The Untold Truth Of St. Nicholas

Saying the name "St. Nicholas" in America will almost undoubtedly conjure up images of Santa Claus, the jolly Christmastime gift-bringer known for flying around the world on Christmas Eve to deliver presents to the good children of the world. But long before he gave his name to this beloved holiday icon, St. Nicholas was a real historical person who became so beloved that an enormous body of legend came to surround him. Originally, however, he had nothing to do with Christmas.

And completely outside his connection to Santa Claus, St. Nicholas is enormously popular across the world. He is the most popular non-Apostle saint, and he is invoked as the protector of children, sailors, merchants, thieves, pharmacists, the falsely accused, Russia, Greece, and many more. And the reason for that is not because of Santa Claus. It's because the traditional St. Nicholas was a wonder-working, child-resurrecting, demon-taming, shrine-smashing, heretic-punching, astral-projecting, gift-giving man of action. If any of that is a surprise to you, here's the truth about St. Nicholas.

St. Nicholas was holy from Day One

Nicholas didn't waste any time getting holy. He was born in Patara in what is now Turkey in the third century (on March 15, if you've ever wondered when Santa's birthday is) to Christians named either Theophanes and Nonna or Epiphanes and Joanna. According to legend, after his first bath, the infant Nicholas stood up in the tub and praised God. He would also abstain from his mother's milk on fast days. He avoided the typical naughty behavior of young boys and attended church frequently.

The young Nicholas spent much of his time studying with his uncle Nicholas, his namesake, who was the abbot at a nearby monastery in Xanthos. He performed his first miracle while walking to one of his lessons as a young boy when he came across a woman with a withered hand and healed it by making the sign of the cross over it. His parents died of the plague when Nicholas was still a young man, leaving him a sizeable inheritance (presumably related to shipping, as Nicholas has long been associated with sailors). He lived with his uncle the abbot and followed his example by making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, where the locked doors of the Room of the Last Supper on Mount Zion miraculously swung open to greet him when he went there to pray.

What's in a name?

By most accounts, the name Nicholas is derived from the Greek words nike, meaning "victory" (yes, like the shoe), and laos, meaning "people." Combined, the name means "victory for the people"; according to the Golden Legend, he was called this because through his teaching and example, he brought a great victory to the people over their sins and vices. The name was an uncommon one at the time Nicholas got his name, and pretty much anyone named Nicholas now is ultimately due to the famous saint.

The rarity of his name played a role in his becoming the bishop of Myra, a city elsewhere in modern-day Turkey. The previous bishop of Myra had died, and the other bishops of the area were having a hard time deciding on a successor. That night, the voice of God came to the eldest bishop and told him they should name as bishop the first person to come into the church in Myra whose name was Nicholas. Honestly, God could have just said the first person to come in the church, period, because that was our boy Nicholas, as he was traveling back home from the Holy Land. When he (or in some versions, a sailor traveling with him) revealed his name to the bishop, he was immediately made the bishop of Myra, despite his modest protests.

St. Nicholas, giver of gifts and protector of sex workers

If you only know one story about Nicholas of Myra, it's probably the one that led to him being known as a giver of gifts and also as the patron saint and protector of both sex workers and pawnbrokers. As the story goes, one of Nicholas' neighbors was a man who had once been rich but had fallen on hard times. He didn't have enough money to afford the dowries for his three daughters, and he was legitimately concerned he would have to sell them off into the kind of slavery that young girls would have been sold off into in those days.

Enter Nicholas, who has heard of his neighbor's plight and is heavy laden with inherited wealth from his parents. Wanting to help his neighbor but not wanting credit for it, he snuck through the night and threw three bags of gold into his neighbor's house so the girls could get married. (In more modern versions of the story, he is usually said to have thrown it through the chimney in order to tie it to the Santa Claus story, but chimneys didn't exist in the third century, so it was probably through the window. Some versions also add that the gold fell in the girls' drying stockings.) St. Nicholas is often depicted holding three bags of gold, sometimes abstracted as three gold balls, which are still the symbol of many pawn shops.

St. Nicholas, friend of children and bane of cannibals

Even long before he was transformed into Santa Claus, jolly old Saint Nicholas was known as the children's friend. Among his many patronages, perhaps the most famous is his role as the protector of children, an aspect that stems from another of his most famous miracles.

According to legend, three young students were traveling on their way to school and were looking for a place to spend the night. They find an inn run by a butcher and his wife, who sees the boys' fat wallets and gets some bad ideas. While the boys sleep, the butcher kills them, chops them up, and puts their disassembled bodies in a pickling barrel. Before they know it, however, there comes another knock at their door. This time they're greeted by a regal-looking bishop who demands fresh meat for dinner. When the butcher replies he doesn't have any fresh meat, St. Nicholas insists he has the freshest meat of all and demands he open his pickling tub. Nicholas prays over the tub, and instead of loose body parts spilling over the floor, three whole, fully alive boys come out, who give thanks to Nicholas and God and then make their way home. In France, it is said that Nicholas subsequently put the butcher in chains and forced him into servitude to make penance for his crime, but more on that a little later.

Nicholas saves sailors while napping

St. Nicholas is associated with a number of stories about sailors, ultimately leading to his becoming the patron of sailors as one of his main things. One such story involves him resurrecting a sailor from the dead who died during a storm on his trip to the Holy Land, but the more impressive feat involves Nicholas saving a shipload of dudes without even being physically present.

At the famous and actually completely historical Council of Nicea, Nicholas fell asleep during dinner. In a dream, he heard voices calling his name for help. So without even waking up, Nicholas astral-projected like Dr. Strange, leaving his physical body behind and sending his spirit hundreds of miles away to the middle of the sea where he found a bunch of sailors struggling to stay afloat after a storm had wrecked their ship. Nicholas spread his ghost hands over the water and calmed the sea, saving the lives of the grateful sailors before astral-projecting back to his body, which was probably face-down asleep in a pile of larks' tongues or whatever they were eating.

When the other bishops were like, "Hey, man, where'd you go?" Nicholas replied, "A ship and all its sailors were saved." They took this as a metaphor in which the church was the ship and the sailors its parishioners, and so they all nodded like, "This Nicholas dude is very deep."

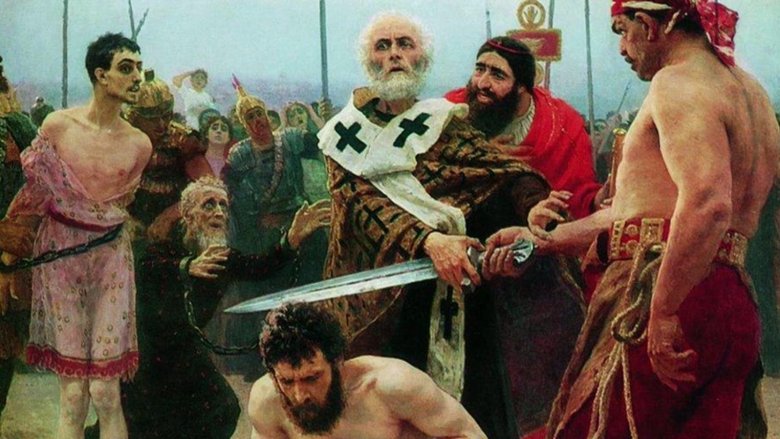

St. Nicholas socks a heretic

The most famous event involving St. Nicholas at the Council of Nicea was something of a scandal for our boy. This council, which was convened in 325 A.D. by the Roman emperor Constantine, was the first ecumenical council (meaning that it pertained to the whole church and not just a regional issue) and primarily dealt with the Arian heresy. The Arian heresy had nothing to do with the similarly-named Aryan race, but rather the teachings of a man named Arius, who said that Jesus was made by God, not begotten by him. To a modern audience, this seems like a pretty minute distinction, but to the early church, this was full-on crisis-mode important. Arianism was surprisingly popular in fourth-century Europe, and the orthodox church felt pretty threatened by it.

So threatened, in fact, that as Arius stood on the council floor defending himself, our boy Nicholas strode across the room and slugged him. It turns out it's illegal to assault anyone, even a heretic, in front of the emperor, so Nicholas was stripped of his position as bishop and put in jail. Fortunately, that night Mary and the baby Jesus came and freed Nicholas from his chains and returned his episcopal garments, forcing Constantine to reinstate him as bishop of Myra and presumably give him mad props for having the baby Jesus as a character reference.

St. Nicholas versus Artemis

As should be clear from their interaction, the lives of St. Nicholas and the emperor Constantine, who made Christianity legal in the Roman Empire, overlapped. This meant that St. Nicholas lived during a time when Christianity was illegal, even being imprisoned himself during the persecutions of the emperor Diocletian, and the polytheistic state religion of the Romans was the status quo in most of the empire. In the area where St. Nicholas lived, the goddess Artemis was the primary deity, worshiped as a daughter of Zeus and a powerful virgin fertility goddess. Since Artemis was the main pagan goddess on Nicholas' home turf, there are a number of stories of the two of them clashing.

St. Nicholas would travel the land, seeking out shrines and temples to Artemis and destroying them, driving out the demons or fauns or satyrs within. This culminated with Nicholas using mental powers to lift up the enormous temple of Artemis in Myra from its very foundations, flipping it, and smashing it to pieces on the ground, sending demons scattering to the wind. Artemis would later try to get revenge by disguising herself and giving pilgrims to Nicholas' shrine a jar full of what she said was oil to anoint the shrine, but which basically turned out to be a bomb. Fortunately, the ghost of Nicholas appeared in time and saved everyone.

Even more miracles of St. Nicholas

St. Nicholas, as an extraordinarily popular saint, has no shortage of miracles attributed to him. After the most famous ones, perhaps the most prominent B-miracle is the story of how he saved his home from famine by miraculous means. The people of Myra were starving, and some merchant ships from Italy stopped there on its way to deliver grain to Egypt. When St. Nicholas offered to buy some of the grain, the captain refused, saying he would be punished for any shortage. St. Nicholas assured them it would be fine and bought a hundred bushels from each ship. The merchants were relieved to find that the exact right amount was still aboard the ship when they arrived in Egypt, and the people of Myra had enough to eat for two years.

Other stories show him saving falsely accused soldiers from execution by catching a sword blade in his bare hand, magically saving a young boy from slavery, and saving a boy from drowning whose father had tried to steal a gold cup from God. The Golden Legend even has a few stories about St. Nicholas avenging Jews who were abused by anti-Semites. And for all the stories during Nicholas' lifetime, he has an almost equal number of posthumous miracles protecting those who prayed at his shrines and punishing those who abuse them, even possessing a statue of himself to beat a thief in a footrace.

Grave robbing for fun and profit

Of all the great and supernatural miracles attributed to St. Nicholas, perhaps the most surprising feat he pulled off was dying of old age. Many saints, including all but one of the Twelve Apostles, are known for the usually pretty gruesome ways in which they were martyred, but old Saint Nick managed to die peacefully, borne aloft by angels, in 343 A.D.

His body was placed in the crypt of the cathedral in Myra, and all was cool until the Seljuks took over much of Turkey in the 11th century. Nicholas' tomb was a common pilgrimage destination, especially since his tomb was said to produce mana, a liquid with healing properties. Wanting to save the body of the saint from the conquering Seljuks (and to bring glory to their own hometown), 47 sailors from the Italian city of Bari went down to Myra in the year 1087 to recover the body of St. Nicholas. The sailors lied to the monks who guarded the body in order to gain access to it, but a number of miracles convinced them they were doing the right thing. When they uncovered the body, the smell of perfume filled the town, positively identifying the saint. The sailors took the body back to Bari, where it still lies today. This act is still celebrated as the Translation of the Relics and is the reason St. Nicholas is the patron saint of thieves.

Saint Nicholas isn't Santa Claus

While in mainstream American culture, St. Nicholas is almost entirely conflated with Santa Claus, the fact is that they aren't exactly the same, and in many parts of the world — and by some people even in the U.S. — St. Nicholas Day, which is on December 6, is celebrated completely separately from Christmas, and some of them are fiercely opposed to the creeping Americanism of Santa Claus. (There's a whole history of how the gift-giving aspects of St. Nicholas Day got transferred to Christmas during the Protestant Reformation, but that's more than there's time for here.)

No country celebrates St. Nicholas Day quite like the Netherlands, where Sinterklaas is a much bigger affair than Christmas, which includes the saint arriving by steamboat from Spain with his companion Piet (more on that in a minute), throwing out spice cookies and riding a white horse. In other regions, St. Nicholas might ride a donkey rather than a horse, or climb down from heaven on a golden rope, or come accompanied with completely different companions, but almost universally in places where Saint Nicholas comes, children set out their shoes on the night of December 5 hoping the Children's Friend will fill them with candy, fruit, nuts, toys, and treats. Bad children get pieces of coal, an idea familiar to American children, or maybe a potato, which would be less familiar.

St. Nicholas, demon tamer

His reputation as a miracle worker gained him the name Nicholas the Wonder-Worker, but St. Nicholas was also known in legend for taming demons. In one story he might banish demons from a tree by threatening them with an ax, in another he's resurrecting a boy strangled by a demon, and in yet another he's outsmarting a demon in a wager. In many of these traditions, St. Nicholas ends up impressing the demons into his service, earning penance by helping the saint in his saintly duties. This tradition plays into the concept of the dark companion of St. Nicholas, chained monsters who play bad cop to the saint's good cop.

The most famous of these is, of course, the Krampus, who has gained considerable cultural cachet in the last decade thanks to appearances in movies and TV shows, which aren't a great representation of the actual traditions of Austria and Germany. The Krampus isn't the only shaggy, horned accomplice of the saint, though, as other regions await the arrival of the Klaubauf, Bartel, or Pelzebock. In the Czech Republic, St. Nicholas is accompanied by an angel and a devil, while in other places he gets a more human, if usually dirty, companion. These include Schmutzli in Switzerland, Hans Trapp in the East of France, and Pere Fouettard — said to be the butcher who killed those three boys — in Northern France.

Other companions of St. Nicholas

While St. Nicholas' evil companions have gotten the most attention in pop culture in recent years, he also has a number of not-so-evil companions who maybe once played that scary bad cop role that have softened over time, becoming something more like a helper than spooky muscle. (Although to be fair, the real-life portrayal of some of the still-kind-of-scary ones have generally softened over the years as well.)

Possibly the most beloved and arguably the most hated of St. Nicholas' companions is Zwarte Piet, or Black Peter, who accompanies Sinterklaas in the Netherlands. The character in a form recognizable today goes back at least to the 19th century, but his popularity greatly expanded after World War II when Allied troops tried to cheer up Dutch children by saying maybe there should be a whole crowd of Black Peters instead of just one. Anyway, a pretty considerable controversy over the character has arisen in recent years due to the fact that he is almost always portrayed by a white person in blackface (again, an issue there's not room for here).

A less controversial companion is Knecht Ruprecht, or Farmhand Rupert, another German figure, who wears a monk's robes and a long beard, rewarding children who can recite a song, poem, or prayer with small gifts, and giving a small whap with a bag of ashes or just a piece of coal to those who can't.