Grim Details About The Chernobyl Cover-Up

The nuclear power plant meltdown at Chernobyl, Ukraine in 1986 is widely regarded as one of the worst man-made catastrophes in history. On the surface, it might not seem so. Violent mass deaths like those caused by the very man-made atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed 320,000 people altogether. Chernobyl, by contrast, caused the initial deaths of two scientists, 29 first responders afterwards, and led to an estimated 6,000 people getting thyroid cancer, per the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. But, it's more the specter of Chernobyl that makes it stand out in memory, and the disaster's reminder of human fallibility and the inability to control our own creations.

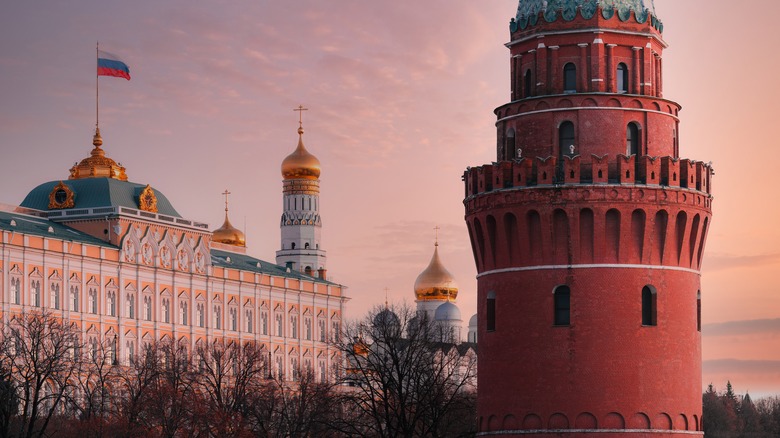

At the time, such implications were immediately apparent to the global community. The Soviet government, however, was slow to respond and very, very secretive, as Keele University explains. World leaders like Ronald Reagan criticized the Soviet regime, saying that the Soviet response to Chernobyl "manifests a disregard for the legitimate concerns of people everywhere," per The Washington Post. Soviet secrecy stemmed from a lot of factors, not the least of which was the desire to save face — both in the eyes of the wider world and its own public. No matter how its power had waned since the 1950s and '60s Cold War peak, the USSR was still very much in existence come 1986.

Ultimately, it's taken decades for details to come to light. Soviet silence was one misstep of many following Chernobyl's meltdown, made worse by bungled policies and communication between all those involved in the aftermath.

A concealed faulty reactor design

By all accounts, the Soviet coverup of Chernobyl started years before its 1986 disaster. The first two of Chernobyl's four reactors came online in the late 1970s, and reactors three and four came online in 1983. Numerous, subsequent investigations revealed that reactor four had an irregular, faulty design that wasn't adopted by other geographical regions across the world, as the World Nuclear Association describes. Soviet officials didn't merely disregard the dangers with the reactor, however, they actively suppressed them.

In 2021, Ukraine released documents indicating that the KGB and Soviet government were aware of problems at Chernobyl as far back as 1982, as Reuters reports. In order to "prevent panic and provocative rumor" the KGB kept radiation problems under wraps, as well as multiple, subsequent incidents in 1984. In 1983, when reactors three and four came online, the Kremlin was told directly that Chernobyl was one of "the most dangerous nuclear power plants in the USSR due to lack of safety equipment."

Around this time, Soviet engineer Valery Legasov also tried to tell colleagues at the USSR Academy of Sciences about the design problems with Chernobyl's reactor four, but was disregarded. Fear ruled the USSR, and no one wanted to speak up about a potential disaster. Even after the reactor blew, local officials dilly-dallied because they were afraid to take responsibility.

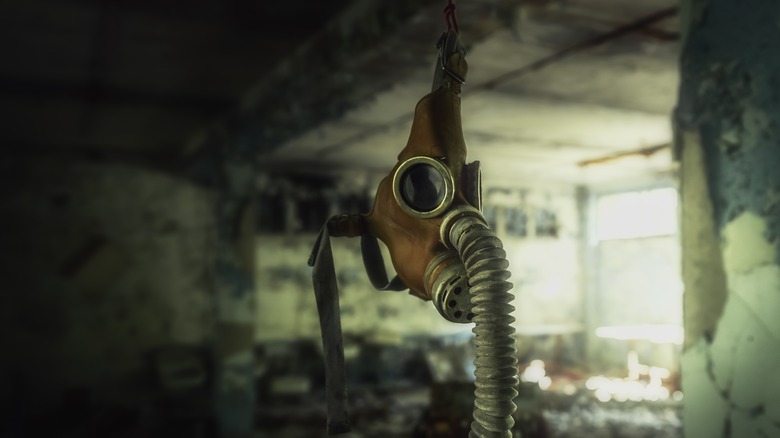

Ill-equipped first responders

The firefighters who arrived at Chernobyl following the explosion of reactor four were the first victims of the USSR's coverup and the first victims of Chernobyl's radiation. In an ideal world — or even a marginally sensible one — contingencies and regulations would be in place for something as devastating as a nuclear meltdown. But because of active Soviet suppression of information, plus indirect nondisclosure, the Chernobyl's first responders raced to the scene of the 1986 explosion utterly unprepared.

As Coffee or Die details, 186 total firefighters headed to Chernobyl to try and put out reactor four's blaze. The original teams got there shockingly fast — less than five minutes after the explosion, at 1:28 a.m. They had no gas masks, no radiation suits, no special equipment — nothing. There were no containment plans in place, no precautions, and no safety procedures appropriate for a nuclear meltdown. Simply put, the firefighters had the same equipment they would have had for a housefire.

The first firefighters actually climbed onto the roof of reactor four and stood right in the path of its rising, toxic smoke so they could hurl water down and onto the 3,600-degree Fahrenheit reactor below. The heat was so intense that Chernobyl employee Yuri Andreyev recalled seeing other firefighters sink ankle-deep into asphalt, as The Washington Post reported in 2006. Within three months 29 firefighters were dead from radiation exposure and related illnesses.

Residents kept in the dark

Even as firefighters fought the blaze at Chernobyl, residents in the nearby town of Pripyat realized something was up. On History.com, multiple witnesses describe police and military personnel roaming around town wearing masks and telling everyone to stay indoors, and aircraft showing up in the sky. This continued for a full 18 hours before evacuation orders came down the pipe. Then, at 1:00 a.m. on April 27, residents were given two hours to pack and leave and were told to go outside and wait in the road 50 minutes ahead of the busses leaving. And even as people were being shipped out of town on buses, no one was told anything about what was happening for a full 36 hours.

This lack of transparency — ironic in an age of Gorbachev's apparent "glasnost" (political transparency) — marked the continuation of the Soviet Union's coverup of the events at Chernobyl. We mentioned that local officials in the region of Pripyat refused to take action following reactor four's explosion for fear of reprisal from above.

After Pripyat's 30,000 citizens were evacuated, the Soviet government said nothing to the rest of its citizens or to the world at large. Forbes reports that May Day celebrations in the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv carried on as usual, with residents of the capital outside and at risk of radiation exposure. As The Washington Post says, Soviet officials only fessed up to what had happened after radiation was detected in Sweden. That was a week after Chernobyl's explosion.

Governmental concealment and finger-pointing

The international community was abuzz with talk of Chernobyl by the time Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev appeared on Soviet television on May 14, 1986 — almost three weeks after the explosion. He talked about the "malicious lies" of the world's nations, per Keele University, and how they have embarked on a "highly immoral campaign" by describing the enormity of the disaster at Chernobyl. Soviet citizens with contacts in other countries, meanwhile, heard a very different version of the tale. It was clear at this point that all of Gorbachev's talk of glasnost — political transparency — had amounted to nothing but secrecy.

Gorbachev, though, hadn't even received news of what had happened at Chernobyl until three-and-a-half hours after it happened, at about 5 a.m. Then, he decided to not call the government to an emergency session because it was the weekend and he didn't want to pester anybody. Gorbachev later said that "there was no understanding that the reactor had exploded and that there had been a huge nuclear emission into the atmosphere," per History.com. Whether this is true or not is anyone's guess.

According to The Washington Post, Chernobyl employee Yuri Andreyev describes the situation thusly: "In the USSR we do not tell a patient if he has cancer. Many times we treat people like they are children to be protected." Gorbachev did at least admit some measure of responsibility in that same May 14 television speech when he said that "the worst is behind us," as Atomic Archive recounts.

Contributing to the USSR's downfall

Despite all the denial, avoidance, concealment, and finger-pointing, the full truth of what happened at Chernobyl eventually came to light. It took until 1990 for the Soviet government to admit to its citizens that its safety measures, cleanup efforts, and general handling of Chernobyl had proved absolutely disastrous, per the Soviet paper Izvestia on the Soviet History archive at Michigan State University. Even by that time, four years after Chernobyl's reactor four exploded, housing for refugees from Chernobyl's fallout was just "getting underway slowly." Izvestia took a direct and critical approach to this whole debacle, ironically thanks to Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of perestroika — reconstruction — which allowed journalists to be more vocal in their criticisms of the government.

Even more pointedly, Chernobyl ruined trust between Soviet citizens and the government and helped undermine the Soviet veneer of power. The governmental admission of failure described on Izvestia only happened in the wake of waves of protest in Ukraine and Belarus, the areas most affected by fallout. In turn, as Forbes quotes historian Serhii Plokhy from his 2014 book, "The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union," Chernobyl's protests kickstarted greater national protests against the entire Soviet regime. One year after the aforementioned article was released, and five years after Chernobyl's meltdown, the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Ultimately, Soviet concealment of what happened at Chernobyl only contributed to the USSR's downfall.

[Featured image by Ivan Simochkin via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED]