The Worst Part Of The Apollo 1 Disaster Isn't What You Think

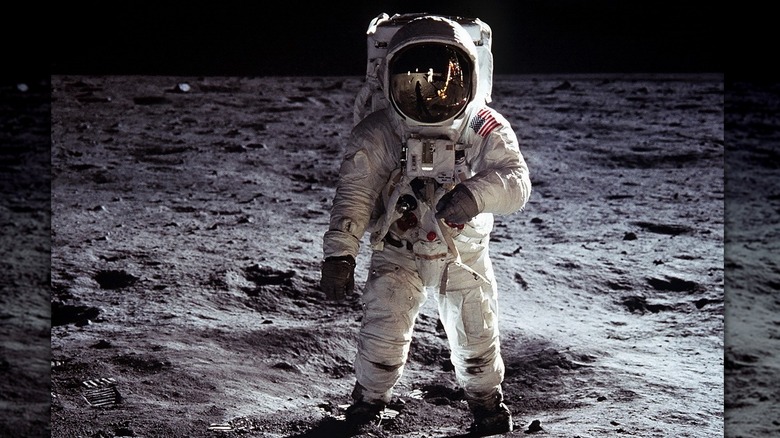

In the current day and age, space travel is one of those things that seems like it might soon be within reach for the everyday person. Well, relatively speaking, at least — space tourism is still very much in the realm of the rich, as attested by the many photos and news stories of celebrities and billionaires being launched into space.

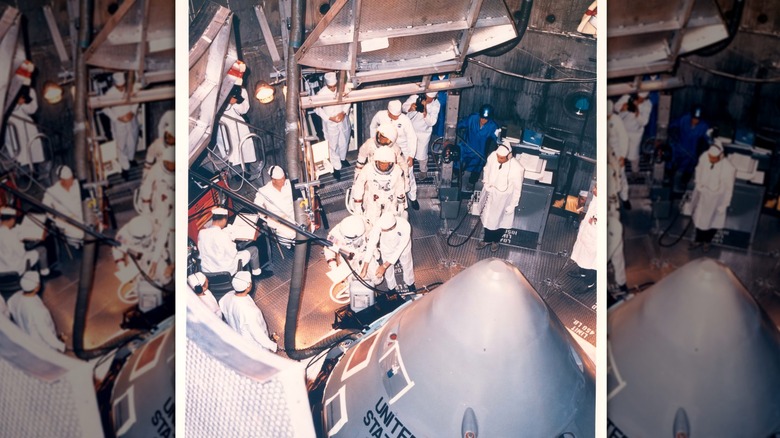

Despite all the glamour, though, it's worth remembering that space travel is a dangerous thing, and has a history frequently punctuated by tragedy. In the U.S., there were the Challenger and Columbia disasters, but also the first major incident: the Apollo 1 disaster. In short, Apollo 1 (then designated Apollo 204) was supposed to be the first crewed flight of the program. But the craft never got off the ground; during a series of tests on Cape Kennedy's launch pad on January 27, 1967, a fire broke out in the command module. All three astronauts inside — Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee — died in the flames.

The entire incident was tragic — there's no denying that — but the more you look into the incident, the more you realize that, like the space shuttle Columbia, the worst part of the disaster isn't what you think. Perhaps the actual worst part of Apollo 1 wasn't just the deaths, but rather the preceding decisions and other circumstances at the time surrounding the incident.

The tests were far from smooth

Disasters like those involving the Challenger and Columbia shuttles took place during their respective missions, but Apollo 1 differs in that her crew never actually made it to their launch. Instead, the accident took place in the middle of a testing day, and even before the catastrophic fire, it was already something of a mess.

To put it simply, the day played host to a ton of different technical issues. Most notable were the communications issues; the astronauts inside Apollo 1's command module should have been able to talk with their coworkers in the nearby buildings, but for whatever reason, those systems weren't working. The whole thing really got onto Gus Grissom's nerves in particular, and he yelled out, "How are we gonna get to the Moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings?" (via Astronomy).

But there were other strange goings-on. For one, Grissom pointed out a weird smell in the air — sort of like spoiled milk — only for no one present to be able to figure out what it was. The command module itself was giving the astronauts a number of problems. Pumping it full of oxygen kept triggering alarms for no apparent reason, on top of making it incredibly difficult to even open the hatch. But seeing as the boosters didn't have any fuel in them, the crew figured that things were safe enough to continue forward.

The causes of death weren't what you'd expect

The astronauts and technicians present at the Apollo 1 test knew that something had gone wrong when they saw a bright flash of lights on their screens — the fire that quickly engulfed the entirety of the command module. So the natural conclusion to draw is that Gus Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee were killed by that fire. But that's not exactly what happened. The fire wasn't what killed them — at least, not directly.

Of course, the fire did cause extensive burns to all three men, but autopsies determined that the majority of those injuries were suffered post-mortem. In other words, the fire itself wasn't the cause of death. Rather, the fire actually burned through the oxygen hoses on the astronauts' suits, and they fell unconscious pretty quickly. They weren't able to get out of the module, and all the while, the fire filled the cramped space with toxic gasses like carbon monoxide, with the carbon monoxide specifically causing heart attacks, which was the true cause of death.

The astronauts' lives weren't the only ones put at risk

Of course, there's no ignoring the fact that the Apollo 1 disaster led to the deaths of Gus Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee, but it's also worth mentioning that the other technicians present at the scene lived through a harrowing experience of their own.

Though the crew running the test was spread out through multiple rooms, the command module was directly connected to an area called a white room. The technicians stationed in that room reacted immediately to the fire, trying to free their friends, only to be blasted by columns of fire themselves as pressure vessels ruptured and sent flames arcing toward them, singeing the papers on their desks. Those who arrived in the room later found it filled with fire and smoke, ashes, and burning pieces of Teflon. The men continued trying to pry the hatch open, despite choking on fumes and finding themselves blinded by smoke — all while knowing that a nearby escape rocket would explode if the fire got to it.

That's not to say that the technicians stationed in the control room, physically separated from the fire, had it easy. Instead (via Vice), they could only hear the cries from the astronauts as the fire began, which ended with Chaffee pleading, "Get us out of here! We're burning up!" Then an anguished scream — the last thing they would hear, and all while knowing they were helpless to do anything.

The pure oxygen environment

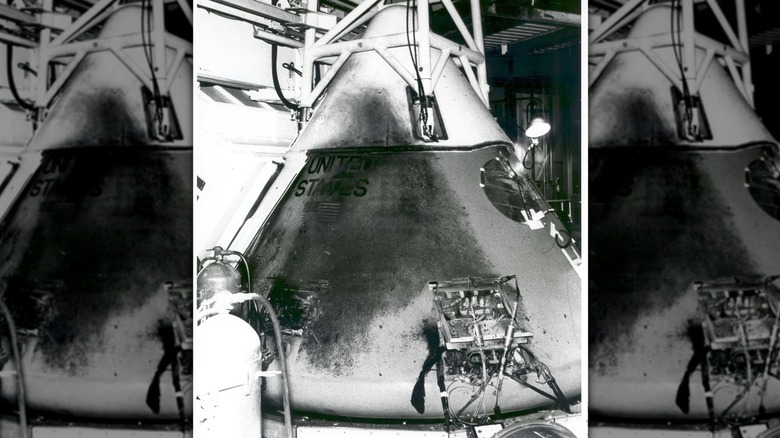

When it comes to the cause behind the fire that spontaneously erupted in Apollo 1 and killed the three astronauts, there's one particular aspect that was mentioned a lot at the time of the incident: the environment inside the command module. The space was pressurized with pure oxygen at 16.7 psi, and oxygen is especially flammable, so any spark would've been enough to create a huge flame.

But there's a whole history here that actually makes this a lot more complicated. Back in 1959, during the testing of the earlier Mercury capsules, engineers intended the capsule's environment to be a mix of nitrogen and oxygen, but logistically, it would've been too heavy and the mix ratio too complicated. Hence, they settled on pure oxygen at 5 psi. The problem? That worked in space, but for ground tests, the low oxygen content caused an astronaut to pass out, and so they upped the pressure to 15 psi.

That higher pressure was effectively grandfathered into the Apollo tests, but the main difference was that the Apollo modules were a lot larger than the Mercury capsules. More space meant more oxygen, and that, in turn, meant more possibility of fire. Engineers recommended that mix of nitrogen and oxygen again, but NASA nixed that idea for fear that an accident might cause decompression sickness in that environment. So, they kept with the pure oxygen atmosphere instead.

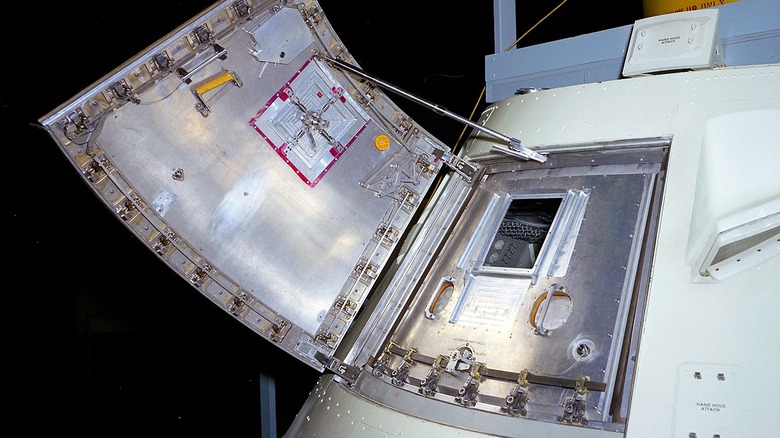

The hatch sealed their fate

Considering the rapid and intense nature of the fatal fire, the hatch to the Apollo 1 command module might seem like a pretty irrelevant thing to consider. But as it turned out, that hatch was no simple thing, and some poor design decisions might have condemned the astronauts to death. After all, if the three men had been able to quickly escape, then the tragedy would have been avoided.

The hatch was, in fact, a death trap. It consisted of multiple different parts — including an inner and outer hatch, both of which served different purposes and had to be opened using different tools. The inner hatch also opened inward, which was a problem on its own. The pressure inside the module was higher than it was outside — a good thing in space, since it helped keep the hatch closed, but a bad thing on land, because it made the door even harder to open. Engineers recommended including explosive bolts that could knock the hatch off its hinges in an emergency (exactly the kind of emergency that Apollo 1 ultimately faced), only for NASA to shoot that down.

Missions after Apollo 4 corrected both of those mistakes by introducing an easily removable unified hatch, but for the crew of Apollo 1, they had to struggle with a hatch that was destined to lead to failure. They trained at opening the hatch in 90 seconds — still a fairly long time — and even that proved impossible for the strongest of the three. Not a good sign, surely.

The command module became a tinderbox

The pure oxygen atmosphere in the Apollo 1 command module was already a disaster waiting to happen. But oxygen wasn't the only very flammable issue.

There's plenty of technology we wouldn't have without the Space Race, but at the time, American astronauts had discovered the usefulness of a very different technology: Velcro. It was a supremely practical solution to a uniquely space-based problem; things that could start floating around in zero gravity were easily secured by just sticking them to Velcro positioned all around the interior of the spacecraft. They'd gotten pretty dependent on it, and it was tradition to customize Velcro positions prior to missions — to the point that fire prevention rules were getting forgotten. After all, Velcro is flammable, and it was getting stuck to places less than a foot from potential ignition sources.

On its own, that was already courting danger, but Apollo 1 was even worse. Accounts of the command module described it as "wall-to-wall Velcro" (via Smithsonian Magazine), and in addition, immediately prior to the test, technicians threw some nylon nets inside as well. They were meant just to catch anything that fell, but no one realized until afterward that the increased oxygen content would cause it to burn twice as fast as in earlier tests. All in all, Michael Collins later calling the module "a tinderbox" was quite accurate.

Political pressures led to negligence and blindness

On examination, many of the failures that led to the Apollo 1 tragedy were technical in nature. However, some of the factors were pure human error.

On one hand, this wasn't a bunch of amateurs who were constantly making mistakes. Astronaut Michael Collins responded to the official NASA report on the disaster by explaining that even the smartest of people could miss the most obvious things, stating: "I don't know why, we're blind to them. I mean, it makes us think that the quality of our engineering across the board was juvenile, yet it wasn't! It was very good engineering" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

But that blindness might have also been a bit more intentional. Earlier in the decade, President John F. Kennedy had promised that people would watch the moon landing, and that started putting pressure on NASA. As a result, the teams working on Apollo 1 were taking risks and ignoring problems. Flight director Gene Kranz explained that there were plenty of botched simulations, plans were far from finalized, and procedures kept changing over and over, but nobody did anything to address it. All anyone wanted was to keep to their schedule, so they kept pretending there weren't issues. In taking the blame for the tragedy, Kranz summed things up by saying, "We were rolling the dice, hoping that things would come together by launch day, when in our hearts we knew it would take a miracle" (via AIP).

NASA higher-ups were fully aware of the dangers

In much the same way that the Challenger Space Shuttle explosion could've been avoided, the same could be said of Apollo 1. Had technicians just seen the dangers or kept safety protocols in mind, then maybe three men wouldn't have died on that day. But it goes far deeper than technical mistakes. NASA officials were explicitly told just how much danger they were courting — and they chose to ignore it.

The contractors who recommended that the Apollo missions be tested using a mix of nitrogen and oxygen were completely shot down by NASA officials. Over the course of multiple different arguments, they were told to just do their job without question, despite internal notes fully recognizing the validity of those concerns, one of which even mentions the possibility that "a number of otherwise nonflammable materials, even human skin, will burst into flame in a pure oxygen atmosphere" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

General Electric vice president Hilliard Page even made the prophetic statement: "I do not think it technically prudent to be unduly influenced by the ground and flight success history of Mercury and Gemini ... The first fire in a spacecraft may well be lethal." Officially, NASA's response was blasé, expressing faith that a fire was unlikely, but once again, internal documents betray that confidence. The program's director, Joe Shea, privately noted, "The problem is sticky ... We think we have enough margin to keep fire from starting — if one ever does, we do have problems."

No one had any faith in the spacecraft

In retrospect, there are a lot of reasons to think that Apollo 1 was a doomed mission from the start, whether that has to do with rather obviously unsafe testing parameters, or the other errors and mishaps that had already occurred earlier that day. But the most telling thing might be the fact that the tragedy could be foreseen not only from an outside perspective, or with hindsight, but rather, from those directly involved in the mission, who could see the problems coming from a mile away.

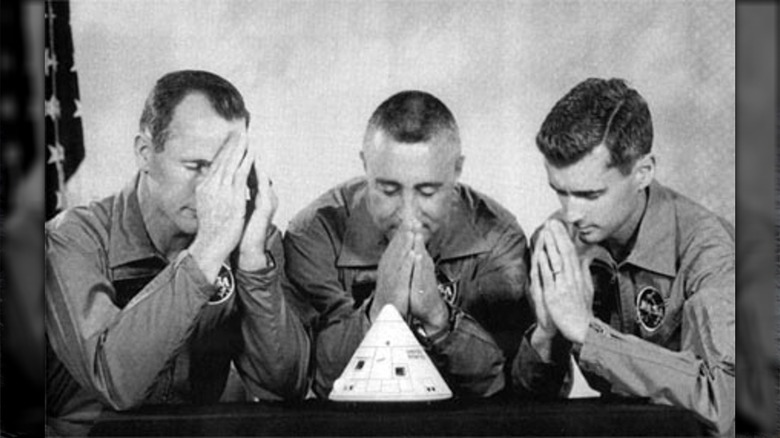

The three astronauts — Gus Grissom in particular, though — seemed to have some pretty major shortcomings about the fate of their mission. Grissom reportedly told a journalist that he'd consider the mission successful if he just got his men home alive — not exactly a high bar — and astronaut Wally Schirra even told him, "If you get the slightest glitch ... get outta there. I don't like it" (via Astronomy). To really make their feelings known, the three men of Apollo 1 even went so far as to take a mocking photo which has instead become tragically ironic: all of them with their heads bowed in prayer, just hoping that they would come home safely.

And they had good reason to be concerned. The craft was undergoing constant modifications to both its hardware and software, said hardware was literally broken or leaking at times, and those problems were well known among the crew. Far from an ideal situation.

This wasn't Gus Grissom's first brush with death

Apollo 1 has gone down in history as one of the most tragic events in the history of American space exploration. That said, it wasn't the only time that a NASA mission ended with danger and the possibility of death. Not only that, but it isn't even the first time Gus Grissom specifically has had to face the possibility of death.

The mission took place on July 21, 1961, and it was the second of NASA's Mercury-Redstone missions, in which astronauts were to make suborbital flights in preparation for fully putting them in orbit. Most all of those missions went off without a hitch, but not in Grissom's case. After his Liberty Bell 7 capsule splashed down in the ocean, it was supposed to be retrieved by a helicopter, but before that could happen, the hatch blew off spontaneously — likely due to some static discharge caused by the helicopter's rotor wash. Water flowed in, and Grissom tried to throw himself out of the sinking capsule. Unfortunately, he found water seeping into his oxygen inlet, dragging him down alongside his craft; it was a lucky thing that those in the helicopter saw him waving and lifted him from the water, just nearly saving him from drowning.

The Liberty Bell 7 was eventually recovered, and Grissom was ultimately safe and well, but the mission still remains the first to ever encounter a brush with death.