The Most Popular Jobs During WWII

The wheels of society might squeak during an extreme crisis like wartime, but they still keep turning. The discussion of World War II can often revolve solely around the military engagements and various atrocities of this dark era in human history. However, only a fraction of people actually served in any of the armies. While the sizes of the militaries were impressive — Germany had over 18 million military personnel between 1937 and 1945, the U.S. over 16 million, and the Soviet Union nearly 34.5 million — the combined total of them all amounted to less than 6% of the world's population at the time.

This means that while the armies, navies, and air forces did the actual fighting, a considerable part of every country's war effort happened on the homefront. There was much to be done both at home and in the military, and some jobs turned out to have extra prestige — in one way or another. Here's a look at some of the most important, esteemed, and popular professions during World War II.

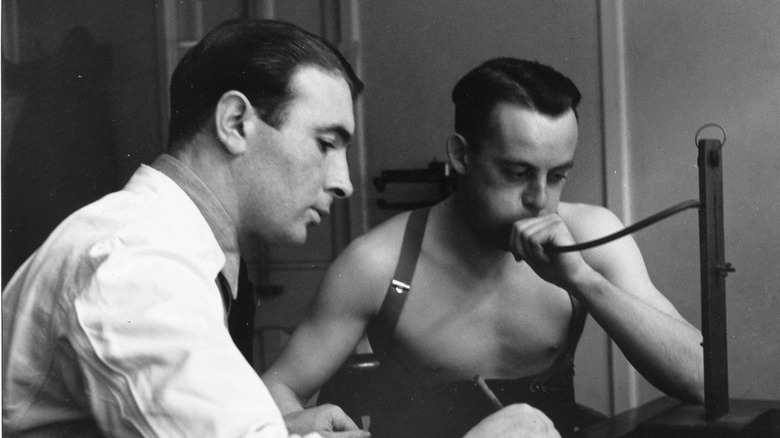

Medical professionals

Calculating the number of people who were wounded in World War II is hardly an exact science, but both Allied and Axis powers clearly dealt with a massive number of wounded individuals — over 670,000 for the U.S. alone, and over 5 million for Germany. It's probably reasonable to assume that a significant amount of these people considered medical professionals to be their absolute favorite wartime job, since their survival could hinge on their access to one ... provided it wasn't a cruel Nazi doctor of the Josef Mengele variety.

WWII-era military medical service was essentially developed from the systems that were already used in World War I, but its elements were supercharged based on previous experience and scientific advancements. Treating the wounded wasn't the only crucial job doctors and other medical professionals did during the war, either. For instance, in the U.S. their function was threefold. They were the people who determined the fitness of recruits, and they also attempted to keep the troops as healthy as possible even before they got wounded or became ill. A large number of general and specialized tasks fell under these basic functions, from dentistry to veterinarian tasks and evacuation of personnel who weren't fit for battle.

It was a lot of work, no doubt. Still, in the U.K., being a doctor was a comparatively cushy gig in the sense that it was a reserved profession. This means they couldn't be conscripted for military training as easily as most other professionals.

Artist

It may not be immediately obvious that art might play a significant — let alone popular — part in times of war, but it actually had a huge role in World War II. Consider Laura Knight's 1943 painting "Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring," an image of a female British factory worker that became a popular symbol during World War II. In the U.S., this dark era of human history birthed a stream of iconic propaganda posters, such as the famous "I Want You for the U.S. Army" one with the image of a pointing Uncle Sam. The Soviet Union had been big on propaganda since its inception in 1917, and was quick to turn its posters and cartoons against the Germans once the clash between the countries became imminent.

It wasn't just leaflets and posters, either. Moving pictures were also a big part of the wartime effort on both sides of the conflict. Germany's most prominent filmmaker was Leni Riefenstahl, who made several movies that exalted the Nazi ideals. Meanwhile, the U.S. had the entire might of the Walt Disney Studios producing a wide variety of propaganda works that reimagined classic characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck to serve the war effort.

Riveter

In the U.S., the manual labor job of a riveter became iconic in World War II for one very particular reason. Rosie the Riveter was both a symbol and a blanket term for all women who worked in usually male-dominated industrial jobs. A character bearing this name became a popular icon for both the U.S. homefront's war efforts and, later, women's rights and independence.

Interestingly, J. Howard Miller's famous "We Can Do It!" motivational poster that's now associated with the Rosie the Riveter character had nothing to do with her during wartime and only became part of the Rosie lore when it resurfaced in the 1980s. However, the image of Rosie was already prevalent during the WWII era, and had a significant cultural presence in works like the 1943 song "Rosie the Riveter," the 1944 movie of the same name, and a well-known illustration by artist Norman Rockwell.

As mentioned, riveting was just one of the many labor-intensive jobs Rosie symbolized, but thanks to the way the era's popular culture targeted this specific job as a symbol, it certainly seems to have packed an extra prestige punch. Just ask Rose Will Monroe, a very real WWII-era riveter who found herself starring in a war bond promotional film ... simply because Hollywood found out about her name and profession.

Factory worker

A job being popular doesn't necessarily mean that people enjoy it. It can also simply mean that a whole lot of folks are doing it. Symbolic figures like Rosie the Riveter aside, factory workers in general were in heavy demand during World War II, and as such, a great many people ended up filling those roles. By sheer numbers alone, the wartime effort of Great Britain is hard to beat. Near the end of the war, the country had recruited a third of its civilians for war-related factory work.

Such mass employment is impressive in its own right, but it also played a surprising role when it came to women's rights ... though only in the long term. Britain's war workers included 7 million women, and the U.S. also recruited a great many women to work in industrial jobs during wartime. Unfortunately, this didn't last. After the war was over, the men once again took over most of the jobs – but women had already proved they could do the work just as well, and eventually reemerged in the workforce.

Crystal grinder

Crystal grinding might sound like the kind of gig that can get a person arrested, but it actually had nothing to do with narcotics. The job involves shaping crystals for the quartz radios that were prevalent in the Allied war effort during World War II because they were reliable and couldn't be detected by the enemy. The grinder was in charge of machining the crystal so that it could pick up desired radio frequencies.

A good crystal grinder had plenty of job opportunities even after the war since the technology was used in all sorts of gadgets. With a bit of extra training, their skill set could also be applied to making lenses — an important component in many fields of tech.

The fact that crystal radio transmissions couldn't be pinpointed by the enemy was good news for the men on the front lines, especially since it was entirely possible to jerry-rig a DIY version if a person knew what they were doing. Such "foxhole radios" were important morale boosters for soldiers who weren't exactly drowning in entertainment options, so it's easy to imagine that someone who knew how to work a crystal was pretty popular in their unit.

Munitions worker

Among the many people who worked in factories during World War II, there were specialized workers whose job was considered extremely important ... and particularly dangerous. Munitions workers were responsible for producing the various tools of war, from guns to ammo and explosives. The work was truly meaningful, but could also be deadly. Apart from bombing risks and the potential for explosive accidents, the workers were exposed to various dangerous chemicals that could cause grievous injuries.

As in several other wartime industries, many munitions workers were women. One strange symptom of the work gave them the nickname "Canary Girls," which came from the way the TNT they handled could turn their skin temporarily yellow. As Gladys Sangster, whose mother worked in one of the factories, told the BBC, the unnerving effect wasn't merely cosmetic. "I was born [during the war] and my skin was yellow," she said. "That's why we were called Canary Babies. Nearly every baby was born yellow. It gradually faded away. My mum told me you took it for granted, it happened and that was it."

Despite the health dangers, munitions work was seen as a highly valuable endeavor that was done in all sorts of places — even ordinary basements. In fact, even the Palace of Westminster — London's iconic House of Parliament famous for Big Ben — had a munitions operation going, and high-ranking government officials were invited to work there.

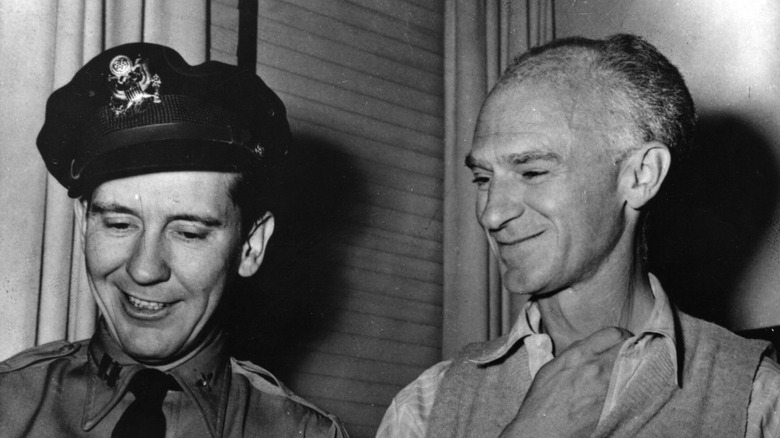

Journalist

For members of the military and civilian people alike, news of how the war was going was understandably important during World War II. As such, journalists willing to brave the theater of war played an important part, to the point that they could become famous for the work they did.

One of the most esteemed American WWII-era journalists was Ernie Pyle, a seasoned reporter who specialized in the everyman viewpoint and had a knack for getting to know his subject matter firsthand — such as reporting about the messed-up truth of the Dust Bowl after personally traveling the area. During WWII, Pyle threw himself into frontline reporting. He became a well-known heroic figure for his extensive and honest stories that recounted his views of events that ranged from the bombings of London to the everyday lives of soldiers.

Among the best-known female WWII correspondents was Martha Gellhorn, a pioneer who'd already covered the Great Depression and the Spanish Civil War. She covered several important events during the war, and would probably have been present for many more if her husband at the time — one Ernest Hemingway — hadn't tried his best to keep her away from the frontlines, even pilfering her correspondent credentials for himself near the end of their marriage. Gellhorn didn't let a lack of official permits prevent her from returning to war journalism. She simply bluffed her way to the beaches of Normandy during D-Day and continued her work.

Photographer

If a normal picture is worth a thousand words, the right wartime photograph might just be able to fill entire books. World War II has no shortage of iconic photos, like Joe Rosenthal's famous image of U.S. marines raising a flag during the battle of Iwo Jima. The higher-ups recognized the importance and impact of such images, and as a result, military photographers and even specialized photo corps like the British Army Film and Photographic Unit arose. Apart from documenting history, such photographers were also tasked with providing visual material for military use.

Photojournalists were also around. As with many other professions, wartime photography also gave newfound job opportunities to women, though only four ever worked as official war correspondents. One of them, Lee Miller, started as a model before becoming a photographer, and eventually transitioned from fashion images to taking pictures of women who contributed to the war effort on the homefront. She then traveled to Normandy after the Allied invasion. On one particular occasion, a communications mishap sent her to the absolute front lines during the battle of St. Malo ... though this got her in temporary trouble with the higher-ups, who weren't particularly amused to find her there. Regardless, Miller continued to cover the war as the Allies proceeded and was present when the full extent of the horrors that had taken place in German concentration camps was discovered.

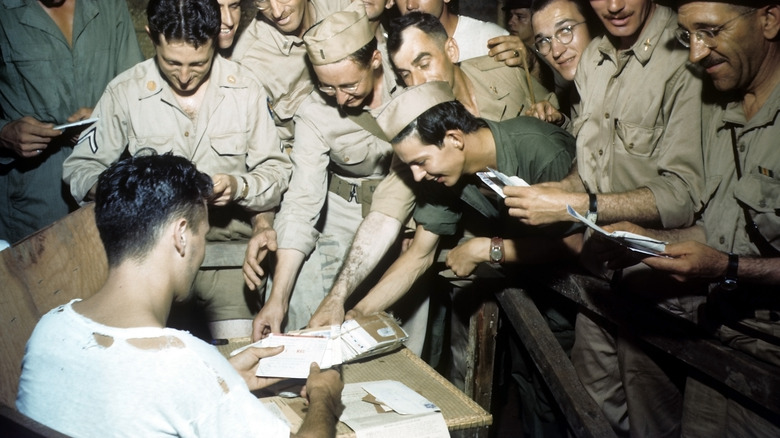

Postal worker

"Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds" isn't actually the U.S. Postal Service's motto, but a quote from the historian Herodotus. However, based on its World War II accolades, the USPS might as well have run with it, and added a line about artillery shells for extra flair.

Postal service, as it happens, was a crucial part of the war, as the soldiers fighting abroad had lots of correspondence with their loved ones. The USPS answered the call, delivering both good and bad news the best it could amid the battles and turmoil, and even collaborating with the Red Cross for whatever letters prisoners of war might be able to send and receive. They also introduced new services like the V-mail — V stood for "victory," of course — which allowed them to convert the letters to microfilm for delivery, thus saving valuable cargo space. The British Post Office was doing its best as well, both delivering mail and training to protect its office buildings from the enemy.

The importance of postal service for a warring country's morale wasn't lost on the U.S. Office of Strategic Services. In a 1945 project called Operation Cornflakes, it created 96,000 propaganda letters that were carefully crafted to resemble ordinary German mail and planted them in a destroyed mail train in bags that resembled authentic ones used by the German postal service.

Cook

Apart from mail, food was massively important to keep people's spirits up during wartime. As such, a cook who could provide decent meals for the troops was held in extremely high regard. "I think the cook traditionally in the Army has always had a sort of bad rap," historian Dr. Michael Lynch told the U.S. Army website. "Unfairly, because it's always assumed the food is bad. Sometimes, it was at that time, and it's always assumed it's the cook's fault. But, when the cook was able to provide hot food, then he became a hero."

As this comment indicates, the popularity of this job could be extremely high but also partially depended on things that were out of the cook's hands, such as the supply lines, which were difficult to maintain during wartime. The C-rations and K-rations the soldiers had to get by on when there was no kitchen within reach were monotonous, heavy to lug around, and occasionally foul-tasting, so it's not hard to see why a decent hot meal could be a nice morale booster.

Cooking skills were also necessary on the homefront, where rationing could severely limit the availability of many food items. The cookbooks custom-designed for the era allowed professionals to help home cooks make delicious meals with what they had, as well as stretch out the various ingredients available to them.

Entertainer

What better way to take a person's mind off things during wartime than a spot of entertainment? A lot of the entertainment industry was affected by World War II and dealt with it in various ways, from making war-themed movies to superstars of the era serving food to soldiers. In the U.S., the Office of War Information was actively working with the industry to harness the popularity of various celebrities and entertainment influencers. Britain also relied on movies, as well as the BBC's radio programs.

Because celebrities were celebrities even during wartime, a particularly popular form of entertainment was the live shows that took many of the era's most famous figures on live performance tours in military camps, factories, hospitals, and other such locations — both home and overseas. Many stars, from Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy to Bob Hope, entertained the troops in such a capacity.

Film star Marlene Dietrich was among WWII's more active troop entertainers. In one no doubt memorable performance for American soldiers stationed in Italy, she found out about D-Day and became the first person to inform her audience of the operation. The crowd, as one might assume, was very happy about the news.