The Final Words Of Theodore Roosevelt Explained

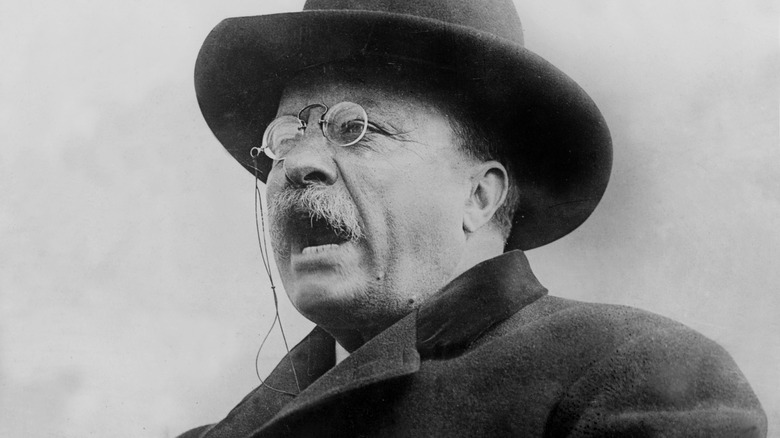

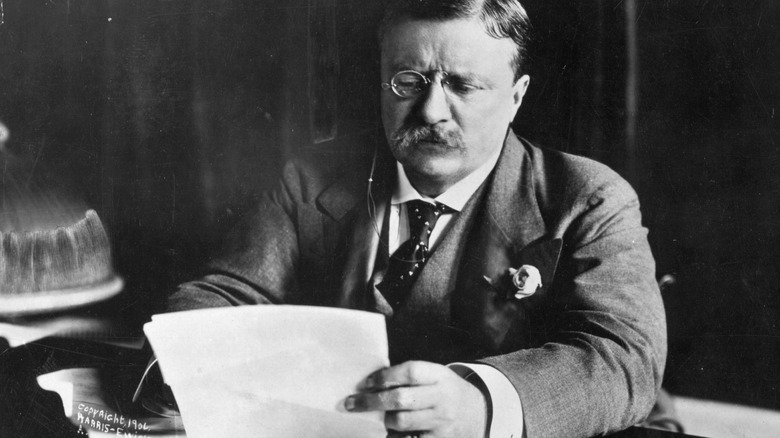

When Theodore Roosevelt died in his sleep on January 6, 1919, one commentator remarked that sleep was the only time that death could safely come for the former president. If it had come while Roosevelt was awake, there would have been a fight. It was one last tribute to the famed energy and determination of "Teddy," the rough-riding, trust-busting, national park-creating champion of the progressive movement of the early 20th century.

That energy was fading by the end. Roosevelt was an early critic of American neutrality when World War I broke out, and when America finally entered the war on the side of the Allies as he'd hoped, he was willing to head up a cavalry regiment. It wasn't to be, but his sons all served in the war, all of them brought up with their father's ideals of courage, honor, and a willingness to sacrifice. But the death of his youngest son, Quentin, to German air fire, left Roosevelt crushed.

Grief didn't do any favors for his health, which was finally collapsing after years of living vigorously. He was hospitalized for seven weeks with gout in 1918. While still active in politics, Roosevelt's energies began to lag, and he took to visiting the family stables, lamenting his lost son. In that state, he wasn't ready with rousing, death-defying last words. On January 6, 1919, he asked his valet (per The New York Times), "James, will you please put out the light?" The lights put out, Roosevelt drifted off to sleep and died of a pulmonary embolism.

Roosevelt was planning to run for president again

Tired, ill, and heartbroken though he was by 1919, Theodore Roosevelt wasn't done fighting yet. Almost as soon as he pledged not to run for a third term as president in 1904, he had second thoughts. Even after the election of 1912, in which Roosevelt split the Republican Party and ran second to Woodrow Wilson, he wasn't willing to give up on dreams of taking back the White House. His frequent attacks on the Wilson administration ran past the point of sense — the two of them shared a progressive view of government and an interest in constitutional reform. But the two men loathed each other, and Wilson was happy to deny Roosevelt the chance to become more involved in World War I.

Roosevelt remained a harsh critic throughout the war. Privately, he was acidic about Wilson as a man; publicly, he railed against the administration and such policies as the Fourteen Points. His frequent attacks have been credited with helping the Republican Party retake Congress in the 1918 midterms. They also helped him reconcile with the conservative wing of the Republican Party. Roosevelt had no intention of softening his progressive ideals, but he was happy to have consolidated support ahead of the next election.

That election was scheduled for 1920, and Roosevelt was considered the frontrunner for the Republican nomination. He gave speeches endorsing a range of progressive reforms and wrote to a friend that he wished "to make the Republican Party the Party of sane, constructive radicalism, just as it was under Lincoln" (per Nathan Miller's "Theodore Roosevelt"). He was working on party messaging when he died.

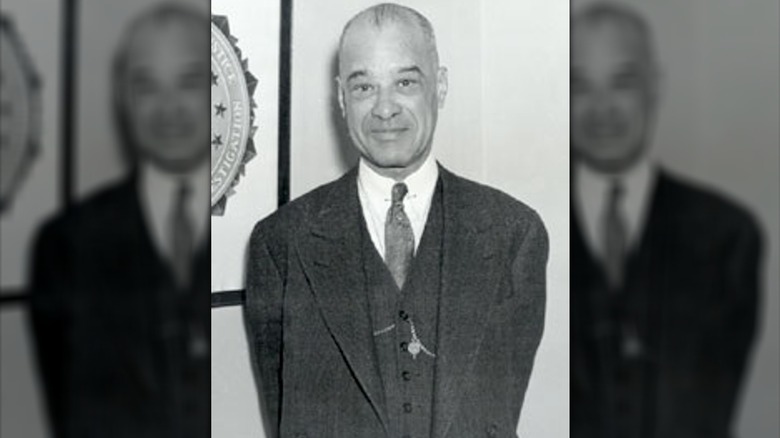

The valet who heard his last words became an FBI agent

The valet who heard Theodore Roosevelt's final words had been with him for years. James E. Amos was a native of Washington, D.C., born to a former enslaved person-turned-policeman. It was his father who got Amos his first job with the Roosevelt family — he was on duty at Rock Creek Park when he happened to meet the president and brought up his son's need of direction. Amos was first hired to watch the Roosevelt children, something many who came before him hadn't been able to handle. Amos not only managed the rowdy brood, he won the president's confidence. He became a butler and valet to Roosevelt, both at the White House and at his private home in Sagamore Hill.

Working directly under Roosevelt's wife Edith, Amos oversaw the family business, kept Roosevelt from overdoing it, and became a close companion who shared theater, literature, and guns. Though he left the Roosevelts in 1913 to seek better wages, he remained on good terms with the family and was regularly called back whenever they needed him. And of course, he was the person Roosevelt asked to put out the light on January 6, 1919.

A crack shot who spent time as a detective while away from the Roosevelts, Amos joined the FBI soon after his old boss's death (with a reference from the former president). He served there from 1921 to 1953 and had a hand in breaking up Murder Inc. and a Nazi spy ring. He died the same year he retired, at 74.