The Swans: The Real-Life Story Of Truman Capote's Elite Female Circle

It's easy to imagine that fame for the sake of fame, and drama for the sake of drama, are features of the modern media landscape. After all, this is an age in which reality TV characters and social media influencers seem to be increasingly stealing the spotlight from bona fide actors, authors, artists, and the like. But self-made celebrities who, for the most part, celebrate themselves are nothing new, nor is their tendency to tear each other down as they build themselves up.

Before the Kardashians, Real Housewives, and TikTok stars, there were people who self-promoted and/or married their way into high society. And before there was DeuxMoi, there were people who infiltrated the top tiers of the social strata and spilled the tea about it all. Particularly in America, where fortunes (and now followers) mean more than surnames, it's a story that's played out again and again, but perhaps never more scandalously than in 1975, when writer Truman Capote exposed the juicy secrets of his fabulous friends in an excerpt from a thinly veiled piece of fiction. His titillating and, for all intents and purposes, true tale tattled about everything from bad breath to cheating spouses and even murder, and involved high-profile families like the Vanderbilts and Kennedys. And the real-life fallout was even more outrageous.

Just how Capote bemused and then used his ultra-classy company has since become the topic of the nonfiction book, "Capote's Women" and the second season of the FX anthology series, "Feud: Capote vs. the Swans." The story within a story lives on because it combines everything readers, viewers, and parasocial interlopers want out of a good rag ... which Capote himself knew all too well.

Capote becomes Capote

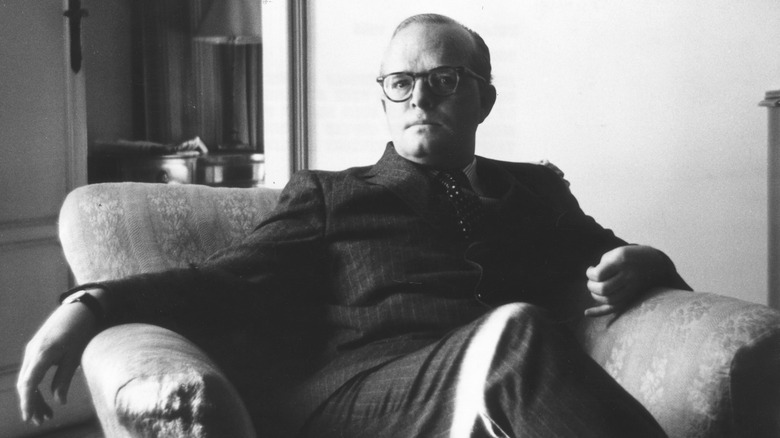

Truman Capote is remembered as the author of such literary classics as "Breakfast at Tiffany's" and "In Cold Blood," but his greatest achievement may have been how he positioned himself as the main character in a captivatingly plotted out life, against all odds.

In "Capote: A Biography," author Gerald Clarke paints a grim picture of his childhood. Born in 1924 New Orleans to already unhappily wed parents, his father, Arch, wasn't able to hold a job and often resorted to fraud to make a buck, and his mother, Lillie Mae, was flagrantly unfaithful. It wasn't long before their marriage fell apart, and a young Capote was sent off to Monroeville, Alabama, to live with relatives. He grew up anxious and lonely, with writing as his only emotional outlet.

When he briefly reunited with his mother in New York City, his way with words landed him a job at The New Yorker. But his career was as full of stops and starts (he was once fired by Robert Frost) as was his social life, and he frequently moved back and forth between the Big Apple and Alabama. His big break came with the publication of "Other Voices, Other Rooms," his highly autobiographical debut 1948 novel that dared to make a queer character its protagonist. At a time when notable personalities went to great lengths to hide their sexuality, Capote's reputation flourished as an out and outwardly effeminate man. By the time he conceived of what was to be his masterpiece, he was already deeply entrenched among Manhattan's movers and shakers.

La Côte Basque 1965 is published in Esquire Magazine

For many years, Truman Capote had been working on a masterpiece that was to be called "Answered Prayers." Capote based the title on the saying, "There are more tears shed over answered prayers than over unanswered prayers." The subjects of his novel-in-progress — the richest and most fashionable socialites of the day — certainly seemed to have had their wildest prayers answered. Like him, many of the women who'd become his companions hailed from humble beginnings and now lived lives of leisure and luxury. But, like him, rather than relying on divine intervention, they'd engineered their places in society, mostly by marrying well (multiple times if need be).

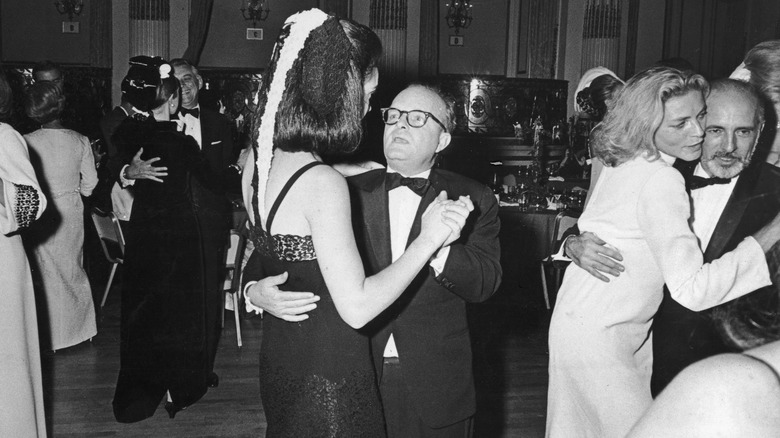

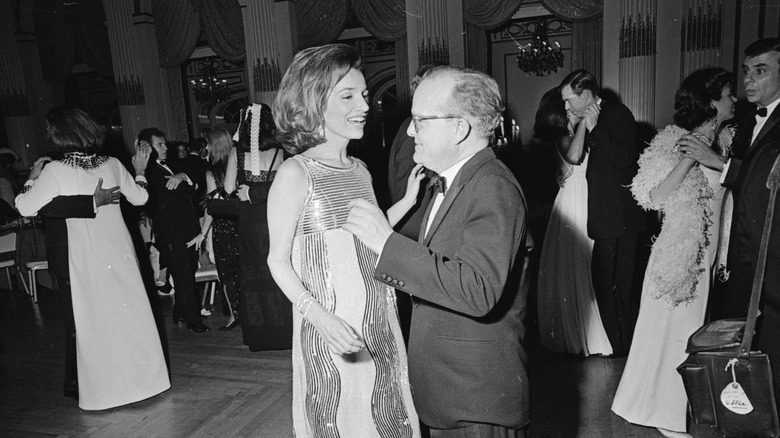

Capote first began collecting his "Swans" in the early 1950s, when his work as an aspiring screenwriter and playwright brought him into contact with studio executives and Broadway producers, as well as their wives. He became fast friends with these affluent women. He enjoyed their company, complimented them, entertained them, advised them, and earned their trust. He had the idea for "Answered Prayers" not long after, but by 1975, had missed years' worth of deadlines. In part, he was putting too much pressure on himself to make the book a towering work of genius, but mostly, he was partying more than he was writing.

As proof of progress, portions of the manuscript, including one that read like a short story, titled "La Côte Basque 1965," were published in Esquire Magazine. On those pages were the secret shames of Capote's Swans, some of whose names he hadn't even bothered to change. The author had arrogantly assumed his friends wouldn't recognize themselves. He was wrong.

Slim Keith becomes Lady Ina Coolbirth

"La Côte Basque 1965" imagines a fictional writer named P.B. Jones, clearly based on Capote himself, having lunch at a real upscale restaurant with Lady Ina Coolbirth, a fictional female friend. Coolbirth, having been stood up by her original lunch date (a Duchess), drinks too much champagne and gets loose-lipped about her coterie's deepest, darkest secrets. Thus, "La Côte Basque 1965" becomes a series of stories within a story, each delving into the personal life of one of Capote's Swans. While most of the women featured in those stories were displeased, to say the least, with their inclusion and portrayals, the inspiration for Lady Ina Coolbirth was just as displeased at being made the mouthpiece of the gossip.

Capote modeled Coolbirth on Slim Keith, a longtime friend and fellow nobody who'd turned herself into a somebody by rubbing elbows with the entertainment industry's bigwigs. She'd been thrice married, first to filmmaker Howard Hawks, then to theatre mogul Leland Hayward, and finally to British Baron Kenneth Keith. Not only had Capote's copycat version of Keith been unmistakable and unflattering, her role in the story implied she had been the one to break her cohorts' trust.

Capote had given Keith a heads-up that she was in the excerpt, but he'd led her to believe it was a bit part. In Gerald Clarke's "Capote: A Biography," she says that she adored him and couldn't believe he'd written down the contents of their conversations, nor that he'd used their friendship for personal gains in such a way.

Ann Woodward becomes Ann Hopkins

Of all the tales told in "La Côte Basque 1965," the most shocking is that of Ann Hopkins. Capote barely made an effort to conceal the identity of his friend, Ann Woodward, or the details of the criminal case for which she had become infamous. Ann was a former showgirl and aspiring actress who'd married banker, real estate developer, and horse racing aficionado William Woodward Jr.

What set Ann Woodward apart from her fellow Swans, who were often just as unhappy and unfaithful in their marriages, was the fact that she'd shot and killed her husband. She insisted his death was an accident — that she thought someone was breaking and entering and fired in self-defense — and was never tried or charged. But her side of the story was somewhat difficult to believe. Ann was rumored to have had a temper, and Bill was exiting the shower, naked, at the time. She may have gotten away with it, legally speaking, but her stature within her social circle was forever compromised, as many of her friends and acquaintances assumed her so-called mistake was really murder.

At one point, Ann Hopkins was meant to be the main character of "La Côte Basque 1965," but as the shooting (which occurred in 1955) became old news, Capote reworked the story. Even in a reduced capacity and with a changed last name, his fictionalization of Ann Woodward's life would have tragic consequences. After reading an advanced copy, she died by suicide just before its publication.

Babe Paley becomes Cleo Dillon

In real life, Truman Capote's favorite Swan was Baby Paley. Unlike some of her counterparts, Babe was born into privilege. The daughter of a groundbreaking surgeon, she first married a Harvard-educated oil magnate before divorcing him for William Paley, a businessman who would eventually run CBS.

Babe Paley was a style icon if ever there was one. She was the fashion editor at Vogue Magazine and perennially on the best-dressed list. Perhaps because Capote appreciated her style and her substance in a way that other women and heterosexual men could not, she and the author developed a unique and close bond. He was close with her husband, who went by Bill, too. Capote's access to their rarified world also meant access to the sordid details of their sex life (or lack thereof), the specifics of which he shared not only with other friends, but also in the narrative of "La Côte Basque 1965."

Capote refashioned Paley as Cleo Dillon, an extraordinary beauty and the long-suffering wife of a politically well-connected philanderer. Babe was terminally ill with lung cancer at the time, and Capote was advised to edit out the subplot, but refused. Rather than turn on her cheating husband, she directed her anger at the man she thought was her best friend. Though he may have sought to embarrass Bil, he'd humiliated her, too, and she never forgave him, never speaking to him again. Babe Paley died about three years later, in 1978, at the age of 63.

Capote names names

Many — even most — writers borrow from their own life experiences, Truman Capote included. The problem with "La Côte Basque 1965" was that he borrowed (to put it generously) from the lives of others. He had the courtesy (again, a generous interpretation) to use made-up monikers in the cases of Slim Keith, Ann Woodward, and Babe Paley, but he wrote more of his friends into the story using their real names and situations.

Capote had dirt on Maureen Stapleton, Princess Margaret, Gloria Vanderbilt, Joanne Carson, and then some, and he used it as fodder for P.B. Jones and Lady Ina Coolbirth's imagined lunchtime chat. Through his characters, the observant author insinuated that Stapleton was in the midst of a nervous breakdown, that the Queen's sister was not only bigoted but boring, and that Vanderbilt's affections were so fleeting, she ran into and didn't recognize her first husband. He had a closer relationship with Joanne Carson, the wife of famed "The Tonight Show" host, Johnny Carson. Joanne also had a similarly troubled childhood, and Capote took it upon himself to counsel her in matters ranging from her look to her love life. In the privacy of their marriage, Johnny wasn't the affable presence he was on TV, which was knowledge Capote exploited in his writing.

Joanne and Johnny aren't mentioned by name in "La Côte Basque 1965," though there is a spat between a woman and her talk show host husband. In spite of what could be seen as Capote's betrayal, she remained devoted to her friend and cared for him until the end of his life.

Lee Radziwill stays Lee Radziwill

One Swan who appeared as herself in "La Côte Basque 1965" was Lee Radziwill. Radziwill was the younger sister of Jacqueline Kennedy who, after divorcing her first husband, had married a Polish prince and had thus (in title but not power) surpassed Jackie's rank of first lady by becoming a princess. Once they'd met, she and Truman Capote were practically inseparable. He even attempted to make her a movie star; she appeared in a film that he wrote titled "Laura," but her performance was not well-received, and she gave up her acting ambitions.

Capote preferred Radziwill to her more famous older sister, which comes across in "La Côte Basque 1965" when Lady Coolbirth favorably compares Lee to Jackie. Unlike Slim Keith and Babe Paley, Radziwill didn't cut Capote out of her life after the chapter hit the magazine stands, probably because she didn't mind how she was portrayed. But that doesn't mean their friendship didn't suffer. The majority of the Swans were appalled, and Capote became persona non grata within his former clique. In the lead-up to the excerpts' publication, he'd been throwing balls attended by friends like Radziwill. In the aftermath, his star power had significantly diminished. That, combined with his troublesome inability to keep a secret, strained his relationship with the princess, whose title he took to using mockingly.

C.Z. Guest stays by his side

While Truman Capote tapped the lives of his many celebrity friends and acquaintances for what was to be his masterwork, curiously, he left one Swan out. At least none of the characters or circumstances in "La Côte Basque 1965" brought her to mind enough for the public to make educated guesses.

C.Z. Guest (her initials are the product of a childhood mispronunciation of the word "sister") was a Renaissance woman. She became a muse to artists like Diego Rivera, Andy Warhol, and Salvador Dalí. She designed clothes, rode horses, gardened, and married a Churchill — Winston Frederick Churchill Guest — to whom Ernest Hemingway was best man at their wedding. Guest was exactly the type of female friend Capote courted. But for reasons unknown, the author chose not to overtly allude to her in his project about high society's most intimate goings on.

When the story was printed, she had no reason to shun him. In fact, she and her husband tried their best to get the self-destructive author the help he needed, as his life spiraled out of control after "La Côte Basque 1965" backfired so spectacularly. The Guests arranged for a reluctant Capote to enter a rehabilitation facility for drug addiction. But by then, the writing was on the wall, and the writer's downfall was imminent.

Unanswered prayers

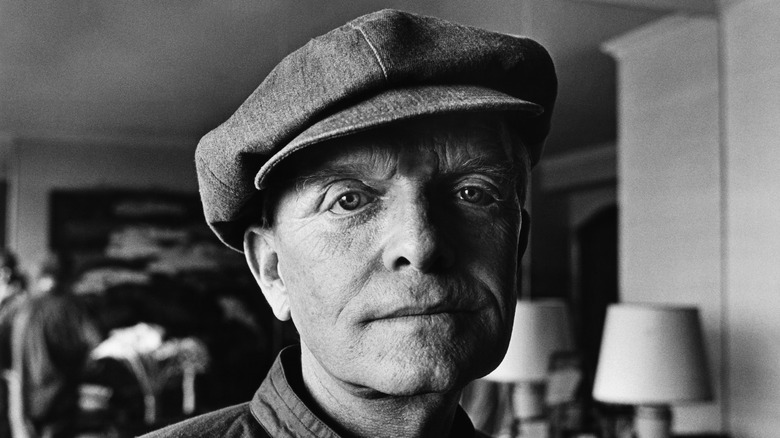

With "Answered Prayers," Truman Capote hoped he'd have something profound to say. He'd wanted to mix the high brow with the low brow, and pay homage to the women he so admired and spent so much of his time with, all while dissecting their vanity and hypocrisy. But, in a case of life imitating art, Capote exposed his own faults in the misbegotten concept of — and failure to complete — his would-be novel. Just a few months after "La Côte Basque 1965" was published in November 1975, a scathing summary of the scandal that Capote had stirred was printed in New York Magazine, which ran under the headline "Capote bites the hands that fed him," alongside a grotesque cartoon.

In the years that followed, Capote increasingly indulged in drugs and drink, which didn't go unnoticed in the public eye. His relationship with his nearly lifelong partner, John Dunphy, became dysfunctional and violent. His final years were marred by writer's block, addiction, and paranoia, and he spent them in and out of hospitals and the homes of concerned but ever more impatient loved ones. Capote died in the presence of his friend Joanne Carson in August 1984. He was not quite 60 years old.

Ironically, though the Swans suffered in the pages of "La Côte Basque 1965" and after its publication, too, the adage that had so fascinated Capote came to apply most of all to himself. Through talent, chance-taking, and masterful mingling, that anxious, lonely boy from Monroeville, Alabama, had become as important, respected, and celebrated as he could've ever hoped to be. But in the end, his own answered prayers ultimately led to his demise.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, is struggling or in crisis, contact the relevant resources below:

-

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

-

Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org