Messed Up Things You Didn't Know About The Spartans

In ancient times, the Greek city-state known as Sparta found great renown as a society of the toughest soldiers in the known world, with their entire lives laser-focused on developing an unstoppable military machine. In modern times, this reputation has stood firm, thanks in part to Frank Miller's graphic novel 300 and its even more popular movie adaptation by Zack Snyder. That movie had such an impact on popular culture that many Americans who slept through history class know the Spartans as a nation of glistening-chested warriors ready at any moment to kick someone in a pit and tell them what the name of their city is.

And while some of the better known depictions may be exaggerated or fully fictitious, the fact is that the Spartans were a real-for-real fully automated soldier factory that turned out some of the toughest dudes that ever lived, repelling the Persian Empire and then taking down Athens in the Peloponnesian War. The problem with this is that the type of society where 100% of the citizens are full-time soldiers is not actually a very pleasant place to live. Ancient Sparta was a place filled with slaves, public humiliation, and ritualized beatings. Here are just some of the most messed up things about Sparta.

Slaves were everywhere in Sparta

Ancient Sparta was an incredibly stratified society, with strict class divisions drawn along social, gender, and ethnic lines. At the top of the heap (well, below the two kings and various oligarchs) were full citizens — ethnically Spartan men who had completed a rigorous initiation ritual — followed by free non-citizens called perioikoi who were basically a merchant class, and at the very bottom were the helots, a state-owned serf class (with various subclasses for non-Spartans sprinkled in the hierarchy here and there).

Ethnically speaking, helots were most likely the indigenous people of Laconia and nearby Messenia, made into a slave race after being conquered by invading Dorian people. (The Dorians were Macedonian tribes from the north who conquered the Peloponnese; Spartan citizens were ethnically Dorian.) They were state-owned in that even though each helot would be assigned to work the land of a specific citizen, their master could not sell or free them even if he wanted to. Helots had no political or voting rights, though they were allowed to marry and had a limited right to own property after paying their master his share.

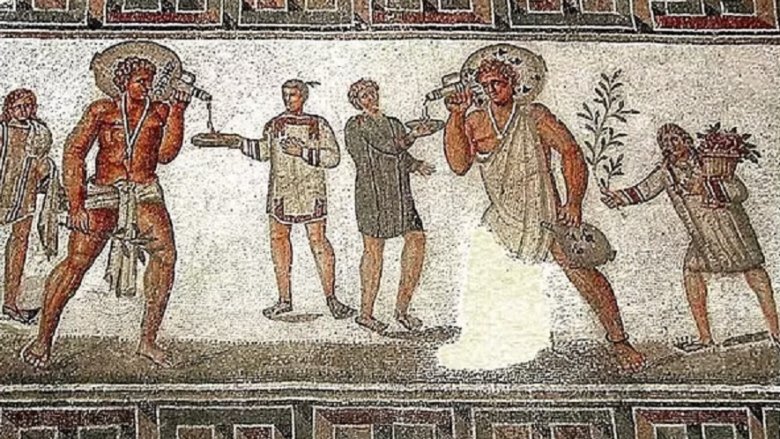

If you're wondering if this society renowned for its ruthlessness in battle was kind to its ethnic slave class, uh, no. According to the historian Plutarch, the Spartans treated the helots "harshly and cruelly," often force-feeding them wine and making them dance in public to teach children the dangers of drunkenness.

The Spartans' non-metaphorical class warfare

As is usually true in an aristocratic and oligarchic society, Spartan citizens were a minority class. While the proportion of Spartans to helots varied over time, according to the historian Herodotus, in the fifth century there were seven helots for every Spartan citizen at the Battle of Plataea. This imbalance in numbers meant that, naturally, the Spartans were terrified of the helots. It would not be an exaggeration to say that keeping the helot population in check was a major concern of the Spartan oligarchy and a central focus of much of their social legislation.

And the Spartan aristocrats were right to be afraid of potential uprisings; there were a number of attempted insurrections, including the plots of the general Pausanias (who was turned in by the very helots he was promising to free) and a failed uprising that tried to take advantage of the chaos brought on by a big earthquake in 464 B.C. In recounting one such failed insurrection, Xenophon says the underclasses of Sparta hated the upper class so much that they "would be glad to eat them raw."

Because of this very real (and deserved) fear of their perpetual underclass, the Spartans took severe measures to keep the helots subservient. In addition to public acts of humiliation, Plutarch says each autumn when the despotic ruling council known as the ephors took office, they formally declared war on the helots so Spartan citizens could kill them with impunity. Every year this happened.

Tales from the krypteia

Perhaps the most important tool the Spartans had for keeping the helot population in check was a sort of secret police called the krypteia, made up of young men undergoing the rigorous training necessary to become full citizens and hoping to prove their willingness to kill for the state, thereby earning higher military positions upon the completion of their training. So basically a super cool combination of the SS, the Hitler Youth, and, like, JROTC.

After the ephors declared war on the helots each fall, the young members of the krypteia would go out at night into the countryside with knives, looking for helots. Any helot they ran into they were instructed to kill, with special attention being paid to the strongest helots, in order to reduce the overall strength of the serf population. Additionally, they would prowl through the helot villages, spying on the slave population and seeking out evidence of unrest and possible rebellion. Any helot found to be fomenting revolt would be executed.

The members of the krypteia underwent even more brutal training measures than the standard Spartan, and their methods were the opposite of the regular army. They focused on stealth, working as small groups and individuals, and stalking the fringes of Spartan society rather than protecting the city proper. Any member of the krypteia who was discovered would be whipped, but those who made it through service in the krypteia would be rewarded with choice leadership positions in both the military and society.

The Spartans were all soldiers, all the time

The elite ruling class of full Spartan citizens were known as Spartiates, or Homoioi (meaning "those who are alike," as they each enjoyed equal status, similar to the English term "peerage"). The Spartiate elite, ethnically Doric men who had completed the brutal agoge training regimen, enjoyed quite a lot of privilege within Spartan society, not the least of which was total control of the government and exemption from all manual or commercial labor. All such work in markets or fields was carried out by perioikoi or helots.

The flip side of that coin, however, was that all Spartiates were full-time soldiers for life. Sparta was and is renowned for its dominant military force, and part of that came from its soldiers devoting literally their entire lives to military service. As young men undergoing the agoge, Spartiates were assigned to communal mess halls known as syssitia to which they were bound for life, living in barracks until they were too old to fight, only seeing their families when they were able to sneak away. Each Spartiate was assigned a plot of land and helots to work it, which provided the only source of income for each Spartan citizen. The bulk of that income went to pay dues for their membership in the mess halls. Military service started at age 20, full citizenship was obtained at 30, and participation in the army was expected until age 60, though Spartiates up to age 65 might be conscripted in an emergency.

Spartans definitely threw out the baby with the bathwater

The word agoge derives from the Greek word meaning "to lead" and can, depending on the context, mean "guidance," "training," or "child rearing." This strict course of training was required for every male Spartan citizen, with the exception of the first-born sons of the two ruling houses. The point of this rigorous — and incredibly cruel — regimen was to create brave, hardy, strong citizen soldiers who would defend their city no matter what. And the Spartans didn't mess around: agoge started at birth.

Immediately after birth, Spartan boys were bathed in wine, as they believed this would make the babies hardier. Then the child would be taken to the gerousia, the council of Spartan elders, for inspection. The elders would look the baby over to see if he could be deemed fit enough for the Spartan life. Any baby found unfit due to disability, deformity, or even just perceived weakness would be set out at the base of Mount Taygetus for days for a secondary test that only ended one of three ways: the baby survived and was welcomed back into Spartan life, some kindly stranger found the baby and rescued it, or ... well, you know what the third option is. It's hard to imagine the first two outcomes were that common.

Some babies might have preferred dying of exposure, as Spartan mothers were renowned for their "tough love" techniques, constantly bathing their infants in wine and intentionally ignoring their cries in hopes of toughening them up.

Are you stronger than a Spartan 5th grader?

Boys would leave their home at age 7 to begin their training in the agoge, leaving their families and basically becoming wards of the state. At this point the boys were put into their communal barracks where they would spend most of the rest of their lives. Here they were under the supervision of a paidonomos, or "boy-herder," whose job was to educate the boys in academics, sports, hunting, and — of course — warfare.

At age 12, boys would only be given a single piece of clothing a year: a red cloak called a Phoinikis (so-called due to the Phoenician-style red dye used), which they were required to wear at all times, regardless of season or weather. The boys were also intentionally underfed so they would become accustomed to the hunger and thirst that accompany the military rations on the battlefield. Additionally, the Spartans were, as you could guess, pretty serious body shamers who were not interested in fat soldiers. To further encourage bravery in the boys, however, they were actually encouraged to steal food to supplement their meager rations, under the proviso that they would be severely beaten if caught.

Other harsh conditions exacted on Spartan tweens included sleeping on beds made of reeds pulled from the river by hand, no knives allowed, and practicing sports while barefoot. Elders also encouraged fighting and bullying the weaker boys, with the idea that humiliation would inspire them to toughen up.

The picture is a metaphor

All right, let's address the elephant in the room: As with most Greek societies in the classical era, Sparta had a culture around relationships between youths and older men. The nature of these relationships among the Spartans is hard to define, and almost certainly changed over time. On the one hand, Plutarch reports that once boys hit puberty, they would catch the attention of "reputable young men" as well as "elderly men," who would come out to the places where the boys would exercise in order to observe the boys as they trained their bodies and minds, correcting those who made mistakes. In this regard, the older men's role was largely about correction and education, but there was definitely a physical aspect to it, as Plutarch and the Roman author Aelian using the word "lover" and "beloved" to describe the participants in these relationships.

On the flip side of this, the Greek author Xenophon emphasizes that among the Spartans, such relationships were not like those among the Boeotians, but rather were only tolerated if it was based on friendship and a genuine desire to better the younger partner. Any such association based purely on physical attraction was banned as an "abomination." That said, Plutarch's and Xenophon's interpretations are not mutually exclusive.

The Guardian, however, suggests that for the Spartans, the practice of these relationships may reach back to the primitive Dorians, where the ritual was definitely physical, with the intention of passing the virtues of manliness down to the younger partner. Pretty messed up no matter how you slice it.

Don't worry, Spartan women were mistreated, too

Boys weren't the only ones subjected to inhumane conditions while growing up. While it is true that girls were not meant to become warriors, they were still expected to give birth to warriors, which meant a pretty rigorous lifestyle for them, too. While compared to other Greek city-states, Spartan women enjoyed a much freer existence, it's important to understand that the liberties afforded to the women of Sparta were not for altruistic reasons, but because they were seen as the means by which Spartan society would advance.

It is true that Spartan girls were given a public education, including poetry, music, and warfare (unheard of elsewhere in Greece) and were allowed to practice athletics outdoors, unclothed, with boys (any of those three things would have made an Athenian pass out at the impropriety), but these things were done in order to make fit women who would give birth to fit babies. Girls and women were forbidden from wearing makeup or any other kind of beauty enhancement (though they were renowned for their natural beauty) and from using their education toward any kind of career. They earned money from their family's land holdings, like the men. Traditionally feminine traits like grace were spurned in favor of physical fitness and a strong sense of morality. Despite seeming more modern in many ways, the goal of this training was turning Sparta's girls into sleek and strong 24/7 baby-making machines, since, as the common saying went, "only Spartan women could give birth to men."

Sticks and stones, Sparta style

One aspect of life for Spartan women that would have been scandalous for any other Greek city-state was their ability to converse with men in public. In fact, Spartan women were renowned for being witty and sharp-tongued, able to drop politically savvy barbs at any moment. The idea behind this was that smart women would have babies who were as strong of mind as they were of body.

But Spartan girls were specifically trained in the skill of savage burns and were encouraged to practice them in order to further the betterment of the boys undergoing the agoge. They would publicly humiliate boys during their training, singling out the weaker ones who might be struggling among their peers. In fact, this hazing was often ritualized at public festivals, in which the girls would stand in chorus in front of the nobles of Sparta and sing songs about the abilities (or failings) of the boys. During this performance, they would dedicate verses to absolutely laying into any boy who was thought not to be up to snuff. Needless to say, the Spartans thought shame was a powerful motivator and incorporated it into a lot of their social structures, hoping that public embarrassment would chastise their citizens into stepping up their games.

Next time you feel embarrassed for making a mistake at work, just be relieved that a choir of teenage girls aren't standing in front of your boss laying down the most savage diss track about you they can muster.

Do you bite your Spartan thumb at me, sir?

In addition to strength and prowess in battle, wit was a highly prized virtue among the Spartans. In fact, even today, we use the phrases "laconic wit" or "laconic phrase" to represent the idea of inflicting the fiercest possible burn in the fewest words possible. (The word "Laconic" means "from Laconia," the region where Sparta was.) If you saw 300, you heard some examples of laconic wit, many from authentic sources, such as the Persian assertion that their arrows would blot out the Sun being answered by the Spartans, "Then we will fight in the shade."

Perhaps the most brutal example, however, was also the shortest. King Philip II of Macedon (father of Alexander the Great) had launched a huge campaign to basically conquer all of Greece. To encourage the Spartans to submit to his will, he sent ahead a message saying, "If I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." To which the Spartans gave a single-word reply: "If."

As super hardcore rad as that is, the fact is that this laconic wit wasn't natural talent; it was fiercely practiced and instilled into Spartans through training. As children, they would be asked questions, and if they didn't answer succinctly and wittily enough, their masters would bite their thumbs.

The beatings will continue until morale improves

It wasn't enough for Spartan society to see their boys tortured through verbal hazing, food deprivation, heartless living conditions, and having their fingers bitten. Naturally they also liked to see their young men physically beaten in a religious setting. This rite of flogging was at the heart of the diamastigosis, the primary attraction at the Festival of Whips, an annual ceremony carried out at the shrine of Orthia, a local Spartan hunting and fertility goddess later identified with Artemis.

According to Xenophon, the ritual began as basically a ceremonial game of capture the flag, but with cheese. Cheeses would be placed along the altar, and one group of youths would try to steal the cheese while another group defended the altar with whips. By the time of the Greek geographer Pausanias, however, the game element seems to have been dispensed with, with the only remaining competitive element being to see which boy could withstand the most whipping. A priestess would stand by the altar holding a wooden statue of Orthia, and if she perceived that any boy received too light a whipping due to bias or favoritism — because he was too handsome or because his family was too powerful, for example — she would claim that the statue was getting heavier and demanded more blood.

This was another ritual carried out to toughen Spartan boys up, but it also served as a form of spectator entertainment; by Roman times theaters were built specifically to watch the flogging of boys.