Bizarre Things You Can Only Find In Japan

Japan is known for a lot of wonderful things. There are the beautiful cherry blossoms in the spring, majestic Mount Fuji, and a royal family whose illustrious lineage stretches back thousands of years. But then there are the other things. The weird things. The rumors that are so bizarre you kind of wonder if they are true or not. Usually they do turn out to be true, because Japan has taken weirdness and made it a national pastime.

That means Japan has a lot of crazy things you can't find in other countries. Sure, now that the world is so connected, sometimes the weirdness seeps out a little bit, but in general, Japan is home to plenty of bizarre things that only show up there. Just walking down a regular street can be a voyage of discovery into the weird and wonderful. Here are some of the very esoteric things you can find almost exclusively in Japan.

Stores where you can buy human contact

The Japanese are in the middle of a love drought. Young people in particular have become more prone to celibacy, and say finding relationships is "too much trouble," according to The Telegraph. But it's human nature to seek affection, so in 2012 a brand-new type of business opened in Tokyo's electronics district. Soineya, according to Japan Today, was the first-ever "sleep together shop." Yep, that's monetized physical affection.

But not like that. The whole thing was much more innocent, as the store's webpage described the service as: "the simple and ultimate comfort of sleeping together with someone." Like, literally sleeping. For a few thousand yen, customers (okay, male customers) could sleep in bed with a beautiful woman. He could shell out more money for extras, like putting his head on her lap, petting her hair, or staring at each other. The kinkiest things on offer were a foot massage or the woman changing clothes (presumably not in front of the customer).

The service was apparently "quite popular," according to Japan Info, and by 2019 there were more cuddle cafes. Seen as a legitimate stress-reliever for office workers, the service even became equal opportunity. At the Rose Group, women can "rent" men for a quick two-hour nap, all the way up to a full 48-hour boyfriend rental (as long as you don't expect any intimate contact with your fake boyfriend). These cuddle cafes won't help Japan's plummeting birth rate, but at least people are getting a bit of human contact.

The suggestive Kanamara Matsuri festival

Shinto is Japan's original, nature-worshiping religion. And whenever you get belief systems that are in tune with the natural world, there will be fertility festivals. Shinto's is Kanamara Matsuri, and it's centered around a town just outside Tokyo. The festival originated from a legend of a demon that hid in a woman's privates and bit off anything that went inside. This was a problem for the woman's various husbands. Finally, a blacksmith made a steel member, the demon broke its teeth, and the blacksmith and the woman lived happily ever after. The town's Shinto shrine celebrated this tale with a large representation of the steel tallywhacker, and over the centuries people with STDs or fertility problems would come ask it for help.

The tradition saw a decline in the late 19th century, but a priest brought the festival back in the 1970s. It was a relatively tiny gathering for decades, but now it draws more than 50,000 people every April. Many of them are foreigners, there to enjoy the sight of statues of giant male genitalia being paraded through the streets. There are vendors selling absolutely everything shaped like, well, you know, from candles to hats to vegetables. It's attended by grandmothers, children, and crossdressers. The festival is marketed as LGBTQ-positive and non-discriminatory, as well as still holding some religious significance. These days, the money raised helps to fund HIV research. But more than anything, it's a party celebrating the peen.

Vending machines that sell absolutely everything

Japan is absolutely chock-full of vending machines. According to Tech In Asia, as of 2014, there were 3.8 million "automatic sales" machines in the country, or about one for every 33 citizens. That number doesn't even include slight variations on the vending machine, like change dispensers or those ones that spit out toys in the little plastic bubbles.

Vending machines in Japan sell a huge range of stuff, including newspapers, hygiene products, and drinks. But even those normal categories manage to shock international tourists, since beer and sake can be purchased just like you would a soda.

However, the most infamous Japanese vending machine offering is a lot crazier than that. Also not included in the official numbers are machines that sell young women's underwear. Used underwear. While this sounds too out-there even for Japan, Snopes claims it's true. Other sources say the "used" label was a marketing gimmick, and the underwear sold in the machines was just manufactured to look like it had been worn.

The machines seem to have disappeared around 1993. There had been a huge outcry against them, but they weren't breaking any laws. Obviously, no one had foreseen anything so gross. Finally, some businessmen were charged with selling antiques without a license (the idea being the underwear qualified since it was second-hand), and the machines allegedly went away. Some claim that if you go looking for them in Japan today, you can still find them in seedy areas.

A serious mayonnaise obsession

Mayonnaise went mainstream in Japan in 1925. Toichiro Nakashima lived in the United States for a bit and decided the way to make young people in his country grow as tall as those in the West was to get them to eat mayo. He mixed up the recipe a bit, adding more eggs and some apple vinegar for a sweeter taste. Then he started the Kewpie Corporation, and Japanese mayonnaise was born. It became an absolute obsession in the country.

It took some work, though. Since the Japanese usually ate cooked or preserved vegetables that weren't conducive to being dipped in mayo, Kewpie was marketed as more of a seafood condiment. From there, it started showing up as a regular ingredient in just about everything. Sora News 24 says the Japanese rarely sit down to a meal without a mayonnaise-based dish on the table. You'll find it on meat, noodles, and sushi. Cakes can have mayo in the batter, the icing, or both. Pizza is regularly doused in mayonnaise, with it included as a standard topping on most Domino's offerings. It gets even weirder, with mayo-flavored potato chips and ice cream, and even mayonnaise-rimmed margaritas. It's such a beloved condiment, numerous restaurants are themed around the ingredient.

The distinct mayo is cited as one of the foods most missed by expats, and visitors to Japan often fall in love and bring bottles of the stuff back home with them.

Iconic elevator girls in department stores

In 1929, a department store in Tokyo reopened after an extensive renovation. According to the anthropology blog Savage Minds, new features meant to tempt shoppers through the doors included air conditioning, a post office, and pretty young women running the elevators. The latter became iconic.

Is Japan Cool? reports the store's elevators were originally run by men, but the job quickly became one of the most coveted for Japanese women, which is not surprising considering their limited career prospects in general. It didn't matter where in the country they came from, because they were all taught an "intentionally fake," high-pitched way of speaking in the standard Tokyo dialect. While foreigners often find their voices annoying, they're meant to carry easily through a loud, crowded store, as well as be a clear indication that while they might be young, pretty, and trapped in an elevator with you, they are not there to be chatted up.

More stores added elevator girls, although today they are an "endangered species." Guidable lists only four Japanese department stores that still employed them in 2018. The women wear smart uniforms with hats and gloves, push the floor buttons for customers, make sure no one gets trapped in the doors, and answer any visitor questions. They often show up in various media like films, cartoons, comics, and even a popular 2006 McDonald's commercial. The elevator girls are considered an important part of Japan's tradition of hospitality, and a piece of cultural history worth saving.

A culture that encourages sleeping on the job

Japan was in the middle of an economic boom in the 1980s. They became proud of how hard they worked, with one ad slogan from the time extolling the virtues of working for 24 hours straight. That bubble may have burst, but the attitude of working yourself into the ground is still there. Somewhat counterintuitively, this means workers want to be seen sleeping on the job.

Inemuri, or "sleeping while present," has been practiced in Japan for at least a thousand years. The idea is you're working so hard, you absolutely must nap. The Japanese also consider it a form of multitasking, so you still get credit for attending a meeting even if you fall asleep in it. You're showing commitment to what's important, rather than leaving just because you need 40 winks. Not sleeping at work could even make you look bad. Your boss might encourage quick naps, or you might fake it just to be seen sleeping when you aren't tired, because it means you are pushing yourself like crazy.

People sleep in public as well (Japan's low crime rate means they are unlikely to be robbed), but there are rules. Manspreading is a no-no, as you should always try to nap in a compact position so you're not disturbing others. Women are also expected to avoid sleeping in an "unbecoming" position, because sexism is ridiculous.

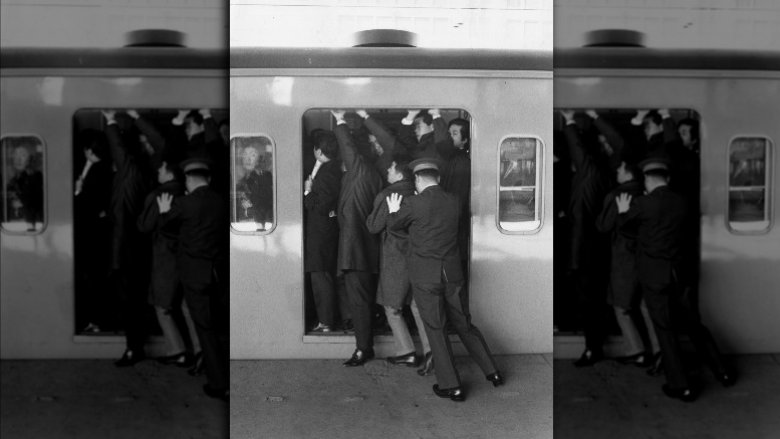

Pushers shoving commuters into packed trains

The trains in Japan are a big deal. Their technology is some of the most advanced in the world, and millions of people take advantage of it. They are also disturbingly punctual. NPR reports in 2018, a company offered an official apology when one of their trains left 25 seconds early, saying, "The great inconvenience we placed upon our customers was truly inexcusable." And if a train is ever delayed, commuters are given a certificate to present to their boss, explaining it wasn't their fault they were a whopping five minutes late to work.

This emphasis on punctuality means the trains absolutely cannot wait around while stragglers slowly work their way into a carriage. In Tokyo especially, trains and subway lines are jam-packed during rush hour, and with so many people looking to get to work or school, they sometimes need a bit of help boarding the train. Thankfully, polite, white-gloved "oshiya" are there to assist. When a carriage is already full to bursting and the last couple people on the platform are having trouble getting on, the oshiya come along and shove them in as hard as they can.

Also known as "pushers," for obvious reasons, these helpers are legitimate employees just trying to help. If the crush is so bad that one pusher isn't enough, another couple will come along to assist. It's a surreal but effective solution to the overcrowding problem, and allows all trains to depart on time.

Beer cans for the visually impaired

Unlike America, where basically the only drinks sold in cans are beer and soda, Japan loves to throw any beverage into aluminum. (This makes it easier to sell in the ubiquitous vending machines, after all.) There are canned juices, every type of coffee you can think of, and even more esoteric stuff. This isn't an issue if you have the use of your sight, but if you are blind, suddenly you have eight different types of canned drinks in your fridge and no way to tell them apart. In the morning, when you are all groggy and reach for a canned coffee, you don't want to make a mistake and end up with a mouthful of refreshing, but decidedly inopportune, beer.

In an attempt to be more accessible to the visually impaired, Japan's beer brewers recognized the problem and decided to do something about it. That solution was a Braille warning on the top of the cans indicating that they contain alcohol. While all the cans have something, there's no uniformity: Some say "beer," others say "alcohol," and a couple just have the brand name.

In a country where many individuals have a genetic allergy to booze, known as an "alcohol flush reaction," the ability to know what they're drinking before they take a swig can actually stop blind people getting sick, or at least uncomfortable, so it's extremely helpful.

Linguistically confusing blue traffic lights

In virtually every country in the world, there is a very simple constant on the road. It doesn't matter if you are driving on the right or the left: When you get to traffic lights, red means stop, and green means go. But in Japan, you'll see lights with a distinctly bluish tinge. If you ask what color they are, you'll find out the Japanese called them "ao," which literally means blue.

This comes down to a weird issue with the Japanese language. Originally, they only had words for four colors: blue, black, red, and white. Everything we'd consider green was covered by their word for blue. A distinct term for green is a "new" addition to the language, showing up around A.D. 794-1185. This means there's a holdover for calling green things blue, like Granny Smith apples. When green traffic lights showed up in Japan in the 1930s, everyone started calling them blue.

Over time, this became a problem. Linguists were driven to distraction by the incorrect usage, and it was confusing to international drivers. The Japanese faced pressure to start calling green lights green just like everyone else in the world. But instead of changing their language, they changed the color of the traffic lights. A law passed in 1973 said that all traffic lights had to be "the bluest shade of green possible," according to Atlas Obscura. That way calling them blue is technically accurate and no one can get mad.

Fruit that costs more than a car

American supermarkets are overflowing with cheap fresh fruit, which most people still don't manage to eat the recommended amount of. But in Japan, fruit isn't taken for granted like that.

The Japanese see fruit as a special treat. The history of Buddhists in the country leaving gifts of fruit for the gods means it's treated with respect, and fruit is also considered an important part of human-to-human gift-giving. That's not as miserly as it sounds, because in Japan even basic fruits are stupidly expensive. It can get so pricey, families will often split a single fruit between everyone, rather than each having their own.

But their love has gotten a bit out of hand. Bruised or oddly shaped fruit never makes it to Japanese supermarket shelves. As if that's not enough, high-end fruit stores sell luxury produce, where a single apple can cost $24. The king of Japanese fruits is the muskmelon, which will see you shell out $125. The price sounds a little less crazy when you learn about the labor-intensive process needed to grow one, including selecting only the best seeds, pollinating the flowers by hand with a paintbrush, and massaging the fruit so its skin glows.

And there's a level up even from that. Watermelons grown in special shapes can run $1,500. And in 2016, a pair of Yubari King melons went for $27,000 at auction. So stop complaining about eating your five a day.

Nameless streets with misnumbered houses

Most countries have a very simple way of locating an address. Sure, your GPS might lead you into a lake every now and then, but basically, it's easy. There is a street name and a street number. Those numbers are in order, even if evens are on one side and odds on the other. It's not that hard to figure out.

Japan apparently decided that simplicity is no fun, which makes finding an address there a comically difficult process. According to Japan Info, most roads in the country don't even have names. Because many streets in Japan are so old, there is no grid system layout; instead there can be small, twisty lanes without signs, that intersect and veer off in bizarre ways. It can feel like being in a maze.

The address will also be the opposite to what most people are used to. Instead of going from specific to broader (number to street to town, etc.), it goes broad to specific. But once you finally find the right street, you should be fine if you know the number you are looking for, right? Wrong. Japan also decided that buildings should be honored by age, not location. The first or oldest building on a street often gets the lowest number, and the second oldest gets the next number, and so on. That means if you are looking for number 17, it might be found right between number 2 and number 38, completely illogically.

A language with three intertwined writing systems

If the Japanese writing system looks intimidating, there's a good reason. Modern Japanese uses three distinct writing systems for different purposes, each with its own history and each of which must be learned separately for a full reading knowledge of Japanese.

The most foundational Japanese writing system is hiragana, used for most of the most basic native Japanese words and grammatical structures and based on a simplified version of the kanji script. Hiragana symbols represent sounds, with one character standing for a simple vowel or consonant-vowel syllable. Katakana uses a similar symbols-for-syllables approach, but for foreign words. This doubling has the effect that many syllables can be represented by two distinct symbols. The third system, kanji, is a system of characters drawn from Chinese writing. These symbols encode not sounds but concepts (like Chinese writing), so you just have to learn them as whole symbols, along with their sounds. Over 2,000 kanji characters are commonly used in Japanese, making this the most intimidating aspect of the language for many students.

A fourth system some people use is romaji, the transcription of Japanese into the Latin ("Roman") alphabet. This can be useful for beginners to the language or if you're in a situation where you need something very basic to get by, but it's not really considered a true Japanese script.

A potentially fatal fish delicacy

Japanese cuisine features one dish that intrigues gourmands and goths alike. Fugu, made from the flesh of puffer fish, is part of the broader Japanese tradition of exquisitely cut and curated pieces of raw fish, but unlike its sister sashimis, it occasionally claims the life of an adventurous diner.

Puffer fish defend themselves in two ways: by puffing themselves up so their spikes stick out, and by being full of poison. The poison, tetrodotoxin, is more poisonous by weight than even cyanide and is produced not by the fish themselves but by bacteria that live inside them, manuacturing the toxin effectively as rent. In very, very small doses, tetrodotoxin produces numbness around the mouth. In not-that-much-bigger doses, it can cause general paralysis, which can arrest breathing, as well as potential disruptions to the heart rhythm. (Also, as with most poisons, gastrointestinal upset.) The toxin is not destroyed by the heat of the cooking process, which is less relevant for the fugu usually served as sashimi than for the other species that occasionally poison seafood lovers.

Puffer fish jawbones found at archaeological sites indicate that the people of Japan have been eating fugu for millennia. Occasionally banned for its lethality, in Japan it may now only be served by government-certified chefs. The persistent rumor that the best chefs leave a tiny bit of the poison for a telltale tingle is not true, but has contributed to Western fascination with the dish.

Remnants of nuclear war

While a number of countries have detonated nuclear weapons (on their own soil or someone else's), only Japan has suffered intentional nuclear strikes on population centers. In August 1945, during the last, desperate days of World War II, American planes dropped and detonated nuclear weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war but unleashing a new weapon that would frighten, and threaten, effectively everyone on Earth.

Today, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki are again thriving major cities, but their history as the only two urban areas to suffer direct atomic attack remains. In Hiroshima, the ruins of a building damaged but left standing in the blast have been preserved as a memorial. The Genbaku Dome was built in 1915 by a Czech architect to host an exhibition; located just over 100 yards from Ground Zero, the dome was stripped of its exterior by the explosion, leaving a distinctive skeletal framework. This site is regularly maintained to preserve it as it appeared shortly after the bomb detonated, and was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996.

While Nagasaki does not have a preserved structure like the dome in Hiroshima, the city does host a memorial and museum. Interested visitors can view the hypocenter, the spot on the ground directly below the bomb's atmospheric detonation, as well as memorials donated by various nations throughout the world.

Imperial treasures hidden from the public

When a new emperor takes the throne of Japan, among the honors and duties he (only occasionally, and not recently, she) receives is the care of three ancient treasures closely associated with the imperial throne. A sword (called Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi), a mirror (Yata-no-Kagami), and a jewel (Yasakani-no-Magatama) were, per legend, granted by Amaterasu, the Japanese goddess of the sun, to her grandson when she sent him to Earth to rule Japan. As these were gifts from both a goddess and a grandmother, they were highly prized.

The jewel and sword are presented to the new monarch on his accession; the mirror stays in its usual home, a shrine in central Japan, presumably to avoid the risk of breakage. The treasures are not, however, taken out of their cloth-wrapped boxes. Ever. By anyone. Not even the emperor. The last millennium-plus worth of imperial family members, courtiers, scholars, and people who happened to be in the room with the containers have reportedly only taken a combined single peek. The white smoke that allegedly spewed from the open box containing the jewel convinced Emperor Looky-Loo to quickly close it right back up. Japan's WWII-era emperor decided to surrender in part because of his fear that the treasures might fall into American hands during an invasion.

While scholars of Japanese history are able to make inferences about the treasures based on how similar items were made in Japan's remote past, details about them remain unknown. Strictly speaking, they may not exist (or may no longer exist), but this minor quibble need not dampen the air of ancient mystery and fascination that surrounds the three imperial boxes.

An emperor and an empress

Though much of the world has moved on from royalty, you can still find kings and queens here and there, and if you know where to look, even princes, emirs, and grand dukes. But there's only one place in the world you can still find emperors and empresses, and that's in the Japanese royal household. Only the current emperor Naruhito, his wife Masako, and his retired parents Akihito and Michiko still hold these glitzy titles.

The Japanese royal family is ancient, claiming to have reigned from 600 B.C. and with scholarly backing for their succession as far back as A.D. 500. The family's origin story was that the first emperor was the grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and this was the official line until after World War II, when emperor Hirohito renounced his claims of divinity in the face of clear evidence that he did not enjoy particularly robust divine assistance. Today, the imperial office is a ceremonial but culturally important position.

The current Japanese royal family is small and has only three eligible male members as potential successors to Naruhito. Women who marry are no longer royal, as the world learned when the telegenic Princess Mako married a commoner and became "merely" Mako Komuro. Japanese society and court-watchers have debated changes to the succession to expand the pool of potential heirs, but at the moment, no change appears imminent.

An artificial island just for foreigners

For much of its history, Japan preferred to remain mostly closed to the outside world. (Given the state the outside world is frequently in, they may have had a point.) But in common with nearly everyone else in the world, most Japanese people like interesting things from abroad. When Portuguese traders arrived in Nagasaki in the 16th century, they brought new cloths, tempting delicacies, and exotic animals like peacocks and a presumably bemused elephant. (The mess is not to be imagined.) Unfortunately for tradition-minded Japanese authorities, they also brought Christianity.

The solution for keeping interesting things coming in and troublesome ideas staying out was to build for the Portuguese an artificial island in Nagasaki harbor, onto which traders and their gods might be quarantined. After the Portuguese were booted out of Japan for being a bad influence, Dejima Island was conferred on Dutch interests instead. Trade continued to be funneled through Netherlandish interests on Dejima until Japan signed broader commercial treaties with the United States, United Kingdom, and Netherlands in the mid-19th century.

In 1904, improvements to Nagasaki harbor connected Dejima to the mainland. An ongoing restoration project aims to preserve and interpret the history of the site, including, in the long run, reopening the waterways to recreate Dejima's original shape as a fan-shaped island.

Thriving street fashion

Tokyo is not the only world capital with a thriving streetwear scene, but it's what most people think of when they think of street fashion. Vivid colors, bold choices, and offbeat sub-genres have all made the Japanese capital one of the most interesting places in the world to watch other people have clothes on.

While different trends have crossed the streets of Tokyo and risen to the interest of observers over the years, one of the most defining figures in Japanese street fashion is the Harajuku girl. Emerging in the mid-1990s in the namesake district of Tokyo, Harajuku style reacted against the previously reigning monochromatic minimalism of Japanese fashion. Kitschy, playful, and rooted in its specific place, Harajuku fashion was celebrated by designers and journalists who liked what they saw, and this fascination trickled outward to the outside world. Japan was not only a source of reliable electronics: It was cool.

But if Harajuku was the first contemporary wave of Japanese fashion to affect the outside world, it's hardly been the last. With Japanese designers showing at Paris shows even as a Tokyo Fashion Week has emerged as a tastemaker, Japan and its funky dressers have become key to the modern closet.

Pachinko

If you like being assaulted by loud noises and bright lights while watching steel balls scoot around the interior of a machine, but hate the agency the flippers on a pinball game gives you, Japan has just the ticket. Pachinko is a mostly passive game in which players purchase an amount of balls at loud, colorful machines. All the customer controls is the speed at which they release the balls, which then ricochet around the interior of the game machine. Some land in bonus areas, earning the player more balls.

When you're pleased with your score or are done spending money, you can cash out and exchange your theoretical balls for prizes at a counter present in every pachinko parlor. To allow for the fun of gambling without running afoul of Japan's anti-gambling laws, certain prizes can then be resold for actual money at windows just outside the pachinko parlor, allowing everyone to stay just on the right side of the law and giving players a minimal-but-real chance of hitting it big.

A dog that looks like a raccoon

Non-Japanese children who played "Super Mario Brothers 3" were sometimes confused by what happened when Mario picked up a special leaf on his adventures: He's in a raccoon suit now? The animal Mario sort-of became was not a raccoon but a tanuki, a dog that sort of looks like a raccoon and is a very real animal with an important presence in Japanese folklore. (They can't fly, though.)

Tanuki are omnivorous canids with raccoon-style, mask-like markings on their faces (though they lack the distinctive ringed tail of actual racoons). They like terrain where they can conceal themselves, choosing forests or dense growth, often alongside bodies of water, as they like to eat fish. Native to Japan and its mainland neighbors, an ill-advised Soviet attempt to farm them for fur means that escapees founded a wild population ranging through much of central and western Europe. Ironically enough, in Germany they inevitably encounter actual raccoons, also descended from escapees from fur farms.

According to Japanese traditional stories, two species of animal are naturally born with supernatural powers: the tanuki and the fox. Tanukis were believed to have the power to change their shape, theoretically into anything but often into a human being in order to prank or drink with them. This reputation has led to a mascotlike role for the tanuki in modern Japanese hospitality, with representations of the animal as it appears in the stories placed outside bars or restaurants. Come on in; you might get to party with a shapeshifting dog!

Yokai

Japanese folklore heavily features yokai, a class of supernatural entity with no real cognate in Western folklore. There's no clear one-word translation for yokai, which can encompass monsters, demons, ghosts, and other strange, otherworldly, or uncanny beings. Not even all Japanese people agree about the definite boundaries of the class, with some restricting yokai to only evil or only Japanese beings, while others will argue for broader scopes.

Yokai were first catalogued during the cultural boom of the Edo period, when Japan enjoyed the benefits of a central government able to clamp down on unrest. Edo-era Japanese consumers loved yokai, be they pulled from the traditional stories of various corners of Japan or new creations. Though pushed aside during Japan's push for modernization after 1868, yokai became popular again after World War II and are ubiquitous in modern Japanese popular culture.

Yokai are almost unbelievably diverse and range from the truly frightening to the very silly. Gashadokuro are gigantic, vengeful skeletons comprising the restless dead of unburied soldiers; shirime, on the other hand, have large eyes on their butts that they use to startle the unwary... and that's it. There are even some helpful yokai like the shy and many-eyed hyakume, who hang out near isolated temples and use their apparently detachable eyes to monitor passersby in case they should attempt to rob the sanctuary. When thieves do appear, the hyakume is more likely to scare them away than hurt them (but maybe don't push it).

Fried chicken Christmas dinners

Since Japan is not a traditionally Christian country, it's reasonable to expect that they might interpret Christmas loosely. And hey — we're not the Christmas police. But outsiders are nonetheless intrigued when they hear that one of Japan's most cherished Christmas traditions is a big ole bucket of fried chicken, generally courtesy of the KFC colonel himself.

As Japan recovered from WWII and then became wealthy, foreign franchises began to operate in the country, Kentucky Fried Chicken among them. The KFC footprint in the land of the rising sun and growing disposable income expanded rapidly, and while varying sources give different origin stories for exactly why the vaguely Southern fried-chicken chain became a yuletide hit, it unquestionably did.

In fairness, American-style fried chicken is not enormously exotic to Japanese diners, who have their own traditions of battered and glistening meat to draw on. Regardless of the exact circumstances, it was savvy marketing that tied the bucket-of-chicken experience to Christmas — and keeps the connection going, with statues of the colonel dressed as Santa when the season rolls around. Most importantly, it's become a tradition some Japanese families cherish, so place the eight-piece bucket by the frankincense and myrrh, spin the dreidel, and let a thousand traditions bloom.

Competitive child weeping

The Nakizumo Crying Baby Festival celebrates just that: the healthy, earsplitting wail of an upset infant. This Japanese festival, based on the belief that babies who cry well grow well (and that the sound can drive away evil spirits), is celebrated every spring by the parents of babies from 6 months to 2 years old.

The festival takes place all around Japan, with the biggest event in the old-fashioned Asakusa district of Tokyo. Parents wishing to have their babies participate in the famous festival at Asakusa must win a spot in an annual lottery (or, presumably, attempt to make their babies cry themselves). The babies are theoretically in competition with one another: The first cryer wins, with ties broken by the force and volume of the crying. Stoic babies are gently goaded by sumo wrestlers who chant "cry, cry!" at them; if this doesn't induce tears, organizers send out performers dressed as bird demons.