11 Times The Tolkien Movie Lied To You

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

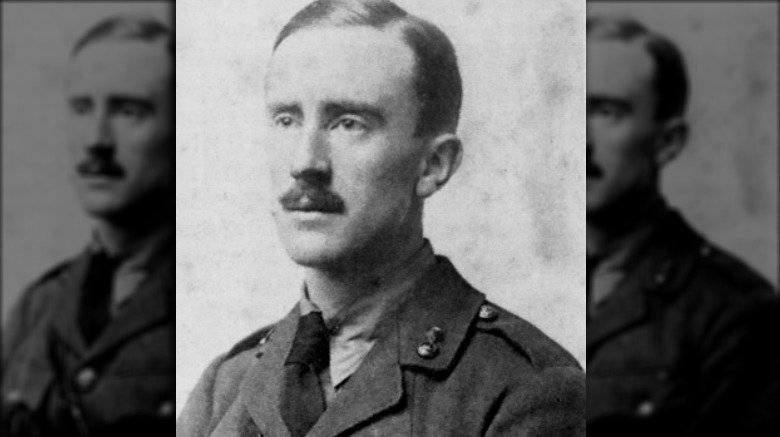

There's no denying the impact J.R.R. Tolkien has had on literature, on fantasy, and on the hearts and minds of countless people. Who among us hasn't dreamed of going on an epic quest surrounded by a close-knit group of friends, fighting orcs and maybe — just maybe — saving the world along the way?

It's all pretty lofty stuff, so it's fascinating to get a glimpse behind the curtain at the man who imagined it all. Sure, he may have been influenced by long-dead languages and mythology from peoples long gone, but he also created such powerful images of elves, dragons, and hobbits that it's become the go-to comparison for fantasy of all sorts. Now quick, what's the most common question an author gets asked?

"Where do you get your ideas from?"

Tolkien tries to answer that, exploring his formative years in school, some of his time as a student at Oxford, and his service during World War I. We see the seeds of his famous stories planted, but as with any biopic, there are some things they just don't get right.

Sugar lumps were important ... just not in that way

Everyone who's ever had a crush on someone knows just how awkward it gets, and in the film, it gets super awkward when Tolkien takes Edith out to a fancy restaurant. At first, she's a little horrified it's such a fancy place — and there she is, without a hat. Clearly, she's not fitting in among all the other fancy ladies, and she's worried. He brushes off her concern, they chat for a little bit, and then out of nowhere she starts throwing sugar cubes at some of the women she was just admiring. What? Why?

There's a strain of truth here. That's actually something they did, but not quite in the context of a fancy restaurant. According to Psychology Today, one of the couple's favorite pre-university pastimes was to head to a rooftop tea house in Birmingham. There, they'd take the sugar lumps out of the bowl and throw them at the people walking below them, particularly those sporting hats. They'd go from table to table throwing sugar, and while that seems like a very strange thing to spend an afternoon doing, you had to get creative in the days before video games.

No, he didn't almost flunk out of Oxford

According to the film, a young Tolkien and his friends get in trouble for hopping on a bus they're definitely not supposed to be hanging out on. But Tolkien has bigger problems, he learns, as he's summoned to the offices of the powers-that-be in Oxford. He's lost his scholarship because of his poor grades and won't be able to afford to stay in school.

But according to the Tolkien Society, he never did quite that badly. For his initial foray into the university system, Tolkien studied Old English, the classics, and Germanic languages. Partway through, he scored a second class degree — which means he wasn't at the top of his class, but he was far from the bottom. (Oxford notes that the current U.K. grading system began in the 1960s, and is made up of, from highest to lowest, a first class degree, upper and lower second class degrees, a third class, an honours pass, and an unclassified honours.)

Tolkien saw his second class degree as pretty disappointing, but it wasn't the end of the world or of his academic career. He did much better in philology — the part of his studies that involved the structure of language — and made the decision to switch from classics to English language and literature. The rest is, as they say, the history of Middle-earth.

He wasn't really that keen on Wagner

The Tolkien biopic is all about suggestion, painting dragons and fantastic creatures into the shadows where an imaginative mind might have seen them and been inspired by them. In spite of some scoffing about just how important the works of Wagner were, the line drawn between Tolkien and Edith's trip to the opera and the appearance of a ring in his most famous work is clear.

Only ... it's not. According to the New Yorker, Tolkien condemned the idea there was any connection between his rings and Wagner's, once saying, "Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceased."

Jonathan Witt, senior fellow at the Discovery Institute's Center for Science and Culture, says that not only are there a ton of magical rings in world mythology, but that it's more accurate to say both Tolkien and Wagner were influenced by the Old Norse sagas, rather than one being influenced by the other. The Independent goes a step further, saying that while we know many of Tolkien's names and languages were inspired by the language, traditions, and stories of old Iceland, the idea to include that magical ring came from a story he was once told. He was visiting an archaeological dig in Gloucestershire when he heard the tale of a ring once uncovered in a field that had previously been the site of an old Roman temple.

There's the ring; no singing needed.

Tolkien and Edith were regular lovebirds from early on

The relationship between the film's version of Tolkien and Edith Bratt was one of awkward childhood glances, teasing conversations, and blushing when their hands touched. But according to Psychology Today, Tolkien and Edith — who were 16 and 19 when they met, respectively — were really good friends almost from the start, and it wasn't long before love was in the air.

They didn't just sneak glances at each other while she played the piano; they got up to all kinds of shenanigans. All that food that was disappearing from the kitchens? That was Edith, piling snacks and treats into a basket Tolkien lowered from his window.

Even though the relationship was discouraged as being improper, Tolkien and Edith were the kind of friends that make amazing, lifelong partners. They talked through the nights, devised a special whistle to communicate, and even arranged to — separately — head out into the countryside on the weekends and meet up once they were out of their guardians' sight. The last straw — the real reason Tolkien's guardian forbade them to see each other until he was 21 — was when they hopped on a train and headed into town to buy each other birthday presents. They were well beyond the coy glances.

You're not my father, I don't have to listen to you!

When Colm Meaney's Father Francis tells movie-Tolkien that he's no longer allowed to see the love of his life, he submits with a strange willingness. Sure, he pouts a bit, but Father Francis isn't his actual father, after all, and he's mostly just around when it's time to pass Tolkien and his brother off to another guardian. Why didn't Tolkien protest more?

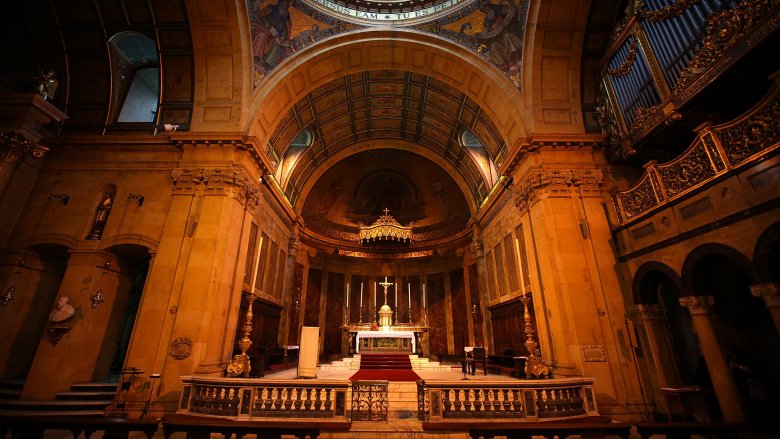

Because that's not the extent of the role the real-life priest played in Tolkien's life, says the National Catholic Register. Tolkien and his mother were devoutly religious, and discovered their spiritual calling at the Birmingham Oratory (above). His mother, Mabel, knew her diagnosis of diabetes was a death sentence at the time, so she appointed Father Francis Xavier Morgan the guardian of her boys. Morgan took his role very seriously and stepped into the shoes of the boys' father. He wasn't just a priest; he also guided their education, took them on summer vacations, secured a suitable home for them, and even paid Tolkien's living expenses while he was at Oxford.

He had such a lasting impact on Tolkien that when his first son was born, he was named John Francis in Morgan's honor. Even after Tolkien started his young family, they would regularly visit and vacation with him, right up until Morgan's death in 1935 — when he willed a portion of his estate to both J.R.R. and Hilary.

He didn't run off to join up

Take the film at face value, and you see a Tolkien who did very much what other young men his age did at the onset of World War I. He's sitting in Oxford when he hears the cries of "War!" and the next thing you know students are celebrating something (the end of the semester?) for a half-second and then Tolkien and his friends are in uniform. But the real-life Tolkien didn't quite answer the call in the same way.

According to the National Archives, war was declared in August 1914. It was almost a full year before Tolkien enlisted, signing up and becoming a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers in June 1915. And contrary to what the film depicts, he wasn't even at Oxford when war was declared: According to the JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia, he was actually on vacation in Cornwall when the news broke.

Why wait? Because, says the Tolkien Society, he wanted to finish his degree at Oxford first, and he did, in spite of the fact his family was pressuring him to enlist. He finished up a first class degree in the same month he ultimately enlisted, but he wasn't immediately sent to the front lines. He spent months in England and was only sent to the front just before the Battle of the Somme, which started on July 1, 1916, and lasted an almost unthinkable 141 days (via the BBC).

The epic goodbye wasn't quite so epic

Every dramatic film has to have that moment. You know the one, the one where it's not clear whether the will-they-won't-they couple is going to get together, or if they're going to be pulled in two separate directions by fate and bad decisions. In Tolkien, he's getting ready to head off to war, ship looming in the background, unrequited love looming over him. But of course, Edith shows up at the last second, things are awkward, then there's a magical kiss, and he has a reason to come back to her. Oh, magical Hollywood, you've done it again!

What is true, says History Daily, is that Edith was engaged to someone else by the time Tolkien turned 21 and could speak to her again. She absolutely did break off that engagement, return her ring, and upset an entire family, but she also converted to Catholicism and married Tolkien — before he went off to war. So he still had a reason to come back, even if it wasn't quite the one depicted in the film. Their marriage lasted 55 years until her death in 1971. Tolkien followed her 21 months later.

There was no one Sam

When movie-Tolkien is in the trenches, he's got someone at his side: a faithful companion who's looking after him, caring for his already-sick self. The man's name is Sam, and the connection is clear — this is the guy who inspired Frodo's loyal companion, Sam Gamgee! But that's sort of a simplification of what really happened, even if it was a decent way to get something close to the truth on the big screen.

John Garth, Tolkien researcher and author of Tolkien and the Great War, did a ton of research into World War I, Tolkien's role in it, and the influences it had on his writing. He turned up a letter written in 1956 to an H. Cotton Minchin, which said, in part: "My 'Samwise' is indeed largely a reflexion of the English soldier — grafted on the village-boys of early days, the memory of the privates and my batmen that I knew in the 1914 War, and recognized as so far superior to myself."

We actually know where the name "Sam Gamgee" came from — and it wasn't one of those batmen. ("Batmen" were essentially officers' assistants.) According to the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, he was actually named after Sampson Gamgee, a surgeon from Tolkien's native Birmingham.

He already knew he had lost his friends

When Tolkien wakes up in an English hospital, the audience can just feel that it's going to be one of those film moments that tests just how much range an actor has. Tolkien is recovering from a nasty case of trench fever on the front lines, and Edith is there waiting for him when he wakes up. But she has some bad news: Two of his best friends have been killed in battle.

But by the time the real Tolkien was sent back to England, he had already known about the deaths of his friends. Rob Gilson died on the very first day of the Battle of the Somme, and according to the JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia, Tolkien had learned this via a letter from Geoffrey Bache Smith, another TCBS member. Tolkien believed from that moment that their boyhood group, the TCBS, was finished.

"My dear John Ronald," he wrote (via Oxford Inklings), "I saw in the paper this morning that Rob has been killed. I am safe but what does that matter? Do please stick to me, you and Christopher. I am very tired and most frightfully depressed at this worst news. ... O my dear John Ronald what ever are we going to do? Yours ever. G.B.S."

Only five months later, Tolkien got another letter. This one was from Christopher Wiseman, telling him Smith had been killed. (The letter he received in the movie really did come ... eventually.)

The opening line that launched an entire journey

"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit."

Everyone knows that line, and we get to see the author write it in Tolkien. But in reality, it wasn't the studied, purposeful bit of writing we see in the movie, with Tolkien inspired to pursue a storytelling career by the final letter written by his closest friend. Instead, Tolkien wrote that first line when inspiration struck him during a very mundane task, no encouragement from his old friend necessary. According to the Collins Dictionary, Tolkien both invented the word "hobbit" and wrote the line while he was grading papers, and it just sort of popped into his head. The term came from the Old English word "holbytla," which essentially means "hole-builder."

According to John McQuillen, curator of the "Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth" exhibit in New York City (via CBS News), Tolkien wrote it without really knowing what it meant. "He had sort of a vision one day while grading examination papers, and just scrawled that line on a blank page, but really didn't quite know what that was supposed to be."

Fortunately he figured it out, and now we all know what a hobbit is.

He didn't have to fight for his friend's recognition

When Tolkien and his friends founded the TCBS, a huge part of what it was about was supporting each other in their literary and artistic endeavors. For some, it was support they didn't find elsewhere. Smith, in particular, wanted to be a poet, but we learn that his parents were less than thrilled about this. After the war, Tolkien takes Smith's mother to the tea room where they spent their days, shows her a collection of her son's poetry, and valiantly entreats her to allow him to publish it. She says no at first, but Tolkien wins her over.

The volume is real, and it's called A Spring Harvest. It's credited to Mr. Geoffrey Bache Smith, is edited by Tolkien, and includes the final version of a poem Smith sent Tolkien while in the trenches. But here's the thing: Tolkien wasn't the one who initiated the posthumous volume. According to the JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia, it was Smith's mother who approached him in 1917 and asked him to do it. Both he and Christopher Wiseman worked on the volume, and it was published in 1918.

It's also worth noting the volume contains two poems Smith wrote in memory of Rob Gilson: "For RQG" and "Let Us Tell Stories of Quiet Eyes" (via the JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia). It gave him the chance to say the words he could no longer speak.