These Were The United States' Plans If Japan Hadn't Surrendered In WWII

Today, with decades of history at our backs, it may seem like the end of World War II was a foregone conclusion. After all, by early August 1945, the Axis powers in Europe had been defeated. With some of its most important supporters left reeling, surely Japan would soon surrender and the war would be over. But military strategists weren't quite so sure. The Battle of Iwo Jima had made Japan's drive to keep fighting painfully clear. When U.S. forces attempted to take the small Japanese island and its strategically important air base in February 1945, the operation took over a month, included brutal hand-to-hand combat, and produced staggering casualties — about 22,000 deaths for Japanese soldiers and 24,503 for U.S. personnel.

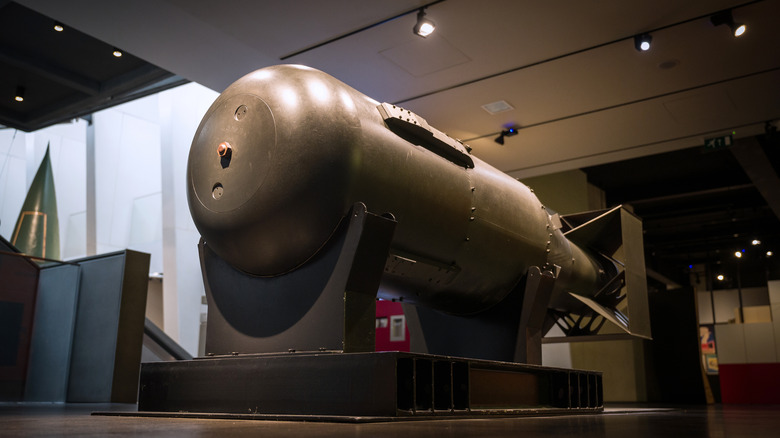

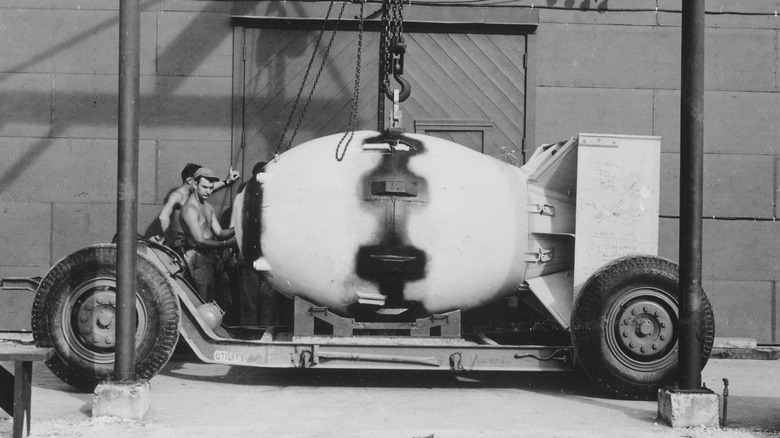

For some, the only way to end the war once and for all was to use the terrible power of nuclear weapons. So, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, followed by another deployed against Nagasaki on August 9. The strikes killed an estimated 120,000 people, with many more succumbing to the effects of radiation sickness in the following weeks and months. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito publicly surrendered.

But, what if the more hawkish figures of Japan had prevailed and the nation did not capitulate, even after this blow? U.S. military strategists had already thought of this. Here's a look at some of their plans to deal with a resistant Japan in the waning days of World War II.

An immediate round of more nuclear weapons wasn't assured

In the face of continued Japanese resistance, the obvious answer, at least to some minds, was to lob more nuclear weapons against the enemy. Yet even high-ranking U.S. officials weren't so sure that this was such a good idea. For one, Truman was reportedly reluctant to order the use of another bomb. According to a diary entry written by Commerce Secretary Henry Wallace, in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman told his cabinet that he had forbidden any further bombing for the moment, in part because he was bothered by having ordered the deaths of "all those kids" and hundreds of thousands of other Japanese citizens (via Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists).

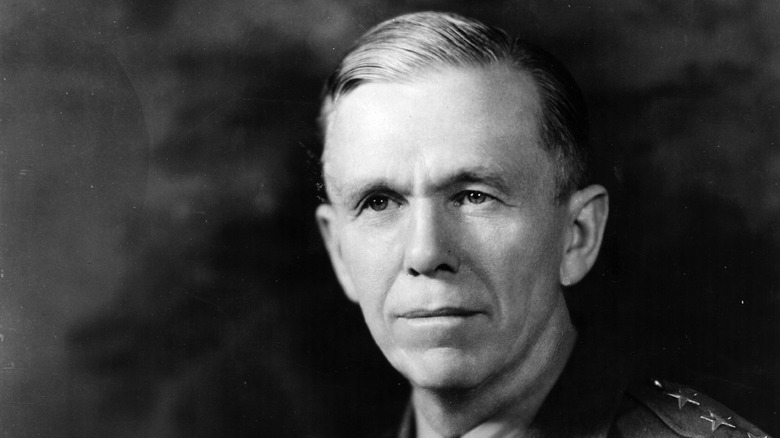

Meanwhile, General George C. Marshall was skeptical about the utility of more nuclear strikes. As a staff member told a representative from the Manhattan Project, Marshall argued that, if Japanese officials wouldn't surrender after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, further nuclear strikes would be unlikely to convince them otherwise. However, he did inquire about the use of nuclear weapons to support a ground invasion of Japan, which was codenamed Operation Downfall.

On another occasion, General John E. Hull also expressed skepticism about further nuclear attacks in an August 13, 1945, call with Colonel L.E. Seeman, saying, "Two of them have had a tremendous effect on the Japanese as far as capitulation is concerned. The next one won't be effective in that respect" (via National Security Archive).

Nuclear attacks weren't out of the question

While quite a few people were wary of sending out another nuclear attack against Japan, neither was it clear if the two strikes already levied against the nation were enough to bring about surrender. A telephone conversation between General John E. Hull and Colonel L.E. Seeman (who was an assistant to Manhattan Project army officer General Leslie Groves) reveals that the two discussed a third nuclear weapon that was to be produced by the Manhattan Project.

The third bomb would be ready for a late August deployment, if Truman ordered as such. Hull and Seeman also discussed how many more weapons could be produced by the Manhattan Project in the coming months, despite Hull's skepticism that further strikes would push the Japanese any closer to surrender (via National Security Archive).

Even Truman, haunted as he reportedly was by the many Japanese deaths after the bombings, reportedly had to consider another nuclear strike anyway. As British diplomat John Balfour wrote to his nation's Foreign Office on August 14, 1945, the lack of an official Japanese surrender at that point was pushing Truman to a dreaded conclusion. As he claimed, "... the President remarked sadly that he now had no alternative but to order an atomic bomb to be dropped on Tokyo" (via "The End of the Pacific War: Reappraisals"). The next day, however, Japan's Emperor Hirohito announced his nation's surrender, the U.S. accepted, and World War II was effectively over.

Nuclear weapons production would have increased

Even if some key officials weren't keen on deploying nuclear weapons straight away, they may have been somewhat more motivated to keep a few bombs on hand for future use. In an August 13, 1945, phone call between General Hull and the Manhattan Project's Colonel Seeman, Seeman told Hull that it would take about 10 days until a new bomb would be ready for deployment. He also told Hull that the Manhattan Project could probably average three new nuclear weapons per month, at least if they were given enough warning.

Nuclear weapons weren't just designed and prototyped at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos facility in New Mexico. They were also assembled there, including the process of shaping uranium and plutonium into the button-shaped nodes that were key components in the final bomb. On a broader scale, booming American war production supported the development and transport of these potential weapons beyond the confines of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos facility. The majority of Allied equipment was American-made, after all, including hundreds of thousands of planes, 2 million trucks, and 17 aircraft carriers.

Japan may have been hit by more intense firebombing campaigns

If the immense and destructive power of nuclear weapons was enough to make President Truman and many other U.S. military officials pause, they may have instead fallen back on established precedent and unleashed other types of bombs on a surrender-shy Japan. But just because the weapons weren't equipped with nuclear firepower didn't mean they weren't also incredibly destructive.

By some metrics, conventional bombs were even more damaging than what was detonated in the skies above Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The earlier U.S. firebombing campaign that targeted Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945, was so destructive that it killed an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 (or perhaps even more) Japanese people. Another million were left homeless after the resulting firestorm reduced their wooden structures to smoldering ruins. Other firebombing attacks throughout Japan took thousands more lives.

Truman acknowledged the terror of the Tokyo firebombing campaign as well as the continued strength of Japanese opposition in its aftermath, saying, "The firebombing of Tokyo was one of the most terrible things that ever happened, and they didn't surrender after that although Tokyo was almost completely destroyed" (via National Park Service). The president and other military officials may have concluded that such bombs weren't going to definitively end the war, but that didn't preclude their use, such as clearing a path for ground troops in a land invasion of Japan.

The US teamed up with the Soviet Union in Asia

The United States wasn't the only member of the Allied forces beginning to move against Japan in 1945. That year, with the fall of Axis powers in Europe, the Soviet Union began to turn its efforts toward the Pacific theater of the war. At the February 1945 Yalta conference, held with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union agreed to join in the fight against Japan soon after the surrender of Germany.

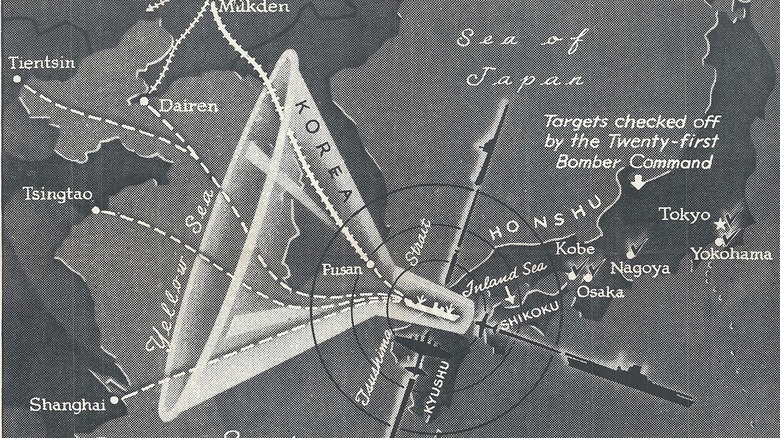

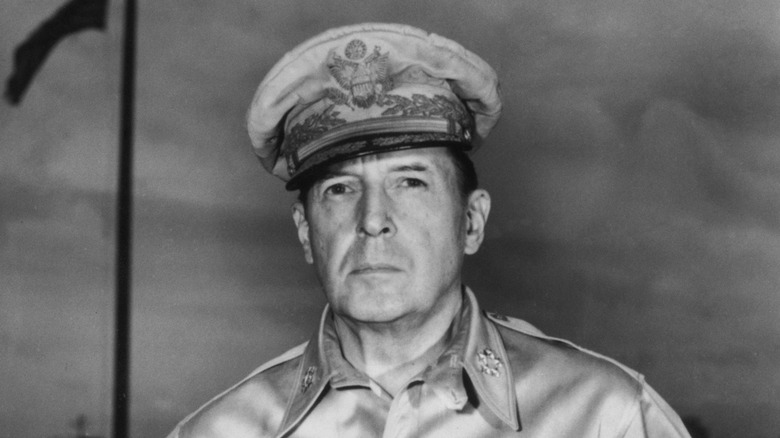

More specifically, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur expected the Soviets to engage with Japanese forces in the occupied Chinese territory of Manchuria. Soon after that, the Americans would commence an invasion of the home islands of Japan. On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union did just that, declaring war on Japan. Almost simultaneously, Soviet forces began their attack on Manchuria.

At that point, President Roosevelt had died and Harry Truman had taken his place. Truman met with Stalin and Churchill at the July 17-August 2, 1945 Potsdam Conference. There, after speaking with Truman, Stalin learned that the U.S. had a new and very powerful weapon on its hands, though the president didn't necessarily specify that the U.S. had nuclear capabilities (Stalin almost certainly knew about the Manhattan Project anyway). That surely made Truman's threat of "prompt and utter destruction" levied against Japan, per the Potsdam Declaration, sound like something far more serious than performative chest-thumping.

An invasion of Japan was in the works

To many Allied strategists, a land invasion of Japan was practically inevitable. But the prospect of sending thousands of Allied troops into Japan wasn't exactly pleasant. Even small territories were only taken by the U.S. after great effort and many casualties — an estimated 13,000 U.S. service members were killed in the struggle for control of Okinawa, representing about 35% of the forces sent to the small, outlying island. That bloody toll was foremost in Truman's and others' minds, as they all predicted a land invasion of Japan's home islands would produce at least as many casualties as on Okinawa, if not far more.

While these projections did not include Japanese deaths, many assumed those numbers would also be staggering. Truman was therefore reluctant to order a land invasion, writing: "My object is to save as many American lives as possible but I also have a human feeling for the women and children of Japan" (via National Parks Service).

Still, a scheme for a ground invasion had been put in motion. The "Reports of General MacArthur," printed while MacArthur was in command of Japan and submitted to the Army in 1953, outlines those plans, now widely known as Operation Downfall. The operation, intended to target the islands of Kyushu and Honshu, was conceived in early 1945. Broken into two phases — Olympic for the first attacks on Kyushu, followed by Coronet to target Honshu — Operation Downfall was slated to begin in December 1945.

Poison was considered on multiple fronts

The use of poison in various forms was also suggested as part of an assault on Japan. This could have taken the form of an herbicide applied to rice crops, though this wouldn't have been feasible until after the start of the land invasion, and the rice may have been needed to feed Allied troops. Moreover, millions of Japanese could have died, given that rice was a central food source in a nation that was deeply food insecure by 1945. However, this strategy could have been reconsidered if the invasion of Japan ground on for an extended time.

General George C. Marshall also pushed for the use of poison gas, though he told Truman that it would only be used against surrounded combatants who would not surrender. Marshall argued that gassing Japanese soldiers would spare the lives of U.S. personnel, compared to sending them in to confront Japanese forces face to face, as had happened in Iwo Jima.

However, Truman refused to give the go-ahead for the use of gas. His argument was based on a precedent established by President Franklin Roosevelt, who said he would only allow the use of gas if the enemy deployed its own poison gas attacks first. Yet, there is no indication that this particular weapon was completely off the table. If a land invasion proved difficult or the mounting number of casualties began to weigh heavily on commanders, Truman may well have been persuaded that gas attacks were a necessary evil.

Other countries would have likely participated in an invasion of Japan

While the U.S. broadly expected the Soviet Union to keep things occupied in the Japanese-held Chinese region of Manchuria, they hardly planned to conduct a land invasion alone. By July 1945, the British Chiefs of Staff had outlined military campaigns of their own that were meant to retake parts of southeast Asia and Singapore, known as Operations Zipper and Mailfist. However, some officials worried that these plans weren't enough. If there wasn't a significant British presence in Operation Downfall, would the U.S. attitude towards one of its allies turn sour? And how would Asian nations feel about Britain strolling back in after the war, trying to manage territories after having done little to actively push invading Japanese forces out?

So, though U.S. General Douglas MacArthur was to oversee Operation Downfall and the whole operation was to be completed with American oversight, it was also agreed that British soldiers would take part. To this end, British troops were set to switch out for some of the American divisions that had already been marked to invade Honshu in Operation Coronet.

Additionally, other soldiers from parts of the Commonwealth would join in the land invasion, including those from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. British divisions would be able to keep their own uniforms, but for simplicity's sake, they would all be given American weapons and other supplies before the invasion commenced.

The US would have continued to blockade Japan

By the summer of 1945, the U.S. Navy had already established a blockade of Japan. If Japan hadn't surrendered, the U.S.'s plans included intensifying this strategy, which had the potential to kill millions of people by cutting off material and food supplies to a nation that had long depended on imports.

Japan had already been experiencing these difficulties for years, as President Roosevelt had shut down U.S. exports of steel and oil to the nation after Japan's December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Goods from Japanese territories in the Pacific were likewise cut off, largely by U.S.-laid mines and submarines patrolling nearby waters. As the war ground on, this blockade became all the more aggressive as the U.S. military produced more weapons, craft, and soldiers. By 1945, the blockade had caused Japan's imports to slow to a mere trickle.

What American strategists didn't necessarily know was that Japan's agricultural sector was already in dire straits. Rice crops did poorly in 1945, meaning that a blockade that halted food imports could have been even more deadly. Plans to attack the country's rail system would have exacerbated the growing problem. Strikes on the rail infrastructure, which was already limited, would have made it even more difficult to move rice around the country to hungry Japanese citizens. During the war, shipping goods from one region of Japan to another along the coasts of the islands was also all but impossible due to the blockade.

MacArthur expected a long-haul occupation

Given the resistance Allied forces encountered in Japanese-held territories like Iwo Jima and Okinawa, commanders expected opposition on the main islands of Japan to be at least as fierce, if not more so. Beyond what could have been considerable casualties on both sides, this was also expected to spell a long and arduous occupation.

General MacArthur, who was the Allied commander of Japan from 1945 until 1951, predicted that occupation after a land invasion would be a grinding slog. He expected a decade or more of trying to control Japan after a military invasion, made all the more difficult by the possible presence of guerrilla fighters, especially in rural areas.

Still, though it was widely assumed that Japanese people at the time thought they were winning, or at least could still prevail in the face of Allied encroachment, there's evidence that higher-ups in the Japanese military were less optimistic. While the Allied forces were planning Operation Downfall, Japanese officials had made the reasonable assumption that an invasion of their nation was in the works and would likely start on Kyushu, then move onto Honshu towards Tokyo. In response, some planned suicide attacks, or at least initiatives that would have amounted to such — civilians with sharpened bamboo poles could not have expected to fare well against American artillery. Yet others, including Emperor Hirohito and his advisors, pushed for a far less bloody diplomatic solution, even if it meant battling recalcitrant officials and finally admitting defeat.