Serial Killer Mysteries That Are Still Unsolved

There's no denying that we have long been fascinated by serial killers, though they weren't identified by that term until the 1970s. Take the 16th-century German farmer Peter Stubbe (also known as Peter Stump), who allegedly confessed to killing multiple people while a werewolf, and whose story became fodder for gory illustrations and broadsides distributed amongst European readers. A century earlier, the French Gilles de Rais (who fought alongside Joan of Arc and may have inspired the legend of Bluebeard) was accused of dozens of child murders, though later historians have wondered if the charges against him were trumped up by political enemies and less-than-scrupulous tale-tellers. Either way, it's clear that serial killers have a deep and abiding hold on the human imagination. Yet, for all of that public interest, there's much we don't know about serial killers.

For one, it's still not clear what, exactly, pushes someone to be a serial killer, though the current consensus among mental and behavioral health experts is that it's likely a combination of biology, injury, and environment that can lead someone down that path. Go a little deeper into individual cases, and you'll find many more lingering questions, from the identity of those who committed a spate of crimes to mysteries about exact numbers and identities of victims. Some may be solved given enough time and investigative technology, while other mysteries could remain unsolved for much longer yet.

Who was the Servant Girl Annihilator?

It began on the last day of 1884 in Austin, Texas. Mollie Smith, a Black woman who worked as a cook, was in bed when she was first stabbed, then pulled outside and killed with an ax. Another working-class servant was killed in much the same fashion half a year later. Eventually, as six people — all from Austin's Black community — were brutally killed with hand implements, people began to frantically look for a killer on the loose. They deemed the shadowy figure the Servant Girl Annihilator.

Because the murderer initially seemed to target Black people, white Austinites initially decided that it wasn't their problem. Then, on December 24, 1885, two white women were killed. At that point, public fear had already been rising and was made all the more tense with the realization that anyone could be targeted. Police charged the respective husbands of the women, but nothing came of it and the men were released.

At that point, the attacks seemed to stop. Had the killer died? Moved away? No one knew. Some have since claimed that the Servant Girl Annihilator was none other than the future Jack the Ripper, meaning the potentially Texan killer moved across the Atlantic Ocean and blended in well enough in London's East End that he was never caught there, either. Others pointed to more local petty criminals, but no one was ever definitively identified as the killer.

Who was Jack the Ripper?

Though he certainly wasn't the first known serial killer in history, Jack the Ripper is one of the most notorious. He holds our interest more than a century after the deaths of five confirmed victims in 1888 London: Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. Others have claimed the same killer was responsible for more murders as late as 1892. Yet we still don't know who he was despite well over a century of media attention.

Speculation has run so rampant that more casual onlookers might be forgiven for thinking that everyone in 1888 London was a suspect, from a local midwife to Queen Victoria (or at least her wayward grandson Eddy). More recently, genetic analysis of samples from a shawl found with Eddowes pointed to barber Aaron Kosminski. Yet not everyone was convinced, saying the mitochondrial DNA retrieved is only good for excluding people, not identifying a long-dead serial killer. Others say it's hard to confirm that the shawl was really at the crime scene or that it hadn't been contaminated.

More recent evidence is just as shaky, including a cane owned by detective Frederick Abberline that supposedly sports an image of the killer created from eyewitness accounts. But that's hardly a smoking gun and, as far as many are concerned, we're no closer to definitively identifying Jack the Ripper than in the 19th century.

Not all of Ted Bundy's victims have been recovered

Though Ted Bundy confessed to killing 30 women during a nationwide spate of murders in the 1970s, the exact number of his victims remains in doubt. Some investigators have guessed that his victims may be more accurately counted at over 100, pointing to the oddly efficient brutality of his 1970s crimes as evidence that he may have started earlier than many once thought. Bundy was executed by the state of Florida in 1989, meaning investigators can't mine any more information from what was a potentially unreliable, but at least first-hand, source.

Many consider it likely that there are still unrecovered remains of Bundy's victims out there. In March 2024, Utah private investigator Jason Jensen told Cowboy State Daily that he intended to search for four of those women during the summer of 2024, assisted by his human remains detection dog. Jensen is focusing on four missing women — Debra Kent, Nancy Wilcox, Susan Curtis, and Julie Cunningham — because Bundy directly confessed to their murders shortly before his death.

Though investigators dropped the ball on extracting more information about their burial sites, at least according to Jensen's assessment, he holds what he believes to be a reasonable hope of finding remains and perhaps bringing closure to the women's families. Kent's kneecap, confirmed to be hers via genetic testing, was even recovered in the remote area of Utah where Jensen plans to search first (Cunningham is reportedly buried in western Colorado).

Could the Monster of Florence have been part of high society?

Between 1968 and 1985, a serial murderer dubbed the Monster of Florence took at least 16 victims. Some investigators alleged that the Monster was actually a group of serial murderers working in concert. Whoever it was had a fairly consistent modus operandi, killing eight couples in the hills outside of town and reserving particular brutality for female victims.

Originally, Pietro Pacciani was convicted of killing 14 of the victims in 1994. Then, his conviction was overturned. He was set for a new trial, but died in 1998 before proceedings could begin. Shortly before Pacciani's death, two of his associates were also convicted of participating in the murders.

Yet some argued that Pacciani's case had odd details, like the fact that an illiterate laborer had managed to buy two houses and had a rather hefty £50,000 in the bank. And was one of Pacciani's convicted associates, Giancarlo Lotti, telling the truth when he said a doctor had directed them to kill? Or, was he spinning a wild tale to take some of the blame off his shoulders? Some detectives then spun their own story of a shadowy occult group made up of high-ranking citizens of Florence or maybe a top-secret Italian government agency. Little came of those suspicions over the years, but author Thomas Harris attended some of the first court hearings and took the notion to the page, inspiring the creation of fictional upper-class serial killer Hannibal Lecter.

BTK may have committed more crimes

Dennis Rader spent nearly 20 years terrorizing the area of Wichita, Kansas, killing 10 people between 1974 and 1991. He was finally apprehended in February 2005, after a newspaper article speculating that the then-unidentified serial killer — who had deemed himself BTK for bind, torture, and kill — had died pushed the publicity-hungry Rader into contacting police again. Investigators received a floppy disk from the killer and traced data on the media to Rader.

Though Rader pleaded guilty to 10 counts of murder at his 2005 trial, some have long suspected that this is not a full accounting of his crimes. Indeed, law enforcement claims that there's credible evidence connecting him to at least one other missing person: the 1976 disappearance of Cynthia Kinney in Oklahoma. In 2023, Osage County Undersheriff Gary Upton told NBC News that it's possible Rader may have killed even more people, given that he was active for some 30 years at least.

Investigators were assisted by an especially close source: Rader's daughter, Kerri Rawson, who interviewed her father in prison and used her own memories to pinpoint key details and sites that warrant further investigation. These places include Rader's former home in Park City, Kansas, where a 2023 search conducted by the Osage County Sheriff's Office uncovered unspecified "items of interest," according to a press release issued by the office.

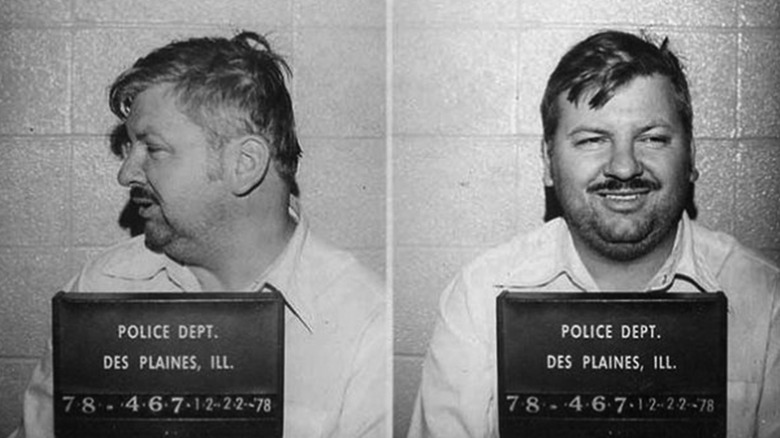

Did John Wayne Gacy have an accomplice?

In popular imagination, serial killers are often shown as singular figures committing their heinous acts in isolation. But that may not be the case for all. Some, like the Houston-based Dean Corll, received help from accomplices. Could other killers also have had help?

That's long been the speculation for John Wayne Gacy, the serial killer who murdered an estimated 33 boys and young men largely around suburban Chicago in the 1970s. After Gacy was arrested in the late 1970s, police found that his home in Norwood Park, Illinois, contained the remains of 29 victims, with at least four more deposited in the nearby Des Plaines River. Some have claimed that the timelines of when those victims went missing and when Gacy was in town don't always line up, leading them to conclude that Gacy must have had at least one accomplice who was never apprehended. Gacy has said as much himself, yet serial killers aren't always known to be reliable, especially when they're courting notoriety or attempting to avoid the death penalty. However, if that was Gacy's motivation, the tactic didn't work exceptionally, as he was executed in 1994.

Not everyone is convinced. Retired Des Plaines police officer Michael Albrecht, who witnessed Gacy's confession, told Esquire that he believed Gacy was a meticulous killer who worked alone. Some of Gacy's associates may have begun to suspect something strange was happening, but he maintains there's no evidence anyone was actively helping Gacy to kill.

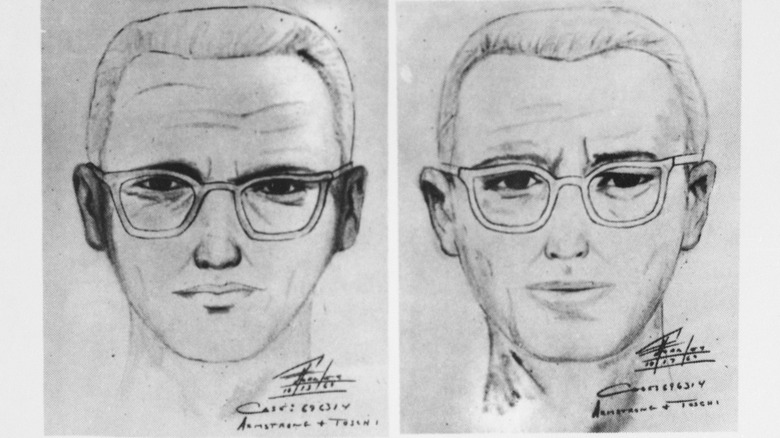

We still don't know much about the Zodiac Killer

The bare bones of the case are as such: the Zodiac Killer was active around San Francisco in the 1960s, murdering five confirmed people during attacks on couples at remote locations and one taxi driver. Survivors and other witnesses described a man, sometimes seen wearing a hood and shirt bearing the symbol of a cross within a circle, who tied victims up and stabbed or shot them. Despite a police sketch and contact from the alleged killer himself (including a phone call to the Vallejo Police Department and letters written in cipher and sent to local papers), no one has definitively identified the Zodiac Killer. Even when cryptographers cracked the cipher in 2024, the boastful, taunting contents revealed little about the killer's identity.

Some have pinned the crimes on relative unknowns such as Arthur Leigh Allen and Earl Van Best Jr., while others named more notorious figures, including the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, and even cult leader Charles Manson. Others have guessed that the one-killer theory is all wrong, noting that the details connecting the different killings (such as victims targeted and weapons used) could be distinct enough that they were committed by totally different people.

It's not even clear how many people were harmed by the Zodiac Killer. Some have linked earlier and later deaths to the figure, based on similar patterns and geographic proximity, such as the shooting deaths of Robert Domingos and Linda Edwards in 1963 near Santa Barbara.

Why couldn't the police find Bible John?

By October 31, 1969, three women — Patricia Docker, Jemima MacDonald, and Helen Puttock — had been found murdered in Glasgow, Scotland. All had visited the Barrowland Ballroom the nights of their deaths, were killed in a similar manner, left near their homes, and had been menstruating at the time of their deaths. Puttock's sister, Jean, was even with her sister the night of her death and rode in a taxi with Helen and an unidentified man while leaving the Barrowland. Jean was dropped off and Helen continued on with the man, who was the last known person with her while she was alive. Jean told police that he called himself John and quoted from the Bible, giving a physical description.

Though she quite possibly shared a cab with the killer, little came of Jean's testimony. Some suggested that the police actually knew who Bible John was all along, keeping things covered up because he was allegedly related to police detective Jimmy McInnes. That suspect, John Irvine McInnes, died by suicide in 1980. His remains were exhumed in the 1990s for DNA testing, but he wasn't a match for samples found on Helen Puttock's tights.

Others wondered if the culprit was an already-known serial killer, Peter Tobin, who murdered people as late as 2006 and who died in 2022 while serving three life sentences. Yet, the lack of evidence for the Tobin theory or any others means that Bible John's identity remains obscured.

Are there missing victims of Dean Corll?

In the early 1970s, a shocking number of young men went missing in and around Houston, Texas. It only stopped in August 1973, when a man named Dean Corll was shot to death in his home by 17-year-old Elmer Wayne Henley. A search of Corll's home and property found the remains of some 27 missing boys and men, including individuals as young as 13. Henley, along with 18-year-old David Brooks, had been one of Corll's assistants, helping to kidnap, torture, and kill the older man's victims. Corll — later known as the Candy Man killer — reportedly threatened to kill Henley and his friends, prompting his murder.

Nearly all the victims have been identified, with the exception of one 15 to 18-year-old boy who died around 1972 and is currently referred to as John Houston Doe. In 1983, a 28th victim was uncovered (and later identified in 2009). When interviewed, Henley maintained that there were even more victims out there, perhaps 20 or more. Investigators agreed, but searches have turned up little evidence, even when the property of Corrl's final home was excavated.

Further complicating matters is the fact that many missing boys and young men from that era were dismissed as runaways by police, who did not necessarily devote much effort to tracking down people they assumed did not wish to be found. Many decades later, families are left wondering if their missing loved ones may have been a victim of Corll.

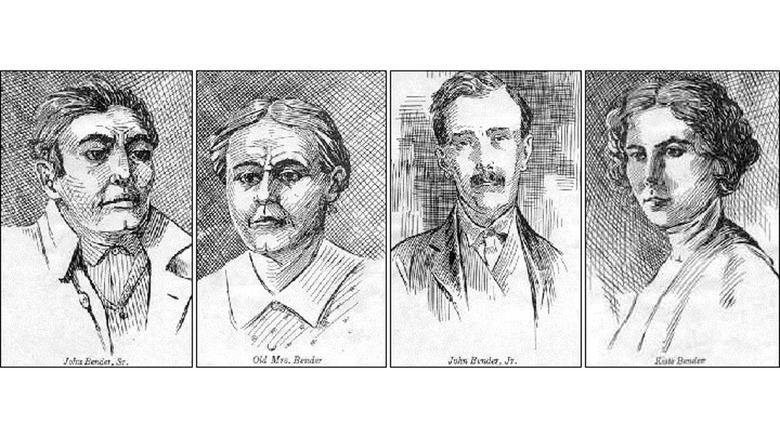

Where did the Bloody Benders go?

For serial killer mysteries, it's hard to find a story with more unanswered questions than that of the Bloody Bender family. Though there's little question they really operated in the hinterlands of 1870s Kansas, preying on travelers on the nearby Osage Trail, little else is known about them.

The group consisted of the unfriendly Pa and Ma Bender, who spoke little English. Their children were the adult John (reported to be a friendly if odd man who giggled at strange times) and Kate. Not long after they set up their homestead near Cherryvale, Kansas, travelers began missing. Interest didn't really circle around the Benders until the disappearance of William York, whose politically ambitious brother Alexander put together a search party. After the party questioned the Benders, the family — if they ever were a family in the first place — skipped town. A search of their property found a small graveyard of sorts that contained William's body, as well as those of 10 other people.

But where did the Benders go? The subsequent roll of sensationalist news coverage and faulty memories didn't help things. Various accounts said they were apprehended and killed by local vigilantes, split up, or boarded a train to Texas and then traveled further into the lawless Indian Territory. Famously, one late 19th-century incident had two women tried for being Ma and Kate, but the lack of evidence (and the women's propensity for telling lies) meant the case was eventually dropped.