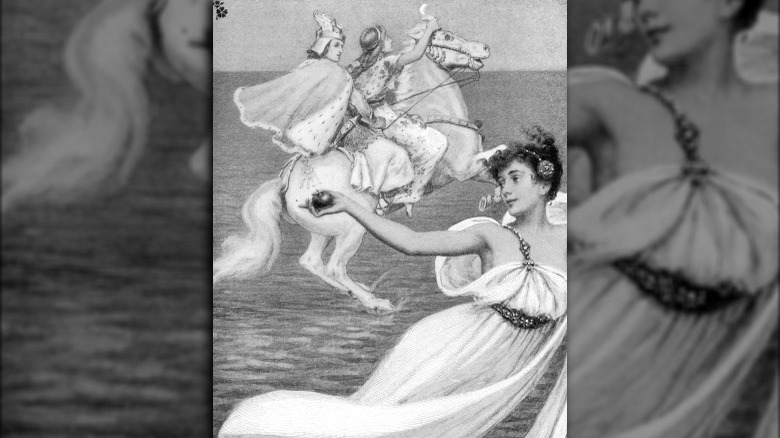

A further piece of evidence that Patrick did not wipe out all the pagans in his single lifetime is that pagan arguments against Christianity were still widespread in Ireland a thousand years after Patrick's death (per Pop Matters). But perhaps the best-known argument during the fifth century came in the form of a series of debates between St. Patrick and pagan warrior Oisin.

Oisin was the son of one of the greatest warriors of Irish myth, Fionn mac Cumhaill. Oisin managed to outlive the rest of Fionn's warriors by marrying a fairy princess who took him to the Land of the Young. When he finds out that what he thought was a few months there turned out to be 200 years, he returns to Ireland in Patrick's time to find things much changed. Instead of the warrior clans he was used to, he found priests, monks, and churches all around.

Soon, Oisin encounters Patrick, who is the only person in Ireland who recognizes the once-great Celtic warrior, and the two engage in a lengthy series of debates over the respective values of a pagan life versus a Christian one. Oisin argues that Christians are small-minded, intolerant, and mean-spirited (Patrick himself is referred to as "Patrick of the closed mind"), while Patrick condemns the violence of Oisin's way of life and extols the greatness of God. On the balance, though, Patrick (and by extension, Christianity) comes off looking pretty bad.

St. Patrick opened a Hellmouth

According to the 13th-century Golden Legend, at one point in his mission to Ireland, St. Patrick despaired that he might never get through to these crazy pagans, so he begged God to send him a sign that he was doing the right thing. God told him to draw a giant circle in the dirt with his staff; when he did so, suddenly a literal Hellmouth opened within the circle. Or more accurately, a gate to Purgatory, a waiting room where people cleanse themselves of sin. From this hole, one could hear the wailing of sinners, and Patrick was able to use this site as proof of the Christian afterlife. Stories of medieval heroes trying to enter this hole and survive are fairly common.

Here's the thing, though: This place is totally real and you can go there, according to Atlas Obscura. Well, you can't go there, like, casually, the way you might go to, say, Disneyland, but annual pilgrimages to the monastic compound built over the gate to the afterlife have continued to this day. It's on an island in the middle of a lake called Lough Derg. The pilgrimage entails adherents walking barefoot in contemplation in what is called one of the hardest pilgrimages in the Christian world. Is the Hellmouth part real? You'll have to make the trip to find out.

Basically everything in Ireland is named after St. Patrick

St. Patrick's status as the national hero of Ireland was already secured by his legend and place as one of Ireland's great patrons, but if those weren't enough, the fact that roughly 100 million places in Ireland (this may be a mild exaggeration) are named after him or his miracles will make sure you don't forget old Maewyn Succat.

Setting aside the places where his presence is obvious — like Ard Patrick, Knockpatrick, and Slieve Patrick (High Patrick, Patrick Hill, and Patrick Mountain, respectively, per Irish Central) — there are places where the connection is a little more beneath the surface. For example, the Irish townland of Saul gets its name from the Irish phrase "Sabhall Padraig," meaning "Patrick's barn," because it is the legendary site of Patrick's first church, which was in a barn (per Down Cathedral's website's website)

The Hill of Slane is where Patrick set the fire that got him in wizard trouble (per Mythical Ireland). Croagh Patrick ("Patrick's stack") is called the holiest mountain in Ireland, where Patrick fasted for Lent. Lough Derg, according to the website, is where Patrick not only opened a gate to Purgatory but also allegedly killed a sea serpent, turning the water red. Then you have Armagh, the center of much of Patrick's ministry, and Downpatrick ("Patrick's stronghold"), where he is said to have been buried, according to Ireland.com. There are also dozens of wells, islands, hills, and churches (and more churches) that bear the bishop's name.

St. Patrick's saintly status is debatable

This idea is controversial for several reasons. According to History and many other websites, St. Patrick is technically not a saint because he was never canonized. This line of thinking is a little unfair, though, because the process of canonization changed a great deal in the high Middle Ages.

In the 12th century, Pope Alexander III made up a new rule that saints had to be approved by Rome — no exceptions (via Britannica). This process evolved over time, but eventually came to involve an investigation into the holiness of the person in question, along with evidence of miracle-working. Alternatively, the pope can simply declare that an ancient saint is a saint via a tradition called "extraordinary canonization." St. Patrick was the subject of adoration long before these rules came into effect, but he never got the official nod from the popely-powers-that-be. Ergo, not a saint.

On the other hand, some may say this is nothing more than hair-splitting pedantry. Hundreds of people became saints before the 12th century and they are still treated as saints today. Furthermore, as noted by one horrified author from the Ancient Order of Hibernians, St. Patrick's relics were formerly interred at a monastery under the watchful eyes of a cardinal shortly after the rule change. This ritual was often used to identify a saintly person before a more formal process was developed, and the presence of the cardinal was effectively a form of consent from Rome.

St. Patrick's Day is more American than Irish

Outside of Ireland, St. Patrick is often primarily associated with his feast day on March 17, which has become a celebration of all things stereotypically Irish, especially in America. All the parades, green food, and alcohol poisoning is a pretty American take on the day, but that's fitting because in a lot of ways, St. Patrick's Day as we know it is much more American than Irish (per History).

While St. Patrick's Day was traditionally a day of solemnity and reflection in Ireland, America got the party started early, with the first public celebrations of the day being held in Boston in 1737 to aid needy Irish Bostonians. Soon New York got into the action with what would become the largest and longest St. Patrick's Day parade in 1762, with Irish soldiers marching through Manhattan to get breakfast.

The tradition continued in part to spite anti-Irish nativist, "America First" bozos who tried to hold their own anti-Irish shenanigans, which got outlawed in 1803. St. Patrick's Day celebrations only got a boost during the mass immigration of Irish people following the famine of 1845, with parades being held to show support for the Irish communities and show solidarity in the face of the appropriately named "Know-Nothings," another crowd of nativist idiots. So remember that St. Patrick's Day isn't just about offensive T-shirts and green beer: It also carries a legacy of spitting in bigots' eyes.