Things About Roman Mythology They Didn't Teach You In School

Ancient mythologies are a vastly underrated part of our collective history, and they say perhaps more about how little the human race has changed than any kind of history-is-written-by-the-winners sort of adaptation of real events. The stories and gods of Roman mythology were largely adapted from earlier Greek tales. One of the best literary sources is the Roman poet Virgil, who told the tale of Aeneus leaving Troy, heading to Italy, and not only taking his stories with him, but kick-starting the Roman world.

And that's important, because there are plenty of Roman tales that sound pretty familiar to those who have read some of the absolutely amazing stories from Greek mythology. And just like there are plenty of stories from Greek mythology that they didn't teach you in school, there's a lot of Roman lore that gets swept under the rug of what's convenient to hide from kids.

There's a bit of a footnote that comes with this, too: It isn't just the stories that have some questionable ratings, it's the real-life events that stem from those gods, divine orders, and practices. Roman gods and goddesses shaped the ancient world. For some people, well, let's just say that it wasn't always good news.

Sterculius: the all-knowing (maybe), all-seeing (probably) God of Poops

Anyone who's ever been in the general vicinity of a child will understand why this one was left out of schools: Sterculius was the Roman god of poops, which would undoubtedly entertain every 13-year-old in the school for at least a good week. That said, Sterculius actually had a more specific place in Roman mythology that's pretty logical. Details are a little foggy, but it seems that he's connected to Picumnus, who was the son of one of Rome's major agricultural gods, Faunus. Faunus — who could appear in either a male or female form — was connected to livestock, farming, and prophecy, and it was Sterculius who brought humankind knowledge of using manure as fertilizer.

So: god of poops. While that's hilarious, it's easy to see how ancient Romans thought he would be a big deal. He gets a mention in Pliny the Younger's "Historia Naturalis" and credit for introducing the world to fertilizer, and he's definitely not alone in the pantheon of weird gods that seem like they've been dropped out of the pages of a Terry Pratchett novel.

There were a ton of minor gods who oversaw almost every aspect of life. Worried about an approaching storm? Pray to Commoleda, who was strictly tasked with keeping trees safe from lightning. There was even Cardea, the goddess of door hinges. Like Sterculius, she was extremely important, too, and kept everyone in the home safe from intruders both corporeal and supernatural.

Bacchus bestowed his female followers with the strength to rip a person to pieces

Bacchus is the Roman version of the Greek Dionysus, so it's not surprising they share backgrounds, characteristics, and stories. Among those are the tales of their female followers, and given that he's the god of winemaking (among other things), it makes sense that it's going to get a little freaky. But the maenads? They're a whole other level of yikes.

The maenads — who were more frequently called the "bacchants" in the Roman traditions — were followers of Bacchus who would be driven into a mad, violent frenzy. In some mythologies, the female population of entire cities was turned to maenads who fled to live their best, wild lives in the mountains and forests. (It supposedly happened, for example, in Thebes.)

There, it was said that they could summon springs of wine, and after partaking, they would descend into a supernatural frenzy of dancing and celebration... and no one could save those who got in their way. Along with the ability to set their hair on fire and not burn, they had the strength to tear entire animals — particularly cattle — into pieces with their bare hands, and would turn that rage on any person who crossed them, as well. Sometimes, they were used as weapons, sent out as avenging angels hellbent on destroying those who had offended Bacchus. They were said to destroy entire villages, kidnap children, and then bathe in their wine-filled springs afterwards.

Dogs had an important place in Roman mythology... as sacrifices

Animal and human sacrifices are found throughout ancient mythology, and that's the case for (hu)man's best friends, too. (For the dog-lovers, it's all right: We're not going to get into the grisly specifics of this one, because there's nothing that ruins a story like the death of a dog.) Dogs had an incredibly important place in both Roman mythology and the real world: They could not only see the supernatural, but they were also protectors of the home, family, and flock. Unfortunately, when it came time to appease the gods and ensure an abundant harvest, well, dogs were front and center there, too.

The sacrifice of red dogs — and sometimes red puppies — was at the center of a festival called Robigalia. Robigus was the god of not only rust and mildew, but of the kind of blight that can destroy entire fields of crops. He was apparently appeased by the sacrifice of dogs, making him someone that we definitely are putting on a list of some sort... and not a good one.

Dogs were also sacrificed to deities called the Lares Praestites — by priests who would also wear their skins — and to Hontia, an Umbrian goddess of destruction. Those sacrifices were meant in the standard sort of appeasing-evil kind of way, and here's an extra-terrible footnote: Puppies were considered pure creatures, which made them not only perfect sacrifices, but the ideal main courses in banquets honoring the various gods.

The time Hercules killed a man and was sentenced to become a crossdressing sex slave

Everyone's heard about the labors of Hercules, and even if they can't name them all, they know there's a lot of completing impossible tasks and killing reportedly unkillable monsters. Less often re-told is the story of how he killed a guy and was sentenced to spend a few years as the slave of a Lydian queen named Omphale.

The Hercules-Omphale story was a favorite for Roman artists, and it was featured on everything from mosaics to coins. It started post-Labors, when Hercules participated in a contest to win the hand of a princess. (He'd already been married and had children, but he killed his family... so it's fine.) Hercules won, and the king — not wanting his daughter to meet the same fate as Hercules' previous wife, backed out of the deal. Hercules was perhaps predictably seized by one of his murderous rages and killed the king's son, Iphitos. As punishment, he was given to the Lydian queen Omphale as a slave.

Part of the deal was that Hercules was to spend his sentence wearing women's clothing and doing chores that traditionally belonged to women, like spinning and weaving. Omphale, meanwhile, was often portrayed as wearing his Nemean lion-skin clothing, and according to the writings of Tertullian, his sentence absolutely included being her sexual slave. The set-up must have worked for them: After releasing him from slavery, she married him.

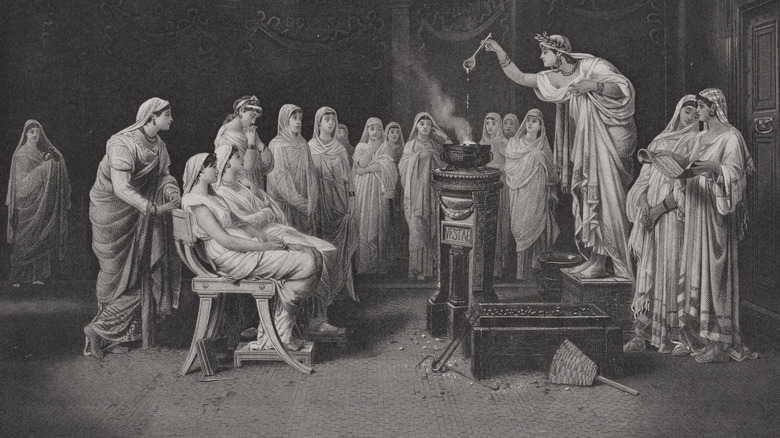

Accusations of impropriety could end a Vestal Virgin's life in an unthinkable way

The Vestal Virgins were established in the seventh century B.C., when Roman king Numa Pompilius created provisions for the support of a group of women dedicated to tending the fire of the goddess of the home and hearth, Vesta. It was believed that Vesta would protect Rome, her citizens, and her soldiers as long as she was honored, and it was a huge deal. While it came with restrictions — Vestal Virgins couldn't marry — they were allowed to own property, vote (and contribute to political discussions), and free slaves, and they were protected by the highest and harshest of laws.

That said, they were also subjected to them. A Vestal Virgin accused of letting the fire go out would be stripped naked and whipped. If she was accused of breaking her vow of chastity, the Romans had an even worse punishment in store for her.

That was being buried alive, only there's a caveat. No one was actually allowed to be buried in the city proper, so instead, women declared guilty were sealed in a subterranean room with enough food and water to survive for a little bit... but not for long. It's unclear just how many women were executed that way, but there were at least a few — and some came face-to-face with the possibility for some ridiculous reasons. One woman named Postumia avoided death and was only reprimanded. Her crime? A fondness for telling jokes.

The Roman origins of Valentine's Day were rooted in an X-rated orgy with ritual sacrifice

Valentine's Day is a love-it-or-hate-it holiday, with chocolates, overpriced flowers, ritual sacrifice... wait, what? Exactly how Valentine's Day came about is up for debate, but one of the oft-told tales is that it has roots in the ancient Roman festival Lupercalia. That's one of their many festivals and one that was linked with fertility and childbirth, and that's fine. Don't worry, it's going to get not-so-fine.

Part of the ritual aspect of the festival was the slaughter of goats (and by some accounts, dogs as well), which were then skinned by priests called Luperci. The skins were cut into strips, and the priests — who were, of course, naked for the entirety of the ritual — would then chase Roman women (who were also sometimes naked) and flog them with goat skin. Just how serious of a beating this was is debated... like, honestly, a lot of things about Roman mythology.

There's another piece of Lupercalia that's debated, and that's the story that men and women would draw names from a jar and be coupled up — in every sense of the word — for the festival. Although some historians say that's highly unlikely because of the numbers of available men and women, others say that the couples would be free to go their merry ways at the end of the festival but oftentimes, they chose to stay together. Modern dating doesn't look so bad now, does it?

Roman mythology had the best (or worst) imaginable ghosts

Dungeons & Dragons is amazing, and that's a hill to die on. In spite of D&D's rocky start and ridiculous history, it's remained popular for decades... and anyone who has played can tell you why. (For hours on end.) The D&D books have been filled with countless Easter eggs and references to creatures from throughout world mythology, and that includes the lemures. In the game, they're fleshy ooze-puddles that exist in mindless agony, acting on behalf of higher-ups in Avernus (Hell), and... that's actually pretty much plucked from Roman mythology.

There's a few different ways in which Roman lemures were made: Sometimes, they were souls that weren't given proper burial, sometimes they were the remnants of people who had been murdered, and sometimes, they were just evil jerks. And they were everywhere. Want to really scare the kiddos? Teach them this one in school: All of those strange, unearthly, inexplicable noises that happen at night? Those are the hideous dead remnants of the worst people to walk the earth, coming back for no other reason than to deliver the most unthinkable, unspeakable cruelty on the living. Fun!

Lemures tended to target their old homes, because some things never change. Keeping them away took not just one ritual, but a series of rituals performed by each household on May 9, 11, and 13. That would keep them away for another year, but even gods couldn't help you if you didn't perform the protection rites like annual clockwork.

Rome's survival rested on a single legendary incident of mass abduction

The legend of Romulus and Remus is one of the most popular stories of ancient Rome, and it basically describes the founding of Rome. According to a story that's inspired countless works of art, it was Romulus who gave the order to kidnap the women of a neighboring tribe to secure the foundations of the Roman population.

The Sabines were very real, and their historical story involves regular skirmishes with Rome and ultimately, assimilation: They were made a part of Rome in A.D. 268. The mythology is much darker and much more uncomfortable, starting with Romulus' decision to force Sabine families to allow their daughters to marry into Roman society. After they refused, Rome organized a massive festival that was really just an opportunity to get the Roman men near enough to the Sabine women to choose their future brides from among the crowd, then abduct them.

The women were forced into marriage, and the whole thing descended into outright war. Things got bad, but at the same time the Sabine men were fighting to get their daughters back, those daughters fell so deeply in love with their captors that they ultimately begged for the fighting to stop. Livy recounts (via World History) their plea: "Better for us to perish rather than live without one or the other of you, as widows or as orphans." That's... not a message that would be sent these days.

Tarpeia, a betrayal, and a place of executions

The story of Tarpeia is one that's wrapped up in the tale of the abduction of the Sabine women, and it's a tricky sort of story that says more about the person telling it than about Tarpeia herself. Tarpeia gives her name to the Tarpeian Rock, a site that's part of Rome's Capitoline Hill that was used for public executions. Still, there's a few different versions of Tarpeia's story, and that's the telling part.

The oldest version says that when the Sabines attacked Rome in an attempt to free their stolen women, Tarpeia made a deal with them: She would open the gates to Rome if she was rewarded with all that the attackers wore on their left arms. She hoped for jewelry and gold, but what she really got was buried beneath and killed by their shields, which they carried on their left arms. Historians say that in subsequent tellings, her sin was made even more grievous: In some, she's a Vestal Virgin. Either way, she's greedy, duplicitous, and conniving. Or... was she?

It was the famous historian Livy who wrote that original version of the story, and he actually suggested an alternate version that puts her in a different light: He says she wasn't interested in wealth at all, and staged the whole thing as a way to disarm the Sabine attackers. Or, did she open the gates as a Roman woman protesting against her own community's large-scale abduction and rape of a neighboring civilization?

Be good, children, or we'll definitely be sacrificing you at the next crossroads festival

While today's children might be threatened with being on Santa's naughty list or losing their phone privileges, there's evidence that, for a period in ancient Rome, children were threatened with the prospect of being sacrificed to household deities called Lares, because that was definitely a thing that happened. It was eventually outlawed and the lives of children were replaced with offerings of garlic and poppies, but for a time, the practice was part of a festival called Compitalia. It somewhat ironically honored spirits that were thought to represent both a family's ancestors-turned-guardian-spirits, as well as crossroads both literal and figurative.

Ancient texts suggest that it was usually male children who were sacrificed during the annual festival, but other sacrifices at other festivals to the Lares were no less brutal: In one, Ovid wrote of unborn calves being cut from their mothers and burned. Their ashes were thought to have protective properties, and were handed out to local families.

Pigs were also common sacrifices, but after the end of the practice of sacrificing human children, it seems as though there were still reminders. Festival decorations continued to include human figures, made from wood and hung at various, important locations. Why? As a substitute for real children. Sweet dreams!

[Featured image by Carole Raddato via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]