Eerie Mysteries About The Devil That Are Still Unsolved

The devil's pretty scary. Of course, that's his thing, what with being the biggest evildoer and chief deceiver of all time, according to many adherents of Abrahamic religions like Christianity. But, for as much as he occupies an outsized space in many imaginations, how much do we really know about the devil? If we only go by what are widely considered to be canonical texts, such as the Christian Bible or Muslim Quran, there's precious little out there to explain what the devil is doing, much less why he's doing it and how he got there in the first place.

Peek into apocryphal religious texts and widely-held folklore beliefs, and things get even more confusing. After a while, looking at all of the details that we don't understand or even the many things we get wrong about the devil, you may even start to feel seriously unnerved. If the devil is supposed to be this bad, why is our ability to understand — and if you believe, identify — this figure so inconsistent? It's led to some lingering eerie mysteries that we have yet to solve, despite the hundreds and even thousands of years we've had in which to ponder them.

Where did the devil come from?

In many Christian traditions, the devil is no less than the personification of evil. But where exactly did he come from? The Bible doesn't contain many clues, if any. Isaiah 14:12-17 refers to a Lucifer who attempted to gain prominence over God and was cast out of heaven and thrown in hell as a result. But is this Satan? Nothing in the text strictly says so, though that's been enough for some people to connect the dots and say that the devil is this very Lucifer. That was certainly the inspiration behind John Milton's 17th-century epic poem, "Paradise Lost," in which Lucifer becomes a darkly compelling antihero and a figure that looms large over our modern perception of the devil.

But then there's evidence that at least one version of Satan was actually an associate of God. In the Book of Job, a figure referred to in the Hebrew text as "ha-satan" acts as an adversary who comes across as more like a functionary in God's domain than an independent evildoer. That may have at least some roots in earlier religious traditions, such as Zoroastrianism, once the state religion of ancient Persia, that maintained that the wise and good Ahura Mazda faced off against the chaotic Ahriman. When large numbers of Jewish people were taken to Babylon as captives in the sixth century B.C., it could be that they folded this idea into their own religious beliefs and brought it back home with them.

Does he really rule over hell?

While there are plenty of stories about the devil roaming the earth and tempting mere mortals, many also have him go back to a home base of sorts: hell. But does he really go there, or even rule over it, as quite a few legends maintain? Not necessarily. There are biblical hints that he's been banished there, assuming you accept the proposal that the devil and figures like Lucifer are one and the same.

But being imprisoned in a place is hardly evidence that you've got control of the same spot. For the development of that notion, we have both John Milton and medieval poet Dante Alighieri to thank. In "Paradise Lost," Milton has Satan defiantly declare that it is "Better to reign in Hell, then Serve in Heav'n." In fact, Satan's whole thing in Milton's work is that he wants to rule over something, and though hell is a poor comparison to the glories of Milton's heaven, it's seemingly better than nothing at all.

As for Dante, little in his epic work, "The Divine Comedy," explicitly states that the devil has power over the elaborate hellscape that Dante traverses in the first section, known as the "Inferno." Instead, he's a gigantic demon, half-frozen in the ice, weeping while he chews on the bodies of betrayers. Despite his literally looming presence, it's hard to believe that he's really in charge here. From a religious perspective, the devil's position in hell remains pretty obscure.

No one knows what the devil is meant to like

Over generations, many writers and artists have imagined the appearance of the devil. But the sheer variety of those depictions — is he a beautiful angel plummeting to Earth? A grotesque demon in a dark pit? A hunky rebel? — belie the truth. We have no clue what the devil is really supposed to look like. At least, not if we're trying to go off the Christian Bible.

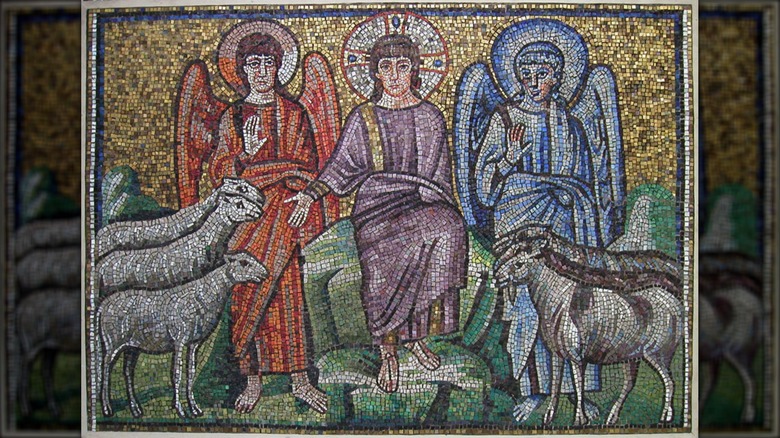

Some early depictions even put the devil in close visual quarters with angels. In Ravenna, Italy, a sixth-century Byzantine mosaic in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo appears to have the earliest known depiction of Lucifer. Yet, instead of glowering from hell, this Satan sits to the left of Jesus, depicted in a serene blue while standing before a trio of goats. That's a reference to Matthew 25:31-46, in which Jesus is predicted to separate the believers (sheep) from the unbelievers (goats), sending the devilish goats off to eternal punishment. But this devil looks hardly devilish and, in fact, appears almost identical to the red-clad angel watching over the sheep.

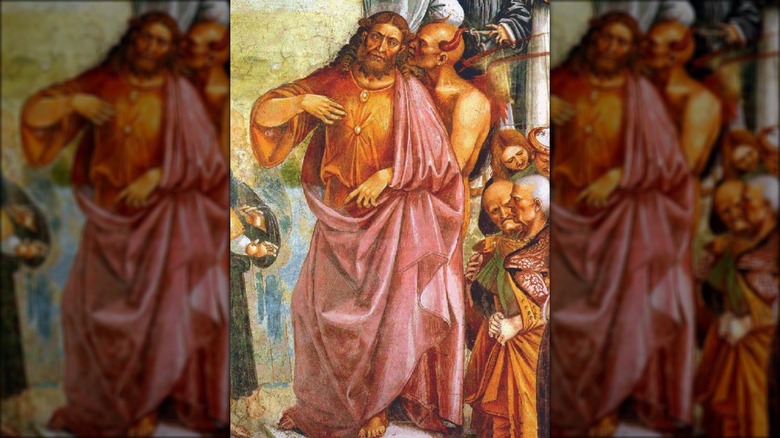

So, how did we get to the horned, hairy, goat-hoofed version of the devil? It could be that medieval artists who depicted the devil as an animalistic demon drew inspiration from pagan gods, like the ancient Greeks' half-goat Pan, in conjunction with the association between Satan and goats established in Matthew.

Was the devil behind a troublesome census or not?

King David clearly had a complicated relationship with God. The ancient ruler of Israel, who rose to fame for uniting the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, is a prominent figure in the Hebrew scriptures. But while he was a highly successful ruler who sometimes seemed beloved by God, he experienced all manner of personal upset, from quarrels over his heir to an especially difficult episode in which he allowed a woman's husband to die in battle so he could marry her.

But, at least sometimes, it may have been that the instructions David received were confusing. Take the affair of the census. In 2 Samuel 24, God commands David to take a count of those in his kingdom who were in fighting form. Only, he then experiences great remorse and fears God's wrath — presumably because he was counting something that didn't belong to anyone but God. Yet in 1 Chronicles 21, the same incident is retold, but this time it's Satan who's pushing David to do the sinful counting. Either way, David's subjects are hit with a terrible plague for their king's mistake.

So, who's in charge here? Some have suggested that God allowed Satan to tempt David as a sort of test. But God never seems willing to give an explanation as to why he would loosen Satan's reins a bit, leaving some to wonder if that's the right explanation for this odd discrepancy and what becomes a bureaucratic nightmare.

Is the devil always evil?

Asking whether the devil is evil might seem like a silly question. But the early history of the Christian devil does introduce some complicated questions in that arena. Consider the earliest known depiction of Satan, a sixth-century Italian mosaic in which he's depicted as a blue-tinged angel sitting next to Jesus and seemingly doing the will of the divine.

Some stories depicting the devil introduce the idea that perhaps evil isn't always his game. In the Old Testament book of Job, Satan appears in Job 1:6-22 as a kind of prosecuting attorney in direct communication with God. When God speaks glowingly of the faithful, upstanding man named Job, Satan asks, "Doth Job fear God for nought?" Perhaps, if God stops giving Job such an easy life, the man's faith will wither. And indeed, God gives Satan the power to mess up Job's life, imparting a vague but powerful lesson about the unknowable nature of God and divine will.

Here, Satan — whose name may more accurately translate to a title like the Accuser or Adversary — might actually be more like a prosecuting attorney in the employ of God rather than the rebellious, evil-causing devil as we know him. Likewise, mystical Sufi traditions within Islam have sometimes held up Iblis (essentially the Muslim version of Satan) as a rightful rebel who refuses to bow before Adam and only wishes to worship Allah.

Is the serpent also the devil?

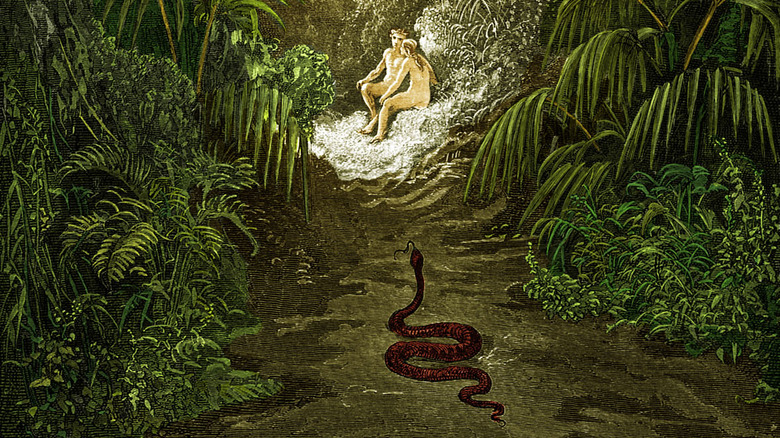

In retellings of Genesis, the devil is the very serpent who tempts Eve into chowing down forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. In Genesis 3, he challenges Eve to go ahead and eat from a previously verboten tree, claiming, "God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil." Sure sounds pretty devilish.

Only, the true identity of that serpent isn't actually made clear. Sure, it would make narrative sense for a key figure in the downfall of humanity to be the devil, but the Bible never gets around to specifying that it's Satan in snake form who infiltrated Eden. In fact, the Hebrew scriptures that make up the Old Testament never strictly define a singular devil figure at all (the satan referred to in Job isn't clearly more than a challenging angel working in concert with God).

It was only during the period between when the Old Testament texts were written and when the Greek books of the New Testament began to be written that Jewish theologians began to propose the idea of a primary adversary known as the devil. Even then, the serpent seems to have remained a serpent. Nothing or no one in the New Testament tried to obviously connect the human-tempting creature with the solidifying figure of the devil, though snakes definitely had an evil, demonic reputation for writers like the author of Revelation.

What's the devil's name?

A basic name gets complicated when you start to consider what to call some of the biggest figures in the Bible. Take God, for instance, whose name is considered so sacred by some Jewish and Christian people that they instead use an abbreviated form or any one of many titles to show their respect. For a variety of reasons throughout history, God's been known as Elohim, Yahweh, Adonai, and Kyrios, just to name a few.

Things are even thornier and mysterious when it comes to naming the devil. He's also been given a variety of names and titles throughout the Bible, leading to quite a lot of confusion as to whether or not we're all talking about the same dastardly figure or many. Is the plummeting Lucifer of Isaiah 14:12-17 the same as Satan? Are Beelzebub, Mephistopheles, Moloch, and Baphomet all names for one being, some of the seven princes of hell, or lieutenants of the dark lord (as 16th-century occultist Johann Weyer argued in his "Pseudomonarchia Daemonum")? It doesn't help that some humans are referred to in Greek Biblical texts as diabolos, or devils, like when an incautious reader might mistakenly believe that the human Haman in Esther 3 is literally devilish.

Ultimately, the Bible leaves us with more questions about the devil's name than answers. Looking into extra-Biblical sources like folklore hardly clears things up, either. Instead, we're left with a serious and lingering mystery as to what to call the devil.

What does the devil's existence say about the power of God?

Even if the secret history of devil meant that he just sat around and did nothing, he still represents an especially chilling mystery. If we assume the devil is the embodiment of evil in a world run by a good and just God, it quickly presents a thorny issue.

It could be that God is totally in control and yet still allows horrible things — like, say, the embodied of all evil who loves to tempt humans into mortal sin — to exist. Or, if not that, then those awful situations run rampant because divine power isn't quite as strong as we may hope it to be. A third possibility in this problem is that perhaps God isn't all that just and good to begin with. That's the basis for the philosophical and religious quandary popularly known as the problem of evil.

To many, that's an overly simplistic view of evil and the devil. Some go the theodicy route, claiming that evil — and, by extension, the power we grant to the devil — is a consequence of our troublesome free will and resulting ability to sin (though perhaps it still doesn't satisfy the follow-up question as to why God allows for sin in his system in the first place). Others may say that God's design is beyond human comprehension, perhaps meaning that even the devil doesn't totally understand why he's allowed to continue doing his evil thing.

Why is the devil different in Judaism and Islam?

While the devil has a place in Christianity, it's not the only Abrahamic religion in which he appears and generates uncomfortable ideas. In Judaism, Satan is a being that appears from time to time (after all, the Bible's Old Testament is part of the Jewish scriptural canon, though some details differ). However, in most Jewish theological discussions, he's more representative of the wayward path and humanity's temptation than one evil figure.

The devil is more of an individual in Muslim accounts, where he raises some disconcerting questions that aren't always answered. In the Quran 17:61-65 (as well as in other spots throughout the scriptures), an angel named Iblis refuses to bow before the human Adam, even when commanded by Allah. Iblis is banished, but not before he promises to tempt humanity — with God's permission. In other parts of the text, humans like Adam and Eve are tempted by shaitan, spirits that follow Iblis.

However, Islamic mystics like the Sufis have wondered if maybe Iblis wasn't so off base. As some medieval thinkers argued, Iblis was only showing his true, unadulterated devotion to Allah by refusing to effectively worship another. But was this a legitimate interpretation or part of the Sufi trend towards heresy and public humiliation in order to humble themselves and reach a higher sense of spirituality? That's hard to tell, but it introduces the rather chilling and perplexing argument that the devil may have been on to something.

What's really his part in the apocalypse?

Of course, the devil will have something to do with the end of the world. But what exactly is his role in the apocalypse? That's more mysterious, even to close readers of the Bible and other religious texts. Most interpretations of the apocalyptic Book of Revelation maintain that the Antichrist, said to emerge in the end times, will act in the devil's stead on earth — pretty darn bad, considering that the Antichrist is predicted to take control of the world.

But, as the Book of Revelation claims, Satan himself isn't strictly on the ground when the apocalypse gets rolling. John the Elder, believed to be the man who wrote Revelation sometime around A.D. 100 on the Mediterranean island of Patmos, doesn't really make things clear with his many notations of a beast and deceiver (as well as no obvious mention of an antichrist, who many take to be John's deceiving beast).

In Revelation 20:1-5, he does maintain that Satan is chained up in the Abyss for much of the end times. But after 1,000 years of a returned Christ ruling over the Earth, Satan is to be set free to do his evil thing in the final battle between his forces and those of God. But the specifics of what he is supposed to do, how he's supposed to do it, and who exactly his agents are to be and how they'll operate, are hard to parse in John's dense, highly symbolic text.