Lies The Netflix Ted Bundy Movie Told You

We would all like to believe that we can spot evil. That's comforting because when we hear stories of people who are tricked into trusting someone who turns out to be an abuser or a killer, we want to be able to tell ourselves that it will never happen to us. That's why Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, the new Netflix movie about serial killer Ted Bundy, is so upsetting. In the film, Zac Efron portrays Bundy the way he was seen by many, including longtime girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer — as charming, and kind, and not possibly guilty of serial murder. If you didn't already know the story of Ted Bundy, Efron's performance might actually convince viewers that you should be rooting for him.

Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile is the second Ted Bundy film by Joe Berlinger, who also brought us Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, a documentary based on actual recordings of Bundy's confessions. So the fictionalized version of Bundy's capture and trial is actually not that far off from the truth, probably because Berlinger was already so intimately familiar with the story. There are a couple of larger inaccuracies and a handful of smaller ones, but for the most part, the story is terrifyingly, terrifyingly real. So don't expect to find too much comfort in this list of the untruths in Netflix's Ted Bundy film.

Movies can't be several years long, so...

Much of what you see in Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile is a condensed version of what happened in real life. A lot of filmmakers do this with "true stories" because life doesn't usually move along at a brisk, fits-into-a-120-minute-movie pace. So in order to tell the story without boring everyone, sometimes events have to be combined or edited down.

In Extremely Wicked, the first of these liberties was taken with Bundy's first arrest, after he was caught with a bag of damning serial killer paraphernalia in the back seat of his car. In the movie, we see Bundy's arrest followed immediately by some interrogation and a scene where Carol DaRonch picks him out of a lineup. It all happens in quick succession, and we get the feeling that the whole thing only took a couple of days. But according to Refinery29, it was a longer process — Bundy was indeed pulled over in August 1975, with handcuffs and some other weird stuff in his car, but they let him go because they didn't have enough evidence to hold him. It wasn't until Bundy sold his car the following month that police finally got what they needed to actually charge him with a crime — and only because they seized the car from the buyer and found some forensic evidence inside that linked him to some of the crimes. DaRonch didn't actually pick him out of that lineup until October.

There were more than two trials

In the film, there is that initial trial for the aggravated kidnapping of Carol DaRonch, followed by a single epic trial for the Florida University murders and for 12-year-old Kimberly Leach, who was abducted, sexually assaulted, and strangled the month after the Florida University attacks. The trial takes place in Miami, and it ends with a conviction and a death sentence. According to Crime and Investigation, Bundy was actually tried three times, with the Kimberly Leach trial being an entirely separate proceeding. The jury returned a guilty verdict, and he received another death sentence.

It's obvious why Berlinger chose to compress the second and third trials — Leach's murder was no less horrific than the others, but kicking the narrative into a whole new trial would have been a little redundant and would have made the film considerably longer, and it was already approaching the two-hour mark. And besides, you'd have to find a new judge, and who wants less John Malkovich in pretty much any movie?

Let's talk about Carole Ann

Ted Bundy and the woman he eventually married, Carole Ann Boone, had a lot of a private conversations that nobody witnessed, which is not super surprising when you think back at all the private conversations you've ever had that no one else witnessed. If they were going to make a movie about your life, they'd have to make a bunch of dialogue up, too. But trying to accurately portray Bundy and Boone's relationship was complicated by the fact that Boone is no longer in the public eye, so it's not like filmmakers could ask for her account of the things that happened between the two of them.

It wasn't just the dialogue that was wrong, though. Bundy did propose to her in court, but it happened at the third trial, not the one recreated for the film. And the timing of her pregnancy is all wrong, too — she conceived during conjugal visits after his conviction, not before.

Boone divorced Bundy in 1986 and moved back to Washington with the couple's daughter and a son from a previous marriage. Some of the people who were acquainted with Boone said she felt betrayed by his eventual confessions — according to People, Boone stopped visiting Bundy during the last two years of his life. After that, it's pretty understandable why she might have wanted to disappear. At that point, it wasn't just about her anymore — she also had a daughter to protect.

There was no scrawled word in the glass

Much of the fictionalization of the Ted Bundy story was done out of necessity, either because events needed to be condensed for runtime or because filmmakers just didn't know the details. But there was one scene toward the end of the film that was totally made up. In the scene, Kloepfer visits Bundy prior to his execution and shows him a photograph of the decapitated corpse of one of his victims. "What happened to her head?" she asks him. Bundy tries to sell her some lame explanation, but she's not having it. Finally, he puts down the phone and with his finger, writes "HACKSAW" in the foggy glass that separates them.

It's a shocking, emotional moment, and it didn't really happen. According to Cosmopolitan, there's no evidence that Kloepfer visited Bundy before his execution, and Berlinger has admitted that the scene is a total fabrication, included in the name of "dramatic license."

What really happened is almost anticlimactic — Bundy's "confession" wasn't really a confession, and it wasn't made in person, either. After his arrest in Florida, he told Kloepfer over the telephone that he was driven by "a force." "I just couldn't contain it," he told her. "I've fought it for a long, long time. ... It got too strong." That's not the same thing as confessing to cutting off a woman's head with a hacksaw, but it's as close as Kloepfer ever got to the truth.

No, a dog did not really freak out in Bundy's presence

Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile is a pretty quality film, mostly free from dumb cliches and random stupidity. But there is that one scene, that one really, really stupid scene, where Bundy and Kloepfer are at a dog adoption center and Bundy crouches down to greet the dog Kloepfer has chosen, and it freaks out, just as one might expect a dog would freak out if it encountered a serial killer in a stupid cliche.

At any rate it will almost certainly not surprise you to hear that this didn't happen in real life. We're not really sure what Berlinger was thinking when he greenlighted this stupid, stupid scene. Maybe he'd just watched the 720th Hollywood production to use that ridiculous device and he felt obligated or something. Esquire says he did it because "animals know," but seriously? Sociopaths don't ever have dogs? Anyway Berlinger evidently felt that Kloepfer's character should only get the most subtle of clues about Bundy's true nature. "When the dog did not get along with Bundy, that's a clue," he said, "but it's not like finding a knife. I did my own interpretation of having some clues along the way."

Jerry wasn't a real person

In the film, Kloepfer is comforted by her coworker Jerry, who is played by Haley Joel Osment from The Sixth Sense. Jerry doesn't see dead people, but he sure as heck sees the dude who made them all dead.

Jerry eventually becomes Liz's protector and confidant, and he tries hard to help her see the truth about her monstrous ex-boyfriend. But according to Oxygen, Jerry wasn't a real person — at best, the character is a composite of a few people Kloepfer knew, though he was likely most heavily based on someone named Hank, who was a one-time romantic interest Kloepfer met when Bundy was loose in Florida. In her biography, Kloepfer says she met Hank at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. "Although we didn't have a lot in common other than our recovery from alcoholism, he made me feel safe," she wrote. "He began to stay with me even at night."

Hank also had a few telephone altercations with Bundy, some of them similar to the one seen in the film. Kloepfer's continued correspondence with Bundy was evidently a point of contention between the two of them, though no one knows how the relationship panned out. As far as we know, Kloepfer didn't marry him.

Kloepfer never mentioned Papillon

In the film, Bundy gives Kloepfer a copy of Papillon, a French novel about a man who has been falsely convicted of a crime. Bundy is super-insistent that Kloepfer read the book, to the point where he repeatedly calls her about it even though she keeps hanging up on him. "It's about this guy who's been terribly convicted of a horrible, horrible crime and he gets sentenced to life," Bundy tells her. "But he didn't do it. He obsesses over the day he'll be free again and spends years hatching escapes ... but he never loses hope. And that's my wish for us, Liz. That we never give up hope." Eventually, Bundy manages to give her a copy of the book as a gift, and at one point she's even seen reading it.

According to Esquire, there's no mention of Papillon in Kloepfer's biography, so this storyline was likely also invented for the film. But it's really a great device because it mirrors what actually happened in Bundy's life, except for the part about being innocent. Filmmakers do love their obscure plot devices, don't they?

Malkovich made the judge slightly dorkier than he actually was

John Malkovich plays Judge Edward D. Cowart, and if his character seems a little bit over-the-top when he calls Bundy nicknames, compliments his attire, and tells him he's good at lawyering, well that's because real-life Cowart actually was a little bit over-the-top. According to USA Today, most of what Malkovich says in this role actually came verbatim from court records, including the strange praise he lavished upon Bundy toward the end of the trial: "You'd have made a good lawyer and I would have loved to have you practice in front of me, but you went another way, partner."

The film's name also comes from something Cowart said during the trial, but not everything we hear coming out of Malkovich's mouth during Extremely Wicked came from court documents. He did improvise a line or two — for example, at one point he admonishes the court spectators, who are actually cheering something Bundy said: "You're not here for the 'Flipper and Friends' show at SeaWorld." It does sound kind of like something Cowart might have said, though, so you've got to give Malkovich credit for knowing his character.

Bundy wasn't really an awesome boyfriend

The film skims past most of Bundy and Kloepfer's life together. We see it happen on an old movie reel, and it seems idyllic — birthday parties, snowball fights, bike-riding lessons with Kloepfer's daughter. What we don't see is the bad stuff, and there was some bad stuff. Contrary to what we see in the film, Bundy and Kloepfer did not have a perfect relationship.

According to Newsweek, Bundy was verbally and emotionally abusive — in her now out-of-print biography, Kloepfer said he would sometimes lock her out of the house, and he once threatened to break her neck after she confronted him about some items he'd stolen. He hit her, too, though Kloepfer said it only happened one time. "It was early in our relationship and I was drunk," she wrote. "I couldn't remember what we were arguing about but I kept telling Ted to 'go ahead and hit me. Go ahead!' Finally he slapped me." But she also denied that he was a violent person. "When we argued he was always calm and reasonable. ... I could count on the fingers of one hand the times that Ted had lost his temper since I'd known him."

Still, there was enough weirdness in their relationship that it's not like she was completely blindsided by the idea that her mostly loving partner might have had a serial killer hobby on the side. He was nowhere near the always-charming guy he is in the movie.

The film left out the part where Bundy tried to kill Liz

When it comes to Ted Bundy and his relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer, one of the things people can't seem to wrap their heads around is the idea that he was with her for so long but never tried to kill her. Part of this comes from the perception people have that serial killers just can't rein in those killer instincts. But that's not always accurate, and it's probably not even mostly accurate. There have been many examples of serial killers who remained in relationships with people they did not try to kill.

Still, if your significant other is a secret serial killer, it does seem like he might actually consider ending an argument by killing you at some point because that's kind of his thing. And Bundy did in fact try to kill Kloepfer once, and he even told her so after he was arrested. According to E! News, Bundy admitted that one night after she'd been drinking heavily, he had left her sleeping on a hide-a-bed in front of the fireplace. Before slipping out, he closed the damper and then put a towel under the crack in the door. Kloepfer might have died from smoke inhalation, but she woke up coughing and managed to clear the smoke and put out the fire. What's most remarkable about that story, though, is not the fact she survived — it's the fact that it was the only time he actually tried to do it.

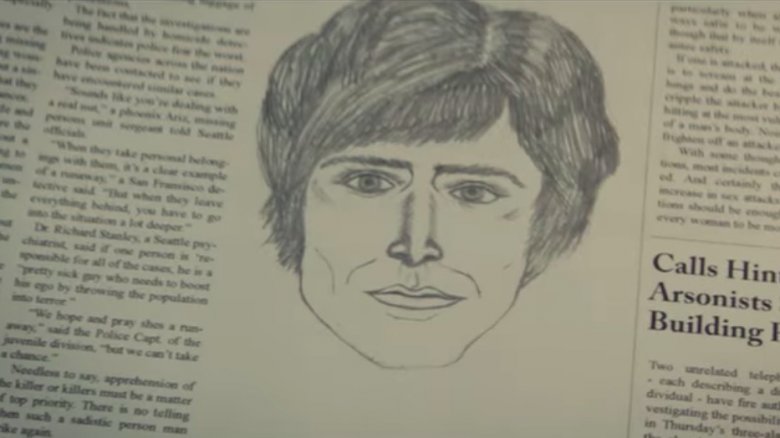

It wasn't just the sketch that made Kloepfer call the police

In the film, Kloepfer says she called the police mostly because of Bundy's physical resemblance to a police sketch and the fact that he drove a similar car. In reality, Kloepfer had more than just that to go on. According to Esquire, Kloepfer found a number of items that seemed to link him to the recent murders and disappearances in the area where the couple was living. She had found plaster of Paris in one of his desk drawers, for example, and police reports said the suspect's arm had been in a cast. She also said he kept a knife in the glove box of her car. "Sometimes it was there; sometimes it was gone," she said in Ann Rule's The Stranger Beside Me. She found women's underwear, too, and a bowl filled with other peoples' house keys.

So yes, there were plenty of clues, and not just those coming from freaked-out animals. And it's almost a relief to hear that because it would be kind of crappy to call the police on your otherwise loving boyfriend just because he kind of sort of looks like some guy in a police sketch. Don't you think?

About that bite mark evidence...

Just so you know, bite mark evidence is kind of a joke. There's also the part where Bundy later confessed to a bunch of murders, so it's not like faked evidence put an innocent man in the chair or anything, but modern forensic science has pretty much rejected bite mark evidence as a credible way to do anything. "To say that Ted Bundy is the source of this bite mark based only on a comparison of his teeth to the impression is a scientifically impossible statement to make," a forensic research scientist told Oxygen.com.

At any rate, Extremely Wicked did get that part of the story correct — the jury was very convinced by the bite mark evidence. What it got wrong was the part where Bundy himself cross-examined Richard Souviron, the dentist who provided the bite mark testimony. It was actually Bundy's defender, Ed Harvey, who tried to discredit Souviron, probably because Bundy knew how critical it was to his defense. "Analyzing bite marks is part art and part science, isn't it?" Harvey asked. "I think that's a fair statement," Souviron replied. But the jury had already bought in, and so it was kind of a miscarriage of justice that ended up condemning one of the world's most notorious serial killers. Uh ... let us know when you've decided how to feel about that.