JFK's Death Couldn't Stop Him From Restoring J. Robert Oppenheimer's Name

Even J. Robert Oppenheimer's friends and colleagues conceded that he did himself no favors at the crucial moment. His impatience, arrogance, and a self-confessed inclination to lash out made him hard to like, and his naïveté in the realm of politics left him ill-prepared for the environment of the early Cold War. Just how much Oppenheimer's behavior hurt him was detailed in PBS's "The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer." He was privately insecure and doubtful of his moral worth. According to journalist and historian Priscilla McMillan, the scientist later said the experience of his security hearing left him feeling "repulsive" in his own eyes.

But whatever Oppenheimer's faults, the hearing that ultimately stripped his security clearance, effectively ended his public career, and broke him personally has come to be seen as a travesty born of the Red Scare. Even at the time, the treatment of a loyal American integral to the nation's atomic program drew outrage. Per the Los Alamos National Laboratory, nearly 500 scientists signed a petition protesting the decision and its potential impact on recruitment to defense laboratories and sent it to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

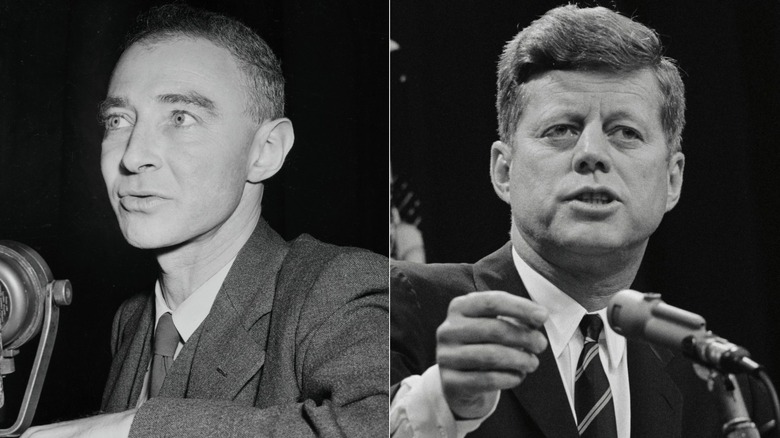

Eisenhower's administration took no action, and the decision of the security panel wouldn't be overturned until 2022. But within Oppenheimer's lifetime, efforts were made to restore his reputation, including by Eisenhower's successor. John F. Kennedy was not intimately associated with Oppenheimer, but he did provide a crucial vote against one of the doctor's greatest enemies as a senator. As president he was preparing to bestow a high national honor on Oppenheimer before his assassination, and his efforts were not in vain.

As senator, Kennedy voted against Oppenheimer's enemy

John F. Kennedy's first involvement with J. Robert Oppenheimer was an indirect one. In 1958, when Kennedy was still serving in the U.S. Senate, Lewis Strauss was the acting secretary of commerce for the Eisenhower administration. Strauss had a long history of private commercial success and headed the Atomic Energy Commission for five years. He was also a vindictive and manipulative man who nursed a long grudge against Oppenheimer for humiliating him at a hearing and opposing the development of the hydrogen bomb.

It is now a matter of public record that Strauss used his contacts in the media and the FBI to savage Oppenheimer's standing in government and in the eyes of Dwight D. Eisenhower (detailed by History). The campaign culminated in the hearing that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance. Strauss' hand in the campaign against the scientist was brought to bear in his confirmation hearing before the Senate, necessary to win a permanent position as commerce secretary.

Reporting at the time by the Lewiston Daily Sun indicated that Kennedy was initially leaning toward voting in Strauss' favor. But in the nail-biting final vote, which went 46-49 against Strauss, the senator from Massachusetts was ultimately a nay. In his explanation, published in the Boston Globe, Kennedy did not mention Oppenheimer or the campaign against him. Instead, he was more upset by Strauss' supporters haranguing senators with furious lobbying and contradictory promises after the hearing. But it was still a crucial vote against the man who destroyed Oppenheimer's public career — a fate Strauss would share after his own hearing.

Kennedy planned to give Oppenheimer the Enrico Fermi Award (and Johnson did)

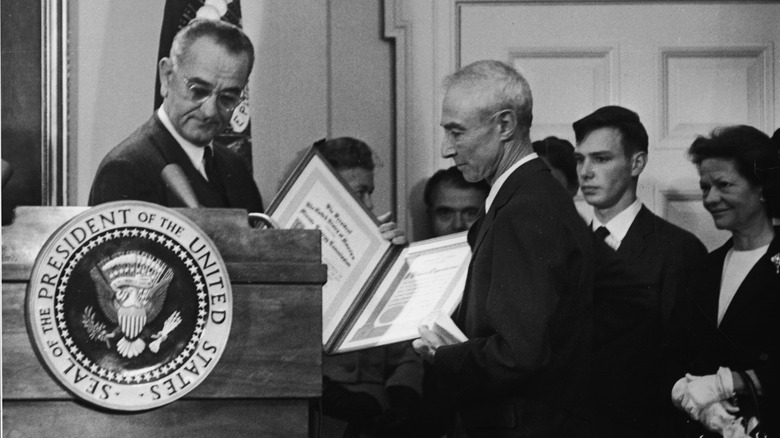

In April 1963, Science announced that J. Robert Oppenheimer would receive the Enrico Fermi Award for that year. The Fermi Award, established in 1956 by Dwight D. Eisenhower, is granted by the president for achievement in the areas of energy science and technology and comes with a generous cash prize. The scientific community saw Oppenheimer's selection for the award as a step toward repudiating the Cold War hysteria that had so wounded him.

Per USA Today, John F. Kennedy's scientific advisors had pushed him to bestow the honor on Oppenheimer. The president had signed the award and was prepared to personally give it to the doctor in a ceremony that December. Curiously, Oppenheimer himself wanted to decline the award. Per Priscilla Johnson's "The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer," he was put off by the fact that Edward Teller, who had testified against him, was given the prize the year before, and by the transparently political nature of the decision. But he ultimately felt obliged to accept.

Kennedy was assassinated just days before he was meant to present the award. But in one of Lyndon Johnson's first acts as president, he carried on with the ceremony and presented Oppenheimer with the award. Per The American Presidency Project, he acknowledged that the award was Kennedy's decision and expressed grief for his death. Oppenheimer remarked that it took "some charity and some courage" to award someone like him.