The Biggest Lies The Catholic Church Has Ever Told

It's no wonder that the claims of the Catholic Church have gotten seriously tangled over the years. With a centuries-long history that, according to some estimations, adds up to nearly two millennia of goings-on, there's a lot of doctrinal statements, events, and historical missteps to comb through. As critics of the church often maintain, the church's stance on a variety of issues has sometimes become so obscured that they can only call it what it is: a lie.

It's true that the institution's long history with such a great diversity of players has produced plenty of potential falsehoods. Some of these are easily framed as outright lies uttered by representatives of the church. Others may be more rightfully considered lies of omission or obfuscation, such as when church leaders have handwaved old dust-ups, like allowing Joan of Arc to be burned at the stake.

To be clear, these aren't all necessarily lies that the modern Catholic Church is telling. Neither should anyone claim that all Catholics everywhere wholeheartedly believe in the claims of church officials. Plenty of faithful people throughout history have butted heads with church orthodoxy, from English translator William Tyndale to Saint Joan of Arc. And none of this should be taken as a statement of faith or disbelief — your religious leanings are up to you.

The Catholic Church never sold indulgences

According to the advocacy group Catholic Answers, the church has never, not even once, been okay with the selling of indulgences. Yet the history of this practice makes that answer less clear. It all arguably starts with original sin, a Catholic doctrine that maintains all human beings are born carrying the weight of sin first incurred by Adam and Eve's rebellion. To deal with that sin, the church says, people must feel genuine remorse, confess, and repent. This doctrine, first fully articulated in medieval Europe, also states that souls may need some sort of divine retribution to fully clear the spiritual air.

Indulgences, issued by priests to balance out that need for punishment, were first made official by Pope Clement VI in 1343. An indulgence purchaser could help lighten their divine punishment or that of others, including the dead who might be suffering in purgatory. Officially, a buyer might be considered to be donating to a cause or project and getting an indulgence as a benefit. But, much like crowdfunding projects today, it's really just one step removed from buying something directly. The sale of indulgences was banned by Pope Pius V in 1567.

However, that didn't fully banish indulgences. Today, faithful Catholics might still hope to be granted indulgences on special occasions, by praying, or by doing good deeds (like donating to a charity). Yet the Church's stance is that money should never be directly exchanged for an indulgence.

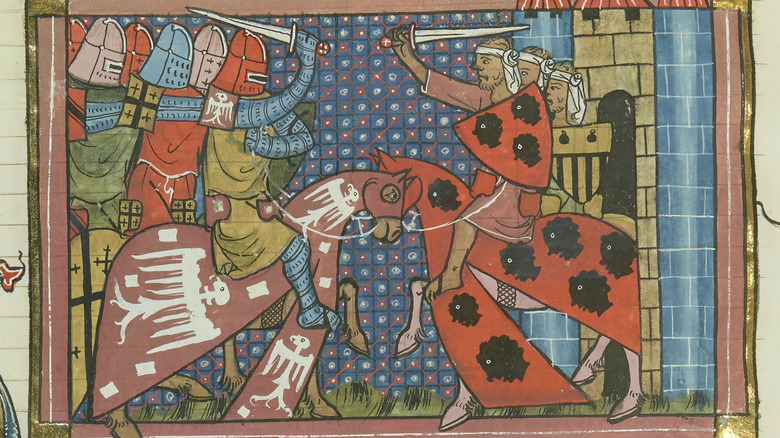

The Crusades were morally justified

One of the first Crusades ever was kicked off by Pope Urban II, whose speech at the 1095 Council of Clermont pinned the Muslim occupants of Jerusalem and beyond with horrid anti-Christian acts. As Urban painted it, going on crusade to liberate the Holy Land was a Christian duty.

But medieval people going on crusade didn't all share the same high-minded spiritual motivations. The Crusades, which periodically happened from the 11th to the 16th centuries, became an engine for supporting the Catholic Church in a very earth-bound financial, political, and military sense. Crusaders were also typically considered to be on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land — admittedly with plenty of fighting and pillaging along the way. They were making a trip that could score them an indulgence that partially or fully cleared their deck of sins. Back in the early days, in 1095, Pope Urban II promised all Crusaders full plenary indulgences – in other words, a full pardon on punishment due to sin. Eventually, those who simply donated to a Crusade without bothering to go on one could get indulgences, too.

Yet, the nasty reputation medieval Christians gave Muslims doesn't quite hold up. Many medieval Muslim scholars and communities were well-known for their intellectual achievements, while the history of the region shows more diversity and relatively (though not perfectly) peaceful coexistence than Urban II and his compatriots would have had you believe. And, as Muslim rulers like the 12th-century Saladin would have surely argued, the Islamic response to Western Christian invaders was plenty justified.

Claiming that Galileo was wrong

Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei had a pretty terrible go of things in 1633. On April 12 of that year, he faced a church-backed inquisition because he claimed that the Earth orbited the Sun, instead of the other way around. However, the church took exception to this notion, which knocked humanity and God's creation out of the literal center of existence. Such thinking, according to church fathers, was heresy.

It wasn't as if Galileo was the first to propose the theory. Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus wrote as much in 1543, but his ideas remained theoretical until Galileo observed the moons of Jupiter — awkward, since everything was supposed to orbit only the Sun, according to the church. Though the church had deemed the Copernican theory heresy in 1616, Galileo was able to study it as long as he promised the pope to stop short of supporting it.

But his studies were just too conclusive. Inquisitors ultimately decided that Galileo was guilty and banned his writings. To save his own life, Galileo agreed to keep his heliocentric ideas to himself and remained under house arrest until his death on January 8, 1642.

Though many later scientists backed up Galileo's theory, the Catholic Church didn't get around to admitting it had been wrong until 1992. More than three centuries after the tumultuous trial of Galileo, the Vatican took on a 13-year investigation of the matter, ultimately concluding that church officials had been wrong and officially clearing Galileo's name.

The church did everything it could to save people during the Holocaust

Pope Pius XII, the head of the Catholic Church from March 1939 to October 1958, officially took a neutral stance on World War II. Pius even played nice with Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler because he was reportedly worried that taking a stronger stance would push Catholics away from the church. Yet he oversaw economic aid to Jewish people, while thousands of Jews hid from persecution on Vatican land and emigrated with church assistance.

However, other church officials were close with Nazis and endorsed antisemitism, with some even working to clear the names of Nazi war criminals (in part because Nazis didn't completely upend the Vatican and its treasures when they occupied the city in 1943). At least Pope Francis more or less admitted that when he made Holocaust-era records open to the public in March 2019, saying in a speech that "the church is not afraid of history" and that he welcomed "appropriate criticism" of Pius and church actions during World War II (via Reuters).

Then, in 2023, a letter uncovered in the Vatican's archives came to light, indicating that Pius XII knew about the Holocaust by 1942. In the letter, anti-Nazi Father Lother Koenig, working in Germany, told the pope's secretary, Father Robert Leiber, that thousands of people were being killed every day by Nazis at the Belzec concentration camp. Koenig's letter also references the Auschwitz and Dachau camps. Yet, Pius, who probably saw the letter, remained quiet.

The Inquisition was only about faith

Whether you know about it from history class or an absurdist Monty Python sketch, you've heard about the Inquisition. Officially, it was a massive church-backed effort to uncover and stamp out heresy that started in Europe and then crossed the Atlantic to the European colonies in the Americas. The most notorious is the Spanish Inquisition, which worked in Spain for over two centuries, though the larger Inquisition spanned from the 12th century into the 1800s. Besides ferreting out anti-establishment thinkers, the Inquisition also targeted non-Christians, including Muslims who had previously occupied Spain and Portugal, as well as Jewish people. Jews who converted to Christianity still faced suspicion of being Marranos, or secret Jews who could still somehow upend the church. In later centuries, the growing numbers of Protestant Christians also sparked inquisitions and executions.

But was all of this about holding up the Catholic faith, as church leaders so often maintained? For some, it certainly was, but this was not the only force driving centuries of this heresy anxiety. The 15th-century co-rulers of Spain, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, must have recognized that their political and religious powers were inextricably linked. Pushing out competing religious groups like Jews and Muslims allowed them to consolidate that power. Moreover, if someone was found to be a Marrano (also known as Conversos), the crown could seize their wealth and use the money for its own purposes ... like a crusade against the Muslims still occupying the Iberian Peninsula.

That women have no place being ordained

Some Catholics argue that it's fine for a woman to deliver a homily, while others may find themselves aghast at the notion. Ordination, the process of joining the clergy, remains closed to Catholic women. As Pope Francis told America magazine in 2022, it simply is not a woman's place. Instead, he countered, they should focus on the "Marian principle" with its emphasis (literally or metaphorically) on motherhood and wifehood. His words are hardly surprising, given the long line of popes saying the same thing.

But women have preached to Christians before. One of the earliest was Mary Magdalene, who was the first to inform the Apostles of Jesus' resurrection in Mark 16:9-10. Other Gospels maintain that women were the first to preach the resurrection, though the exact lineup varies depending on the account. Later, in Acts 18:24-46, Priscilla and Aquila welcome a learned religious man into their home and "expounded unto him the way of God more perfectly." Then, there's the unnamed Samaritan woman who, after having met with Christ at a well, effectively preached to men of her city to follow him (via John 4:28-30).

It's worth noting that the earliest clear evidence of Christian ordination is from the third century. Earlier texts hint at the practice, but it was hardly the widespread and clearly defined process the church employs today. Given that, alongside the Biblical evidence, it may seem all the more strange that women are still blocked from the priesthood.

Cleaning up its take on Joan of Arc

When she was facing execution on May 30, 1431, Joan of Arc probably did not feel loved by the Catholic Church. Any medieval trial for heresy would have made you think that, especially if it ended with being burned at the stake. Of course, church officials didn't have much love lost for the 19-year-old French visionary, who claimed that she directly spoke to the saints without a priest's help. She then used her religious encounters to get in good with the heir of France and lead military campaigns against invading English forces.

When Joan was captured by English-allied Burgundians in May 1430, she was put on trial for heresy. After being found guilty — for dressing in men's clothes, though other heresy charges did not officially stick — Joan was effectively turned over to secular authorities to be burned at the stake.

Today, however, you may notice that Joan is now more properly referred to as Saint Joan of Arc. Twenty years after her death, a retrial ordered by the French king (who benefited from her help but didn't do much to save her when she became politically inconvenient) overturned the charges. Over the following years, Joan's acclaim grew, and in 1920 she was canonized by Pope Benedict XV. Now, she's the namesake of quite a few churches and nice statues, while standing as the patron saint of France. For the uninformed, it may seem like the church has always been cool with Joan.

Church officials covered up sexual abuse

Of all of the lies linked to the Catholic Church, one of the most painful is its world-spanning, generations-long coverup of sexual abuse perpetrated by some of its priests. Reports of abuse can be traced back to the mid-20th century, but a 2002 report from the Boston Globe brought the issue to a breaking point. Two years later, a church investigation found that over 4,000 priests in the United States alone had been accused of abusing more than 10,000 children. Reports from other countries, including Ireland, Australia, Germany, and France, found much the same.

As the Boston Globe discovered, only a tiny number of priests in the Archdiocese of Boston had faced criminal charges by 2002. Instead, the church typically resorted to paying victims off and removing or reassigning priests. Some accused clergy were placed in ministries that ostensibly kept them away from minors, but others were moved to new parishes where they could continue their abuse.

The problem was rampant in other dioceses. In Albany, New York, Bishop Howard Hubbard — facing abuse allegations himself — admitted in a 2021 deposition that he had never reported serious allegations of sexual abuse to authorities, citing worries about "the respect of the priesthood" (via The Guardian). And in Baltimore, Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown issued a 2023 report that claimed the church covered up abuse of more than 600 children by 156 clergy.

That purgatory has always been a thing

Today, purgatory may seem like a set-in-stone aspect of Catholic theology. When consulted on the matter, apologists point to church doctrine that says souls must be purified before entering Heaven, as well as key Bible verses. Revelation 21:27 maintains "there shall in no wise enter into it [Heaven] any thing that defileth," for instance. For many faithful, that's reason enough to accept purgatory, where souls experience a kind of temporary Hell before making it to Heaven.

But, despite bits of scripture that may hint at the concept, none of the books of the Bible directly mention purgatory. Instead, purgatory is a medieval idea born out of generations of debate and anxiety. It was first summed up by 12th-century theologian Peter Lombard, whose "Sentences" sought to synthesize many preceding arguments, as well as the competing concepts of innately sinful humanity and the hope of Heaven. Lombard used Aristotelian logic to make his conclusions, drawing on the work of a pre-Christian philosopher whose work was nevertheless central to medieval European thought.

Soon enough, the concept of purgatory caught on, with later theologians even coming up with detailed lists of sins and the length of time each wrongdoing would add to one's time in purgatory. On the other side of the scale, good deeds, prayer, and engaging in sacraments (like confession and communion) were often thought to lessen a purgatorial stay. The whole idea wasn't strictly defined by the church until later in the 13th century.

That it's always been cool with English Bibles

Technically, the Catholic Church has only ever opposed unauthorized translations of the Bible. In that vein, it's not fair to pretend that early Bibles were completely inaccessible to non-clergy or only published in Latin. However, for most of the Middle Ages, debate raged about whether or not a full vernacular (non-Latin) translation was okay, with many landing on the side of Latin only and insisting on the use of a fourth-century Latin translation known as the Vulgate. Still, bits of the Bible were reworked into common languages in an attempt to connect with people who couldn't read Latin.

Then, splinter groups created their own potentially heretical translations. Rulers began to weigh in, as when Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV banned the use of vernacular Bibles in his kingdom in 1369. This notion became widespread by the 16th century when scholar William Tyndale started agitating for an English translation of the Bible. When church authorities in England forbade it, Tyndale traveled to Germany, where he published a translation of the New Testament in 1525 and part of the Old Testament in 1530. He was finally apprehended in Antwerp and executed in 1536.

Today, however, you might have a hard time finding Latin in any but the most conservative Catholic churches. After the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s, the church moved away from Latin and now is more likely to conduct services and hand out Bibles printed in a local language.

If you or anyone you know may be the victim of sexual assault or is dealing with spiritual abuse, contact the relevant resources below:

-

Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

-

Call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.