The Tragic History Of Cancer In The British Royal Family

For centuries, members of the British royal family have lived lives of luxury, with the best of everything, from food to housing to medical care. But there are some great equalizers in life, and no matter how privileged they may be in every other way, the royals still face the same risk of cancer as their subjects do.

Over the past century in particular, but further back in history also, the British royals have received many official and publicized cancer diagnoses. And at other times, while no official diagnosis was made, historians and medical professionals have a pretty good idea, based on recorded symptoms, that the individual had cancer. Like the rest of the population, the results of their bouts with cancer varied, with a few receiving treatment and surviving, others dying from the disease, and, in the case of living royals, some fights that continue in the present day.

From the Tudor period to the 21st century, this is the tragic history of cancer in the British royal family.

Mary I

Queen Mary I was Henry VIII's child by Catherine of Aragon, the first of his six wives. After her half-brother Edward VI died childless at just 15 years old (and after a nine-day to-do with Lady Jane Grey), Mary came to the throne in 1553, and soon married her cousin Prince Philip of Spain. Within months of her marriage, she announced she was pregnant. Considering she was 37 and her husband wasn't into her, people at court were shocked, but it did look like she was carrying a baby, since her stomach was enlarged, and she claimed to have felt the fetus move.

It slowly became clear, however, that Mary was not pregnant, although the queen continued to insist that she was until 11 months into her "pregnancy." The same situation played out a few years later, this time with Mary holding out hope that she would imminently give birth for over a year.

Several things can cause phantom pregnancies, including hypothyroidism and pseudocyesis – the latter being a mental health issue where a person who is fixated on having a child convinces themselves they are pregnant — but one common theory of historians is that Mary was suffering from stomach, ovarian, or uterine cancer. This would explain the swelling belly and stomach pains she also experienced. While it is possible she died from the flu, it's considered more likely it was cancer that killed her in 1558, aged 42.

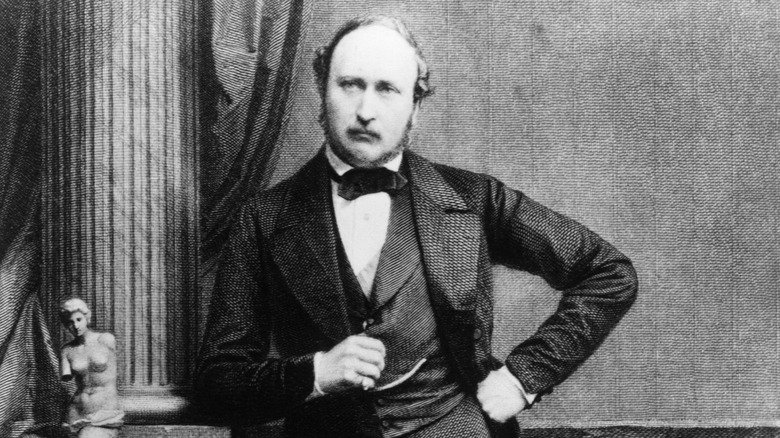

Albert, Prince Consort

Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, died in 1861, aged just 42. Albert certainly didn't help himself: he kept a punishing schedule that exhausted him and aggravated his generally weak health. For decades, historians believed Albert died from typhoid – a disease caused by inadequate sewage removal, causing food and water to be contaminated by fecal matter. Even royals were at risk of this endemic disease at the time.

However, the more recent consensus is that Albert probably had stomach cancer, and that is what killed him. For several years before his death, Albert had suffered from extreme stomach problems. Victoria described his symptoms as being violently painful spasms and cramps, and he admitted he would sometimes not eat in the hopes he wouldn't have stomach troubles for a bit. These were not minor incidents, either. They could last weeks at a time, often leaving him bedridden.

On top of the agonizing pain he experienced, he had other symptoms that point historians in that direction, including swollen gums. Perhaps the biggest predictor of him having the disease is that it ran in his family: His mother had been just 30 years old when she died of stomach cancer. Victoria refused to let the doctors perform an autopsy on Albert, so there is no way of knowing for sure if he had cancer, and there are still historians who lean towards the typhoid theory, although the evidence for cancer is quite convincing.

Victoria, Princess Royal

The eldest child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert was Princess Victoria (called Vicky in the family). She was given the title Princess Royal. and once she married, she became the crown princess of Prussia and subsequently the empress of Germany — for a mere 99 days.

The reason Vicky held the latter title for so short a period was that by the time her father-in-law died, aged 91, her husband Frederick was dying of throat cancer. In fact, when he ascended to the throne, his case was so advanced that he was unable to speak. While Frederick originally planned to have surgery on his larynx, a second opinion from an English doctor changed his mind. He died in 1888, aged 56.

Exactly a decade later, Vicky was out riding when she was thrown from her horse. While she was unharmed, the doctor who looked her over after the riding accident discovered what he believed was breast cancer. This diagnosis was later confirmed, and it was determined to be inoperable. At first, she kept it a secret from all but her mother and two of her siblings. Finally, she was forced to tell some of her children but swore them to secrecy. She didn't even tell one of her daughters because she didn't trust her to be discrete. By 1899, she was clearly unwell. The cancer had spread, and Vicky was bedridden and in pain regularly. Despite a brief remission of her symptoms, she died in 1901.

Edward VII

King Edward VII (pictured center) was the eldest son of Queen Victoria and reigned from 1901 to 1910. He was a notorious hedonist and playboy, but perhaps he should be better known for helping advance the use of radium in cancer treatment.

In 1907, Edward was vacationing in what is now Czechia, and reporters noticed that every two days, he went to a certain hotel for about an hour. While many minds jumped to salacious possibilities, in reality, he was receiving a form of electrical treatment on a basal cell carcinoma — or "rodent ulcer" — on the side of his nose. During this skin cancer treatment something went wrong, and his majesty received an undignified electrical shock. Following that, his doctor was forced to find a different kind of treatment and turned to a relatively new radium therapy that was being used in France. However, Edward was so impatient that to keep the radium against his skin, it had to be applied to a special pair of glasses he could wear while he read the newspaper.

The technique worked, and Edward was so happy with the results that he encouraged the founding of the Radium Institute in London. The year after his successful treatment, he wrote in a letter, "My greatest ambition is to not quit this world until a real cure for cancer has been found, and I feel convinced that radium will be the means of doing so!" (via "King Edward VII: A Biography" by Sir Sidney Lee).

George VI

When King Charles III's cancer diagnosis was announced in 2024, historian Sarah Gristwood told NBC News that this was a significant break from the royal family's tradition of keeping medical issues extremely private. She explained, "When Charles' grandfather, George VI, was very gravely ill, the severity of his condition was kept not only from the public but from the patient himself. Those were the attitudes of the time."

It seems ridiculous today, but it's true. George VI was a heavy smoker, and in 1949, after years of health problems, a section of his right lung was removed. Two years later, further symptoms resulted in doctors finding a cancerous growth in his left lung. This time, the entire lung was removed. While you might think that it would be important for a doctor to tell a patient why they were having one of their vital organs removed from their body, the cancer diagnosis was kept from the monarch, and instead, he was given the vague explanation of "structural abnormalities." The king and queen didn't talk about his medical problems, although the doctors did give her the bad news that he probably only had a year to live, and she was aware he had cancer.

George died in his sleep on February 6, 1952, and, because he also had heart problems, his cause of death was recorded as coronary thrombosis. However, medical historians have recently put forward the theory his death was caused by the cancer spreading to his remaining lung.

Edward VIII

Edward VIII gave up the throne not long after he ascended to it, abdicating in 1936. From then on, he was known as the Duke of Windsor, and he happened to be a very heavy smoker. By the time his throat cancer was discovered in 1971, it was inoperable. His wife, the controversial American divorcee Wallis Simpson, later said, "I told him to stop smoking all those cigarettes. ... He was always nervous about making speeches and that's why he smoked so much. He did cut down. ... But I guess it was still too much; it all added up" (via "The Duchess of Windsor: The Uncommon Life of Wallis Simpson" by Greg King). The following year, more cancer was discovered, and it was clearly terminal.

The treatments and symptoms left the duke weak and bedridden. As the end came, he was unable to leave his home in Paris. While he had effectively been banished from the royal family after his abdication, 10 days before he died, his niece Queen Elizabeth II came to visit him. He did not have the strength to come downstairs, but he insisted on getting out of his bed and sitting in a chair when she came up to his room.

The Duchess of Windsor had her own cancer scare years before. In 1944, she underwent an appendectomy, and during the surgery, doctors found tumors in her stomach. These turned out to be cancerous, but after they were removed, she did not have any recurrence of the disease.

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon was the wife and queen consort of George VI. After his death in 1952, she was known as the Queen Mother, to differentiate her from her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II. By the time of her own diagnosis, the Queen Mother had already seen the devastating toll cancer could take on a person, since her husband had suffered from lung cancer for several years before he died.

On December 6, 1966, the Queen Mother attended two events before going to the hospital. There, the 66-year-old would undergo a scheduled operation for colon cancer. While she was aware of her condition — unlike her husband, who was never told by his doctors he had cancer — the public was kept just as much in the dark about her diagnosis as they had been about the late king's. However, it was impossible to hide the fact that she was in the hospital for several weeks and that she had subsequently canceled months of planned events. The lack of information left a vacuum for rumors to fill, and for decades many believed she had a colostomy. It was not until an official biography of the Queen Mother was released after her death that the cancer diagnosis became public. Fortunately, the cancer did not return.

It would not be her last cancer diagnosis, though. In 1984, she had another secret procedure, this time to remove a cancerous lump in her breast. This operation was also successful, and the Queen Mother lived to be 101.

Elizabeth II

It was not unexpected when Queen Elizabeth II died on September 8, 2022. She was, after all, 96 years old and had been in poor health for a while. In 2021, she'd spent a night in the hospital, and it was becoming common for her to cancel scheduled events at the last minute due to medical issues, especially problems with mobility. In one of the last photos of the monarch (above), she had dark bruising on her hands, and all these things combined meant it was no surprise that her official cause of death was listed as "old age."

However, in a book on the late monarch that was serialized in the U.K. tabloid The Daily Mail, a British media personality and close friend of the late Prince Philip named Gyles Brandreth dropped a bombshell: "I had heard that the Queen had a form of myeloma — bone marrow cancer — which would explain her tiredness and weight loss and those 'mobility issues' we were often told about during the last year or so of her life."

Of course, no matter how well-connected to the royal family Brandreth was, even he frames this alleged diagnosis as something he "heard." The palace did not respond to the claim with either a confirmation or denial, although some royal watchers theorized that Brandreth must have had unofficial approval from the royal family to include this bit of information in the book.

The Duchess of York

On New Year's Eve 2023, Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York (commonly known as Fergie), announced that she had been successfully treated for breast cancer in an Instagram post. She noted that she now had "Derek on my left."

On her podcast Tea Talks (via Town and Country), Fergie explained that this was the name she had given her reconstructed left breast after undergoing a mastectomy. She said, "I'm just coming to terms with my new best friend Derek on my left, he's called Derek. And he's very important because he saved my life." Why, exactly, did she name her new breast Derek? "I don't know it just made me laugh that I have a friend who's with me all the time who's protecting me with his shield of armor." Fergie was clearly enjoying finding humor in such a difficult situation, and listeners also learned that Derek's neighbor "Eric" was jealous of how good Derek looked.

Tragically, the duchess was soon hit with a second cancer diagnosis. Her office released a statement in January 2024 (via People): "Following her diagnosis with an early form of breast cancer this summer, Sarah, Duchess of York has now been diagnosed with malignant melanoma." In fact, the mole was noticed and biopsied by the doctor doing her breast reconstruction surgery. Friends told the outlet that the double whammy was a huge blow. However, she remained upbeat, at least publically, waving to photographers as she left the hospital after one of her skin cancer treatments.

Charles III

In January 2024, King Charles III was admitted to the hospital for an operation on an enlarged prostate. In order to assure the public this was nothing to be concerned about, the palace made sure to note it was a very common scheduled procedure, and used the opportunity to remind men to talk to their doctors about their own prostate health. The surgery was evidently successful, with Charles soon returning home. A little more than a week after his operation, he was photographed walking to church and greeting some of his subjects.

However, the day after this public appearance, the world learned that the British monarch had cancer. While the palace did not say what kind it was, reports indicated it was not prostate cancer, but whatever type it was, it was discovered during his prostate treatment. The palace released a statement (via NBC News) explaining, "During The King's recent hospital procedure for benign prostate enlargement, a separate issue of concern was noted. Subsequent diagnostic tests have identified a form of cancer." It went on to say that the king would be receiving treatment, although no details on what kind were included, only that it meant he would not be fulfilling any public duties for a while. Additional information came from Prime Minster Rishi Sunak, who stated that the cancer had been caught early.

Prince Harry immediately returned to the U.K. from California when his father's diagnosis was announced, although Meghan Markle stayed behind with the children.

Catherine, Princess of Wales

In early 2024, Catherine, Princess of Wales (still commonly called Kate Middleton by the public), did a disappearing act. She wasn't seen for months, and although Kensington Palace announced she had undergone surgery, the lack of details, combined with a disastrous Photoshopped family portrait scandal, saw rumors swirl that something serious was up. The internet managed to work itself into a frenzy, with theories ranging from she had died to that she'd undergone a Brazilian Butt Lift.

The reality was tragic. On Friday, March 22, Kate released a short video where she explained what she had been going through. She said, in part, "In January, I underwent major abdominal surgery in London and at the time, it was thought that my condition was non-cancerous. The surgery was successful. However, tests after the operation found cancer had been present. My medical team therefore advised that I should undergo a course of preventative chemotherapy and I am now in the early stages of that treatment" (via People).

The explanation for her delay in telling the public the truth was finding a way to deliver this news to her children and help them process it before everyone else found out, which was understandable. Once the public knew what was happening, many apologized for the rumors they had spread about Kate's health and condolences poured in from around the world. Her diagnosis also meant that three members of the royal family were undergoing cancer treatment at the same time, which was unprecedented.

Katherine of Aragon

Henry VIII married Katherine of Aragon, the widow of his brother Arthur, shortly after he became king in 1509. While they were happy together for many years, their lack of a son who lived past infancy – and the appearance of Anne Boleyn at the English court — eventually resulted in Henry going to great lengths to rid himself of his queen. Unlike some of his later wives, Katherine would keep her head. However, the king did everything else he could to make her life miserable after ending their marriage.

Katherine was effectively banished from court and made to live in increasingly uncomfortable castles. Most of her furniture was taken away. She was not allowed to see her only living child, the future Mary I, and her friends had to ask permission from Henry to visit her. However, the king's subjects still supported her, which annoyed him greatly.

Henry was kept well informed of Katherine's increasingly bad health. He believed she might have dropsy, and expected her to die any day, something which those close to the king knew would make him extremely happy. Katherine was 50 years old when she died on January 7, 1536. When her body was cut open in preparation for burial, it was discovered that her heart had a black growth on it. While at the time many of those who learned about this thought it proved Henry had poisoned Katherine, in reality, it was most likely melanotic sarcoma, aka cancer of the heart.

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were not even married yet when they decided that their future second son would eventually become ruler of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, in what is now Germany. But when that son, Prince Alfred, showed up in 1844, he had many decades to fill before he'd actually get the job. So he joined the Royal Navy and traveled as far away as Australia, was given the title Duke of Edinburgh, was made a Knight of the Garter, got married to a daughter of the Russian tsar, and had a handful of children. Finally, in 1893, his uncle died, and Alfred became Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

However, he would not have very long in that role. Alfred was said to have aged rapidly and been in ill health for some time, which probably had something to do with how much alcohol he drank.

In 1900, Alfred traveled to Vienna to see several specialists. They discovered a cancerous growth on his tongue, although Alfred was not actually told how bad his diagnosis was. He went to Schloss Rosenau, one of the ducal homes, to convalesce, thinking he would be better in no time. According to contemporary Associated Press reports (via the Los Angeles Times), his condition deteriorated rapidly, with the throat cancer almost suffocating him, resulting in the need for a tracheotomy. He died on July 30, 1900, aged 55. To the wider world, his death was completely unexpected, with newspaper headlines reflecting the public's shock.

Caroline of Brunswick

In 1821, Caroline of Brunswick arrived at Westminster Abbey dressed in formal robes, ready to be crowned Queen of England. Her long-lived father-in-law, George III, had finally died the year before, and her husband of 25 years was now George IV. There was just one problem with her plan — the king hated her, and she had been told in no uncertain terms not to come to the coronation. In fact, the government had tried to bribe her with a very large amount of money to not even be in England at the time.

But Caroline was technically queen, and she wanted to be treated with the respect that position demanded. She pounded on the doors of the Abbey, ordering the pages to let her in, but she didn't get her way. Eventually, she gave up and returned home. The stress of the event had clearly taken its toll on her, as one day later, she collapsed, and within three weeks, she was dead. The uncrowned queen was 53.

Considering what an embarrassment she was to George, many people thought he had poisoned her. However, it's generally accepted by modern historians that she had stomach cancer, although it's possible her death might ultimately been the result of something like a ruptured bowel. Unlike George, the people of England loved Caroline, and during her funeral procession in London, they rioted, resulting in two deaths.

Anne Hyde

Anne Hyde was the mother of two queens of England, although she did not live long enough to hold that position herself. When the commoner Hyde controversially married the future James II, he was only the Duke of York, and his older brother had just become Charles II during the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Hyde gave birth to two daughters who survived, the future queens Mary II and Anne. But perhaps her biggest influence on British history was converting to Catholicism, and encouraging her husband to do so as well, which would result in him losing his throne decades later to one of their daughters.

Despite the fact that James had caused a huge uproar and angered his family by marrying someone so far below him in social status, he still cheated on his hard-won wife. While she also had at least one affair, her husband's infidelity hurt Hyde deeply, and she found solace in food and jewelry.

While Hyde's health had been in noticeable decline, no one realized how serious it was, and her death from breast cancer in 1671 at age 34 came suddenly and unexpectedly, only weeks after she gave birth for the final time. After Hyde's death, the courtier Margaret Blagge wrote in her diary: "None remembered her after one week, none sorry for her. She smelt extremely, was tossed and flung about, and everyone did what they could with that stately carcass" (via "The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough" by Ophelia Field).

Mary of Modena

Anne Hyde died before her husband James became king of England, but his second wife, Mary of Modena, would get the title of queen consort — before losing it when James II was overthrown in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The couple and their children fled to the Continent and spent their remaining years trying to regain the throne for either James or their son.

Once she became a widow, Mary spent a lot of time in a French nunnery; in fact, she'd wanted to become a nun when she was a kid, before James decided he was going to marry her. The religious life suited her so well that some in France even brought up the possibility of sainthood for the ex-queen of England. While that never happened, she was buried at the convent.

Besides their shared husband, Anne Hyde and Mary of Modena had another thing in common: they both died of breast cancer. Mary knew she had been ailing for years, possibly as early as 1705. In 1715, she traveled to Bar-le-Duc, ostensibly to see her son, but most likely because the area had a long reputation for curing cancer, both by drinking the water there and seeing some of the resident medical specialists. The trip was not successful, however, and she died of breast cancer in 1718, aged 59. Neither her son nor her husband were ever returned to the English throne.

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

There are multiple Mary Tudors, which can be confusing. This one is not Mary I, but her aunt, the youngest sister of Henry VIII. For political reasons, Henry married her off when she was still a teenager to the 52-year-old king of France, who then promptly died. When Charles Brandon, the man Mary had secretly been in love with all along, was sent to France to escort the widow back to England, the pair eloped. Henry was furious, but eventually forgave them once they agreed to pay him a huge sum of money.

Her position made Mary an important person in the English court, but she attended fewer and fewer events, even as her husband stayed by his good friend Henry's side constantly. In 1528, she came down with a common disease of the time known as the sweating sickness, and apparently never fully regained her health after that. She was especially bothered by an intense pain in her side. She would write to her brother the king, asking permission to see his personal doctor because she was desperate for a cure. Her husband Charles also wrote to Henry, saying she was in so much pain she couldn't do anything but sit and cry.

Whatever was causing this unbearable pain — while historians believe it was probably cancer, it's also possible it was a symptom of tuberculosis — finally killed the long-suffering Mary in 1533. She was only 37.

Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves was by far the luckiest of all of Henry VIII's wives. While he went through with the marriage to his fourth wife in 1540, he then immediately tried to figure out how to get out of it. Only months after their marriage, Anne was offered a divorce, as well as the position of the "King's Sister." He also gifted her several homes and a yearly allowance. Anne knew a good deal when she saw it, and stayed in England, single and happy, for the rest of her life. She was one of the most important women at court, was friends with both her ex-husband and his daughters, and spent her time gambling and cooking. Household records show she was also very fond of beer, perhaps to be expected since her homeland of Cleves is in what is now Germany.

Towards the end of her life, Anne dealt with a lingering health issue. Historians think the most likely explanation was cancer, although, since no autopsy was performed, it is impossible to be sure. It became clear Anne was dying, though, so she made her will and got her affairs in order. She outlived Henry by 10 years, and died aged 41 when his daughter Mary I was on the throne, in 1557. Her friendship with the queen, the woman who had been her stepdaughter for just six months, was so great that Mary ordered Anne to be buried in Westminster Abbey, a great honor that none of Henry's other wives received.