The CIA's Top Secret Mission To Steal A Russian Nuclear Sub

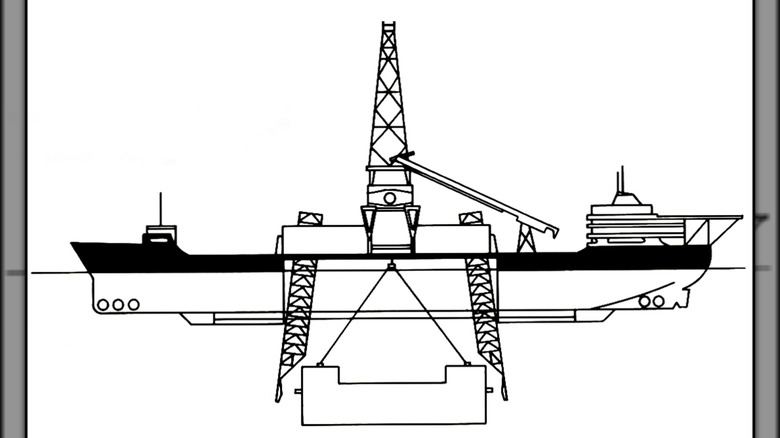

One of the great things about history is that it's filled with stories that are way more unbelievable and way more audacious than any bit of fiction ever written. One of those stories is the 1960s and 70s-era plot to recover a Soviet sub from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, and just that summary alone is enough to give some hints at what a wild plan it was (joining the ranks of others that definitely happened, such as the plan to use psychics to spy on the Soviets.) Things kicked off with the disappearance of a Soviet nuclear sub, of the same type as pictured above, in 1968, and the U.S.'s realization that if they could find it, they might find themselves with some invaluable information in hand that included tech that could be reverse-engineered, code books, and other valuable documents.

The hilarious thing is that the powers-that-be — which included the CIA and the Pentagon — knew exactly how risky, how unlikely, and how audacious the plan was. At the same time, it was kind of the perfect storm that came together to make it just too tempting of an opportunity to pass up.

The result was Project Azorian, a bizarre saga that cost somewhere around $800 million. (Adjusted for inflation, that's a little over $7 billion in 2023.) It ended up being one of the largest covert operations ever undertaken, required some feats of engineering that literally needed to be discovered and then developed, and when it was put in motion, there was one chance to get it right. Did they, and what went into it?

The disappearance — and discovery — of K-129

The beginning of what would become Project Azorian started in March of 1968, with the disappearance of a Soviet sub called K-129. At the time, the Soviets believed it had something to do with an encounter with an American sub, while the Americans suspected that it had experienced some kind of catastrophic equipment malfunction while on patrol in the general area of Hawaii. After the Soviet search dragged out into what was considered an embarrassing length, it was abandoned.

It's incredibly hard to find submarines that sink, but nonetheless, that was the time when the U.S. started getting super excited about the prospect of recovering the sub and its Soviet technology. Norman Polmar, historian and author of "Project Azorian: The CIA and the Raising of the K-129," told NPR that the U.S. had a secret weapon in the form of acoustic listening devices that were monitoring huge patches of the Pacific. The Navy and the Air Force teamed up to share their data, and it turned out that they had enough information to pinpoint where the sub actually was.

The CIA, meanwhile, had gotten some intelligence that suggested the Soviets were quite happy to abandon the search for the sub. Why? The information they had suggested the submarine was so far underwater that even if the U.S. did find it — which they were pretty sure they couldn't — they weren't going to be able to reach it anyway. And that's about when the Americans went, "Yes, but ... hold our beers."

There was a debate over the best way to lift the sub 3 miles to the surface

By the end of 1968, the U.S. government was sitting down to talk about how they could realistically launch a massive operation to recover a submarine three miles beneath the surface. Declassified CIA documents have revealed three main schools of thought as to the best way to recover the sub, the location of which had been verified during a recon mission carried out by the U.S. nuclear sub Halibut.

Government contractors pitched one plan to essentially develop a system in which a "buoyant material" would be forcibly sunk down to the level of the sub with the use of a ballast, which would then be dropped and — in theory — the sub would rise. Another plan also relied on buoyancy, but in that case, they proposed creating a system that would generate buoyant gases at the sea floor.

Neither of those things sounded easy, and neither does the third plan: Dubbed the "Total 'Brute Force' (Direct) Lift," the plan was to create a series of pipes, ropes, and winches that would be lowered to the sea floor — and again, that's a whopping three miles — to grab and lift the 2,000-ton (ish) submarine to the surface. And yes, that's absolutely what they went with. On September 11, 1970, the system got the official stamp of approval, and at the time, project heads estimated they had somewhere around a 10% chance of success.

[Featured image by Victorddt via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

How do you keep such a massive operation secret?

The initial part of the plan might sound like the plot of a Netflix film that definitely stars Jack Black in some capacity, but could it get weirder? Absolutely! The CIA needed a cover story to explain the appearance of what was going to be a massive ship carrying out some sort of major operations in the Pacific, and it was decided that the whole thing was going to masquerade as a deep-ocean mining operation. Fortunately for them, they had someone who was perfect to provide a cover for the whole thing: The eccentric and brilliant billionaire, Howard Hughes.

At the time, Hughes had already become a Las Vegas-based recluse, and was buying everything from local television stations to multiple casinos, hotels, an airline, and — most importantly to the story — mining claims.

Josh Dean is the author of "The Taking of K-129," and he explained to NPR how the whole thing started to come together. Hughes not only had the money to credibly fund such a massive endeavor, but he also had history in the mining industry. Even better? "He had [a] proven track record of doing bananas things that didn't make any sense." And at the time, deep-ocean mining was about as bananas as it could get. Dean added (to Vice), "It was almost like he was perfectly created for this character." And so, with Hughes providing the cover story, construction began on that ship called the Hughes Glomar Explorer.

We can neither confirm nor deny

Avoiding questions by using the phrase, "We can neither confirm nor deny," has been around for a long time, and even slipped into popular lexicon. When the CIA officially joined Twitter in 2014, their first tweet was surprisingly tongue-in-cheek, as they posted, "We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet." (Perhaps ... but we're all still wondering what the CIA has to say about aliens)

The phrase was first used in connection with Project Azorian, and it was actually: "We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested but, hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified, and could not be disclosed." It was developed as a way of answering Freedom of Information Act requests that would protect the classified information in question, which, initially at least, was the existence of the massive not-only-a-mining-ship Hughes Glomar Explorer. When the media started sniffing around the project, they realized they couldn't confirm the existence of the vessel, and couldn't deny it, either — hence, the phrase.

Josh Dean, author of "The Taking of K-129," told NPR that the CIA was also challenged in court by somewhat of an unlikely candidate: Rolling Stone. They issued the carefully crafted response, "And now we all deal with that phrase on a daily basis."

The construction of the Hughes Glomar Explorer was a ridiculous undertaking

Designing the ship and the equipment was just the start, and it was made even more difficult by the fact that the Hughes Glomar Explorer (HGE) needed to not only be outfitted to rescue the submarine, but it needed to give all of the appearance of being a cutting-edge vessel pioneering some seriously experimental technology. And so, the Deep Ocean Mining Project was established to — reportedly — start developing a way to recover precious metals (including manganese and cobalt) from the ocean floor at depths up to 17,000 feet.

Construction of the ship started in 1971, and it wasn't expected to be fully operational until 1974. Costs skyrocketed by about 66%, and had reached the point where there was an internal campaign to end the program altogether. More and more people officially voiced their opposition, as questions started being raised about just what the project hoped to discover from the sub.

Still, the project went ahead as planned. The ship — complete with a central, on-board dry dock — left the Pennsylvania shipyard on April 12, 1972, for a series of completely ordinary tests and trials with a completely ordinary crew ... aside from the handful of people sent in undercover to keep an eye on things. It passed shallow-water tests, proceeded on to deep-sea testing, then headed to Bermuda for preparation on what would be a shockingly long journey.

[Featured image by TedQuackenbush via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

The long way around

Because the ship was too big to get through the Panama Canal, they were going to have to take the long way around the tip of South America, stopping to change crews along the way. Techs and engineers made use of the time to finish kitting out the equipment, but declassified CIA documents have confirmed that most of the people who served in the crew had no idea what the ship's purpose truly was.

The ship passed through the Strait of Magellan on September 6, 1973, and in a bizarre twist, things very nearly went completely sideways. On September 7, representatives from the company that had overseen the building of the Hughes Glomar Explorer, Global Marine, arrived in Santiago with supplies, and were scheduled to meet up with the ship on the 12th. Then, on September 11 — and this is the sort of thing that absolutely cannot be made up — a major revolution kicked off in Chile.

The city of Santiago was shut down, and declassified CIA documents are sadly lacking details. What little they do describe is a series of events "which reads like a Hollywood script ... [and involved] much intrigue and suspense" in getting the necessary equipment on board the ship during the first days of what would be an incredibly violent coup, which would overthrow the socialist government in favor of a dictatorship. Hilariously, the entire plan to oust Chilean president Salvador Allende was also sponsored by the CIA, which is perhaps a perfect example of the importance of communication.

Storms and a medical emergency helped maintain the ship's cover, even as the Soviets circled

The Hughes Glomar Explorer set up on arrival at the recovery site on July 4, 1974, and was almost immediately delayed by bad weather. That wasn't the biggest problem, though, and on the 12th, they were faced with a major decision: Should they answer a call for medical assistance from a nearby British merchant ship?

They did, and it wasn't an entirely selfless decision to make. When the HGE chatted with the ship in need — the Bel Hudson — they confirmed that they were definitely on a mission to test deep-ocean mining capabilities. They were careful to broadcast over open channels in the hopes that any Soviet ears would hear, and it wasn't the only time they were questioned: A Thai tanker also inquired about what they were doing, which was deemed "social in nature."

Of course, the Soviets were there, too. A naval ship called the Chazhma showed up on July 18, and brought with it a helicopter that did a few fly-bys of the HGE. They were so interested that some on the HGE became convinced they knew exactly where the sub was and what was going on. Plans were made for the possibility of being boarded, and although the Soviet ship got within 500 yards and communications were exchanged, they moved on later that same day. Then, on July 22, a Soviet salvage tug appeared ... and after taking more photos, they moved on.

[Featured image by Tequask via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Recovery didn't go as planned

Here's where things get a little ... less clear. Historian Norman Polmar did a deep dive into declassified CIA documents for his book, "Project Azorian: The CIA and the Raising of the K-129," but the key word there is "declassified." Not all the files have been released, and there are still many that have been redacted, so Polmar stresses (via the Smithsonian) that, "the conventional wisdom has become that this was a failed mission. [The CIA has] allowed that belief to be what everyone understands, but why would they not? I always say, 'We have no idea what they got.'"

The official story told by the CIA is that in the process of lifting the sub, it broke in half. Most of the 300-foot-long sub ended up sinking again, and another section was successfully recovered by the Hughes Glomar Explorer. When an approximately 40-foot section was hauled to the surface, it contained the remains of six Soviets — who were buried at sea with full military honors. It also was said to have contained a few manuals, and two nuclear-tipped torpedoes.

Officially ... nothing super cool. Polmar, at least, suggests that there might still be more to the story, but whether or not it ever gets released is another matter entirely. There is one footnote to that, though, and that's the fact that the CIA considers the mission a success with respect to the cover mission: deep-ocean mining. The HGE actually did, in fact, recover manganese samples from the ocean floor.

Here's the weird story of how the existence of the project went public

It didn't take long for news of the top secret operation to break wide open, and the story became yet another one of the U.S. government's accidentally spilled secrets. Just the fact that Project Azorian remained such a well-kept secret during the construction of the Hughes Glomar Explorer, as well as the globe-trotting expedition itself, is pretty amazing, and it's only fitting that the mission went from top secret to public knowledge in a bizarrely fitting way: a story in the Los Angeles Times. At least, sort of.

Before the HGE set sail, a series of documents were stolen from one of Howard Hughes' offices. Among the documents was a key piece of the paper trail that connected all the dots between Hughes, the CIA, and the actual, top-secret plans for the supposed deep-ocean mining ship. Even as law enforcement scrambled to get the documents back, the media noticed that government law enforcement agencies seemed to be paying a suspicious amount of attention to what would otherwise be a civilian matter.

What happened next happened quickly: The story made it to the national news, the Soviets realized what was going on, and any future plans were scrapped. The Soviets, meanwhile, assigned some of their own military to the site, putting a definite end to future shenanigans. (Interesting in more strange government plans? Check out the Pentagon's zombie apocalypse preparedness plan.)

What happened to the ship?

After investing all that time, energy, and money into the Hughes Glomar Explorer, it didn't just sit around ... did it? It actually did — for almost 20 years, before a Texas-based company called Electronic Power was hired to overhaul the electrics. When they headed to California to see what they had to work with, they were shocked to find that it was pretty much a pristine time capsule. CEO John Janik has said (via the American Oil & Gas Historical Society), "Everything was just as the CIA had left it, down to the bowls on the counter and the knives hanging in the kitchen. Even though all the systems were intact, this was by no means an ordinary ship."

The HGE was outfitted into what it was supposed to be in the first place: a drilling ship. After 17 years of service to Global Marine Drilling — during which it was recognized by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers as a technological wonder — it ended up being passed into Swiss hands, renamed, and anyone who thinks this is going to have a happy ending for the ship would be sorely mistaken.

By 2015, the HGE — now called the GSF Explorer — was one of around 40 ships in the drilling fleet. Then, it became one of many casualties amid falling oil prices: It was sold for scrap in a deal with an unnamed buyer, which put a rather ignominious end to what was one of the U.S. government's many strange stories.