Yakuza: The Truth Behind Japan's Massive Crime Syndicate

Plenty of countries have organized crime syndicates. There's the Italian Mafia, the Russian mob, the Latin American drug cartels — even the ever-so polite Canadians have a flourishing underworld. But perhaps none of them have the same aura of mystery and fear as the infamous Japanese yakuza. If you run into a guy covered in tattoos and missing half his pinky finger, it might be a bad idea to piss him off.

But what is the yakuza's deal exactly? How did the whole gangster things start? What are they getting up to these days? And wait, why do they voluntarily chop off their pinkies because that is completely crazy? It turns out the yakuza is a complicated organization with rich history and traditions that manages to fit in lots of charity work in between murdering bunches of people. Like all villains, they are more than just pure evil, although there is definitely plenty of evil to go around.

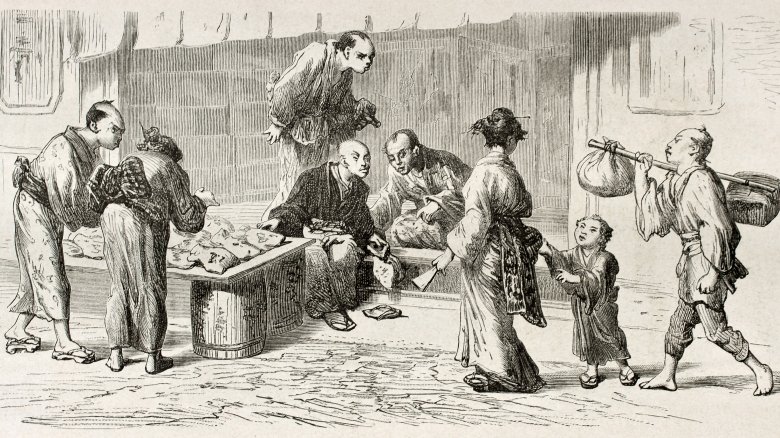

The yakuza started as outsiders spit on by society

The yakuza's origins are older than you might think. In the early 1700s, outcasts in Japan began organizing into groups. The idea was that one outcast might be treated like trash but if you have a bunch of outcasts who have each other's backs and are willing to do illegal, sometimes violent things to protect members of the group, suddenly they don't get treated so badly by the general populace anymore.

According to ThoughtCo, some outcasts were tekiya, basically traveling salesmen who hawked cheap goods at festivals and markets. They were considered the lowest of the low, members of the burakumin social class, which means they were "non-humans." They formed hierarchical groups and started running protection rackets and participating in turf wars. Things got so bad the government tried to legitimize the tekiya a little bit. The big boss of each group was officially sanctioned and given the title oyabun, plus allowed to use a surname and carry a sword, things only samurai were normally permitted.

The other group of outcasts who organized were the bakuto — gamblers. Gambling was (and still is) illegal in Japan. The guys who fleeced unsuspecting marks were already breaking the law, so it made sense when they started doing other illegal stuff like loan sharking. Modern-day yakuza grew directly out of these earlier organizations. They still use the same naming conventions, along with many rituals that began centuries earlier, and their colorful full-body tattoos are also a throwback to the old ways.

The yakuza has a mostly legal side

You'd think that the Japanese view on the yakuza would be cut and dry: They're bad guys, right? But it's a lot more complicated than that. Encyclopedia Britannica says some Japanese people see the yakuza as a "necessary evil." The idea is that the organized and controlling nature of the group acts as a "deterrent to impulsive individual street crime." In other words, in a crazy, twisted way, the yakuza help keep the Japanese crime rate low. The yakuza make some of their money in the stereotypical manner of criminals: prostitution, blackmail, gambling, and the like. But their real wealth comes from completely legitimate businesses, which are often clearly marked as being yakuza owned.

That's because the yakuza is, technically, not illegal. While Japan has brought in stricter laws against organized crime in the 21st century, just existing is not a legitimate reason for police to do anything. In fact, the relationship between law enforcement and the yakuza is "a complicated one." The cops know which businesses are mobbed up and they know about gang activities that are happening, but despite this they often don't do anything about it. The yakuza are so good at staying just this side of legal that it's hard to justify arresting them for lesser or white-collar crimes, so they usually get away with them.

One recent development is regular citizens suing the yakuza to get back protection money they've paid. It's working and could be a creative way of making criminals' lives harder.

Then there's the mudery side of the yakuza

It is not accurate to say that the yakuza stick entirely to white collar crime and moderately legitimate businesses, though. They are feared for a reason: a lot of dead bodies. According to the Daily Beast, gangland murders are a kind of circle of death. One family sets up a hit on a member of a rival family, then that leads to another murder, and another, in a neverending cycle of violence. The Guardian reports mob murders can also lead to turf wars and numerous shootings all at once, which is notable in a country where gun violence is extremely uncommon.

But the yakuza don't just kill each other. Any regular civilian who crosses them could be in danger. Examples include Igari Toshiro, a leading lawyer in the anti-organized crime movement in Japan, who was found dead in 2010. While it was ruled a suicide, many think the yakuza staged it. Kunihiro Kajiwara, head of a fishermen's cooperative, was gunned down in 1998, allegedly for not giving a construction contract to a yakuza company. Real estate consultant Kazuoki Nozaki was stabbed to death in 2006 for his involvement in a disagreement over a building a yakuza company wanted to own. And the mayor of Nagasaki was killed by a gangster angry about a ding his car got four years earlier.

Before 2010, crimes had a 25-year statute of limitations in Japan. This meant if a yakuza hid for long enough, he could quite literally get away with murder.

The yakuza has a cozy relationship with some politicians

The yakuza as a group are ultra-nationalist right-wingers. The Christian Science Monitor reports they often even "formally register with the government as right-wing political groups." This makes their more-than-cozy relationship with conservative politicians concerning to a lot of people. With two brief exceptions, the Liberal-Democratic Party has been in charge of the Japanese government since 1955. Despite their name, they're a conservative political party. And there are plenty of examples of them working with mobsters.

Tanaka Kakuei was prime minister in the 1970s. According to Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld, in 1983, two of his campaigners were arrested and revealed to be members of the yakuza family in the district he represented. He wasn't the only one to do something like that; politicians seem think the yakuza are great at campaigning and fundraising. But sometimes gangsters will be recruited by politicians for purely personal reasons, like when they use them to intimidate annoying family members. The yakuza expect political favors in return, of course, and at least one member of the Diet (legislature) is known to have interfered in a police investigation of a yakuza family.

Justice Minister Keishu Tanaka (pictured) resigned over yakuza ties in 2012. The biggest scandal, though, came in 1992. The New York Times says that year it was revealed the mob played a significant role in getting Noboru Takeshita appointed prime minister in 1987. The politician had called in crime bosses to silence and threaten his political opponents.

Yakuza families are as varied and back-stabbing as real families

Just like the Italian Mafia, the yakuza isn't one single, unified entity. It's made up of an estimated 22 different families, according to Breaking Asia, although no one seems to know for sure exactly how many there are. Their structure and loyalties are complex, secretive, and pretty confusing to outsiders.

Some families are more famous than others. The Kyoto-based Aizukotetsu-kai is the oldest yakuza group still in business; it was founded way back in 1870. Yamaguchi-gumi was the biggest, richest syndicate and had also been around a long time. On its 100th anniversary in 2015, it took in more than $6 billion in revenue. But that same year, it split apart into smaller groups due to infighting.

Then there is the Kodo-kai. Technically a sub-group of the Yamaguchi-gumi family, the Kodo-kai wasn't playing by the rules. They started giving police a harder time than normal, plus they paraded themselves in front of TV cameras, reports the Washington Post. They were setting a bad example, and the cops were forced to act. In 2009, the National Police Agency chief vowed to destroy Kodo-kai. He hasn't succeeded as of this writing, but the Daily Beast says in 2013 there was a major breakthrough when the family's head, the second-biggest gangster in Japan, Kiyoshi Takayama was convicted of extortion. This incident also proved there is no honor among thieves. Government sources revealed the police were aided in their investigation by information from rival family Aizukotetsu-kai, who wanted Kodo-kai off their turf in Kyoto.

Drinking sake bonds yakuza for life

Considering the yakuza go around killing people, it's weird that cops spend some of their time attempting to keep the gangsters from drinking sake. But the yakuza's formal sakazuki ceremony is so important in underworld culture that police try to ban it, reports Kyoto Journal. The pseudo-religious ceremony originated at Shinto weddings, where it cemented the bond between a husband and wife, according to The Yakuza: Pinkyless and Tattooed. So that's the level of seriousness here. When two yakuza dudes perform the ceremony themselves, they consider their subsequent relationship as close as family.

The ceremony is over-the-top formal and would look outdated to a layperson. A room is ritually purified and then an altar is constructed. Three scrolls are placed on the altar to represent three important deities, as well as 12 lit candles and various offerings to the gods, like salt and sea breams. During the ceremony everyone involved acts super proper and uses "highly stylized language" they would never use in real life. The participants drink sake from the same cup and then offer it to the gods as well. After the ceremony they are bonded for life; the less important guy has sworn his undying loyalty to the more important guy.

After they have their sake, the group moves to a bathhouse where they show off their elaborate tattoos, usually freaking out any normal people who are also there. Then they finally let loose, celebrating the new family bond with an outrageous feast.

The yakuza put more thought into their tattoos than who they kill

The yakuza is synonymous with tattoos. At first, it might seem like ink is just another style choice, like their sharp suits and flashy cars, but the artwork on a yakuza's body is actually deeply personal and full of meaning. According to ThoughtCo, the tradition of tattooing goes back to the very beginning of the yakuza, when gamblers covered themselves in ink. Vice reports it might also have to do with an old tactic of criminals to avoid execution by tattooing a symbol of devotion to the government on their necks. Tattooing tradition is so important to the yakuza that many choose to have their work done with old-school bamboo or steel needles instead of modern tattoo guns.

The author of Yakuza Tattoo discovered deciding what artwork to get is a long process. It involves sitting down with the tattoo artist and having numerous interviews until they determine what design is right for the yakuza's personality. The tattoos don't even have to relate to life in the underworld at all. There are various traditional designs that are popular, like dragons, carp, and religious figures. Yakuza will get lots of them, covering much of their bodies including their genitals. (Yes, that hurts a lot.) Because the tattoos are so personal, they usually only get them in places that can be covered up easily in public.

Younger yakuza have started getting Western-style tattoos, something the old guard finds appalling. They think their tattoos should be about tradition, not fashion.

Self-mutilation means never having to say you're sorry

After the tattoos, the missing fingers are probably the most distinctive thing about yakuza. Not all of them are sans a digit, though. If a gangster self-mutilates by yubitsume, literally "finger-shortening," it means the guy has seriously screwed up, according to Next Shark.

To show penance, the naughty yakuza cuts off the tip of his left pinky with a sharp knife. (One dude who did it told an author the experience was "kind of funny" because it was harder to remove than he expected, and he also sang the Super Mario theme throughout for some reason.) They then present the fingertip to their boss, who sometimes keeps it on display. If they screw up again, more pinky comes off, until the left one is gone. Then they move onto the right. (Or just stop messing up, maybe?!)

The idea originated back in the days when men still used swords. The pinky is important when it comes to gripping a sword firmly, so every time it's shortened, the mutilated person becomes more dependent on the group as a whole to protect him since his sword skills will no longer be top-notch. But not everyone stays in the yakuza for life. If a guy who has committed yubitsume leaves the world of crime behind, everyone in the regular world will be able to mark him as a former yakuza because of the missing finger. ABC News reports many will have fancy custom-made prosthetic pinkies to help disguise their seedy past.

Women have it incredibly hard

A yakuza member is, by definition, a man. A woman, no matter how involved she is with organized crime, is not considered a yakuza. That leaves the women of the underworld in a weird position.

One photographer wanted to learn about this hidden part of the mob and found the women had to get permission from their husbands to have their picture taken. Sometimes wives and mistresses of yakuza members work as hostesses in clubs owned by the gangs, entertaining other men to make money for their men back home. Women married to the top gangsters often have bodyguards (always female), but they have absolutely no power in the organization, relegated to a "passive emotionally and financially supportive role." Despite this, women connected to the yakuza also get massive tattoos to cement their association.

Because of the nature of criminal groups, the women end up isolated. They stick together, not usually making friends with regular civilians. Their path to the underworld varies: Many women just meet a guy, fall in love, and then it turns out he's a yakuza. Others are born into it. The Guardian interviewed the daughter of a mob boss who said she hated how her father and his associates behaved. Despite this, as a teen she "behaved exactly like a junior yakuza, picking fights and not caring about how other people felt." Her life was horrific, including assaults by men her father owed favors to. Fortunately, she got out, but she's still judged for her tattoos.

They take time out from all the murdering to do charity work

The yakuza are famous in Japan for their criminal enterprises, ruthlessness ... and charity work? Somehow, the country's gangsters have also become one of the most altruistic groups around. They are especially known for jumping into action after major disasters.

According to the Daily Beast, after the 1995 Kobe earthquake, the yakuza was "one of the most responsive forces on the ground, quickly getting supplies to the affected areas and distributing them to the locals" while the government took forever getting aid to people. The mob would do even more after the infamous 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami, sending in 70 trucks filled with $500,000 in supplies within weeks. They jumped into action again after the 2017 earthquakes.

While the yakuza claim their code of honor demands they help suffering people, some police officers quoted in the Independent think all isn't as nice as it seems. They say the yakuza may be raising money for relief and then skimming some off the top or making connections with people who will need their (legal) construction services after the disaster. But it might actually be down to altruism, since Reuters reports the yakuza "shun the spotlight regarding their relief work." They also often hide evidence of their connections to the supplies, out of fear that people will refuse them since they came from bad guys. But even when the secret gets out, everything is usually accepted, since when people need food and blankets, they don't much care who's supplying them.

The yakuza are on the decline — maybe

The yakuza's days may be numbered. Not just because of the increasingly harsh laws against organized crime, but because millennials have added it to the list of things they're killing. Yes, like napkins, top sheets, and home ownership, young people may be the end of mobsters. As of 2017, yakuza membership had fallen 13 years in a row, according to the South China Morning Post. That year there were 34,500 members, and fewer than 20,000 of those individuals were considered "core members." Compare that to the peak of 184,000 yakuza members in 1964. Even if millennials wanted to join, they might not be good enough. One crime boss lamented that "the younger generation lacks that hungry spirit that rebuilt postwar Japan."

Authorities have come up with creative ways to turn young people off joining or help them leave. In one district, turning in a grenade gets you $1,000. The local government also offers assistance to broke mobsters who want help getting a legitimate job. The courts are also finally allowing yakuza members who turn police informants to change their names to make going into hiding easier. (For record-keeping purposes, Japan usually rejects requests to alter personal information that is registered at birth.)

One expert thinks the yakuza will hold out until the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo (which will make them a lot of money from construction) and then rapidly disappear. However, another says the gangsters aren't really in trouble, they're just getting better at hiding and continue to thrive in the shadows.