The Most Disastrous Criminal Trials In U.S. History

The ideal American criminal trial is speedy and drama-free, even if it involves sex, money, murder, or all three — not to mention religious, ethnic, and racial animus. But a look at U.S. legal history reveals that the country has had its fair share of legal disasters. When one thinks of a disastrous trial, one cannot help think of a reality TV-type judge show — litigants argue over sex or money, people cheer and occasionally get into fist fights. That is certainly one type of disaster — something America has since at least since the 1875 adultery trial of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher. Then there are the much more serious disasters, ranging from wrongful convictions, like the Salem Witch Trials or the case of the Scottsboro Boys, to incompetent witnesses and prosecutors, as seen in the trial of John Gotti, among others. Here are some moments of America's legal system at its worst.

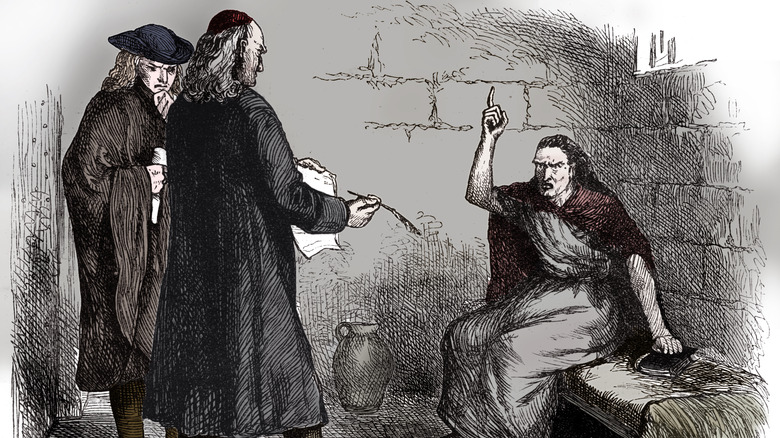

The Salem Witch Trials

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 began in the Colony of Massachusetts when a handful of women started having convulsions ascribed to demonic activity. Three women — an enslaved woman named Tituba, a homeless woman, and an elderly widow — were arrested for witchcraft. Tituba confessed and offered to expose other witches, beginning a free-for-all cycle of accusations and counter-accusations that sent the small Puritan community over the edge — even a 4-year-old girl was not safe from suspicion. As the dragnet widened, people used witchcraft charges to settle personal scores with their neighbors.

Public opinion turned against the trials when Martha and Giles Corey — an upstanding Puritan couple — refused to confess and were executed. Harvard president Increase Mather, his son Cotton, and other clergy condemned the trials' reliance on "spectral evidence" — the accusers' alleged dreams. They insisted a capital crime like witchcraft had to have the same standard of proof as other capital crimes. Dreams by themselves were not proof. If it saved even one innocent person, Increase argued, it was better to let 10 suspected witches escape — one of the first articulations of the American legal standard of presumption of innocence.

Faced with an angry populace, Governor William Phips was forced to disband the court and pay out indemnities to the families of the accused. In a halfway apology, the juries claimed the powers of darkness had fooled them into hysteria. By the trials' end, there had been dozens of arrests and 20 executions, mostly by hanging or being pressed to death with stones.

1980 Washington D.C. jury fight

In 1980, three Washington, D.C., men were tried for armed robbery of several Georgetown students returning from class, illegal handgun possession, and sexual assault by inappropriate touching of the female victim. The city had some damning evidence against the defendants. Police had arrested them almost immediately after the robbery and found the suspects in possession of the victims' belongings. Thus, the case appeared to be a run-of-the-mill criminal trial that would end in a conviction.

After two days of deliberation, the jury still had not reached a verdict. According to The Washington Post, the holdup was reportedly over juror Marian White's refusal to convict the defendants. Since under U.S. law, a jury must be unanimous to convict a defendant in a felony case, White's alleged refusal to convict threatened to send the jury into a third day of deliberation. Furthermore, according to the jury forewoman Anne Wiltse and several of her fellow jurors, White had missed the key evidence against the defendants because she had fallen asleep during the proceedings.

The frustrations boiled over when Wiltse and White got into a brawl in the jury room that included slapping and biting. A federal marshal and the court clerk had to separate them, ultimately placing White in a headlock. The judge declared a mistrial and sent the jury home. The defendants were convicted in a subsequent trial, which was upheld on appeal.

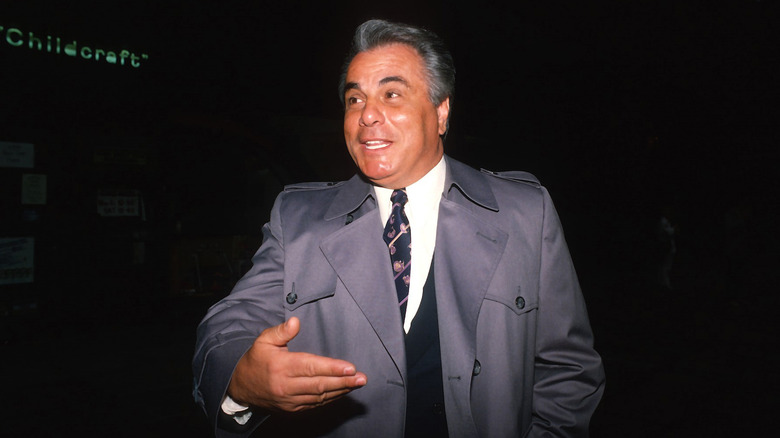

The 1987 Gambino racketeering trial

In 1987, federal anti-mafia prosecutors seemed unstoppable. With the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), they had locked up four of five heads of New York's Cosa Nostra families. Only Gambino don John Gotti was left, and prosecutors were confident their string of informants and strong case would put Gotti and his six co-defendants behind bars.

Instead, the trial was a disaster for the government due to star witness John Cardinali. According to mafia historian Allan May's book "The Last Don," Cardinali nuked his credibility and the prosecution's case by revealing that Washington had paid him $10,000 for his testimony, for which he was happy to "lie, cheat, or steal." He also revealed federal prosecutors had refused his help in busting a major drug operation five years earlier, allowing the defense to argue that the feds were harassing Gotti while ignoring the bigwig criminals. Defense witness Matthew Traynor buried the plaintiffs with salacious accusations against prosecutor Diane Giacalone, claiming she gave witnesses drugs and offered Traynor her underwear for his self-pleasure.

Gotti, meanwhile, had a backup plan. Through Bruno Radonjich, head of the Irish syndicate known as "the Westies," Gotti's men paid juror George Pape $60,000 for a "not guilty" vote. Thus, at worst, Gotti would face a hung jury. Pape voted for immediate acquittal, leading to suspicions Gotti had threatened him — not bribed him, which provided cover for the corruption. The defendants walked, earning Gotti the nickname "the Teflon Don."

The Waukesha parade massacre trial

The trial of Darrell Brooks, who killed six and wounded dozens more – mostly grandmothers and children — with a car at a Christmas parade in Waukesha, Wisconsin, should have been straightforward. Everyone saw him do it and he was caught on camera. But when Brooks fired his public defender, withdrew his insanity plea, and opted to represent himself, observers knew the trial would be far from smooth.

During the trial, Brooks repeatedly picked fights and disrespected Judge Jennifer Dorow, even telling her she had no right to order him around because he was a grown man with grown children — she could only ask him to do something, and he would comply if he wished. He also — among other outbursts — bizarrely went off on one of the prosecutors over the way she said the word "defendant." On the legal side, Brooks claimed to be a "sovereign citizen," arguing the court could not try him because he did not consider himself a U.S. citizen and thus was not subject to American law. Finally, in his closing statement, he claimed that God had willed for the killings to happen, making his conscience clear.

Dorow, who received praise for her poise before Brooks' insolence, tolerated none of his behavior. She repeatedly castigated Brooks and ejected him from the courtroom, forcing him to attend the majority of the trial virtually from a side room. The jury convicted him of murder, for which he received six consecutive life sentences.

The Lindbergh Baby kidnapping trial

Famous aviator Charles Lindbergh's baby son was kidnapped and murdered in 1932, and German-born Richard Hauptmann was tried for the death in 1935. Writer H.L. Mencken called it "the greatest story since the Resurrection," due to the fear and fanfare the case generated. Acquittal was a possibility. Hauptmann's fingerprints were absent from the crime scene and he did not resemble the police sketches of the suspect — the suspect had a distinctive flesh lump on his left thumb, while Hauptmann did not. But amid the circus-like atmosphere, in which vendors sold miniature models of the ladder used in the kidnapping and alleged strands of the Lindbergh baby's hair, defense lawyer Edward Reilly botched the case.

Reilly argued Hauptmann had an alibi and called a motley crew of conmen — each less credible than the last — to testify. The ensuing disaster of contradictory and unbelievable accounts sealed Hauptmann's fate. Bootlegger and thief Elvert Carlson said he saw Hauptmann at a bakery, but could not describe him or any other customer — he only knew the defendant from a newspaper photo. Another witness with multiple criminal aliases said he saw Hauptmann walking his dog at the time of the kidnapping, while a third turned out to be a paid, professional witness.

Unsurprisingly, the jury convicted Hauptmann, who was executed the following year. The likely kidnapper, a man named John Knoll, fled to Germany on a luxury liner with his wife, despite making a deli worker's salary, and died a free man in 1980.

The Kyle Rittenhouse trial

Seventeen-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse was tried for murder for killing two men and shooting a third during the Kenosha unrest on August 25, 2020. He was acquitted of all charges on self-defense grounds at a tense trial that saw prosecutorial misconduct and even MSNBC getting banned from the courtroom for following the jury bus.

The star of the show was prosecutor Thomas Binger, who gave America a lesson on how not to run a prosecution. The judge repeatedly castigated him, most notably for mentioning Rittenhouse's silence after the shooting — his 5th Amendment right — during the cross examination. The prosecution took a further blow when it turned out they had charged him with illegal gun possession despite knowing Rittenhouse was not in violation of Wisconsin law, which only applied to short-barreled rifles under 16 inches long. The judge promptly dropped the charge. Finally, Binger committed a gun safety violation by pointing a closed-bolt rifle at the audience with his finger on the trigger.

The biggest disaster, however, was star prosecution witness Gage Grosskreutz — the third man whom RIttenhouse shot, but survived. Grosskreutz allowed the defense to run roughshod over him, answering with his version of events, only to have the video tell a different story and forcing him to change his story while under oath. In the end, he was forced to admit to running at Rittenhouse with a gun in his hand, strengthening Rittenhouse's claim to self-defense and undermining the prosecution's allegations that Rittenhouse had committed murder.

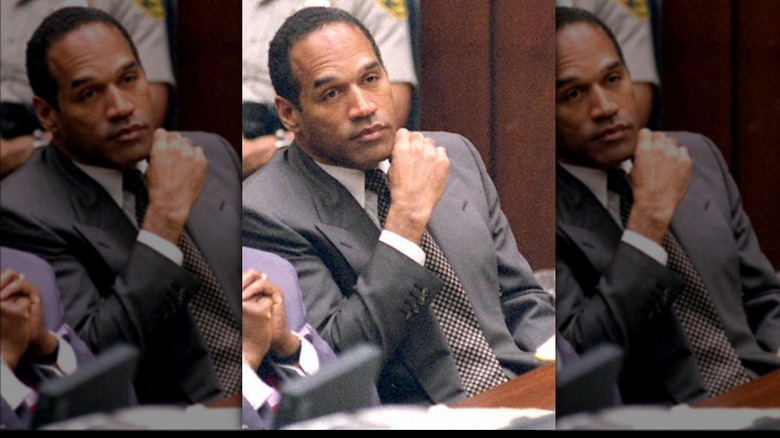

The O.J. Simpson trial

Prosecutors seemed to have an ironclad case against O.J. Simpson, who was tried in 1995 on allegations of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown-Simpson, and Ronald Goldman. They had loads of evidence, from samples of hair that seemed to match O.J.'s, fibers from the gloves he allegedly wore to kill Nicole, blood samples and footprints consistent with O.J.'s blood type and shoe size, and even Nicole's blood on O.J.'s socks. But O.J. walked thanks to prosecutors' slipshod handling of evidence and an investigator's racist statements.

The forensic dispute rested on 1.5 missing mLs of O.J.'s blood. The nurse who drew the blood had not documented the exact amount — a gross oversight for recordkeeping purposes — so he estimated the sample to have been around 8 mLs. But the court only had 6.5 mLs, raising chain-of-custody issues. Thus, the defense argued the blood had been tampered with, perhaps because police had planted it on O.J.'s clothing at the crime scene. The same argument was made for the gloves, which appeared not to fit O.J.'s hands when he tried them on while testifying.

The Fuhrman Tapes sealed the prosecution's fate. Los Angeles Police Detective Mark Fuhrman was recorded multiple times using the n-word while investigating the case, allowing the defense to argue that racist prosecutors were attempting to frame an innocent Black man with murder. When combined with the prosecution's many missteps, Fuhrman's racial bias helped pave the way for O.J.'s acquittal.

The Casey Anthony trial

The trial of Florida mom Casey Anthony, who was accused of killing her daughter Caylee, appeared to be a slam-dunk for prosecutors mostly because it seemed like no one else could have done it. During the trial, however, the defense was able to cast doubt on much of the evidence, which was quite strong, as not meeting the reasonable-doubt threshold needed to convict. From a purely legal perspective, the defense had a point. The hair found in Anthony's car could not be DNA-tested for a match to Caylee, while finds of suspected products of human decomposition in her car's trunk could theoretically have resulted from other processes.

The prosecution's mistake was not using bad evidence, but rather failing to introduce the computer evidence tying their exhibits together — something that shocked even the defense. According to a Local 6 Orlando exclusive, the Orange County Sheriff's Office somehow failed to provide internet search evidence that suggested Anthony had researched how to commit a murder without getting caught. The websites and timing of the searches pointed to her, not her father, and were consistent with the prosecution's timeline of the death.

Had this evidence come out during the trial, prosecutors interviewed by Local 6 said the evidence would have thrown serious doubt on the defense's claim that the death was accidental. Without this evidence, jurors said they had no choice but to acquit — despite being utterly disgusted with their verdict.

The 1944 Sedition Trial

The Sedition Trials of 1944 saw a handful of opponents of American involvement in World War II tried on charges of supporting Nazi Germany, instigating armed revolt against the United States and undermining the war effort. "Dubbed 'sedition and circuses' by some observers and 'Alice in Wonderland' by others," per the Sydney Morning Herald, these trials were a complete farce, exemplified in a picture of defendant Lois Washburn thumbing her nose while leaving court.

The defense's strategy was to stonewall the trial by challenging every single juror. After defendant Edward Smythe tried to flee to Canada, he delayed by constantly arguing with the judge and even his own lawyers. Elizabeth Dilling appointed her freshly-divorced ex-husband as her lawyer so she could humiliate him in court. A third fired his counsel in the middle of the proceedings. When the trials finally began in California, the presiding judge died, resulting in a mistrial.

Outside the courtroom, federal prosecutors found themselves with a PR nightmare. Initially, the public supported prosecution, especially leftist organizations who clashed ideologically with the defendants. But because the feds could not present any evidence of armed insurrection, the public suspected the defendants were charged simply for opposing the war. Thus, leftist organizations incredibly began to lobby on the defendants' behalf, fearing they could be next. In the end, the defendants skated on the most serious charges, but the leaders of the alleged plot were convicted on violations of the 1917 Espionage Act.

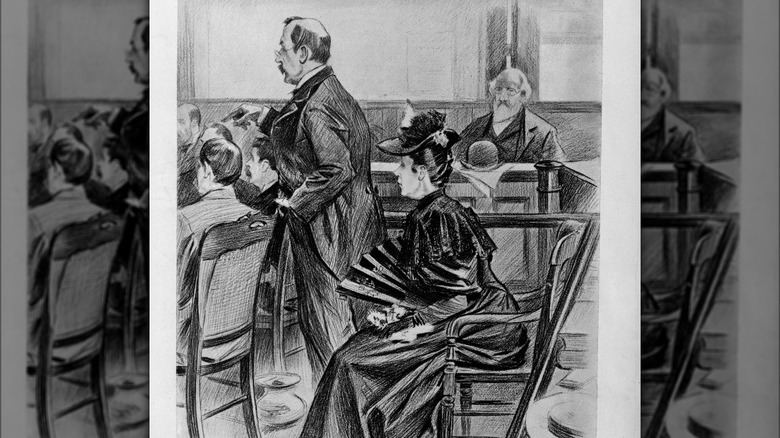

The Lizzie Borden ax murderer trial

Thirty-two-year-old Lizzie Borden was America's original ax murderer, charged with hacking her father and stepmother to death in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1892. The initial evidence pointed to her. Police noted she was not sorrowful about the deaths, her story continued to change, she had attempted to buy the poison prussic acid, and her friend testified she burned the dress she wore the day of the killings. The prosecution, however, failed to take advantage of the evidence because it could not muster up the conclusive proof from the crime scene. The hatchets allegedly used in the killings had no blood on them. Borden's dress had one single drop, which the defense easily shot down. Borden's attempt to buy prussic acid was thrown out on the grounds the substance could be legitimately used — something the prosecution failed to counter.

At best, the prosecution could hope for a mistrial, but had not counted on ethno-religious rivalries that slanted the jury toward the defense. The trial occurred at a time of tension between newly arrived Irish Catholics and founding-stock Protestants in Massachusetts. Majority-Catholic Fall River was excluded from the jury pool, meaning the jurors were mostly drawn from the heavily Protestant rural areas of Bristol County. Borden's defenders in the press claimed that a Catholic male immigrant must have killed the Bordens — a wealthy, respectable Protestant female Sunday school teacher would never do such a thing. The jury agreed and acquitted her in an hour.

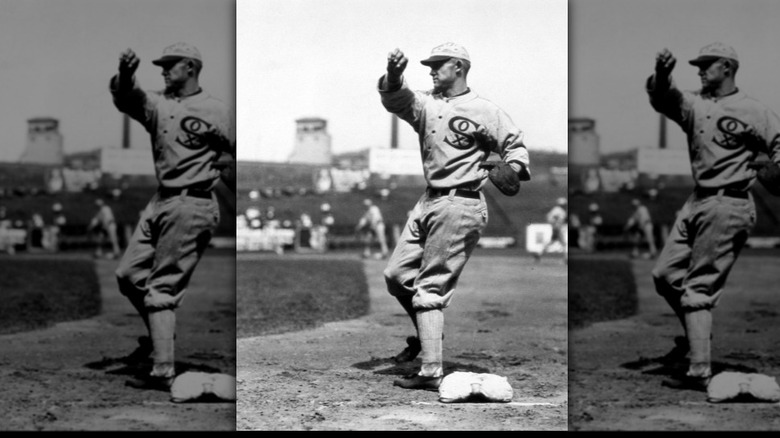

The 1921 Black Sox trial

Following convincing testimony from baseball fixer Billy Burns, the prosecution in the 1921 Black Sox trial — the trial of eight Chicago White Sox players accused of throwing the 1919 World Series — seemed destined for a victory. But the prosecution scored a spectacular own goal by trying to introduce three player confessions the defense alleged had been coerced. After a swearing and shouting match in the courtroom, the judge allowed redacted versions to be read before the jury. This proved a mistake. Not only did the confessions not change anything — they weren't anything new — they froze the prosecution's momentum by boring the jury to death.

Feeling they were losing the jury, prosecutors canceled their remaining witness testimonies against most of the gamblers charged in the fix and focused on convicting the players, who were set to testify toward the trial's end. In response, the defense kept them off the stand. The prosecution not only lost the opportunity to rebut their defenses, it also gave the defense an opening with the jury. In its closing statement, the defense asked why Illinois was targeting underpaid baseball players while ignoring the big gamblers and fixers, whose charges were dropped. The argument no doubt resonated with the working-class South Side Chicago jurors, who viewed the players — all of working class origin — as their social kin. They acquitted the players of all charges and went off with them to an Italian restaurant to party it up into the early hours of the morning.

1970 Marin Civic Center hostage crisis

The 1970 trial of California felon James McClain began as a run-of-the-mill appeal. His lawyer Thomas Bruyneel told the San Francisco Chronicle he expected his client to walk from an assault charge against an Oakland police officer. Instead, he died in a shootout after a gunman named Jonathan Jackson, armed with a full auto carbine, took the courtroom hostage.

Jackson's motive was to get his brother George, who had been involved in the killing of a guard at the Soledad Correctional Facility, out of prison. To this end, he took presiding judge Harold Haley and three female jurors hostage, put a stick of dynamite on the judge's neck, gave McClain and two other felons guns, and attempted to escape in a van. He hoped that the state would negotiate for the hostages' freedom – a condition of which would be the release of his brother.

As the van started to move out of the parking lot, events became fuzzy. According to Marin County Inspector Ron Retani, cited in The New York Times, one of the felons aimed a weapon at officers, who returned fire at the van. In the confusion, Judge Haley, McClain, Jackson, and a third felon named William Christmas were killed. Juror Maria Graham was shot in the arm. Months later in October, domestic terror group the Weather Underground (aka the Weathermen) bombed the civic center in revenge for Jackson's death. In the wake of the shooting, California politicians called for tighter gun laws.

Henry Ward Beecher's 1875 adultery trial

Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, brother of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" author Harriet Beecher Stowe, was charged with committing adultery with his best friend Theodore Tilton's wife, Elizabeth. Now, Theodore and a handful of women — mostly suffragettes – already knew about it because Elizabeth had confessed. But once Victoria Woodhull publicly broke the affair in the Brooklyn press, Tilton took Beecher to court in 1875.

The atmosphere around the courtroom was a circus. Outside, vendors sold black market trial tickets, people got into fights over spots, and according to The New Yorker's Robert Shaplen, at least 3,000 spectators were turned away for lack of room. The courtroom itself was like a theater and the trial, a play. The first and last months were dedicated to flowery opening and closing statements, full of references to all the greats of Classical and English literature (e.g. William Shakespeare) and the Bible, to thunderous applause from the spectators. During witness examinations, spectators hissed or applauded witnesses, depending on whether they were team Beecher or team Tilton. In this reality TV-like atmosphere, Brooklyn police made multiple arrests for disorderly conduct.

The spectacle ended with a "not guilty" verdict. Spousal immunity laws forbade Elizabeth from testifying against her husband and mentioning her confession of adultery. When she tried to present a statement, the judge refused to read it. Theodore testified, but was forbidden from discussing private spousal communications, so the jury never heard his sworn testimony of his wife's confession, allowing Beecher to skate.

The Scottsboro Boys

The Scottsboro Boys trial involved nine Black teenagers who were accused of raping two young white women on an Alabama train in 1931. In the initial trials, eight were convicted and sentenced to death, while a ninth faced life in prison due to his age, despite glaring inconsistencies and due process violations.

From the beginning, the defendants were denied counsel of their choice and forced to go on trial before all-white juries in a selection process that excluded local Black people. They were convicted primarily on the women's testimony, which alleged they forced several young white men off the train at gunpoint and raped the women. Doctors, however, said neither woman showed signs of sexual assault — only sexual intercourse, suggesting any sexual activity that day was consensual. Furthermore, one of the women, Victoria Price, was known to work as a prostitute. And according to one witness, Price, who lived in one of the poor, racially integrated parts of Scottsboro, was not racially discriminatory in her clientele. But given the emotions triggered by the alleged crime's nature, all-white juries unsurprisingly convicted the defendants every time.

The Supreme Court overturned the guilty verdicts on due process grounds, but the Scottsboro Boys were convicted in a retrial, leading to a campaign for their pardons. Charges were dropped against four of the defendants in 1937. By 1976, four more were dead, leaving only Clarence Norris to receive a pardon — ironically from one of Jim Crow's biggest champions, Alabama Gov. George Wallace.