Some Scientists Believe We're Having Another Mass Extinction Right Now

As any schoolkid will tell you, the dinosaurs died out millions of years ago, killed off by a cataclysmic asteroid impact. In an instant, our planet was forever changed. Entire forests were incinerated. Immense tsunamis ravaged coastlines. Eventually, over 80% of all life on Earth was wiped out. This may be the best-known extinction event Earth has faced, but it's most certainly not the only one.

Over the eons, Earth has endured at least five mass extinctions, each coinciding with drastic changes in the environment. The formal definition of a mass extinction event, per National Geographic, is any time when at least 75% of Earth's species have been lost in a relatively short space of time. Exactly what caused these past events, however, is anything but certain, and there's a lot we still don't know. Scientists aren't even certain of the number of mass extinctions to have happened before now. Some argue, fairly convincingly, that there may have been six extinction events in Earth's past. And that, unsettlingly, our planet is in the midst of its seventh extinction event right now.

It's known as the Holocene extinction, with an increasing number of researchers convinced of its potentially dire consequences. One study in the journal PNAS states this with sobering certainty, describing it as a "rapid mutilation of the tree of life, where entire branches and the functions they perform are being lost." This time, however, the cause isn't as spectacular as a huge asteroid impact. This time, it's us. Humans.

The Holocene epoch

The history of planet Earth is subdivided into several chapters. Stories spanning billions of years, written in rock, known as epochs. Geologists and paleontologists refer to them when unraveling the events of the distant past. The current epoch is known as the Holocene. It began roughly 11,700 years ago, coinciding with the end of the last ice age. It also corresponds neatly with the rise of humanity.

As the ice age ended and Earth began to thaw, our distant ancestors' lives began to change. Roughly a millennium into the Holocene, humans began to leave the hunter-gatherer lifestyle behind and adopt sedentary lives. Villages formed and people began to take up farming. This was the start of the Neolithic period, or the "New" Stone Age, and it would lay the foundations for all the human civilizations that were to follow.

Even at the very start of the Holocene, animals began to quickly go extinct. Among the first to die off were megafauna, like woolly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers. While the changing climate likely played its part in this, humans may have been the main cause. A 2023 study published in Nature Communications weighs up the evidence, finding that it was most likely our ancestors who sealed the fate of the megafauna, particularly through human expansion. Long before written language had been invented, humans were already altering Earth's ecosystems across the globe.

[Featured image © 2008 Public Library of Science | Cropped and scaled | released as CC BY 2.5]

Abnormal extinctions

While the permanent loss of an entire species feels like an aching tragedy, small-scale extinctions happen all the time, even between global catastrophes. On its own, extinction is simply a part of the evolution of life on Earth, as organisms continue to change and adapt over time. Sometimes, the old must fall for the new to rise. Biologists call this a background extinction rate. Normally, every century, one in every 10,000 species on Earth dies out, never to return.

During a mass extinction event, however, this rate skyrockets. Vast numbers of plants and animals are lost at a dramatic pace. One past extinction was been estimated to span about 60,000 years — this may sound like a long time to us, but to the planet, it's barely any time at all. If the Holocene extinction began 11,700 years ago, it's likely only a fraction of the way through.

Extinction rates in the world today are currently far above the background level. Far, far above. One study published in Science estimated that the current extinction rate is around 1000 times the normal background level. Other estimates are even more severe, with some suggesting it may even be at 10,000 times the background. If you think this all sounds like cause for alarm, you're not alone. Scientists and concerned members of the public alike have been steadily calling for action to prevent things from getting even worse. Right now, at least, it still isn't too late to stop it.

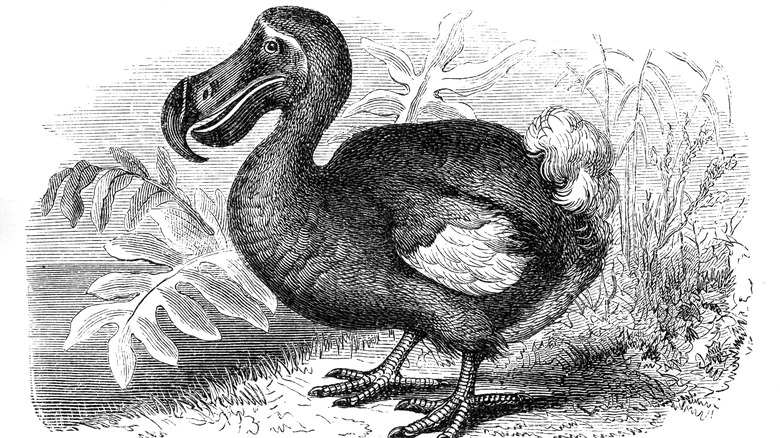

Dead as the dodo

It's no secret that humans have caused extinctions in the past, and the most famous example is the dodo. These flightless birds once roamed the island of Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean. When Europeans first arrived there, around the turn of the 17th century, the birds were an easy target for hunters; with no natural predators, they weren't used to fleeing from other creatures. Just 80 years after Dutch sailors reached Mauritius, the birds were no more, victims of a combination of overhunting and the destruction of their natural habitats. Being wiped off the face of the Earth in under a century, the dodo became an unfortunate icon of extinct species and a dire warning of how easily human expansion can exact a heavy toll on the natural world.

While the sad fate of the dodo bird is now seen as a cautionary tale about how easily entire species can be lost, there's an even more important lesson to be learned from this 17th-century tragedy. At the time, the dodo's loss was barely even recognized to have happened. As years stretched into decades, the dodo was mostly forgotten. For a while, before the 19th century, some European scientists even began to consider it a mythical creature. The story of the dodo, then, also highlights how easily humanity can barely notice the damage done to the world — a lesson that we all need to learn from right now.

The seventh mass extinction

The Holocene extinction is sometimes called the seventh mass extinction, although some still consider it to be the sixth. Regardless of the number, however, many scientists consider it an ongoing event with no signs of stopping without an intervention. Events like these can indiscriminately cut down species like wheat in a field. All kinds of animals, plants, fungi, and even microbes can fall victim, no matter how successful they were in the past. As one geologist at UC Riverside explained, in no uncertain terms, "Nothing is immune to extinction. We can see the impact of climate change on ecosystems and should note the devastating effects as we plan for the future." The effects aren't just limited to land either, with one study in Science noting some uncomfortable similarities between the condition of the oceans today and with those during previous mass extinctions.

While previous extinctions were caused by natural disasters, like volcanic eruptions and asteroid impacts, the Holocene is different. This time, it's entirely caused by human activity and the unsustainable way that much of modern society is maintained. As the human population on Earth increases, it becomes ever more urgent for us to address these issues, both for ourselves and for the world around us. Some experts think that Earth could potentially support billions more people than it does today, but only if we have the will to live more sustainably.

A lethal snowball effect

All life on Earth is deeply interconnected. Within its home ecosystem, every living thing plays a role. They depend on each other for survival, sometimes as food, sometimes as helpers, and sometimes to keep other species in check so their populations don't spiral out of control. One lost species impacts another, affecting another in turn, and so on. The whole thing ends up snowballing and can send things cascading into disarray.

Some species are more vulnerable than others. A study published in Science highlights that some of the most at risk are the apex species, sitting at the top of their food chains. Apex species tend to have longer lifespans, smaller populations, and slower birth rates. The result is that when their populations begin to fall, it takes much longer for them to recover. Elephants are a notable example of such a species. Elephant dung fertilizes soil and carries plant seeds far and wide, while the animals themselves dig the watering holes that a variety of animals rely on.

Other species have a much lower profile but play vital roles in their environments. The best-known of these are bees. Over 20,000 kinds of bees live on Earth, and the loss of even one can have terrible repercussions on an ecosystem as entire food webs are disrupted. Without bees to pollinate them, plant species would die off, cutting off food supplies that some animals depend on — to say nothing of the creatures that eat the bees themselves.

The trouble with humans

Again, the Holocene extinction is entirely caused by humanity's impact on planet Earth. Some wild animals have already been hit hard by this. About a quarter of bird species, for example, have already been lost. Rather than a single big cause, it's the effect of a cocktail of smaller ones, all tied to humanity's unsustainable practices. A major one is habitat destruction, including deforestation. Per the World Wildlife Fund, roughly 40% of all land on Earth is currently used for agriculture, and this is also the driving force behind 90% of deforestation globally. Agriculture also accounts for around 70% of the freshwater use in the world. All of this devastates environments as entire ecosystems are swept aside for farming.

This damage is further compounded by other factors like unsustainable hunting, pollution, and ongoing climate change. That last one is a significant one. Many species of both plants and animals can only live in the right climate. As the world warms, it puts stress on these species, and there's no guarantee they'll survive. This includes the plants being farmed. Experts have predicted that both coffee and chocolate could easily go extinct by the middle of the 21st century. Some of the damage done by climate change may already be irreversible too. As one study in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution notes, "some ecological niches lost due to anthropogenic climate change will never reappear."

The 21st century catastrophe

In the 21st century, the human activities driving the Holocene extinction have only increased. Over half of all anthropogenic CO₂ emissions have happened over the last three decades and, despite all the warnings, they are continuing to increase year by year. Many of the species this affects may not even be those most people notice. Insects and spiders, for example, are going extinct at a rate that experts have described as "alarming" (via BBC News).

As well as climate change, another serious problem revolves around money. Natural resources are exploited for economic gain, as big businesses continue to insist that their profits must increase each year. This ties in with another growing problem in the world — overconsumption. Simply put, Earth's resources are being consumed at a rate far faster than they can be replenished. The biggest responsibility for this lies squarely on the heads of the world's wealthiest people, who use up disproportionately more resources than anyone else. Some scientists and experts have even stated outright that the main problem is capitalism, with the consistent need for profits driving overconsumption, with a ruinous effect on Earth's biodiversity in the process. To quote a 2020 article published in Nature, capitalism is the direct cause of "enormous increases in inequality, financial instability, resource consumption and environmental pressures on vital earth support systems."

Disagreements and controversy

Science is, or at least should be, founded on disagreement and debate, pushing ideas and understanding to be constantly confirmed and improved. So it should be no surprise that not all scientists agree that the extinctions in the world qualify as a true mass extinction event. Their arguments are not unreasonable, either. The big one is that, even though the current extinction rate is dramatically above the background level, it may not be at the same level as previous mass extinctions in Earth's past. The main problem is the uncertainty. Not only is there uncertainty in the exact details of extinctions in the past, but no event has played out like this before.

There's a chance, however, that putting a label on what's happening in the world may be little more than a distraction. Even critics of the Holocene extinction have to agree that our planet is facing a biodiversity crisis. What isn't uncertain is that entire groups of animals are at risk. Amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, are particularly threatened, with two in every five species currently at risk. As well as factors directly caused by humans, climate change has side effects, like diseases that can ravage both plant and animal species. Amphibians have been experiencing a pandemic, as fungal infections burn their way through populations. Plants, including those grown as crops, may be at risk of a similar fate, as the changing climate allows diseases to spread more easily to new areas.

Extinction Rebellion

Whether or not what's happening in the world right now qualifies as a true mass extinction, the effects are becoming ever more noticeable on the world. The continuing loss of biodiversity is alarming enough that it's prompted protests around the world. Grassroots organizations like Extinction Rebellion have formed from people actively wanting to speak out and incite meaningful change for the better. Known as XR for short, one of this group's main aims is halting biodiversity loss.

Extinction Rebellion's methods have proven controversial, relying heavily on civil disobedience and inconveniencing authorities. While there's no denying that these tactics get attention, the group has since agreed to move away from their more disruptive forms of protest. All the same, the protestors have found support from a variety of high-profile figures, including scientists and certain government officials. As the newspaper Metro reported, judges have even allowed activists to walk free without charges after being arrested at protests, understanding the reasons behind their actions.

In this and other organizations, protests have been motivated by the experts repeatedly warning that drastic action is urgently needed to address biodiversity loss in the world and prevent further species from going extinct. To be effective, it isn't enough for individuals to act, and protests are focused on trying to spur governments into action. Without this, the effects of humanity's impact on nature could become catastrophic in just a few decades.

The Anthropocene

Humanity's effect on the world is undeniable, with over 8 billion people now living on Earth. The effects are so profound that some ecologists have seriously proposed a new name for this epoch of Earth's history — the Anthropocene, or the age of humans. The term hasn't been universally accepted yet and is still unofficial, but it's already been adopted by plenty of scientists. They argue, quite compellingly, that this epoch in the planet's history should be defined by the time when human activities began to significantly alter the environment, and with its many impacts on Earth's land, atmosphere, and oceans, this has certainly already happened. Currently, most consider the Anthropocene to have started around the mid-20th century. For simplicity, the year 1950 has been proposed as the official start.

Despite the name not yet being official, it's already begun to enter the zeitgeist. The phrase Anthropocene extinction (or, to appease the critics, Anthropocene defaunation) has already been used in news reports and published scientific papers. This comes with an uncomfortable realization, however. In Earth's geologic record, mass extinctions often mark the boundary between major time periods. If we aren't careful today, then the current extinction rate and biodiversity loss could become a defining aspect of any future discussion of the Anthropocene. We need to ask ourselves seriously if this is the legacy we want to leave behind in our planet's permanent record. We can still change this if we have the will to do so.

Earth's uncertain future

The mass extinction events in Earth's past, perhaps counterintuitively, have been responsible for a surprisingly small percentage of the total number of extinct species. Make no mistake though, their effects have been profound. Each time, of course, the world has recovered, but it's a slow and arduous process. In many ways, the recovered Earth found itself as an entirely different planet from the one that came before. What exactly that could mean by the end of the Holocene extinction is impossible to tell.

Extinction events take a long time, at least on human timescales, but the recovery process takes far, far longer. According to one study at University College London, fossil records show that it takes Earth's ecosystems around 2 million years to recover after an extinction event. This varies dramatically from ecosystem to ecosystem, though, with some taking even longer. After Earth's largest-ever extinction, it took coral reefs 14 million years to fully recover.

Mass extinctions do leave behind plenty of unoccupied ecological niches for new organisms to reclaim and occupy. With so much left behind, living things are free to either develop new specializations or even learn entirely new survival strategies. Unfortunately, evolution is not a fast process. Can the world recover from the Holocene extinction? Yes, very likely. But what that future Earth will look like is anyone's guess. In the meantime, humanity may easily find itself living on a very lonely planet.