The Hidden Truth Of Christa McAuliffe

When you think about space travel, what comes to mind? Maybe it's all those big news stories that have been cropping up recently as private companies send the rich and famous into space. Maybe it's NASA missions, the storied history of human exploration, or the occasionally messed up things that happened during the Space Race. If it's the latter, then there are, of course, plenty of successes to reflect on, but also tragedies that deserve to be remembered in their entirety — including the worst part of Apollo 1, the hidden truth of the Challenger crew, and the final words of the Space Shuttle Columbia's crew, just to name a few.

And where the Challenger disaster is involved, then you'll probably hear the name Christa McAuliffe, as well. In short, McAuliffe was a teacher and the first civilian to go into space. The winner of the Teacher in Space Program, she was chosen from some 11,000 applicants from across the country and had plans to teach lessons from space.

Unfortunately, that never actually happened. The morning of January 28, 1986 proved to be an especially cold one, and the weather ultimately caused massive technical failures in the shuttle's O-rings. As the craft took off, it seemingly exploded in mid-air, killing all seven astronauts on board, McAuliffe included. The nation went into mourning, and memory of the Challenger crew has since lived on, but despite Christa McAuliffe becoming something of a national hero, there's probably still some information about her you don't necessarily know.

Christa McAuliffe's name was a source of confusion

In general, when you look up information about the Challenger disaster, you'll find that Christa McAuliffe is referred to as, well, exactly what you just read. However, in some situations, you'll see her referred to instead as "S. Christa McAuliffe," because, as it turns out, "Christa" isn't technically McAuliffe's first name.

To be clear, McAuliffe did go by the name "Christa," but when she was born, her parents faced a strange conundrum. As explained by McAuliffe's mother Grace George Corrigan in "A Journal for Christa," they decided that her middle name would be Christa, and her first name would be Sharon. They actually called her "Sheri Christa" and eventually decided that "Christa" just fit her a lot better; they essentially treated that as her first name from then on. McAuliffe herself didn't even fully realize that her first name wasn't technically "Christa" until she had to take a look at some of her legal documents, a realization that led to her signing official documents as "S. Christa Corrigan" (her maiden name).

Funnily enough, this little quirk led to a strange bit of confusion when the Teacher in Space Program rolled around. McAuliffe questioned whether she would be allowed to leave the "Sharon" out of her name, and thus left it in. As a result, Vice President George Bush announced that "Sharon McAuliffe" had earned the position, and many of McAuliffe's friends didn't even realize Bush had been talking about her.

Teaching wasn't always easy for her

Aside from the Challenger disaster, Christa McAuliffe is largely remembered for being a teacher. After being brought onto the project, she used her position to help advocate for the plight of teachers in the U.S., and she was clearly passionate about her work. Despite that, though, teaching wasn't always the most bearable profession for her.

McAuliffe's mother shared some of her conversations with her daughter in "A Journal for Christa," recalling that at one point, McAuliffe saw school as a "total waste of time as far as school work goes." Granted, she wasn't downplaying the importance of education, but rather, she was raging against the educational systems she had to fight against. More specifically, she was mostly expressing her anger about how little teaching she was able to do sometimes, as students were excused from class for testing or for school fundraisers, which meant she couldn't actually put any lessons together.

In much the same vein, she criticized the school's use of discipline. Not only were some of the kids unruly — at one point, she disclosed, "There are still a few I would like to string up" — but at the same time, the administration refused to offer any aid to teachers. She felt she was forced to enforce discipline after the administration suspended a student, despite knowing nothing about the reason behind the suspension. In short, she started feeling like she was there to do everything but teach.

She was asked to appear on an awards show

With the power of hindsight, it's very easy and understandable to say that Christa McAuliffe is something of a hero. It'd probably be pretty unlikely that anyone would argue against that point. At the time though? McAuliffe herself would have tried to dispute that point. In fact, at one point, she did just that.

As her mother recalled in "A Journal for Christa," McAuliffe was named one of CNN's heroes of the year in mid-1985. She wasn't exactly the biggest fan of that accolade, claiming that she hadn't really done anything yet or necessarily broken any barriers. Regardless, the title led to her being invited to present at the Emmy Awards for newscasters. Despite some hesitation, she eventually gave in and accepted, but the overall experience proved to be quite an interesting one. She and her friend got to ride there in a limo, but after being directed to the correct floor of the hotel in which the show was being hosted, she wasn't actually shown where to go. The two of them had to change in a bathroom, exiting to the curious expressions of celebrities as they came and went. Then, they had to find somewhere to keep their luggage; the best place ended up being under the hors d'oeuvres table.

And after the ceremony? The two friends got back in their limo and headed to McDonald's for soda and burgers with their driver. Certainly a unique experience.

McAuliffe wasn't exactly a favorite of the rest of the crew

The decision to send a civilian into space was a popular one with the wider public; having that civilian be the adventurous and personable Christa McAuliffe just made that decision even more perfect for the media. Despite the fact that McAuliffe was a hit with the public at large, the same couldn't be said of her reputation with the rest of the Challenger crew.

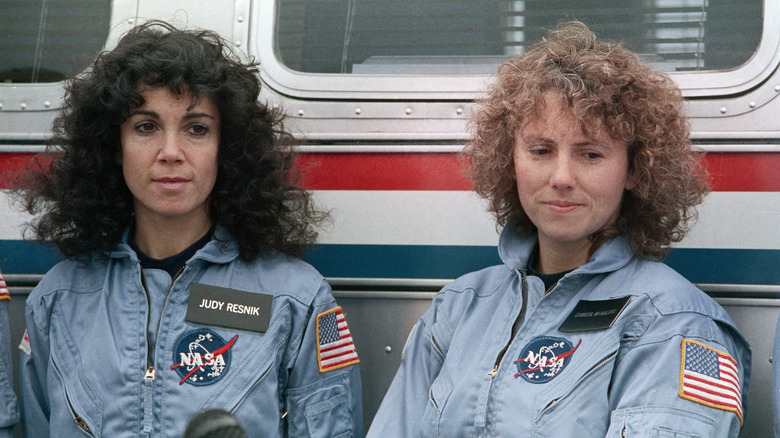

After all, the rest of the crew came from a very different background from McAuliffe — scientists, engineers, pilots, and the like. Upon hearing about the Teacher in Space Program, a lot of them were skeptical of the whole thing; most of them also had colleagues who had more technical qualifications for traveling in space. So for a teacher to take one of those precious spots on the shuttle — it didn't exactly sit well. Judith Resnik in particular disliked the whole affair, accusing NASA of selling out just for the media attention.

That said, the situation changed as time went on, and as the crew truly got to know McAuliffe. On one hand, they couldn't deny that the attention was, ultimately, a good thing for the longevity of the space program. And on the other, it was clear that McAuliffe had worked hard to get her spot, and was continuing to work hard to meet their standards. They couldn't continue to dislike her after that.

She dealt with fame with humility and grace

With Christa McAuliffe being a perfectly normal person suddenly thrust into the spotlight, it stands to reason that the fame would've been hard to deal with. After all, there are numerous examples of celebrity status going to a person's head.

But that wasn't the case with Christa McAuliffe. Not even close. Per "A Journal for Christa," plenty of reporters brought up the fact that she wasn't exactly a normal civilian anymore; she was something of a celebrity in her own right, and, as such, could have access to money or political status — anything she wanted, really. Her response? All she wanted was to go back to teaching. In her own words, "I didn't choose my career so I could get monetary rewards ... If the Teacher in Space doesn't return to the classroom, then something is wrong!"

And it wasn't just in discussions about her future career that McAuliffe showcased her humility. In fact, she often described her new life as being surprisingly similar to teaching or other aspects of her normal life. When people came up to ask for her autograph? She compared it to signing hall passes for her students, and it still surprised her that people would even want her signature. And when reporters asked her about her opinions on Challenger? It felt to her like a student coming up to her in a study hall for help with their homework.

Training wasn't all fun and games (except for when it was)

Astronaut training definitely doesn't doesn't seem like the easiest thing, and Christa McAuliffe's own experiences support that assumption pretty well. During her training, she spent a lot of time in planes accelerating at high speeds, such that she would end up experiencing forces up to five times the force of gravity. In her words: "You felt like you were melting into yourself, like the Wicked Witch of the West" (via "A Journal for Christa").

Despite that, McAuliffe undoubtedly had a really good time. During zero-g training — basically riding in a hollowed-out plane as it rose and fell, replicating the feeling of weightlessness — she and her substitute for the mission, Barbara Morgan, were initially planning to take the whole thing very seriously. Aside from getting used to the sensation, they would then test out some of the experiments that McAuliffe planned to run in space. But that seriousness didn't last all too long. As McAuliffe later said, "It was hard to stay serious. Leap frog? Why not? We figured kids would love to see that." The two did try to contain their excitement because there were actual NASA officials there alongside them, whom they figured probably wouldn't be as eager to play.

Well, they contained some of their excitement, at least. Both of them took time to pose in mid-air as if they were skydiving, and Morgan did actually hop over McAuliffe's shoulders, crying out, "The first leap frog in zero gravity!"

McAuliffe's death furthered mental health discussions

The Challenger disaster was a national tragedy that touched a bunch of people across the nation, especially given that Christa McAuliffe was, herself, a civilian. But the impact of her death went beyond the general tragedy felt by those who spectated Challenger's launch. After all, she was a teacher, and that fact meant that plenty of schools were showing this particular launch to their students.

Shortly after the disaster, a U.S. News and World report even came out addressing this fact, calling it "the first ever national trauma on children," a moniker that took due to concerns over kids having to deal with the grief involved with seeing a teacher killed. And while there were plenty of questionable things about Ronald Reagan's presidency, his choice to address this point explicitly in one of his own speeches wasn't one of them. But the concerns didn't stop there.

Full studies, including one published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, were done on children of varying age groups, examining their responses toward the Challenger disaster as they differed over time, and across various geographical locations. Without getting too lost in the details, the study found that children experienced the effects of trauma, even if they weren't directly involved with any of the astronauts on the Challenger crew. Those effects proved to persist over the weeks following the disaster, generally fading over the course of the next year, though in a few cases, some of those children exhibited enough symptoms to be officially diagnosed with PTSD.

She inspired her students

Maybe it isn't too much of a surprise to say that Christa McAuliffe was well liked by the students that she taught, but all the positive things that they had to say about her are worth remembering for the images that they painted of McAuliffe as a person.

In talking to Today, a handful of McAuliffe's students recalled what it was like to see the launch. A group of them were gathered in the cafeteria with some of the other teachers, cheering loudly, even as the shuttle began to break apart, believing it was just the rocket separating. It took them some time to fully process what was happening, trying to convince themselves that things were alright, then trying to keep believing that the astronauts might survive. As the truth dawned on them, the sad realization hit them: "She didn't get to teach those lessons she really wanted to teach us ... That's hard to swallow now, you know?" They would never get to see her again, and they would only have the memories of how "she made education real."

One of McAuliffe's goals with the mission was to help kids learn about space, but the other was to inspire kids to become teachers themselves, and on that front, she did succeed. Her former students interviewed by Today had all gone on to become teachers, and they still looked to her as their model on how to teach, bringing reality to lesson plans, much like she did.

She had her family with her until the end

In the most literal sense, this isn't all that surprising, really. After all, Christa McAuliffe's family had all flown out to Cape Canaveral to see the launch in person. Granted, her siblings couldn't actually stay for the launch due to it being delayed by a few days, but her husband, parents, kids, and even her son's classmates were all there to see her leave for space.

But in "A Journal for Christa," McAuliffe's mother recalled the personal effects that she had taken with her on the shuttle. There were a few of her own things — a Bob Dylan tape and Girl Scout pin, for example — but also various mementos from individual members of her family. There were pieces of jewelry from her husband, grandmother, and sister, as well as her daughter's gold crucifix. And, to top it all off, she also had a stuffed animal that belonged to her son — a frog that technically wasn't actually stuffed, because it wouldn't fit in her belongings otherwise.

Conversely, her family also continued to feel her presence, even after they knew that she was gone. McAuliffe had bought Teacher-in-Space necklaces for her siblings, and the family was taken to her dorm room, where they found her shoes and athletic gear still where she had left them just that morning.

Her mission was accomplished many years later

Challenger is remembered now for its tragedy, so it's understandable if you've never heard much about its actual intended mission. Had things gone smoothly, the crew would've deployed both a satellite and another piece of equipment meant to track Halley's Comet, and McAuliffe would've broadcast two 15-minute lessons, as well as a handful of other smaller experiments, showing just how different normal processes could be when carried out in space.

Of course, none of those things came to fruition. Or, at least, they didn't come to fruition for a couple decades. See, in the early 2000s, more teachers — including McAuliffe's substitute, Barbara Morgan — began entering NASA's space program and training to be fully fledged astronauts. Then, as 2017 rolled around, a very unique opportunity presented itself: Two educators, Joe Acaba and Ricky Arnold, would have back-to-back stints on the International Space Station. In other words, for nearly one whole academic year, there would be a teacher in space.

Taking advantage of this Year of Education on the Station, the two of them decided to also honor both Challenger and McAuliffe by revisiting her lost lessons. With some slight revisions to accommodate for the new location — highlighting the daily life of astronauts on the ISS instead of the space shuttle — they still managed to bring all of those lessons to life, demonstrating Newton's Laws, liquid behavior, and plenty of other concepts in space. It took nearly 30 years, but McAuliffe's goal of engaging with students from space was finally realized.