Messed Up Things That Happened In Pre-Modern China

The great French philosopher Volatire once wrote, "One need not be obsessed with the merits of the Chinese to recognise that their empire is the best that the world has ever seen." For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, that was the view basically everyone in Europe took. The meritocracy of Chinese civil service fascinated liberals, while Chinese art was considered so perfect that Asian motifs started to appear in the work of a generation of painters. Add to that tea, hanfu (Chinese-style kimonos), and magnificent palaces, and it's no wonder Imperial China appeared a utopia.

Except, you know how a literal translation of "utopia" is "no place," thereby mocking the very idea of a perfect society? Those Enlightenment Europeans should have paid heed to their classical education. Far from being a place of calm before the tsunami of the 20th century, pre-modern China was a place so messed up it would have given H.P. Lovecraft nightmares.

The Taiping Rebellion killed a lot of people

Pop quiz: What's the deadliest conflict in human history? The official answer is WWII. With between 60 million and 85 million deaths, no other war has even come close. Unless, that is, you include the upper estimates for the Taiping Rebellion. An insurrection that exploded in southern China in 1850, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, it lasted 14 years and saw over 600 cities utterly destroyed. While accurate numbers are impossible to find, the lowest death toll is generally considered to be around 20 million. The highest? 100 million dead (via Medium).

To be clear, the 100 million figure is probably a gross overestimate. Most historians tend to think "only" between 20 and 30 million were killed. To put that "only" in perspective, that's more than died in the entirety of WWI (appx. 8.5 million), the Napoleonic Wars (anywhere from one to 2.5 million), and the U.S. Civil War (less than one million) combined. And this was in a time and place that lacked pre-modern weapons. The killing done in the Taiping Rebellion was largely hand to hand. Even so, the 3rd battle of Nanjing in the rebellion's last days was likely "the largest battle in history until [World War I]" (per Medium).

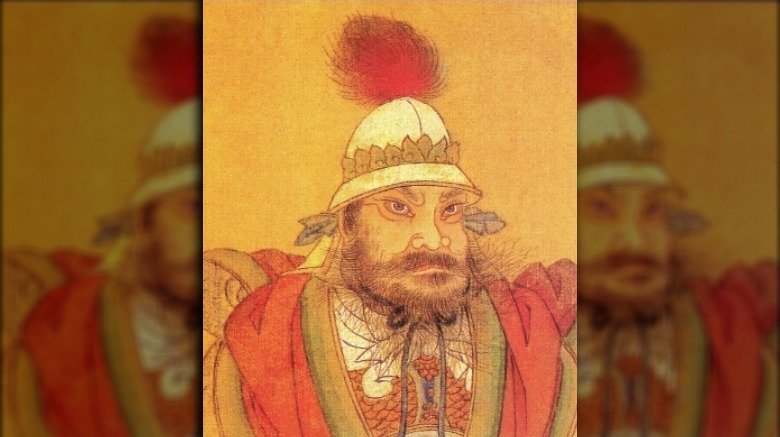

So what was the Taiping Rebellion? Well, it sparked when a teacher named Hong Xiuquan (above) declared himself the son of God and attempted to build a Christian theocracy in Qing China. Y'know, as you do.

A european superpower turned the Chinese into drug addicts

The Opium Wars are just one of those things from history that probably seemed like a great idea at the time, but are now super embarrassing to everyone involved. Taking place from 1839-42 and again from 1856-60, the two Opium Wars pitted first the British, and then the French against the might of Qing Imperial China. At the time, the Europeans had all sorts of justifications involving stuff like free trade and protecting missionaries, but you just have to look at the names to know what the wars were really all about. Britain was fighting for the right to flood China with addictive drugs.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation has the details: Britain in the 19th century was at the forefront of the opium trade, and getting all those sweet narcotics into the untapped Chinese market was seen as good business. So they started engineering 19th century China's own opioid crisis, and, when the Qing protested, they went to war. The slaughter the Qing endured in the First Opium War was so bad it helped spark the Taiping Rebellion, so ... nice work, Britain?

It also led to a huge increase in addiction. By the 1850s, opium addiction was so widespread in China that it threatened to bring the entire empire crashing down. Eventually, it did. The implosion of imperial China in the early 20th century can all be traced back to the Opium Wars.

An exam out of Kafka

One of the reasons Europeans really dug Imperial China was because of its civil service exam. At the time, entering the government on merit in Europe wasn't really a thing, and here was China, allowing anyone with the brains and talent to join. But while that probably seemed a paradise to a Frenchman living under Louis XVI, the reality was that Imperial China's civil service entrance exam was designed to be soul crushing. The BBC's In Our Time series describes a pass rate of less than one percent, with resits only available every few years. Because so many hopes were wrapped up in passing, the process sent many men mad.

Passing the entrance exam could bring honor not just on you, but on your entire village. Whole communities often clubbed together to raise the cash needed to have one of their members take the exam. This created a huge mental strain for the chosen ones, and entire lives could be spent revising and revising away, only for death himself to stamp your paper with the ultimate F. Chinese literature of the period is full of characters wasting away and driven to insanity by the demands of the exam.

The whole thing was also monumentally useless. By the Qing dynasty, Britannica notes that the exam was no longer based on merit, but on who could recite Confucius perfectly, and in a specific style. Yet it wasn't phased out until 1905, just before the entire imperial system collapsed.

Famines are serious business in China

You've heard of the Donner Party, America's most infamous tale of cannibalism in desperate times. Well, buckle up, because those frozen pioneers had nothing on what happened to the people of Anqing in 1861. In the depths of the Taiping Rebellion, Qing forces surrounded and cut off supplies to the rebel-held city of Anqing. After a grueling two year siege, the Qing army penetrated the walls. What they found inside could provide material for a dozen horror movies.

According to Cambridge University's history blog, the Qing didn't just uncover evidence that the starving citizens had resorted to cannibalism. They uncovered evidence that an entire economy focused around the sale and consumption of human flesh had grown up. Records were unearthed listing the market rate for a dead person, with a kilogram of human meat going for the equivalent of 50 pence (or roughly 2.2 pounds for .64 cents in U.S. equivalent).

Not that we have any eyewitness accounts of any of this. As author Stephen R. Platt describes in his book Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War, the Qing ended the siege of Anqing by beheading its entire 8,000-man battalion following their surrender. As for the civilians, per Cambridge, "more than 10,000 women were carried off by Qing soldiers as booty, sparing perhaps only some of the children."

The Ming Dynasty falls with one heck of a crash

They say all great political careers are doomed to end in failure. In pre-modern China, they were doomed to end in not just failure, but insurrection, rebellion, and the massacre of everyone you held dear. Take the fall of the Ming Dynasty. The guys responsible for the modern version of the Great Wall you're familiar with, the Ming, ruled from 1368 to 1644. When they finally fell from power, they hit the ground with an unbelievable crash.

ThoughtCo has the details: In the mid-17th century, a perfect storm of weak government and catastrophic famine led the peasants to rebel under the banner of the self-proclaimed Shun Emperor. The Shun Emperor conquered Beijing in a bloody uprising, causing the last Ming Emperor to hang himself in the Imperial Gardens rather than be captured. But rather than submit to the new Shun Dynasty, the surviving Ming loyalists decided they'd rather just burn down everything. So a general called Wu rode north to the Ming's one-time mortal enemies, the Manchus. He then promised the Manchu Qing that they could have China so long as they destroyed the Shun.

Destroy they did. The Qing conquest of China was an annihilating, apocalyptic war. Business Insider reports that around 25 million people are thought to have died. When the dust cleared, the Shun were dead, the Ming ancient history, and the Qing firmly in control.

The coup that killed millions

Ho, boy. Another Chinese uprising that killed millions. Did ancient China ever, like, do a non horrific rebellion? Probably not, but that doesn't mean the An Lushan rebellion isn't worth hearing about.

The dynasty in the firing line this time around was the Tang, the family that oversaw the golden age of Chinese culture, starting in 618 AD (via History). But that didn't mean they were always popular! In the early 750s, the empire was getting squeezed from all sides by enemy armies. Desperate to stay in power, the Tang emperor Xuanzong gave his best general, a shady looking guy called An Lushan (above), all the men and arms he could possibly need. An Lushan took one look at the giant army he now controlled and decided he could probably make a better emperor than old Xuanzong.

ThoughtCo has the details: In 755, An Lushan rebelled. He captured both Tang capitals and declared himself the Yan Emperor. Oh, plus he killed, like, tons of people (via BBC's In Our Time), but that's just politics, right? Sadly for An, his winning streak couldn't last. In 761, he was murdered by his own son, who was in turn assassinated, sending the Yan Empire into chaos, and letting the Tang retake control in a bloody war. But the fight doomed the Tang, too. The rebellion weakened them so much that they never fully regained their strength, eventually collapsing in 907.

China's other Great Famine

The 20th century was just an awful time to live in China. Between 1958 and 1961, the worst famine in recorded history killed somewhere between 36 million and 45 million people, according to the Guardian. Rightly known as the Great Famine, the "Three Years of Difficulties" is probably the grimmest legacy of the Mao years. But few people in the West know that it wasn't an isolated incident. 80 years earlier, Imperial China was caught in the grip of what's now called the Great Northern Famine. It was nearly as horrific as it's more famous cousin.

If the Great Famine can be likened to WWII, then the North China Famine was like WWI: less deadly overall, but still displaying a scale of suffering otherwise unseen in human history. Things officially kicked off in 1876 when a drought crippled the northern provinces, but, really, they started much earlier. According to the World Peace Foundation, "famine was preceded by periods of colonial conflict with Japan, England and Russia," as well as various internal conflicts, which led authorities "to allocate scarce resources to the construction of coastal defences rather than famine relief."

This diversion of resources contributed to a three year famine that killed between 9 and 13 million people. Less than Mao's famine, maybe, but still. Jeez.

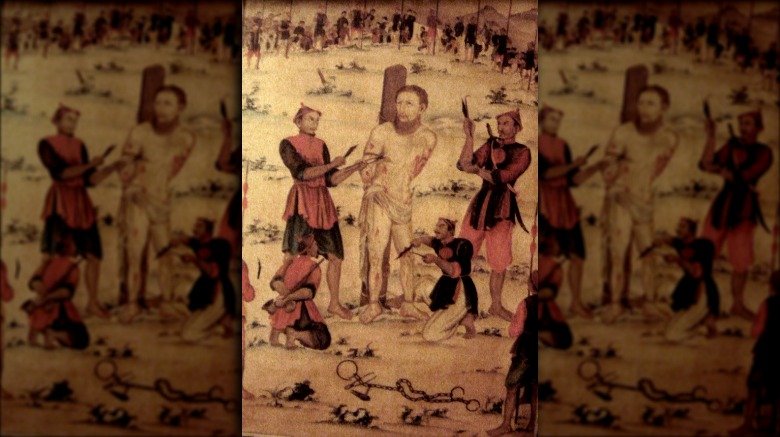

Death by a thousand cuts ended way later than you'll feel comfortable with

Death by a thousand cuts is one of the few things about ancient China that everyone in the West knows. Never mind that it was only reserved for the worst criminals and rarely used, the idea of having parts of your body sliced away until you die is so haunting you could stick a set of rails through it, call it a ghost train, and charge people entry. First practiced in the 10th century, it occupies the same ground in our consciousness as Europe's medieval tortures, one mostly based around feelings of gratitude that we live centuries away from it.

Well, here's the thing. Although death by a thousand cuts (or, to give it it's proper name, lingchi) sure sounds like something Vlad the Impaler would get his kicks with, it didn't actually go out of fashion until closer to our own time. How close? Try the year 1905.

The Harvard University Press book Death by a Thousand Cuts lays out the process of lingchi in full graphic detail, should you choose to read the the account of Wang Weiqin's execution in 1904. He was convicted of murdering 12 members of the same family, paraded through Beijing, and sliced to death in a vegetable market. While horrific, his death wasn't the last lingchi execution — an honor held by "a Manchu servant, Fuzhuli" who was carved up on April 9, 1905.

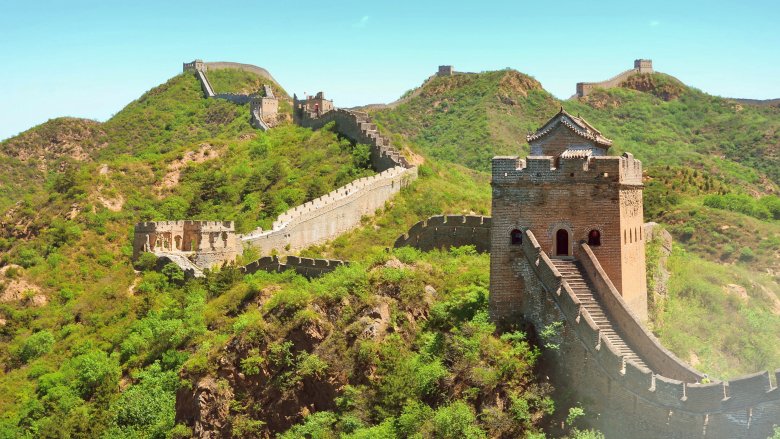

The Great Wall of Death

Ah, The Great Wall of China! A monument most of us know only via misconceptions about it being visible from space or being only a single wall. For example, did you know the current form only dates to the Ming dynasty? Oh, we mentioned it elsewhere in this article? Pfft, fine. Well, how about this fun fact then, kids. The Great Wall of China's original foundations were less mud or clay or bricks than they were misery and death. History estimates that 400,000 laborers were killed building the darn thing, with many of their bodies winding up in the wall itself.

That's a lot of corpses, and it gets even worse when you understand the context. Back in 221 BC, when the wall was started, there wasn't exactly a spare labor force hanging around, waiting for the order to build a 3,000 mile wall. So the Qin Emperor forced members of the general population into doing the hard work for him. The BBC's In Our Time describes how farmers were rounded up from all over China, dragged to the wall, and basically told to just get on with it. Contemporary Chinese poems record the construction less as an engineering triumph, and more as a national tragedy on a par with a great famine or war. Kinda takes all the charm out those romantic tourist photos, doesn't it?

The Heavenly Kingdom isn't so heavenly after all

After they seized control of Nanjing in 1853, the Taiping rebels declared a new nation called the Heavenly Kingdom. The idea was to build a society in China based on a strict interpretation of the Bible. You better believe that went about as well as ISIS's attempts to build an Islamic state 150 years later.

The Heavenly Kingdom managed to be both absurd and terrifying in its interpretation of scripture. Sexual contact was forbidden between men and women under pain of death, even if they were married. At the same time, Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan lived in an elaborate palace staffed entirely by women, and spent all his spare time engaging in elaborate orgies (via BBC's In Our Time).

Hong and other members of the leadership within his autocratic rule often decided policy in religious trances, which was used to justify all kinds of atrocities. But the worst came at the fall of Nanjing in 1864. Faced with a marauding Qing army, the Taiping committed mass suicide, setting themselves on fire, according to History. When the Qing entered the city, they killed all the survivors. All told, around 100,000 people died in three days.

The clothing police are actually real

Man, doesn't it suck how your boss is always telling you to, like, put some pants on before coming to work? What is he, the clothing police? Well, if your boss was living in Imperial China, that was a job he could totally apply for. After the Qing Dynasty conquered the Ming in the 17th century, they forced some bizarre clothing rules on the ethnic Han population. Of course death was the penalty for breaking the clothing laws! Did you even have to ask?

Those images you have of pre-20th century Chinese dress likely come from the Qing Dynasty. There are long lists available on dedicated history sites. Women had to wear clothes that would show at a glance their husband's social rank, lest anyone mistake them for a higher class and actually be nice to them. Not that the Manchu Qing were all awful where women were concerned. They actually tried to ban footbinding (via Smithsonian), but the Han Chinese refused to obey. Priorities, guys?

The most iconic rule the Qing enforced was the queue (above). A single long braid men were forced to wear their hair in, cutting it could result in on the spot execution (via China Heritage Quarterly). One of the reasons the death toll in the Taiping Rebellion was so high was because Qing forces could easily spot the rebels — they were the only ones not wearing a queue.

Fed up with eunuchs? Start a war!

Of all the reasons to spark a mass rebellion and overthrow a dynasty, the conduct of eunuchs has to be pretty far down the list. Yet that's exactly what happened in China in 184 AD. During the last century of the Eastern Han Dynasty, rumors began to swirl that a group of court eunuchs was corrupting the emperor. So, an end times Taoist sect formed, and rose up in a rebellion that took twenty years to quash, and wound up kicking the foundations out from under the Han Dynasty.

ThoughtCo has the details: The group that rose up under Taoist preacher Zhang Jue came to be known as the Yellow Turbans. Originally a cult, they soon transformed themselves into an armed force, and began attacking and wiping out entire towns. Caught on the back foot, the Han executed every civilian linked to the sect they found in their territory, before launching a counterattack that totally failed to end the uprising. Although Zhang and other leaders died in the first year, the Yellow Turbans remained so strong that the Han had to start arming warlords.

Although the Yellow Turbans were eventually put down, those warlords would go on to break apart the united China, eliminating the Han and plunging China into its Three Kingdom's war. Guess what? That war also killed tens of millions. Oh, China.