The Untold Truth Of Judas

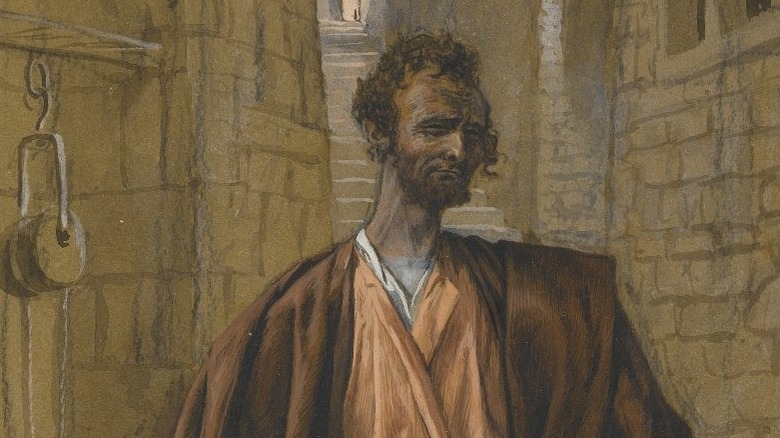

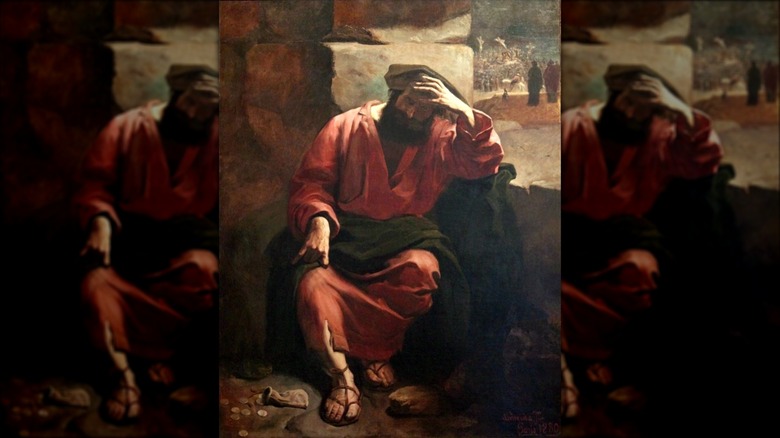

For some, the concept of stone-cold betrayal can be summed up in just one name: Judas. Yet while his name may today be considered a byword for treachery and the man himself is often called one of the most famous traitors in history, the real story of Judas Iscariot is far more complicated than something that can be summed up in a single word.

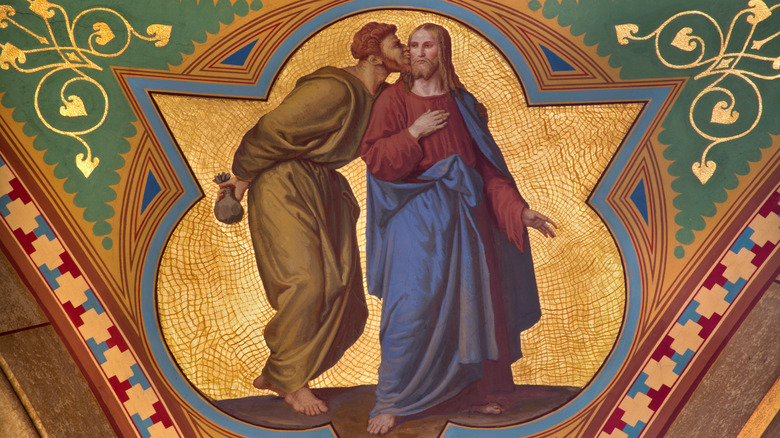

First appearing in the Gospels of the New Testament as a member of the original 12 disciples of Jesus, Judas is a rather mysterious figure who is presented with practically no background and very little information on his motivations. Given his major role in the story of Jesus and the crucifixion — in the Bible, Judas is the one who turned Jesus over for trial and execution at the hands of the Roman authorities, giving Jesus a rather historic kiss in order to identify him — that lack of information has proved troublesome for many who have encountered the story. It doesn't help that, over the generations, misconceptions and folklore have arisen that further complicate the figure of Judas.

So, what's the real story? Digging deep into the reality of what's said about Judas in the Gospels and beyond, even religious scholars may be surprised by what we know — and don't know — about Judas Iscariot. This is the untold truth of the man who is widely considered one of the Bible's biggest villains.

We don't know much for certain about Judas Iscariot

As much as Judas has become an infamous villain, there is precious little information about him in the Bible — or anywhere else. He first appears in the Gospel of Mark, which was written around A.D. 70, some 40 years after the death of Jesus. Before that, there is no mention of Judas or even a story that clearly outlines the betrayal of Jesus. Instead, the first we get is a brief mention of him in Mark 3:19. There, the writer, naming the 12 disciples, finishes the list by calling out "Judas Iscariot, which also betrayed him."

Even after he steps onto the scene, there isn't much to learn about Judas. There are a few mentions of group activities done by the apostles, of which Judas was almost certainly included. Then, there's the story of his betrayal of Jesus, which the gospels of Matthew and John claim was done for money, while Luke points toward the influence of Satan as the true motivator. For his misdeeds, he dies, and then promptly drops out of the Biblical narrative.

Further complicating things is the fact that Judas was a fairly common name in 1st-century Jewish communities, with some people going by Yehudah or Judah instead of the more Greek-influenced Judas. For the incautious reader, it can be easy to get all of the various Judases and Judahs mixed up with the far more notorious Judas Iscariot.

Iscariot may have been an eyebrow-raising name

The Iscariot part of Judas' name has remained a subject of debate for many years, not least because none of the Gospel writers bothered to explain the name. It could be that Judas was simply from the Judean city of Kerioth, which lent him the name and would have set him apart from the rest of the disciples. The rest of the group was largely from outside of Judea; many disciples came from the northern region known as Galilee.

Others posit that some scribe somewhere made a mistake and wrote Iscariot when they really ought to have written Sicariot. This would have potentially linked Judas to the Sicarii, a Jewish nationalist group that agitated for violent reprisals against Romans. However, this a tricky theory to champion, as the Gospels don't overtly link Judas and the Sicarii. What's more, the nationalist group appears to have been most active well after Judas would have died.

Yet another theory links the Iscariot name to Judas' cause of death, turning the title into a retcon that may not have applied to the actual man during his lifetime. Here, Iscariot may be derived from iskarioutha, a blended Greek-Aramaic term that could have meant choking or constriction, perhaps fatally, as Joan E. Taylor argued in a 2010 issue of the Journal of Biblical Literature. Ultimately, however, many scholars have concluded that we simply can't uncover the real meaning of the Iscariot name.

Some theorize Judas was an extremist Zealot

To many, the betrayal committed by Judas in the Gospels is baffling. With practically no background information on the man, it's hard to understand why a seemingly devoted follower of Jesus — surely, you don't become one of the 12 disciples without displaying some real dedication — would turn around and give it all up for a monetary reward. To that end, speculation about Judas' political affiliations has sprung up, lending more motivation to this mysterious man and his actions. Some academics have even suggested that he was a member of the independence-minded Zealot movement, though this theory has proven to be controversial.

If Judas was a Zealot, he certainly would have been more embroiled in the political realm than we may have suspected. The Zealots were a political group that operated in 1st-century Jewish communities and which agitated for Jewish independence and violent reprisal against Roman colonizers. Zealots were even known to fight back against Jewish people who cooperated with the polytheistic Romans. They occasionally revolted against the Romans and some of the most intense members of the group, the dagger-wielding Sicarii (which some have linked to the Iscariot part of Judas' name), were said to have taken out political assassinations.

Judas was the disciples' treasurer

Both John 12:6 and John 13:29 mention that Judas was in charge of the disciples' money, but the earlier verse goes even further than simply stating that Judas carried the bag full of common funds. Instead, John 12:6 claims that Judas took the opportunity to skim off the top, taking some of the money for himself when it was meant to support the group or provide help to the poor. Later in the story, as in Matthew 26:14-15, Judas is seen bargaining with the priestly leaders in the Jewish community to betray Jesus for 30 pieces of silver. This points to a possible interest in more money and a motivation for his treachery.

Whether or not financial interests were really behind Judas' betrayal in the Gospels, it is clear that money was a vital part of Jesus' ministry. Though it's all but certain that Jesus and the disciples were operating on a tight budget (not to mention that Jesus was generally very skeptical of accruing too much wealth and not handing it out to the poor), they still needed some money to survive. That might have come from begging, along with funding provided by more financially stable supporters, such as Joanna, the wife of a royal steward. Yet, however the money may have arrived in the disciples' common purse, it would hardly have been considered okay for Judas to sneak a bit for himself instead of sharing as he was supposed to.

Judas' betrayal was a surprise to the other disciples

When it comes to Judas, both Jesus and the reader of the Gospels have foreknowledge of all his misdeeds — the very first mention of Judas in Mark 3:19 plainly states that Judas is going to betray Jesus. Yet, Judas' fellow disciples were caught unawares.

Take John's version of the Last Supper. In John 13:21-30, Jesus tells the assembled group of his followers, "Verily, verily, I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me." The disciples proceed to look around at each other and then, flummoxed, ask Jesus who it is. Even after Jesus baldly demonstrates that it's Judas, they remain confused. When Jesus tells turns to Judas and says, "That thou doest, do quickly," they believe he is telling Judas to take the group's money bag and hustle out to buy supplies or help out the poor. Other Gospel retellings of the Last Supper likewise point to Judas as the villain, though less overtly and always with shock from the gathered disciples.

It's not as if the disciples were necessarily bad judges of character. For instance, in Mark 6:7, Jesus calls up the 12 disciples — which would have included Judas — and "began to send them forth by two and two; and gave them power over unclean spirits." From the perspective of the disciples, there's little reason to believe that Judas would be given such weighty spiritual responsibilities if he wasn't a stand-up guy.

His motivations are surprisingly murky

While the Biblical narrative hammers home the perception that Judas Iscariot is a betrayer, it doesn't do much to explain why he turned Jesus over to the authorities. The Gospels present a variety of explanations or, in the case of Mark, no explanation at all. Matthew presents the argument that Judas did it all for a monetary reward, while Luke and John advocate for the role of Satan in Judas' actions. John 6:70-71 even goes so far as to call Judas a devil himself.

So, maybe it comes as no surprise that, in all the confusion, religious scholars have made hay of the many different explanations for Judas' betrayal. It could have been a desire for money — Judas was apparently in charge of the group's funds and, according to some accounts, was basically embezzling from Jesus and the disciples.

Or, if you subscribe to the idea that Judas was a rebel with possible links to the anti-Roman Zealots, it could be that he was frustrated by Jesus seeming to play along with the Romans (or at least not signing off on violence against the colonizers). Some have taken the opposite tack, wondering if Judas was instead fearful of an uprising that could have formed around Jesus and caused serious trouble for the Jewish people. Ultimately, however, there's just too little information to go on, meaning Judas' motivations will likely remain forever unknown.

Some argue Judas was especially close to Jesus

The image of Judas as villain is so ingrained that the 2006 publication of the Gnostic Gospel of Judas was supremely controversial, largely for how it dramatically reframes Judas. Though it was mentioned by other Christians as early as the 2nd century, the text itself — or at least a Coptic copy of an earlier version — wasn't uncovered until the 1970s. From there, it followed a weaving path of ownership that saw it stored improperly, leading to a loss of about 10% of its text.

The Gospel of Judas was already notorious in the 2nd century, when church leaders were decrying it as heretical. That hasn't changed much in the 21st century, not least because the Gospel paints Judas as the only one who truly understood the message and mission of Jesus. As the apocryphal text has it, Judas is given the weighty task of sacrificing Jesus, bearing the curse of his act, and then ruling as the spiritual leader of a lower realm. In the work, Jesus even laughingly refers to this fate, asking, "Why are you all worked up, you thirteenth demon?"

There are hints of this closeness in the canonical Gospels, too. In John 13, Jesus reveals that Judas will betray him, but then appears to give Judas a special task and sends him out to complete the course of his disloyalty (though it's worth noting that John says Satan enters Judas at this point in the story).

Judas played an important role in the crucifixion

The crucifixion of Jesus, his resurrection, and the subsequent redemption of humanity so central to the timeline of Holy Week and Christianity in general couldn't have happened without Judas. After all, in John 13:27, Jesus tells Judas to get a move on with the betraying, implying that Judas had to fulfill his role for the process to move forward. That doesn't stop John or the other writers of the Gospels from painting Judas as a supreme villain who may or may not be under Satan's power, but it at least begins to acknowledge the central place that he plays in the story.

Other texts outside of the Bible take this concept even further. The 2nd-century Gospel of Judas is an esoteric Gnostic text that flips the character of Judas from his villainous spot. Here, Judas is not only a key figure in the story of the crucifixion but is also a beloved disciple of Jesus, tasked with the vital job of turning Jesus over. In this version of events (which is apocryphal and therefore not officially accepted by many Christian churches), the task is a regretful but necessary one. Still, though Judas is depicted as the only disciple who's really keyed into things and worthy of the task, it's not a desirable job. In the Gospel of Judas, he is denied entry into what is essentially heaven and will have to perpetually exist on a lower level away from Jesus.

The Bible is unclear about his cause of death

When it comes to Judas' end, the books of the New Testament are hardly in line. In Matthew, a supremely guilty Judas throws away his money and then dies by suicide. Yet none of the other Gospels says a thing about how Judas met his end, despite pinning him as a serious villain.

In Acts 1:15-20 (believed to be written by the author of the Gospel of Luke), the apostle Peter says that Judas used the money to buy a field, "and falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out." Some have concluded that the falling down part could be describing an accident. Others say this particularly disturbing part of the Bible is an oblique way of referring to Judas' death by suicide.

Non-canonical works also claim to tell the story of Judas' death, sometimes with seriously gory details. Early Christian writer Papias of Hierapolis wrote that Judas eventually became so grotesquely swollen that he was unable to see or even properly walk, to the point where he died by suicide. The 4th-century Gospel of Nicodemus has Judas discussing the possible resurrection with his previously-unmentioned wife, who's in the middle of preparing a chicken for dinner. She attempts to reassure her husband, saying that Jesus is as likely to rise from the dead as the bird in front of her; when the chicken does just that, Judas goes to die.

His story has been linked to antisemitism

As with many other stories and figures from the Bible, Judas has taken on something of a second life as a folkloric character. Legends that grew in the intervening centuries crafted details such as Judas' red hair, which was assumed in medieval and Renaissance thought to be representative of lies and betrayal. Yet this detail points to a far more unfortunate association of Judas. Historically, antisemitic thought linked red hair, Judas, untrustworthiness, and the Jewish people. Though hair color is hardly representative of morality, the association remained. Meanwhile, other traditions, like the Easter burning of Judas in effigy in Europe and beyond, arose. Links between Judas and antisemitic thought may have also been darkly useful for an emerging religion, one that sought to distinguish itself from its Jewish roots.

Some scholars have even suggested that the Judas story is largely a fabrication that has been used to prop up antisemitic narratives through the centuries, though this idea remains controversial. Many other prominent New Testament scholars, like Bart Ehrman, argue that Judas was still a real person.

The supposed links between a betraying Judas and Judaism have generated real pain and violence for innocent people well into the modern era. Scholar Louis Painchaud has even gone so far as to link the Judas story and the horrors of the Holocaust, writing that perhaps the modern urge to reexamine his story is linked to lingering guilt over the evils of that time (via The New Yorker).

Muslim traditions tell a different tale of Judas

Judas doesn't just show up in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. He also occasionally pops up in Muslim religious texts. However, he doesn't exactly make it to the main show, as the Quran doesn't mention Judas Iscariot directly. In fact, the religious text doesn't say anything about a betrayal of Jesus, though the Quran does refer to Jesus as a prophet and notes that he had disciples.

Dig a little further into Muslim scholarly works, however, and Judas does sometimes appear. There, he's often referred to as Yahuza al-Iskhiriyuti. While he is very much associated with Jesus and even linked to the crucifixion in these works, his role is dramatically different from that of the Biblical Judas. Some even claim that Jesus — commonly known as 'Isa in Arabic — ascended to Heaven without being crucified. But this means that someone else was potentially apprehended, tortured, and executed in his place. To Quranic commentators, this may well have been Judas, whose face and even voice may have been divinely transformed to more effectively fool the crowd. It's hardly a consensus view amongst believers and scholars, but it is nonetheless an interesting take that may bring a new dimension to the religious and cultural history of Judas Iscariot.