Things That Turned Out To Be Fake On Antiques Roadshow

The basic premise of "Antiques Roadshow" rests on the idea that you might have something of intense value quietly sitting in some forgotten corner of your attic or gathering dust on a mantelpiece. That's surely what motivates the 3,000 or so people who bring their objects to a taping of the American version of "Antiques Roadshow," or the estimated 4,000 who arrive at a filming of the BBC version. Either group can expect to wait in long lines, hoping to meet with an expert appraiser who will tell them that they own a unique and very valuable piece. Yet, not every item will turn out to be gold, literally or figuratively. Some are everyday objects that, while they may hold personal significance, are unlikely to fetch much at market. A few are even outright fakes.

It's not that all guests in possession of a fake antique are out to deceive the show's appraisers. Instead, these fakes are more likely to be cases of mistaken identity, especially if a buyer is unaware of the market for fakes when it comes to especially prized goods like Tiffany lamps or American Federal furniture. The problem is so rampant that the BBC version of "Antiques Roadshow" now routinely airs a rogues gallery segment that features commonly faked items like African tribal art and designer watches. Perhaps some of these "Antiques Roadshow" guests now wish they had seen one of these segments before putting down their money for what turned out to be a dud.

Olmec figure

A guest on a 2006 episode of "Antiques Roadshow" on PBS was perhaps hoping that the large stone sculpture his parents kept as a poolside decoration was a piece of ancient Mesoamerican art. It certainly looked like it and, as the guest claimed, testing showed that it hadn't been made with the help of modern tools. But appraiser John Buxton likely only had to take one look at the piece to shoot down any hopes that it was an ancient and highly valuable example of Olmec art.

That's because, when it came to style, the carving was little more than a dud. "Olmec has great balance," Buxton said. "It's tight, it's elegant, and this piece is not that" (via PBS). While he appraised the piece for up to $2,500 as decorative art, he delivered one more blow. He told the owner that, if it had really been Olmec, it would have been worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Olmec art, produced in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico between 1,200 B.C. and 400 B.C., is highly regarded for its fine detail and use of jade, volcanic basalt, and skillfully crafted ceramics. The most famous examples of Olmec art are astoundingly large carved heads, many of which were crafted in San Lorenzo in what's now the state of Veracruz. The largest of those monumental heads stands at nearly 10 feet tall, making them especially difficult to cart off to a taping of "Antiques Roadshow."

Jacob Weber box

At first, things must have looked just fine during an episode of "Antiques Roadshow" filmed in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. Appraiser Wes Cowan told a guest that he had a small art piece that had been painted by folk artist Jacob Weber. For a random discovery in an antique shop, the little wooden box bearing the image of a two-story, dark-roofed home was quite the find, especially considering the man's grandfather had paid $1,000 for the piece. Cowan appraised it for $10,000 to $15,000.

Jacob Weber was a cobbler working in 19th-century Pennsylvania, but today he's best remembered for his small decorated containers that often sport intricate floral designs or simplistic but striking images of houses. For many, Weber's collection of painted boxes exemplifies early American folk art.

But things took a turn after the episode aired in early 2016. Another antiques dealer saw the episode and contacted Cowan about some concerning details that he had spotted. The hinges were all wrong, for one. Other boxes that were confirmed to have been painted by Weber had projecting bases, not ones that were even with the sides as in the "Antiques Roadshow" piece. Cowan agreed that he'd made a mistake, and PBS published a correction on the "Antiques Roadshow" website. The box's new value? A mere $100 to $150.

Grotesque face jug

To be fair, this piece represents a case of mistaken identity more than outright fakery, but it remains one of the most striking missteps made by an "Antiques Roadshow" appraiser. That's in part because the object in question, described as a grotesque face jug, is truly outlandish. Seen in a January 2016 episode, the ceramic vessel sports a variety of twisted faces, a stitched-shut eye, and other distorted features. Appraiser Stephen L. Fletcher said that he believed it was part of a grotesque face jug tradition from either the Mid-Atlantic states or farther to the south from the late 19th to early 20th century. The guest was understandably bowled over when Fletcher appraised the jug at $30,000 to $50,000.

Soon after the episode aired, however, a viewer sent in a tip that the six-faced jug was actually made by her friend Betsy Soule. When "Antiques Roadshow" got a hold of her, Soule confirmed that she made it while in high school in the 1970s. The vessel's newly appraised value plummeted to $3,000 to $5,000. At least Fletcher was highly complementary toward Soule's work, saying that the jug "was modeled or sculpted with considerable imagination, virtuosity, and technical competence" (via PBS).

Surprisingly enough, Alvin Barr, the guest who brought the jug on "Antiques Roadshow" in the first place, was also relieved when its value dropped. "I hated it when it was $30,000 to $50,000, because who wants $30,000 to $50,000 lying around their house?" he told The Bulletin.

Block front chest

Block front cabinets are linked to Boston furniture craftsmen beginning in the mid-1700s, who created the curving forms of the furniture as a way to appeal to the spendy tastes of upper-class clientele. This style not only required solid pieces of wood but also extra time and a high level of skill. Each piece of genuine block front furniture had to be carefully shaped by hand by master craftspeople.

Too bad for the guest who appeared on "Antiques Roadshow" in 2013, believing they had just such a piece of finely crafted furniture. Appraiser Leslie Keno had to break the difficult truth: The chest was a fake. He noted that the initial shape and fixtures seemed right but continued to point out a series of increasingly suspicious flaws. Pulling out a drawer, he explained that the dovetail joints and other segments of the interior were actually stained to appear darker, mimicking the oxidation that would be seen on genuinely old wood. The same effect was spotted along the bottom of the cabinet. And whoever had made the fake had used poplar as a secondary wood; however, Keno noted that real Boston furniture makers would have been far more likely to reach for white pine instead.

Keno said that a real block front chest would have brought in $30,000 to $50,000, or even $75,000 for an especially nice one. The fake? Just $3,000 to $5,000 — at least it was enough for the guest to break even.

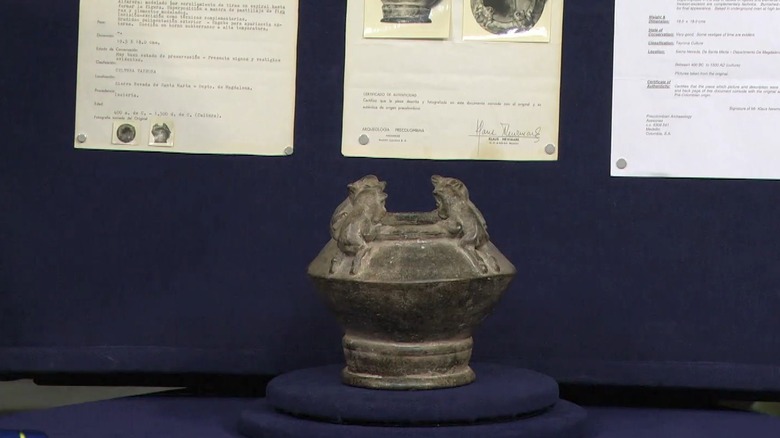

Pre-Columbian bowl

John Buxton seems to have encountered quite a few fakes in his time on the American version of "Antiques Roadshow." Maybe it's because he's so often on deck for tribal and ancient art, which may not always have clear documentation or other forms of provenance. On a 2016 episode, he spoke with a guest who hoped that the small vessel on the table between them was from the pre-Columbian history of the Tairona people. The guest even brought along documents purporting to authenticate the ceramic bowl, which included four finely made animal figures on the rim and a human one in the vessel itself.

Yet, while Buxton was complimentary toward the artistry of the bowl, he wasn't so keen on its historic pedigree. The figures were more than a bit odd for the established artistic tradition of the Tairona, for one. Then, tapping on the vessel, Buxton noted the high pitch of the noise. That would be difficult to achieve if the piece had been fired authentically in a low-temperature, old-school pit kiln. The condition of the clay instead hinted that it had been fired in a far more modern electric kiln, which reaches much higher temperatures. With an appraised value of just $300 at most, the poor guest was out a hefty chunk of money from his original $1,800 purchase.

Inscribed silver box

The May 2021 episode of the BBC's "Antiques Roadshow" at Stonor Park included an intriguing silver box that initially must have drawn the attention of many watchers. Though it was small and relatively plain, it contained an inscription that read: "The gift of Stella to Dean Swift" (via The Sun). As appraiser Marc Allum clarified, the Swift in question was 18th-century writer Jonathan Swift, author of "Gulliver's Travels" in 1726. It turns out that Swift was close friends with Esther Johnson, the daughter of a housekeeper who later came to be called Stella and who was purported to be Swift's muse and perhaps even his secret wife.

That makes for an interesting backstory that could boost the value of the box. If only it were genuine. As Allum pointed out, the box was made out of a material known as Sheffield Plate. That's a key fact, as Sheffield Plate first hit the scene in 1743. Meanwhile, Stella had died in 1728, making the inscription a clear fake. Moreover, a closer inspection revealed that the inscription was stamped, not engraved. The guest took the news that it was only worth about £40 at most with equanimity, saying she was glad for the opportunity to learn more about Stella and Jonathan Swift.

Buffalo robe

The guest who brought what appeared to be a buffalo robe to "Antiques Roadshow" said that she had purchased it from a handyman who had offered to sell her the piece after helping redecorate her mountain home. It had reportedly been sitting in storage for three decades, though its provenance was never confirmed. Appraiser John Buxton said that the art form of the painted buffalo skin was an important part of Plains Indian culture. Different tribes in the region have used preserved buffalo skins as canvases to make decorative pieces and also create records of important events like battles and spiritual visions. Outsider interest in buffalo robes peaked in the 19th century, though they remain of interest to collectors today.

However, Buxton started to note several issues with the piece in front of him. It had what first looked to be an authentic design, including a series of holes on the edge that would have been made by stakes people set to stretch the skin during the tanning process.

However, the repairs he spotted on the robe were stitched with cotton thread that looked to have been aged, not authentic sinew sourced from the buffalo itself. The hide also appeared to have been tanned using more modern techniques instead of traditional brain tanning. As a decorative piece, it was appraised as $1,000 to $2,000, so at least the guest was able to easily make back her initial $300 investment.

Kota guardian figure

On the BBC version of "Antiques Roadshow," appraiser Ronnie Archer-Morgan was surely intrigued by what first appeared to be a guardian figure made by a Kota craftsperson from Gabon. "They're such iconic examples of African tribal art," he told the guest who brought the piece before him. "They've influenced the greatest modern artists of all time. ... They are very, very sought after" (via Express). Known as mbulu ngulu, the figures were originally crafted to embody the power and spirit of the ancestors and were originally found in association with family remains stored in baskets or bark containers beneath the figure.

With such a glowing start, it hurts to hear Archer-Morgan break the bad news. Though he admitted that the art piece between them was very nice, it wasn't quite the correct size. According to Archer-Morgan, it was likely made in 1980 — a far cry from authentic pieces where some of the finest examples tend to come from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, it wasn't all doom and gloom. Archer-Morgan gave the figure a value of £150, which represented a pretty good deal considering the guest originally paid just £1.50 for the figure. And, given the fraught history of artwork and objects that have been taken from African people without permission, it may be just as well that this wasn't genuine after all.

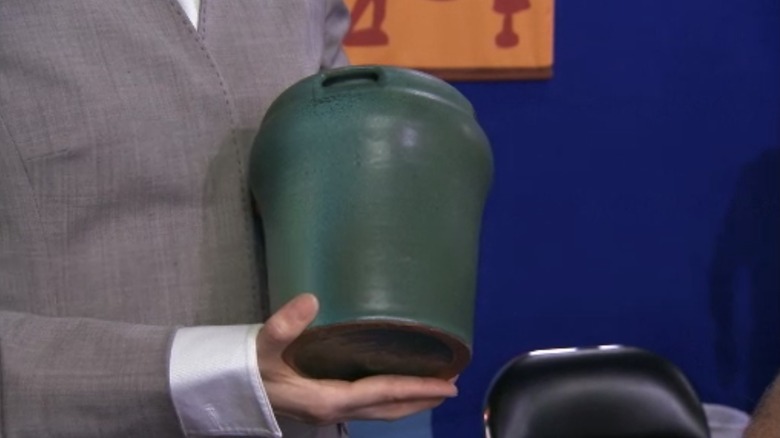

Teco vase

To someone not in the know, the vase that appeared on a 2011 episode of American "Antiques Roadshow" may not have seemed like much. But the clean lines and dark green glaze of the piece indicated — to the guest, anyway — that it might be a valuable TECO vase. The Teco Pottery company (the name comes from a mashup of terra cotta, a type of ceramic) started producing decorative pieces in about 1902 and continued to do so until 1929. The wares produced by TECO became especially known for matte glazes in green hues, sometimes applied to pieces that towered more than 7 feet.

But was the much smaller vase on "Antiques Roadshow" the real deal? According to appraiser Suzanne Perrault, it was no such thing. "It's a beautiful pot, and it has nice arts and crafts lines," she told the seemingly anxious guest before her (via PBS). Yet the glaze wasn't the right shade of TECO green. She also noted that it was a bit too heavy and sported red clay and ridges that weren't characteristic of genuine TECO pieces. She noted that real TECO vessels were typically cast and not thrown on a pottery wheel, a more hands-on technique that may explain the unusual ridges. Perrault estimated it was made in the previous two decades and was worth, at most, $200. "Somebody spiked that sale, which is a shame," she concluded.

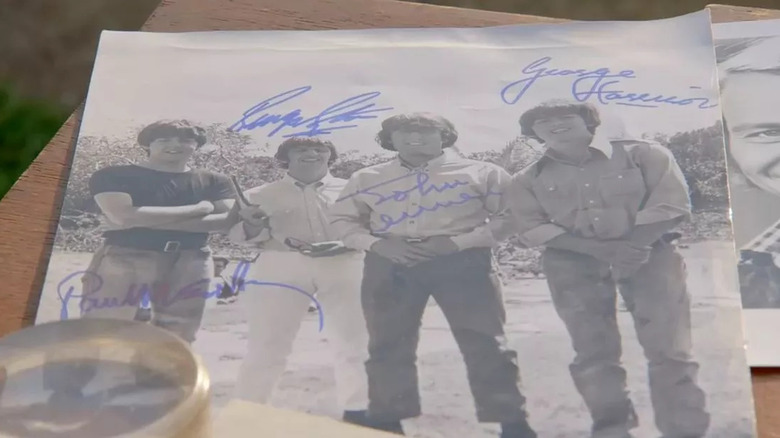

Signed Beatles picture

Beatlemania continues to this very day, or so two sisters had probably hoped when they appeared with their collection of Beatles photos and papers on a 2021 episode of the British "Antiques Roadshow." Yet, one signed picture of the Fab Four proved troublesome. Expert John Foster told the siblings that the signatures were obvious fakes. The tell? An odd stiffness to the signatures, which wouldn't make sense for young superstars who had almost certainly signed their names countless times at that point in their careers. The signatures were more likely made by one of the band's employees, who were known to sign photos and other memorabilia in an attempt to ease the overwhelming demand set by fans of The Beatles. Compared to more fluid signatures that were confirmed to come from the band members, said Foster, the difference between those and the fake was all the more obvious.

Thankfully for the women, the fake signatures weren't the only thing they were bringing to Foster's attention. Their father, a stuntman, had left them an impressive cache of photos, papers, and other Beatles ephemera that still held some welcome surprises. One, the back of a call sheet from the 1965 film "Help!," contained what appeared to be genuine signatures of all four band members. With this discovery, Foster appraised the whole collection at a very respectable £5,000.

Islamic glass cup

If appraiser Andy McConnell had been holding a real Islamic glass cup with more than a millennium of history to its name, it would have been one of the most exciting finds in the history of "Antiques Roadshow." Islamic glassmakers rightfully earned high praise for their work creating finely wrought, colorful glass pieces beginning around the 7th century in Egypt and nearby parts of Asia.

With its carved text and figures, the vessel certainly looked worn enough to live up to 1,000 years of history. It also seemed to bear the marks of having been in contact with dirt for some time. Alas, McConnell said that the engraved marks were made with acid. If the shape of a fish and Arabic text had really been ground into the glass centuries ago, artisans would have left behind tool marks. The use of acid is part of more modern glassmaking techniques.

McConnell generously gave the piece a value of £800 (the price the guest actually paid for it), saying that he put great stock in the guest and the value that the man had assigned to the piece — and perhaps mitigating some of his obvious disappointment at having to tell the guest (in front of a crowd, no less) that it was far from genuine. He also left the door open for mistakes, saying the man should consult with experts at the British Museum just in case. "And If I'm wrong," McConnell said, "come back and kick me, please" (via BBC).

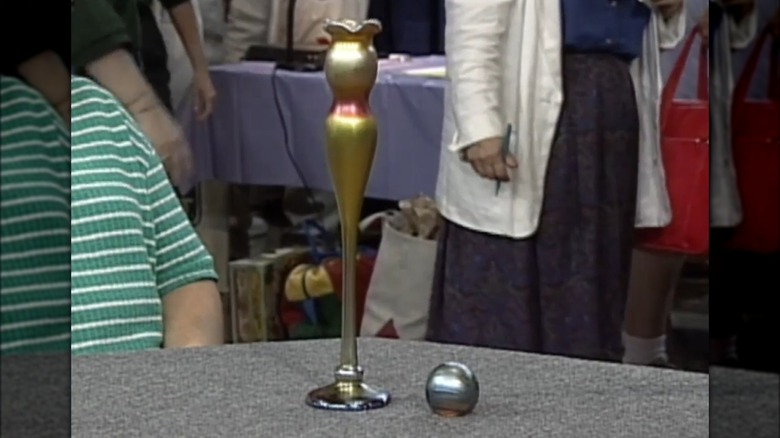

Tiffany vase and paperweight

You don't have to be a professional antiques appraiser to know that Tiffany glass is big business. American designer Louis Comfort Tiffany made his artistic reputation on intricate glassworks, establishing a studio full of fellow creatives that made Tiffany a stalwart name in the world of design. Ultimately, Tiffany established a myriad of businesses that produced a variety of glass-based decorative pieces and artworks. Many of these incorporated iridescent glass that shimmered with a rainbow of colors and was based on ancient examples unearthed from Roman and Syrian sites. Tiffany and his associates eventually called their take on this ancient effect Favrile glass.

So, when a guest brought just such an opalescent glass vase and paperweight to a filming of an episode of "Antiques Roadshow" in Richmond, Virginia, it wasn't unreasonable to think that she had something truly special. But appraiser Barbara Deisroth quickly moved to deflate any untoward hopes. "I realized what they were trying to be," she began. "They're trying to be glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany made at the turn of the century. In fact, they're not" (via PBS). Though the pieces were signed, the signatures appeared to be fake, while the pieces were deemed too clunky by Deisroth to be genuine. She deemed the paperweight — which Tiffany never made, at least not in the style seen on the show — to be worth $30. The vase was, at most, just $200 in value.

Sévres box and Ludwigsburg urn

By the 19th century, the French Sévres porcelain factory had established itself as a major manufacturer of trendy porcelain pieces that landed in well-heeled homes across the continent. Thanks to smart management, awareness of changing tastes, and a willingness to take on new and improved production techniques, Sévres was able to hold onto its position for many decades and remains a porcelain manufacturer to this day. But modern collectors are especially interested in antique examples from this company, like its elaborate and finely painted service sets. No surprise so many factories applied fake Sévres marks to inferior pieces.

Perhaps the guest who presented a supposed Sévres box wished they knew about all this before they went on a Season 7 episode of "Antiques Roadshow" filmed in Kansas City. The guest also brought along an urn that was purportedly made at the Ludwigsburg porcelain factory, another producer of fine pottery based in Germany dating to 1758. Yet, when appraiser David Lackey took a look at both pieces, he found some serious issues. Though both pieces were pictured and described in an auction catalog and, in Lackey's opinion, were very finely painted, they weren't genuine. The manufacturer's marks were the main tell, as they just weren't right (as is the case for many supposed examples of pottery from either manufacturer, said Lackey). Even with the fake marks, the guest was told that he could get anywhere from $2,500 to $3,750 for the set.

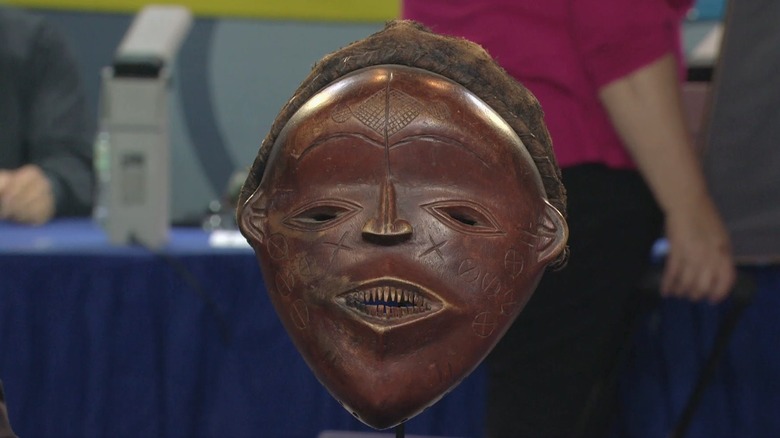

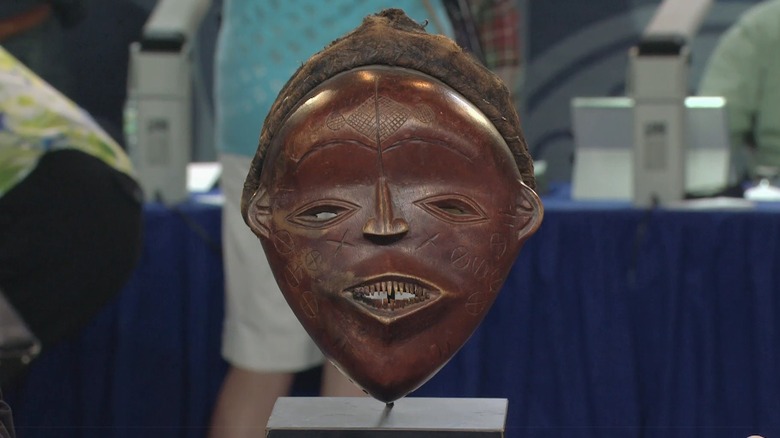

Chokwe mask

The guest who presented a presumed Chokwe dance mask on a 2018 episode of the PBS version of "Antiques Roadshow" came into possession of the piece after a series of trades back and forth amongst aficionados of African art. The Chokwe people, who hail from what is now southern Congo, northeastern Angola, and northwestern Zambia, are well known and respected for their mastery of many different art forms, including wooden mask carving. Traditionally, masks used in rituals and dances are made with distinct forms that often include markings engraved on the mask's cheeks and forehead and fiber elements such as raffia.

But, back on "Antiques Roadshow," appraiser John Buxton found some serious issues. Sure, the mask initially looked like it belonged to the Chokwe tradition, but when Buxton turned it around, he found that the holes where raffia might have been affixed were oddly free of wear. Strange indeed for a mask that should have been used during an energetic dance. Furthermore, the interior of the mask didn't have the marks one would expect of a mask that came into contact with a sweating human face. Buxton ultimately concluded that it was an intentional fake, making it worth just $200 to $300. Compared to the six figures that a real Chokwe mask could get on the art market, it was likely a genuine disappointment to the guest.

Two Chinese vases

Pottery from ancient China can easily become the centerpiece of someone's collection, at least if jokes about shattering priceless Ming vases are at all reflective of reality. But the vases presented on a 2001 episode of "Antiques Roadshow" filmed in Miami didn't appear to be from the Ming dynasty. Instead, appraiser James Callahan said that at least one of the vases had the look of a Tang dynasty vessel. Spanning A.D. 618 to A.D. 907 the Tang dynasty saw ceramic artists innovate the use of glazes, bringing new colors to China's pottery.

Over on "Antiques Roadshow," however, the vessels were pretty suspect. Callahan took a small tool and gently scraped the top of one piece, leaving behind a mark. If the vase in question were made of hard jade, that scratch would never have been made, meaning the vessel was likely made out of a softer soapstone or similar rock. The piece also included components made from aluminum, a material that wasn't identified and put into common usage until well into the 19th century.

The other, smaller vase was at least made out of ceramic, though the Tang-style metal piece that had been applied to it was not gold, but a cheaper anodized metal — which prompted the guest to admit that she had noticed it rusting. Though she didn't specify how much she and her husband had paid for the pieces, hopefully, it wasn't much. Callahan gave them a value of just $10 to $20 each.

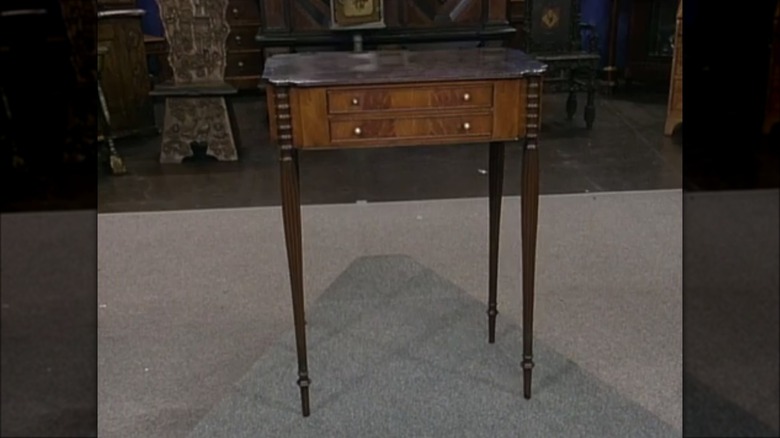

Federal sewing table

First made during the late 18th century, Federal furniture is linked to both the neoclassical revival of ancient design and the emergence of the American republic, which in some quarters called for a design shift away from Baroque excess (though the clean forms of Federal-style furniture were already popular in Europe by the American Revolution). With its straight lines, symmetrical design, light appearance, and innovative use of different wood types, Federal furniture remains highly popular amongst modern antique collectors.

Yet, that level of popularity can push less scrupulous makers to create fakes. That was the unfortunate discovery of one guest on a 2012 episode of the American "Antiques Roadshow." As the guest told it, his grandfather had come across the piece while lost on a road trip in New Hampshire. Happening upon an antique shop, he found what appeared to be a small Federal sewing table.

Appraiser Leigh Keno agreed that it was a Federal-style piece but proceeded to point out the telltale signs of a fake. A drawer, which should have had dark, oxidized wood, actually sported pieces that had been stained to look aged. And parts that should have oxidized gradually or not at all were simply stained all over. "And that's something that was done in the teens and '20s by a whole group of fakers in Boston that knew that this was a fashionable style ... so they were knocking them out in large numbers," Keno told the guest (via PBS).

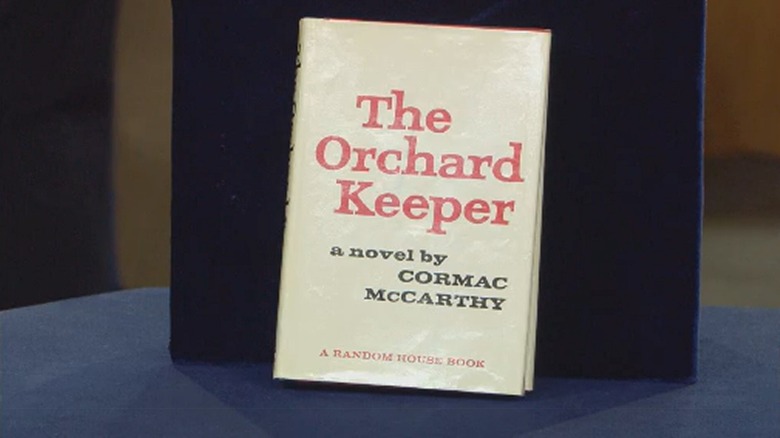

Cormac McCarthy dust jacket

While other antique markets might see ups and downs, the rare books trade has been surprisingly resilient, staying strong even in the face of massive upheavals like the COVID-19 pandemic. So, perhaps it comes as no surprise that appraisers occasionally come across fakes. However, given the many details that experts can consider, from the quality of the paper to the authenticity of the binding, it may be easier to spot those fakes compared to other objects.

Such was the case with what appeared to be a 1965 first edition of Cormac McCarthy's "The Orchard Keeper," which appeared on a 2010 episode of "Antiques Roadshow." To be fair, appraiser Ken Gloss did confirm that the book itself was a genuine article. The dust jacket, however, was a different story. Gloss explained that this was a serious issue, as dust jackets comprise almost the entirety of a rare book's value. Because of this, some fakers are motivated to put on a facsimile dust jacket. Other people may inadvertently mislead others simply because they wanted a nicer, less-worn dust jacket to wrap around their book.

Gloss noted that the green fabric around the book didn't properly bleed through to the jacket, which it likely would have if the book and dust jacket had been together from the start. That meant the value plummeted from what could have been an estimated $3,500 to just $100. The guest remained even-keeled, however, explaining that they had gotten the book for free.