Politicians Who Were Assassinated In The 21st Century

Political assassinations are nothing new in the history of the world — the 21st century has seen quite a few of them, mostly in the Middle East and South Asia, as well as the North Caucasus, Africa, and the U.S.-Mexico border, where drug cartel-induced violence runs rampant. They range from local officials who fought organized crime to presidents and prime ministers, the highest profile being Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

While some of the assassinations on this list — like Shinzo Abe — appear to have been the work of lone wolves or countries settling old scores, one cannot help but notice the inordinate number of politicians who were killed by members of paramilitary groups. Most often, the killers have been affiliated with extremist organizations, organized crime and drug smuggling, or other non-state actors. Here are 16 politicians who were assassinated in the 21st century, and the oft-complex circumstances that led to their deaths.

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto, daughter of former Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was the first woman to become Pakistan's prime minister, serving two stints between 1988-90 and 1993-96. Following her second tenure, a 1999 military coup by General Pervez Musharraf, combined with corruption allegations and potential jail time, sent her into exile. She returned home in 2007, where she met her end a mere two months after stepping off the plane.

Bhutto returned to Pakistan after Musharraf pardoned her over the corruption allegations, and the assassination attempts began almost immediately. In Karachi, two suicide bombers struck her motorcade, missing her, but killing over 130. A second suicide attack by a 15-year-old boy in Rawalpindi, however, killed her alongside 20 others. Her supporters pointed fingers at the Pakistani government and terror organizations, while the government initially blamed security failures and the Pakistani Taliban, who denied all involvement.

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Agency eventually accused Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden of providing the explosives. This is plausible, as Bhutto told Al-Jazeera's David Frost that the Afghan mujahideen – allies of the terror leader – had attempted to kill her in the 90s. But such an operation would probably not have succeeded without inside help. Thus, it is believed terror groups and anti-Bhutto elements within Pakistan's security apparatus cooperated to kill her. Bhutto's relatives told the BBC the complicity extends to Musharraf himself, accusing the former president of reducing Bhutto's security. Pakistan has since charged Musharraf with the killing and considers him a fugitive from justice.

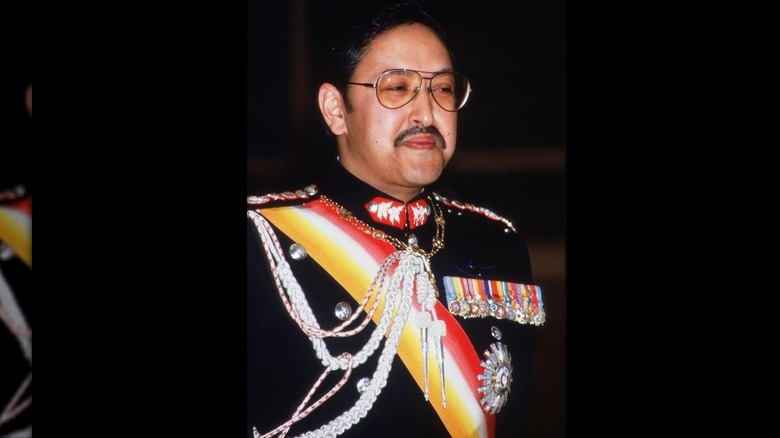

King Birendra of Nepal

King Birendra ruled Nepal from 1972 until 2001, overseeing a messy transition from a centralized monarchy to a more democratic, constitutional system between 1990 and 2000. In 2001, however, he was gunned down alongside eight other members of the Nepalese royal family in one of the worst political massacres of the 21st century.

The killings shocked Nepal, as the king was considered an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu – killing him was considered sacrilege. Most tragically, the killer was Birendra's own son, Crown Prince Dipendra, a publicly beloved figure who had his personal struggles behind the scenes. Lieutenant General Vivek Kumar Shah, a royal insider and confidant of both men, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation that the crown prince's relationship with his parents – already strained since childhood – truly bottomed out when Birendra and his queen Aishwarya (Dipendra's mother) refused to let Dipendra marry Nepali noblewoman Devyani Rana, whom he had met while studying at Eton in the U.K.

As the issue spilled into the papers, Dipendra's status as heir came into question, and it seems he cracked under pressure. After consuming a cocktail of drugs and alcohol, he broke into a royal dinner and massacred his relatives, including his father, his mother, and even his younger brother, before attempting death by suicide. Birendra's death was the beginning of the end for the Nepalese royal family, which lost its position after a 2008 republican uprising ousted Birendra's brother Gyanendra and abolished the monarchy.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Shinzo Abe

Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had pursued a containment policy against the economic rise of the People's Republic of China through a series of military and economic reforms, including attempts to alter the country's pacifist constitution to allow the Japanese military to operate abroad in non-peacekeeping roles for the first time since World War II. Still active in politics after stepping down as prime minister in 2020, his agenda ended in 2022, when a gunman shot him dead in the city of Nara.

Japanese officials quickly got the killing's motive. The shooter, Tetsuya Yamagami, had targeted Korean religious leader Hak Ja Han Moon, head of the controversial Unification Church — an organization frequently labeled a cult. In a letter reportedly sent to an unnamed recipient and obtained by Japanese outlet Kyodo News, Yamagami said his mother had donated much of the family wealth to the church, allegedly ruining the family finances. His uncle confirmed she had donated around $720,000, and that the resulting money problems forced Yamagami — otherwise a hard-working individual — to ditch college.

When Yamagami was unable to shoot Moon due to COVID-19 restrictions, he targeted Abe instead. Abe's grandfather, former Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, had helped establish the group's anti-communist political wing, to which Abe maintained close links. Killing Abe was a sort of revenge by proxy. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida's government has since sought to dissolve the Unification Church's Japanese branch following the assassination over concerns it wields too much influence. The organization has denied all wrongdoing.

Jovenel Moise

The tenure of late Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was turbulent to say the least, as his administration wrestled with poverty, instability, and gang violence – the latter of which he was accused of allowing to run rampant. His 2021 assassination, which occurred at his house in the Pelerin 5 area of Port-au-Prince at the hands of a handful of ex-Colombian soldiers, only worsened the situation.

A U.S.-led investigation charged citizens of three different countries with the killing, which is believed to have been part of a larger regime change plan by Moïse's rivals. Originally, the plot was to arrest Moïse and remove him from office. Once kidnapping was deemed logistically impossible, the plotters allegedly had a group of ex-Colombian soldiers, allegedly hired through Florida-based private security company CTU, to carry out the hit.

Initially, prosecutors suspected Haitian-American doctor Christian Emmanuel Sanon, who allegedly wanted to be Haiti's president, of leading the plot. Federal prosecutors alleged Sanon discussed regime change in Haiti with another conspirator named James Solages. The plotters, however, reportedly decided Sanon was a poor replacement for Moïse and settled on someone else, leading Sanon's associates to claim he was set up. In 2023, Haitian Rodolphe Jaar pleaded guilty to providing money for the weapons used in the assassination, but this still leaves the question of who pulled the strings. Sanon's claims of being a patsy cast suspicion on Haitian Senator Jean Joel Joseph, the highest-ranking person to be charged.

Adilgerei Magomedtagirov

Dagestani Interior Minister Adilgerei Magomedtagirov was shot dead by a sniper at a wedding alongside four policemen, including the father of the bride. He was yet another victim of paramilitary violence in Russia's simmering North Caucasus, where Islamic militancy, the Chechen Wars, organized crime, corruption, and ethno-religious conflict made it a dangerous place to govern. In 2009, the unrest spread to Dagestan, the mountain republic bordering the western shore of the Caspian Sea. The republic witnessed near-daily attacks against government and law-enforcement figures, of which Magomedtagirov's was the highest-profile incident.

Federal authorities convicted former Russian soldier Andrei Rezanov for the killing. According to the Russian Investigative Committee looking into the case (via The Moscow Times), Rezanov shot Magomedtagirov for a payment of nearly $46,000, reportedly without even knowing the victim's identity. After Rezanov's conviction, Russian authorities sought his paymaster, reportedly Dagestani warlord Ibragim Gadzhidadayev.

Russian officials accused Gadzhidadayed of running an extortion scheme that had ensnared over half of Dagestan's officials, presumably through blackmail or other kompromat. Magomedtagirov's killing suggests he was not only not compromised, but also posed a threat to the militancy's future. He was known for his ruthless attitude towards terrorists, suggesting the use of tactics similar to those in Ramzan Kadyrov's Chechnya, wherein the Chechen authorities target fugitives' families. Thus, killing him was likely a matter of self-preservation for Gadzhidadayev and his operation. But eventually, he too was killed in a raid against the town of Semender.

Shahbaz Bhatti

Pakistan's Minister for Minority Affairs Shahbaz Bhatti (pictured above left) – a Catholic and the only Christian in the federal cabinet — was shot dead in 2011 by the Pakistani Taliban for his opposition to the country's vague and oft-abused blasphemy laws. The laws criminalize all remarks that are offensive – or could be taken as such – to the Prophet Muhammad. But because they are so broad, members of Pakistan's Sunni majority have often used them to settle personal vendettas with non-Muslims, Shias, and even each other. Accusations are often met with vigilante justice and death at the hands of a mob. In 2009, a Christian mother named Asia Noreen (better known as Asia Bibi) nearly suffered this fate after her neighbors falsely accused her of blasphemy.

According to human rights lawyer and Bhatti acquaintance Knox Thames (writing in Christianity Today), Bhatti leveraged every contact – particularly in Washington, D.C., to get Bibi released. Pakistani extremists were not pleased: Bhatti had already received death threats for his activism, but the threats became real once the Bibi case went global. He got a stark warning when Punjab Governor Salman Taseer was shot dead in January 2011, for demanding Bibi's release. Bhatti's death followed a mere two months later, and currently remains unsolved. Because of his courage, exemplary life, and anti-extremist activism on behalf of all Pakistanis, the Catholic Church has opened a cause of beatification for him as a martyr for the faith.

[Featured image by Zolnakerviquemolbec via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Akhmad Kadyrov

Akhmad Kadyrov was a former commander for the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, a state that seceded from the Russian Federation in 1991 following the collapse of the USSR. But as extremist Wahhabi elements funded with Saudi oil money gradually took over the majority-Muslim state's leadership, Kadyrov flipped and went over to Russian President Vladimir Putin. With Moscow's support, Kadyrov became president of Chechnya in 2000.

Kadyrov's cooperation with Russia and his iron-fisted rule, which included accusations of kidnapping and disappearing opponents, made him a target for paramilitary groups who struck back in 2004. That year, a bomb planted in the VIP box of Grozny's stadium during a Victory Day celebration killed Kadyrov and five others, and wounded 60 more. According to the Russian outlet Izvestia (via NBC News), Russian authorities said someone in the employees-only area of the stadium activated the bomb, meaning the perpetrator was either a stadium employee or was let in by one — a sign Kadyrov may have faced popular resentment.

Who funded the hit? Russia accused Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev, mastermind of the Beslan School Siege. He reportedly claimed to have paid the perpetrators $50,000 for the hit. Others blamed Russia for killing Kadyrov to prevent him from taking over Chechnya's oilfields. Ramzan Kadyrov, Akhmad's son and current Chechen leader, however, blamed rebel commander Sulim Yamadayev, who was himself assassinated in a Dubai bomb attack. The exact perpetrators remain unknown, and political considerations in the North Caucasus make it unlikely the truth will be known any time soon.

Eunice Dwumfour

Republican Councilwoman Eunice Dwumfour (pictured above at her wedding) of Sayreville, New Jersey, was found dead in her car outside her home in February, 2023. Investigators concluded a gunman had waited outside her home, ambushed her, and shot her 14 times. They found a 9mm Glock pistol, which they traced back to a man named Rashid Ali Bynum. After concluding the bullets and casing found at the scene likely came from that gun, Bynum was charged with murder.

Prosecutors allege Bynum drove all the way from Virginia to kill the councilwoman, whom he knew from a Bible study group. The full picture of Dwumfour's relationship with Bynum is unclear, but prosecutors say Dwumfour brought him into her church's community when he was down on his luck. Bynum even lived with Dwumfour for a time at her house, where she sheltered people facing life struggles. Eventually, however, Bynum left the church for unspecified reasons and returned to Virginia, according to the prosecutors, which suggested a personal motive in the killing — if Bynum did it.

Bynum has pleaded not guilty to all charges. His lawyer has argued that no witnesses saw him at the crime scene and denied any personal motive for killing Dwumfour. The prosecution alleges phone records place Bynum in the vicinity of the crime scene at the time the killing took place. As of early 2024, the trial is ongoing.

Andrew Pennington

Andrew Pennington, who served as a councilor for Gloucester County, England, was killed in 2000 when an angry local man attacked his boss, Member of Parliament Nigel Jones, with a samurai sword, at the Liberal Democrat Party's HQ. Pennington jumped in to try and protect Jones, but was stabbed six times. The killer, a local man and father of two named Robert Ashman, was convicted of manslaughter rather than murder due to his mental condition.

Ashman's motives were murky. On the day of the attack, he had said, according to The Independent, that he "went to see Mr Jones to frighten him and find the truth," but not with the intention to kill him, a motivation seemingly related to his mental issues. He blamed Jones for not helping him get back on his feet, but also accused local law enforcement of harassing him for no reason. Ashman's state had deteriorated after he suffered a series of serious life setbacks, including bankruptcy, a job loss, and a divorce.

According to Detective Superintendent Wayne Murdock, per The Independent, Pennington's heroic actions ended up saving Jones' life, posthumously earning him the George Medal – a civilian honor given for heroism. Ashman was released from prison in 2012 after serving eight years, after authorities deemed him no longer a threat.

Zoran Dindic

Serbia's Zoran Dindic (pictured above left), the country's first democratically-elected prime minister, was shot dead in 2003, by at least two gunmen, as he exited his armored car. He led opposition to Slobodan Milosevic's disastrous 13-year rule, which saw Yugoslavia disintegrate in a series of bloody wars amid the proliferation of organized crime and corruption. Dindic ousted Milosevic in a shock election in 2000, and extradited the former leader to the Hague's International Criminal Court to face war crimes charges. He also sought Serbian rapprochement with the United States and NATO – a major shift following the 1999 NATO Christmas Bombing of Belgrade.

Dindic's killing occurred at the confluence of Serbian political rivalries and organized crime. According to Serbian academic Srdjan Cvijic (via Balkan Insight), Dindic prioritized curbing organized crime, whose leaders, rich from wartime profiteering, smuggling, and other illicit activity, had bought their way into respectable Serbian society and politics during the Milosevic years. Dindic's arrival threatened their positions and the immunity from prosecution that their connections undoubtedly gave them. As for Milosevic holdovers, Đinđić's extradition of their old boss for war crimes meant they could be next.

These different factions joined together against Dindic, as evidenced by the fact that, of the 12 defendants convicted in 2007, two were former elite Milosevic paramilitary commanders in the Croatian and Bosnian wars.

[Featured image by Demokratska Stranka via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Rafik Hariri

Former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was killed when a car bomb blew up his motorcade near Beirut's St. George Hotel in February, 2005. Harari opposed Syria's occupation of Lebanon, which had begun in 1976. As a counter, he courted American-backed Arab states like Saudi Arabia, which helped him get elected in 1992 and bankrolled Lebanon's post-civil war rebuilding. In 2005, he ran on enforcing UN Resolution 1959, which called on Syria to withdraw from Lebanon, setting up a clash with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Syria and Iran, via the terror group Hezbollah, are the chief suspects behind the assassination. The region's ever-shifting geopolitics gave them a motive: Hariri's pro-American stance by proxy through his Saudi relationship threatened Syria's – and by extension, Saudi-American rival Iran's – position in the region. In the worst-case scenario, Assad feared Lebanon would become a springboard for an American regime-change war in Syria. But, the killing backfired spectacularly. Hariri's death united Lebanon's numerous faiths against a common foe as the Cedar Revolution – mass protests against Syrian occupation – broke out immediately following the assassination. By April, 2005 – a mere two months after Hariri's death – Syrian forces were pulling out of Lebanon.

Jesús Manuel Lara

In 2010, Jesús Manuel Lara, mayor of the border town of Guadalupe Bravos (near the Ciudad Juárez-El Paso port of entry), paid the ultimate price for his opposition to cartel violence when he was shot dead in front of his family. Lara was already on the cartels' radar for his attempts to bring order to Guadalupe. However, his police force of 40 officers, upon whom his project relied, dwindled to a mere four as men quit the force, presumably in the face of cartel death threats. As threats against his person escalated, he moved his family to Ciudad Juárez – one of the most dangerous cities in the Americas – where his political partner, Jose Reyes Ferriz, was mayor. He was killed soon after.

Lara's killing was a classic example of the help-us-or-die politics that rule on the U.S.-Mexico border. Politicians on both sides of the border face the stark choice of ignoring or aiding the violence, or risking kidnapping, torture, and death for opposing it – sometimes with the complicity of the Mexican army and local law enforcement. Lara's death gave some hints in this regard. According to Ferriz, as reported by CNN, Lara never requested any official protection, although his position as border mayor and previous threats certainly qualified him for it. He never even informed Ferriz of his presence in Ciudad Juárez. As of early 2024, his murder remains unsolved.

João Bernardo Vieira

Joao Bernardo Vieira (pictured above) governed the West African nation of Guinea Bissau from 2005 until 2009, when the army ousted and killed him in a palace coup d'etat. The overthrow resulted from a rivalry between Vieira and the military, after several Guinean soldiers and General Battista Na Waie were killed in a bomb attack against the latter's headquarters in March 2009. Na Waie had accused Vieira of attempted murder in the past (and vice-versa), threatening that if he died, Vieira would follow. True to form, his supporters, believing Vieira to be behind the hit, attacked, tortured, and killed the president hours later with machetes.

Although the killing seemed to stem from a personal feud, there were bigger issues at hand. A Guinean official suggested to Reuters that ethnic rivalry between two groups — Vieira's Papel and Na Waie's Balanta — may have played a part. However, according to Georg Eckert Institute fellow Christoph Kohl, writing in the journal Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, ethnic division in Guinea-Bissau is quite rare. Add drug trafficking to the picture, though, and a more believable motive surfaces.

Guinea-Bissau is known as Africa's first narco-state, having a reputation as a haven for cocaine trafficking to Europe from Latin America. Cartels and the trade have infiltrated the government up to the top military brass and the presidency, and may have been influential in Na Waie and Vieira's feud and their subsequent deaths.

Idriss Deby

Modern politicians don't generally go to war, but Chadian President Idriss Deby was an exception. This key Western ally against Islamist terror groups in Africa's Sahel region was killed on the battlefield while fighting rebels who wanted him overthrown. Four-hundred fifty-four rebels have gone on trial in Chad on assassination charges related to Deby's death, as well as on accusations of using child soldiers. As of early 2024, the country is being governed by a transition government under his son and successor, Mahamat, who has promised to hold elections in 2025.

As usual, there was the killers' stated motive and a more probable ulterior motive. The rebels, known as the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT), justified their actions with concerns he would turn Chad into a hereditary dictatorship (he held power for almost 30 years). Although FACT has presented itself as a pro-democracy movement, its foreign ties suggest there is more going on.

FACT reportedly obtained its weapons from Libyan General Khalifah Haftar and used Libya as a base to launch the attack that killed Deby. Haftar has, in turn, received backing from Russia, which suggests the rebels, who have allegedly received training from Wagner Group mercenaries, may be a vehicle for weakening the Western presence in Chad. The struggle for Chad — and Deby's death — may not simply be about global security or ideology – after all, it is an oil-rich nation.

Angelo Vassallo

The Italian region of Campania is known for its beauty, food, and organized crime – in this case, Naples' La Camorra mafia. The syndicate is known for all sorts of illicit activity, including construction rackets and drug trafficking. It either compromises or intimidates local officials into compliance, so governing in such an area has carried the risk of death for those who oppose the mafia, as Pollica Mayor Angelo Vassallo discovered in 2010.

Vassallo defied the mafia by fighting against overdevelopment, which dovetailed into multiple crimes and scams. One of them was over-development through contracts that were handed out (no doubt with La Camorra getting its cut) for building on some of Italy's most beautiful coastline. Since these contracts often ignored local laws and regulations, they required the complicity of corrupt officials to go through. Then there was the issue of "ghost streets" – contracts paid out for local infrastructure improvements that were never built. Finally, Vassallo was about to expose a Camorra drug-running operation out of the port of Acciaroli, which also implicated local law enforcement and politicians. Since he wasn't playing ball with the region's entrenched corruption, he was shot nine times.

The investigation appears to have been compromised from the beginning, allegedly due to local corruption. Nine people were investigated, including members of local law enforcement allegedly linked to La Camorra, but the murder appears to be officially unsolved as of early 2024.

Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev

Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev served as president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria from 1996-97. His main contribution to the Chechen movement was eschewing Western support in favor of courting Muslim nations – the Chechens' co-religionists – for aid, hoping to attract foreign money and fighters to Chechnya in a jihad against Russian rule. The tactics, however, failed to secure recognition of Chechnya as an independent state from anyone other than Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. Nevertheless, his activities and links to international jihadist networks landed him on Russian and Western anti-terror lists, leading him to seek refuge in Qatar with the country's ruling Al-Thani family.

Qatar, however, did not prove to be a safe refuge for Yandarbiyev. According to Qatari authorities (per NBC), he was killed in a bomb attack, to which Russia initially did not comment. When Qatar charged two Russian attaches at the Doha embassy, Russia played diplomatic hardball and arrested two Qatari athletes, while politicians demanded a military operation to get the operatives out. Moscow denied any wrongdoing, saying the agents were counter-terror operatives who had been framed.

The two men were ultimately convicted of killing Yandarbiyev on the Kremlin's orders and received life sentences. However, because Qatar did not want to risk relations with Russia, it released both of them with the expectation that they would serve their sentences in a Russian prison. It appears they have since been released, as the Russian Justice Ministry has no information regarding their whereabouts.