The Most Famous Student Protests In History

College is a time when young adults can strike out on their own, and sometimes, students don't just find their calling but their causes, too. When they get together to find their voices, it can shake the world: Interestingly, University of Minnesota professor and historian David M. Perry and Virginia Tech professor Matthew Gabriele say (via CNN) that student protests actually created the modern university.

It's a fascinating bit of history that took place in 12th and 13th-century Paris, at a time when education was pretty firmly connected to religion. Schools of higher learning were based in cathedrals, but in 1200, a group of students who had been ripped off by a Parisian shopkeeper decided they weren't going to stand for it and destroyed the shop in question. The conflict escalated into violence and several deaths, and the entire thing was taken before King Philip II Augustus of France.

He was the one who decided that teachers, students, and universities had rights, and it was an important precedent. In 1229, another conflict between students and a shopkeeper again escalated to violence, and it took two years and intervention from the pope before laws were put in place that granted universities independence to self-regulate. Those protests ended up laying the groundwork for modern universities, and it just goes to show just how powerful student protests can be. With that in mind, let's talk about other times students stepped up and took a stand.

Questions still remain about why a 10,000-student protest went terribly wrong in Mexico

The setting: Mexico, 1968. The Summer Olympics were going to kick off in a few days, and students took that opportunity to stage a peaceful protest in Mexico City, one that was guaranteed to reach the world stage. At the heart of the protest was a call for a change to the nearly 40 years of a single-party government, and just what happened then isn't entirely clear. On one hand are claims that the protest turned violent and was ended by a military who had no choice but to open fire, and on the other hand, there are plenty who say that wasn't the case at all: Then-President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz was accused of seeing an opportunity to make a statement that left-wing politics wasn't going to be tolerated.

On October 2, a gathering that included thousands of students from universities — including the National University and the National Polytechnic Institute — was winding down when the gunfire started. When the smoke cleared, two hours had passed, and to this day, no one's been able to figure out what happened.

Depending on the source, the death toll varies between four and 3,000. Reports of military snipers (around 360 of them) setting off the conflict have emerged as the most likely scenario, thanks to the release of long-buried official documents, but it's still unclear how many died, how many were arrested, and how many simply disappeared.

Continued gun violence means the March For Our Lives is still active

In 2018, Parkland, Florida's Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was the site of a school shooting that left 17 dead and another 17 injured. In the days after the shooting, students organized the March For Our Lives. In one of the initial protests, more than half a million people converged on Washington, DC, while more than 800 other events were held across the country.

Among the loudest voices in the campaign for stricter gun controls and a ban on assault weapons were Parkland survivors. Demands were succinctly summed up by survivor Cameron Kasky, who said (via NPR), "Politicians either represent the people or cannot. Stand for us or beware: The voters are coming." Another survivor, Emma Gonzalez, took center stage at the rally for 6 minutes and 20 seconds, the length of time that the gunman was active in her school. She added: "Fight for your lives before it's someone else's job."

The March For Our Lives has continued. In 2022, another rally was held in Washington, DC, with Parkland survivor and protest organizer David Hogg still at the forefront to remind people (via The Washington Post), "As we gather here, the next shooter is plotting his attack." Activists associated with the movement were still staging protests at state capitols in 2023, and is that too long to campaign for change? One speaker said (via CBS News), "Five years ago today, hundreds of thousands of people knew that they had had enough."

Greta Thunberg's Fridays for Future idea turned into a global movement

In 2018, then-15-year-old Greta Thunberg skipped school and headed to the Swedish parliament to try to raise awareness about climate change issues. It's safe to say that she succeeded in a big way. She started Fridays for Future the following month, and by November, students in 24 countries had joined her in striking from their schools on Fridays. By February of 2019, that had grown to 30 countries, and 135 countries by March.

While Thunberg has gone on to sue five countries, be wildly controversial, and gain the ire of countless politicians from around the world, millions of students continued to join her in climate change protests. Protests went way beyond being only student-led, with Amnesty International even helping to organize coordinated events in 2023, seeing millions of people calling on governments around the world to do something about the continued use of fossil fuels.

When EuroNews looked at the numbers and the impact in 2023, they noted that the student-led protests had gotten adults, professionals, and scientists involved for a reason summed up by Audra Balunde, the head of the Environmental Psychology Research Centre in Mykolas Romeris University: "My motives were very simple. I just wanted to support young people's efforts and to show what I stand for. It seemed the right thing to do." And it has made a difference, particularly in encouraging the development of programs and think tanks dedicated to finding new, more environmentally friendly technologies.

Pro-Palestine protests in 2024 led to numerous arrests

There's nothing simple or straightforward about the history of conflict between Israel and Palestine, and in 2024, the conflict made U.S. headlines when Congress questioned Columbia University's president amid reports of rampant antisemitism on the college campus. Pro-Palestine protests were making headlines as well, and on April 18, the New York City Police Department stepped in.

Around 100 people were arrested that day, and it caused shockwaves felt through college campuses across the country. Other student bodies set up similar protests, and it turned out that calling law enforcement did little to dissuade Columbia's protestors. Classes were made distance-only just a few days later, more students joined across the country, and deadlines calling for the end of Columbia's protests came and went while being largely ignored. Nationwide arrests continued along with nationwide protests, and by the beginning of May, students at Columbia had essentially taken over the campus' Hamilton Hall.

Columbia students' refusal to disband came with an insistence that their demands hadn't been met, and they weren't just protesting to make a statement or raise awareness. They were looking for several things, including amnesty for those who had already been disciplined and an end to financial support to Israel. Promises to lend aid to Gaza and increase financial transparency didn't cut it, leading to both increased involvement from law enforcement and more protests across the country.

Students led the protests that culminated in China's Tiananmen Square massacre

Although the Chinese government has never confirmed exactly what happened and how many unarmed protesters were killed during the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square, the mass demonstrations resulted in one of the most iconic photos of the decade, if not the century: Tank Man, a lone, still unidentified figure in a white shirt, faces down a row of tanks. He was eventually pulled out of the way, but it's estimated that as many as 10,000 were killed during the protests that have largely been wiped from China's history books.

Events started with the death of Hu Yaobang, a high-ranking member of the Chinese Communist Party who was known for his vocal support of turning the country away from Maoist doctrine, corruption, and a government overhaul. He died on April 15, 1989, and almost immediately, students began gathering in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to mourn, organize, and continue to call for the reforms that he had championed.

Those student-led protests spread, and by April 22, 100,000 students attended his memorial service before continuing their protests. They boycotted classes, gave speeches, held rallies, marches, and hunger strikes, and gained global attention — especially after a mass sit-in drew a crowd of an estimated 1.2 million people. Things came to a head when the government decided to call in military troops, and the firing started on June 3. By June 5, the military had taken control of the city, and according to the Chinese government's official story, 261 people were killed.

Vietnam War protests defined Kent State's history

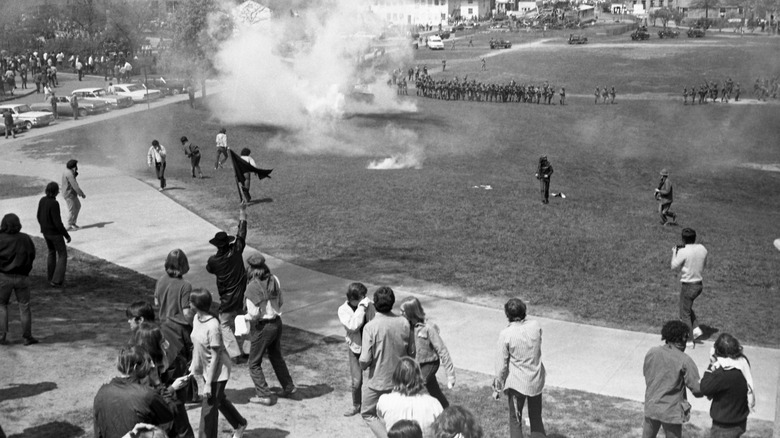

When then-President Richard Nixon ended April of 1970 with an announcement that the U.S. was going to be embarking on a joint invasion of Cambodia, there was massive outrage over what were widely perceived as broken promises of withdrawal from Vietnam. The 20,000-student Kent State quickly became a hotbed of protest activities, and it didn't take long for the National Guard to get involved: Kent's mayor put out the call on May 1.

Over the course of the next few days, students gathered, protested, set fires in garbage cans, and finally set fire to the ROTC building. Rumors circulated about dissident groups who were infiltrating student protestors to sow even more chaos, and the National Guard — armed with bayonets and tear gas — came into conflict with students. It wasn't until May 4 that armed Guardsmen opened fire on the students, wounding nine and killing four — including two who had only been walking to class.

The tragic incident had a domino effect that did, in fact, impact not only U.S. policies and involvement in Vietnam, but kicked off another series of events that would become the Watergate scandal. (Kent State also inspired Joe Walsh to become a musician.) In 2024, the Akron Beacon Journal spoke to one of the National Guardsman who had been there that fateful day, who said, "Dealing with the crowd's aggressive behavior was most stressful, but even with that, I find it hard to believe there was any intention to end this conflict as it so abruptly did."

Medical students protested the rise of the Nazis, and paid for it with their lives

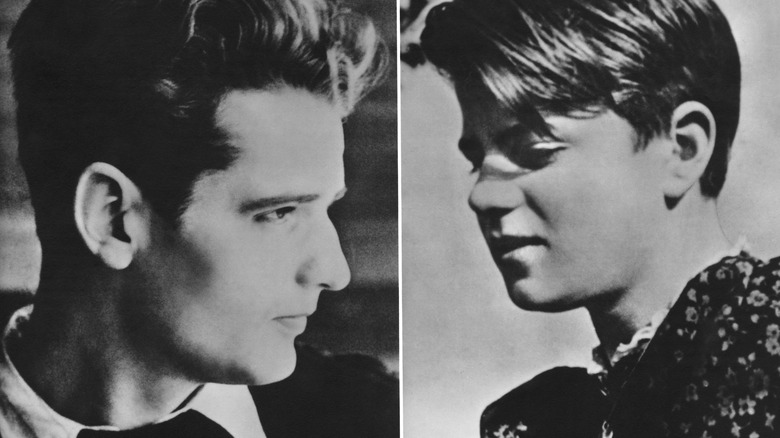

The heart of the student-led group that would become known as the White Rose were siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl (pictured), and their friends Willi Graf, Alexander Schmorell, and Christoph Probst. All attended the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich, and all — except Sophie Scholl — were medical students who got part of their education while being dispatched to the Eastern Front to serve as medics.

It was 1942, and when they returned, it was with a first-hand understanding of just how bad things were getting and what kinds of atrocities were being committed against Poland and Russia. By June of 1942, the students had organized into the White Rose, and started a campaign of distributing pamphlets, letters, leaflets, and literature to homes across Germany with the goal of mobilizing concerned citizens into a German-based resistance effort. By January of the following year, their underground resistance had grown into a sprawling network of protestors, while they continued to distribute their literature on campus and under an increasingly totalitarian regime.

On February 18, 1943, Sophie pushed a stake of fliers from an upper railing at the university, and was turned over to the Gestapo by a janitor who had seen and recognized her. Other key members of the group were also arrested — including Hans, Graf, Schmorell, Probst, and a professor named Kurt Huber. The Scholls and Probst were sentenced to death and executed on February 22. (Click here to read about others who stood up against the Nazi regime.)

Students spearheaded Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution

In 1989, Czechoslovakia was poised to end more than 40 years of Communism thanks to mass protests that may have been attended by people of all ages and walks of life, but that had been started by students. The timing was pretty perfect: The Berlin Wall had just fallen, democracy was tantalizingly near, and many had had enough of the government installed when the USSR rolled into a Czechoslovakia deemed too liberal for their liking and put an end to that.

Student protests happened almost immediately after Soviet interference with the 1969 self-immolation of a Prague student named Jan Palach. The Communist regime dragged on, though, and 20 years later — in January of 1989 — Prague celebrated a memorial Palach Week, dedicated to the fallen student. A few months later, they commemorated the slaughter of Prague students by Nazi Germany, and on that day — November 17 — students from all the major cities took to the streets and called for change.

And it absolutely worked. Communist leadership resigned 11 days later, after the students were joined by crowds that grew to half a million in Prague alone. A new government was installed on December 10, and the Velvet Revolution resulted in an elected president and a rebranding as the Czech Republic.

Four students kick-started a nationwide protest movement by simply sitting at a lunch counter

For anyone who thinks that just a few people don't stand a chance at kick-starting some widespread change, consider the Greensboro Four. Ezell Blair, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, and David Richmond were students at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University when they developed a plan: On February 1, 1960, they would stop at a local store, reach out to the media, then make some purchases at the Greensboro, North Carolina Woolworth's. Then, they would go to the lunch counter, sit, and ask to be served.

Word got out very quickly, and other students from other colleges joined in the protests, which spread to stores. Those who couldn't get a seat took to the picket lines, and it absolutely worked: Lunch counters began to be desegregated by the end of the month.

The student sit-in protests in Greensboro launched others, and the nonviolent protest launched by those four students is widely credited with helping to transform the civil rights movement. They demonstrated that peaceful civil disobedience could spearhead change, and Martin Luther King Jr wrote (via The King Institute), "The key significance of the student movement lies in the fact that from its inception, everywhere, it was combined direct action with non-violence. This quality has given it the extraordinary power and discipline which every thinking person observes." (For some perspective into the social climate of the time, check out this list of the worst crimes committed by the KKK.)

Students at UC Berkeley secured the right to freedom of speech

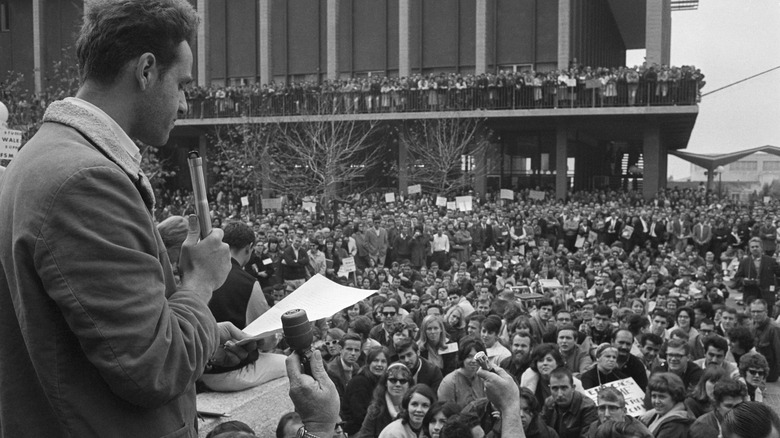

Today, UC Berkeley says that they consider freedom of speech to be one of the cornerstones of their campus beliefs, and that's not entirely surprising: In the 1960s, student protests kicked off a series of events that led to securing freedom of speech and the right to protest. It started on October 1, 1964, with a student named Jack Weinberg. He was arrested after setting up an information table on behalf of the Congress of Racial Equality, and it kicked off a 32-hour-long protest that involved hundreds of students and led to his release.

Protests didn't end there, and under the guidance of a philosophy major named Mario Savio (pictured), students continued to protest and continued to make it clear that they wanted assurance that their right to free speech was going to be respected on campus. Even before Weinberg's arrest, unrest had been brewing: The powers-that-be at Berkeley had established some major restrictions on what political activities and speeches would be allowed.

Savio lit a fire under the students with a speech — given from the roof of a police car — that condemned Berkeley's leaders as faceless manipulators. He said, "They're family men, you know, they have a job to do! Like Adolph Eichmann." Name-dropping one of the Nazis leaders definitely got attention, and the following protests not only set the stage for later protests against the Vietnam War, but newly-installed California governor Ronald Reagan started his run for the White House when he fired Clark Kerr — Savio's Eichmann.

Harvard's long history of protests goes back to 1766

In 1963, an anonymous writer penned a piece for The Harvard Crimson, writing that at the time, springtime came with the handing out of pamphlets that clarified, "The mere presence of a student at a disturbance or unauthorized demonstration makes him liable to disciplinary action." The writer went on to tell the tale of Harvard's first protest, and the Great Butter Rebellion became the first in a long tradition of student protests at American universities.

It was led by Asa Dunbar, and while his name might not be immediately recognizable, his grandson's name is: Henry David Thoreau. The issue? Being served rotten butter, and strangely, it was just the first in a long line of food-related protests that Harvard students made.

In 1768, protests over college food turned violent, and in the years around the Revolutionary War, once-violent protests were sort of put on hold for a bit ... except for that one time tea was brought into the dining room, and it didn't end well for anyone. Student protests led to the resignation of Harvard's president in 1780, and another food-related protest in 1807 led to the first time the entire student body of Harvard convened in the same place and time. The protest — dubbed the Cabbage Rebellion — had little impact, but Harvard's long-standing tradition of rebellious protests continued.