The Untold Truth Of AEW

For wrestling fans, the biggest story of the year is unquestionably the rise of All Elite Wrestling. A new promotion built around international fan-favorites, AEW has a deal to debut on mainstream cable television later this year and the financial backing of a legitimate billionaire, and with an announcement that they may be offering health care to wrestlers — something that WWE does not do for its roster of "independent contractors" — the excitement about how AEW could shake up the industry isn't just limited to what's going on in the ring.

As fresh and new as it might seem, though, something like AEW doesn't just show up out of nowhere, and their story goes back a whole lot further than a bunch of indie wrestlers selling out Chicago's Sears Centre in September 2018. From the legacy of one of pro wrestling's greatest minds to the surprising road to success that ran through a YouTube comedy series to a dismissive challenge from a journalist that set the whole thing off, here's the real story behind AEW.

The Legacy

It's impossible to talk about AEW without focusing on Cody Rhodes. Along with Nick Jackson and Matt Jackson, the tag team collectively known as the Young Bucks, he's the face of the company and the primary force behind it — and he also happens to be carrying on a family legacy of the man who is arguably the single most important creative force in wrestling history, especially if you're looking beyond WWE.

Cody is, of course, the son of "The American Dream" Dusty Rhodes. In front of the camera, Dusty was a three-time National Wrestling Alliance World Heavyweight Champion, the beloved "son of a plumber" who gave the world a strong contender for the greatest promo of all time. Behind the camera, however, Dusty spent years working creatively as a booker. He was instrumental in moving pro wrestling to the modern format built around massive "supercard" shows, and scripted some of the NWA's greatest stories — many of which wound up revolving around him. That might sound like a recipe for disaster, but Rhodes was both beloved by fans and also, as ESPN's Brian Campbell put it, "never afraid to endure an incredible scripted beating" in order to get his opponents over as the villains. That tendency would even lead to him being fired in 1988, when he staged an attack by the Road Warriors that saw him being "stabbed" in the eye, complete with all the blood that the TV network had specifically told him not to include.

The comparison between Cody and his father is inevitable, partly because Cody has drawn it himself in some pretty interesting ways. The fact remains, however, that since Dusty was active on the creative side of pro wrestling until his death in 2015, Cody literally spent his entire life around one of the masters of the art form, watching him work and clearly learning more than a few things.

The state of things

To really understand how AEW came about, you have to understand the current state of professional wrestling, which pretty much comes down to the idea that for most people, "wrestling" is World Wrestling Entertainment.

That's not to say it's the only wrestling going on. Independent wrestling is in the middle of a pretty incredible renaissance. Streaming services have made it easier than ever to keep up with stuff that would otherwise be local, and have allowed American audiences to follow international promotions like New Japan Pro Wrestling more easily than ever. That said, as far as wrestling that the average person can just sit down and watch on TV without going hunting for it, WWE is really the only game in town, and they've been that way for almost 20 years.

With the demise of WCW and ECW in the early 2000s — both of which were bought by WWE, adding to the incredible tape library that might end up being the company's greatest strength — WWE has been the only wrestling promotion with a mainstream television presence. There is, of course, Impact Wrestling (formerly TNA), but with some shaky creative decisions, business practices like not actually signing a top star to a contract, and multiple moves to increasingly obscure networks, they've never been within shouting distance of dethroning WWE. It turns out, however, that being a monopoly isn't all that it's cracked up to be.

The Post-War Monopoly

WWE tends to thrive on competition. The hottest period in pro wrestling history came when they were directly competing with WCW for viewers, and while that was ultimately unsustainable, it's a catalyst that they've tried to recreate over the years by splitting their own roster into brands. The thing is, while fans remember the company pushing the envelope in terms of action and content in order to beat their rivals, the effects of being the last company standing go well beyond what you see on the screen.

By its very nature as the largest wrestling promotion, WWE is in a weird place with regards to its business practices. They're the target of an incredible amount of scrutiny, leading to highly publicized stories about how their superstars don't get health benefits or the outrage among both fans and wrestlers about doing shows for the reigning monarchy of Saudi Arabia after the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. At the same time, they have no real reason to change, since they're basically the only globally recognized company in their field. Even if you don't like what they do, there's no real viable alternative if you want to watch mainstream pro wrestling.

The same lack of a viable alternative applies to the wrestlers themselves. Right now, WWE has an embarrassment of riches when it comes to talent, with a massive roster that's full of incredible performers. As much talent as they have, though, and as many hours of television as they're willing to put out every week, and as much as they're willing to pay wrestlers more than they could be making anywhere else, there's only so much screen time to go around. WWE has signed plenty of wrestlers that could (and should) be huge stars that there quite simply isn't room for, and even when the product itself is very good, as WWE's shows frequently are, that stagnation can take its toll. That's why, despite the fact that WWE is pretty firmly entrenched as the #1 wrestling company in the world, people on all sides of the industry are very interested in finding some kind of viable, profitable alternative.

Joining the Club

While their upcoming shows boast plenty of familiar faces to WWE fans, AEW has its real origins in something that many casual fans never saw, even if they can recognize the seemingly endless T-shirt designs that came out of it: New Japan Pro Wrestling's Bullet Club faction.

The Bullet Club was formed back in 2013, and in the early days, it was built primarily around Prince Devitt, known today in WWE as Finn Balor, along with Karl Anderson, Tama Tonga, and Bad Luck Fale. Before long, it would expand to include the Young Bucks and Luke Gallows, the crew that would bring it to its biggest prominence. At its height, the Club was like a "greatest hits" version of bad guy factions, with the comedic irreverence of D-Generation X, the monochromatic color scheme and "invasion" stylings of the NWO, and the championship dominance of the Four Horsemen that led them to collectively hold every title in NJPW. Plus, they cheated. A lot.

As members were signed to WWE contracts, other wrestlers cycled through, including Kenny Omega (a dude who has had multiple matches ranked at 7 out of 5 stars), Hangman Page, and Cody, a group that might seem pretty familiar if you've been keeping up on the matches announced for AEW's Double or Nothing.

Being the Elite

While everyone involved with AEW is a seasoned veteran of pro wrestling, it's worth noting that the company has as much to do with something Cody and the Young Bucks did outside the ring as what they've accomplished in it. In fact, it's easy to argue that AEW wouldn't be happening at all if it weren't for, of all things, a YouTube series.

In 2016, after splitting off from the Bullet Club and forming a faction called the Elite, Cody and the Bucks launched a YouTube series called Being The Elite. Originally designed as a sort of behind-the-scenes, road-diary style series following the group and their travels, BTE eventually became much more. Entire storylines were fleshed out through the series and major announcements like the formation of AEW and matches for their events were made there.

Being the Elite blurred the line between the stories being told through pro wrestling and the reality behind it, and built a tight continuity over which the Elite themselves had complete control, separate from any of the (many) promotions they were wrestling for. It allowed them to take advantage of the platform to reach an audience that was maybe not interested in following Ring of Honor or New Japan, but were definitely drawn by charismatic performers to see goofs like the Young Bucks having a living room feud with Santa Claus. As a result, they forged a connection with die-hard fans that made the entire group even more popular than they already were, and they did it completely outside of the existing structure for promoting pro wrestling.

The Meltzer challenge

The overwhelming popularity of the Young Bucks is pretty indisputable. Along with Elite stablemate Kenny Omega, they're one of the few acts in wrestling so popular that they're able to turn down multiple offers from WWE because they can make more money (and retain much more creative control) working outside the world's most dominant wrestling promotion than within it.

In 2017, that prompted a question posed to Dave Meltzer, longtime wrestling journalist and commentator, about whether Ring of Honor, a company that prominently featured Omega, the Bucks, and Cody, was popular enough to sell out a 10,000-seat arena. Meltzer's response was a short "Not any time soon." This, for those of you keeping track at home, is one of those instances of someone deciding to do something entirely because they were told they couldn't do it.

Sure enough, Cody announced that the Elite were going to promote a "supercard," putting up their own money to prove that they could, in fact, put 10,000 butts in 10,000 seats based entirely on their own merit. The result was appropriately called All In, a risky venture that many fans felt had the potential to change wrestling by showing that large-scale success was possible outside WWE. Tickets went on sale on May 13, 2018, and despite the show only having one match announced at the time, they sold out in half an hour. For his part, Meltzer said he was happy to have been proven wrong.

All In pays off

To put it mildly, All In was a big deal. With its 30-minute sell-out, it became the first non-WCW, non-WWE wrestling show in 25 years to sell over 10,000 tickets, and by the time those fans were crowded into Chicago's Sears Centre (or streaming the show at home), it had turned into an incredible international showcase. Not only did it feature ROH talent, but the Elite also brought in matches from Mexico's CMLL and AAA promotions, Impact Wrestling, New Japan, and the National Wrestling Alliance. It even had a match with TV's Green Arrow, Stephen Amell (who had previously wrestled Cody at WWE's SummerSlam in 2015), and he was actually pretty good.

While virtually all the matches were well received by fans and critics, it was the NWA World Championship match that might end up being the most important in the long run. In addition to winning the championship that had defined much of his father's career, Cody sported a pair of boots with "6:05" emblazoned on them.

That might've been a little confusing for younger fans, but for those of us who grew up watching World Championship Wrestling, the meaning was clear. WCW Saturday Night, the show that Dusty Rhodes always referred to as "the Mothership," aired for years at 6:05 PM on TBS. It was a notable tribute to Dusty, and also an interesting piece of foreshadowing.

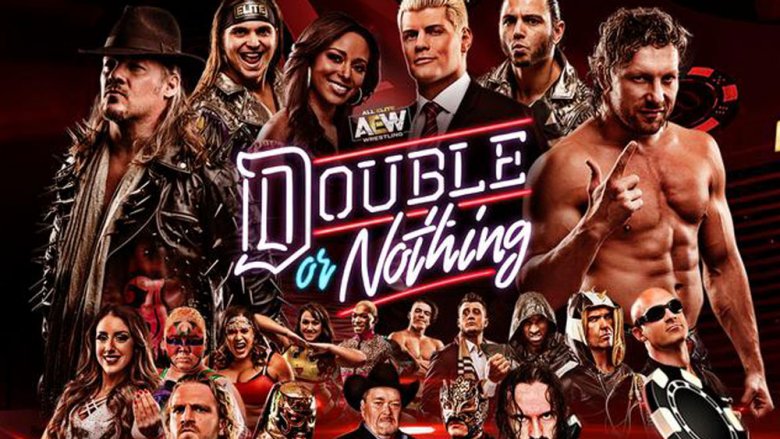

Going Double or Nothing

With the overwhelming success of All In, the question was no longer "can they do it." Instead, it had moved to "can they do it again," and "when will they inevitably try?" The answer came on January 1, 2019, and, of course, it was part of the YouTube show.

In the 132nd episode of Being the Elite, the Elite announced not just that they'd be doing a second show called Double or Nothing — both keeping the gambling theme and making it even more literal by setting it at the MGM Grand Arena in Las Vegas — but the formation of a new promotion, All Elite Wrestling. In the days that followed, it was revealed that Cody and the Young Bucks would be serving as executive vice presidents (and presumably as bookers) for AEW. It was also announced that they'd signed a roster that included up-and-coming stars as well as established legends like Chris Jericho and the somewhat less well known but still awesome Glacier, the Mortal Kombat-esque ice ninja from the final few years of WCW.

More importantly, however, was the fact that they had the financial backing of Shahid and Tony Khan, a father and son pair of billionaires who also own the Jacksonville Jaguars, with Tony serving as president. Maybe they were inspired by the impending return of the XFL to compete with Vince McMahon on two fronts at once?

AEW Nitro?

The formation of a new wrestling promotion, even one featuring popular stars like Cody, Omega, the Young Bucks, and Glacier (bear with us on that last one), isn't exactly huge news. The fact that they have financial backing that can afford top talent is a bigger deal, but if AEW really wanted to compete with, or even provide an alternative to WWE, they needed one specific thing: mainstream television. Streaming is great, but TV provides access to a more casual audience that goes beyond the 10,000 people willing to pony up for tickets to the live event, which is what a company truly needs to thrive.

And that's exactly what AEW got, in a place that's both surprising and completely appropriate. On May 15, TNT announced that they'd be airing a weekly AEW show. It's notable for a couple of reasons, including the fact that TNT is a major cable network that's available worldwide, but also because of that network's history with wrestling. TNT (a sister channel to TBS), was the home of WCW Monday Nitro in the late '90s until WCW folded in 2001, and was where that company had their greatest success and eventual failure.

The announcement included a couple of relatively subtle nods to the network's history with wrestling, including a fiery background for the AEW logo that mimicked Monday Nitro. There was a much deeper cut in the form of a tweet that read "we're back in the wrestling business." That's a reference to a phone call Ted Turner made to Vince McMahon after he bought WCW, telling him "I'm in the wrestling business!" McMahon famously replied "that's great, I'm in the entertainment business." But with an emphasis on "entertainment" that's led to things like running a full trailer for The Secret Life of Pets 2 during a match in a split-screen, fans might just be looking for a little more wrestling.

The future of pro wrestling?

Only time will tell what the future holds for AEW, but with name recognition, financial backing, a TV deal, and experienced stars at the helm, it certainly seems like they're poised for some kind of success. The question of what they're going to do differently than other companies, including WWE, remains, but we have an interesting example of how they might be using the internet going forward.

One of the matches set for Double or Nothing was Hangman Page vs. PAC, but for reasons that aren't quite clear, the match was pulled from the card. Rather than just not having the match, however, PAC faced Page seven days before Double or Nothing on another show, with the entire match put up for free on AEW's YouTube Channel. Whether this was a legitimate problem or just a story to generate buzz and get more eyes on the product (something that's always a possibility in the world of pro wrestling), the fact remains that it was dealt with in a way that a traditional promotion like WWE simply could not do, and it showed a willingness to deliver to the fans. That's a very different approach than what we've seen before in wrestling, and might just be the first step in AEW being something very different for the future of pro wrestling.