What It Was Like The Day Martin Luther King Jr. Died

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination shook the world. Despite the fact that the murder was and remains extremely well-known, we still don't know everything about MLK's death, thanks to several unsolved aspects of the case and the various authorities' attitudes and competence issues in the aftermath. However, after King was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel during his visit to Memphis, Tennessee, the timeline of events is clear. The public raged and rioted in many cities, leading to over 40 deaths, 3,500 injuries, and an estimated 27,000 arrests. The culprit, James Earl Ray, initially pleaded guilty but later recanted. As a result, King's death has long been the subject of conspiracy theories about government involvement in the assassination.

But how did things play out on the very day King was assassinated? How did the many people King had influenced react in the immediate aftermath of his shooting, and in what ways did the day set up the difficult path ahead? Here's a look at what it was like on the day Martin Luther King Jr. died.

James Earl Ray started his escape

At around 3 p.m. on April 4, 1968, the man who would soon become Martin Luther King Jr.'s killer, James Earl Ray, used a fake name to rent a room from a lodging house near the Lorraine Motel. He went on to buy some binoculars and started staking out the motel. He spotted King on the balcony mere hours after checking in to the room, and fatally shot the civil rights leader from a bathroom window at 6:01 p.m.

Witnesses had noticed where the shot came from, but by the time the police entered the building, Ray was nowhere to be found. His rifle and equipment were found nearby, but the assassin himself had already driven away in a white Ford Mustang.

Ray left the car in Atlanta and switched to a bus during what was the start of a lengthy international escape — first to Canada and then Europe. He already had plenty of experience evading authorities before the assassination, since he was an escaped convict who had been on the loose since April 23, 1967, and was skilled at using aliases. It took until April 19 for the authorities to identify him, and he was able to stay on the run until June 8, when he was detained at London's Heathrow Airport in possession of a gun and two different fake passports.

King could have left the motel an hour before the assassination

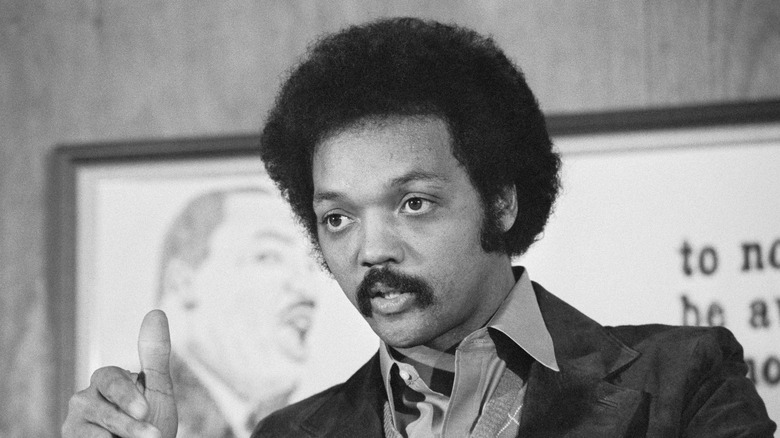

Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Memphis the day before his death to support a local sanitation workers' strike, which was a part of the larger Poor People's Campaign that he led. Another prominent civil rights leader at the time, Reverend Jesse Jackson, was with King when he died. In an interview with History, Jackson noted that they were supposed to attend a dinner together. However, they were running late, and were just sparring verbally about proper attire and whose fault the delay was when the bullet hit.

"He said, 'Jesse, you're an hour late,'" Jackson described the events that took place moments before King's death at 6:01 p.m. "I said, 'Doc, you an hour late.' I said, 'We've been waiting for you.' He said, 'You don't even have on a shirt and tie, and we going to Reverend Kyles' home for dinner.' I said, 'Dr. King, the prerequisite for eating is an appetite — not a tie.' He said, 'You're crazy.' We laughed."

It's impossible to say whether King would have lived through April 4, 1968, if they'd left the Lorraine Motel at 5 p.m., as Jackson said they originally meant to. However, it's worth noting that James Earl Ray had already started watching the motel sometime before 6 p.m., so the danger was already present before that time.

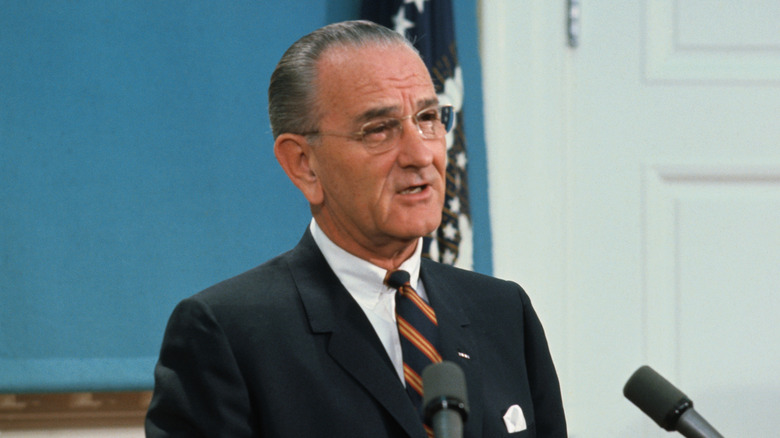

President Lyndon B. Johnson was quick to react to King's death

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr. knew each other fairly well, and had often collaborated in civil rights matters both openly and behind closed doors. While King's openly critical attitude toward the Vietnam War had considerably strained this partnership of sorts, Johnson still recognized King's importance and influence. As such, he dropped everything after hearing the news of King's death on April 4, 1968, and addressed the nation in a televised speech that same day.

"America is shocked and saddened by the brutal slaying tonight of Dr. Martin Luther King," Johnson said (via the University of California's American Presidency Project). "I ask every citizen to reject the blind violence that has struck Dr. King, who lived by nonviolence. I pray that his family can find comfort in the memory of all he tried to do for the land he loved so well."

Johnson spent his short speech honoring King and his deeds, and imploring Americans to remain calm in the wake of the tragedy. To drive home how impactful the situation was, he also specifically noted that the incident had caused him to clear his schedule for the remainder of the day. The president wasn't exaggerating how King's death made him feel, either. "I have rarely felt that sense of powerlessness more acutely than the day Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed," he would later admit (via the National Park Service).

Some unrest erupted in Memphis

Even in the age of social media and constant access to news outlets, the protests that started after the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 in Minneapolis didn't truly start in the city until May 26, and took until May 27 to start in other cities. As such, it's noteworthy just how quickly the crowds reacted after Martin Luther King Jr. died.

In the wake of King's death, The U.S. plunged into disarray with a series of violent incidents known as the King assassination riots. However, what people might not realize is just how quickly this happened in Memphis. King was shot at 6:01 p.m., and signs of rioting started showing that very same day. The government dispatched 4,000 National Guard members to Memphis, but the unrest soon turned out to be nationwide and extremely difficult to contain. Mere hours after the assassination, several cities were dealing with riots which went on to rage for days. At the end of the day, however, Memphis was one of the calmer cities during the riots, despite the fact that King had died there. That's not to say the city didn't see any crowds, though — on the contrary, some 42,000 people attended a silent march in King's remembrance on April 8.

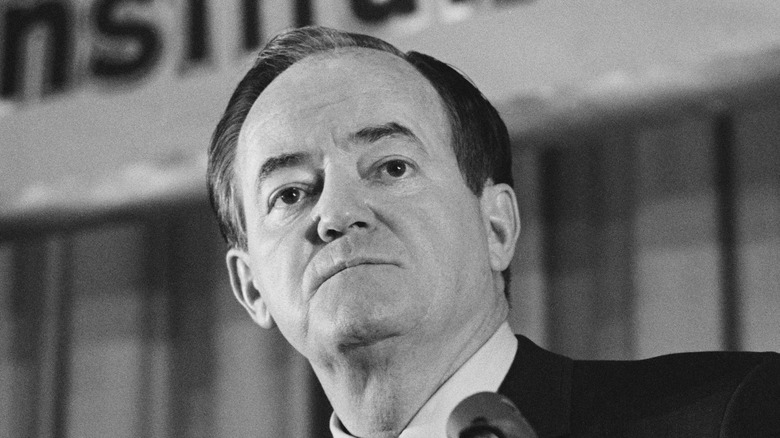

Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced the death in a massive Democratic event

President Lyndon B. Johnson wasn't kidding when he said he canceled his April 4, 1968 plans after learning of Martin Luther King Jr.'s death. Apart from postponing his travel plans, he also skipped a Congressional dinner event involving himself, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, and 2,500 Democrats at the Washington Hilton Hotel. Humphrey and guests were already at the hotel, however, and the clearly moved vice president was tasked with announcing the tragic situation to the attendees.

"This is a very unusual and special and very difficult time," Humphrey said (via The New York Times). "A great tragedy has taken place in America tonight. One of our renowned and active leaders in the cause of civil rights has been stricken down by an assassin's bullet. Martin Luther King has been shot and is dead. The criminal act that took his life brings shame to our country. The apostle of nonviolence has been the victim of violence."

Humphrey went on to express a confident belief that King's non-violent civil rights cause would live on and shape society. Nevertheless, after such terrible news, it's not exactly a surprise that the dinner event was ended prematurely soon after his speech.

Tensions in Washington D.C. reached boiling point

The people of Washington D.C. learned of Martin Luther King Jr.'s death at around 8 p.m., and tempers boiled over almost immediately. Apart from the tensions that were gripping the country, the city's poorer, predominantly Black neighborhoods were already on a state of alert after a recent altercation. After the radio started spreading the news, furious people started taking to the streets. King's friend Stokely Carmichael – an activist who was at the scene and led a large crowd in the early stages of the events — soon saw the situation escalate into an uncontainable riot.

Looting, violence, and arson ran rampant well before midnight, and first responders were hopelessly outnumbered. The following days were pure chaos, with rioters — some of them armed — causing chaos, with everyone from the Secret Service to firefighters trying to do their jobs in the difficult conditions. By the time the fires went out and the dust settled, entire city blocks were destroyed and 7,600 people had been arrested. The estimated material damage of the D.C. riots was well over $200 million, adjusted for inflation.

King's death may have been the spark that lit the fires, but as former Washington D.C. councilwoman Charlene Drew Jarvis told The Washington Post, the city's own history of segregating its population fueled the flames. "A lot of it had to do with, 'We've been contained here. We're angry about this. We owe nothing to people who have confined us,'" she said.

Robert F. Kennedy gave a very personal speech

After the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, Senator Robert F. Kennedy kept the family's political torch alight and was heading toward presidential candidacy himself in 1968. On April 4, Kennedy was set to give a speech in Indianapolis. When he heard of Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, he immediately used the platform to address the situation.

Kennedy broke the news to a campaign rally audience and advocated for non-violent solutions in the face of the tragedy. "We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization — Black people amongst Black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another," he spoke (via the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum). "Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love."

The emotional Kennedy had only just learned of King's death himself and had to put the speech together on the fly, hastily creating a powerful, personal speech in which he publicly discussed his brother's assassination. As a chilling moment of foreshadowing, he also recognized the trend of prominent civil rights-focused leaders getting assassinated. "It could have been me," he allegedly told a campaign staffer later that night (per Smithsonian Magazine). On June 5, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy tragically died when Sirhan Sirhan shot him in Los Angeles.

New York Mayor John Lindsay took a walk in Harlem

When the news of Martin Luther King Jr.'s death reached New York City on the evening of April 4, 1968, Mayor John Lindsay feared rioting and made a beeline to Harlem to meet the people. Lindsay told journalists the following day that the general mood in the area was that of despair, saying, "I most certainly found the mood in New York City during my tours last night to be one of great grief, emotion, very deep emotion, with people weeping, and frustrated and lonely. And terribly lost and let down."

Lindsay's decision to get personally involved played a role in preventing major riots in New York, which was a very legitimate threat considering the city's history of civil unrest in recent years. He had a policy of communicating with Black community leaders of all sorts, and had a better standing among them than a politician could usually dream of.

By spending much of the night walking in Harlem, he was able to personally talk to people and express regret for what had happened. He made sure that the police presence didn't create too much tension, discussed matters with notable neighborhood figures, and did whatever he could to ease people's minds. In the end, the city did see some trouble — but only a small fraction of what was going on in Washington D.C., with only 12 arrests made.

Avondale, Cincinnati slowly started the road to rioting

The Avondale neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio, didn't get violent on April 4, 1968, when it heard about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Instead, it got angry. In June 1967, the area had already gone through a 1,000-strong race riot — one of the 159 that took place all over America during that summer. In the wake of King's death, the population simply seethed ... at least, at first.

Avondale may have spent the evening of April 4 — and some days after that — in quiet fury, but when a rumor about a white police officer shooting a Black woman started spreading among the crowd during a King memorial ceremony on April 8, a full-blown riot was unleashed. Two people died in the riots, which caused close to $28 million (adjusted for inflation) in property damage. The long-term cost to the area was also steep, as more affluent residents soon relocated to other places; the once pleasant neighborhood became a dwindling area that was still littered with burned rubble and a bad reputation.

Detroit's riots didn't make major headlines (this time)

The people of Michigan remembered Martin Luther King Jr. fondly for his recent visits to Detroit and Grosse Pointe, so when the news of his death reached the state, a crowd started gathering before the day ended. However, since Detroit's two biggest newspapers were temporarily out of commission due to a strike, the events had difficulty making headlines in the big papers. As such, a smaller paper, The Windsor Star, followed Detroit's events and pieced together what it could.

Things didn't get truly unruly in Detroit's 12th Street area until after midnight, although one young person died during the events. Still, compared to the riot that took place in the same area a year before King's death, things stayed relatively calm. The 1967 Detroit riots erupted amidst high tensions in the city when the police raided an illegal club late at night. The unrest this caused created a domino effect and became a giant four-day riot that killed 43 people and burned down almost 1,400 buildings. It's still considered one of the worst riots in the country's history, and many of the buildings it destroyed remained in ruins. In fact, this particular incident had caused much strife to King, as it and other recent events contributed to the civil rights leader's decision to travel to Memphis — where he was killed — in 1968.

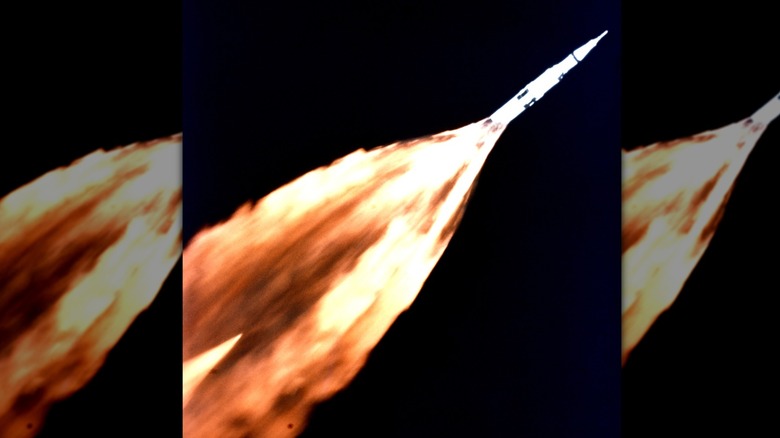

In the middle of it all, the Apollo program quietly had a bad day

While the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. was doubtlessly the most tragic and impactful American event of April 4, 1968, it wasn't the only thing that took place that day. As it turns out, NASA had a pretty bad day as well, for entirely unrelated reasons. The Apollo 11 Moon landing on July 20, 1969, was still some time and effort away, and the space agency was testing the Saturn 5 rocket with an unmanned Apollo 6 mission. While it came at the heels of two Apollo program missions that had gone very well, this time things went wrong almost immediately.

Two minutes after launch, the spacecraft violently vibrated for half a minute. A series of rocket malfunctions followed, and the craft ultimately failed its intended purpose. "There's no question that it's less than a perfect mission," Apollo program director Samuel C. Phillips said (via the NASA special publication "Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations").

Apollo 6 ended up providing more information about weird malfunctions that needed to be fixed than actual success, but the data it provided was useful. NASA was able to solve the vibration issue it had dubbed the pogo effect, and could move on to manned space flights.