What Life Was Really Like For Families During The Great Depression

Over the course of a few short weeks in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression rocked the United States. Banks went under, and patrons lost all the money they had earned. As businesses failed and workers lost their jobs and livelihoods, people were forced to try to find any work they could to support their families, feed their children, and keep a roof over their heads. For some, the task was impossible: Many Americans became homeless, living on the road or in ramshackle tent cities known as Hoovervilles. All around the country, people were struggling.

Lots of couples chose not to start families, waiting to get married and have children until there were jobs available and the world felt more stable. Some fathers abandoned their families, leaving their wives to care for their children alone. Countless teens and children were left to fend for themselves. Despite the hardships, however, many families stayed together and worked to find ways to survive. Here's what life was really like for them.

Families lost their homes

When the Great Depression was at its worst, around 12,830,000 in the United States were unemployed, and others lost their livelihoods. For a lot of families, their lives turned upside down immediately when their primary providers stopped being able to afford to keep a roof over their heads.

In an interview (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting), John Hope Franklin recounted how his family losing their home during the Great Depression caused him to have a lifelong fear of homelessness. Franklin's father was a popular Black lawyer in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he catered to Black clients, but when the Depression devastated their community, his clients were unable to pay their legal fees, and the Franklin family lost their home. Franklin explained, "It is impossible for me to tell you what a remarkable impact that had on me, in the way, in a manner of depressing me and of disappointing me, and of feeling really homeless."

While the Franklin family was able to survive by moving into a small apartment, other families were forced to live on the streets. Tent cities known as Hoovervilles sprung up around the country, which sometimes had thousands of people living in them at a time. There, people who had lost their homes had to build whatever kind of shelters they could to keep their families safe, sometimes using nothing more than cardboard.

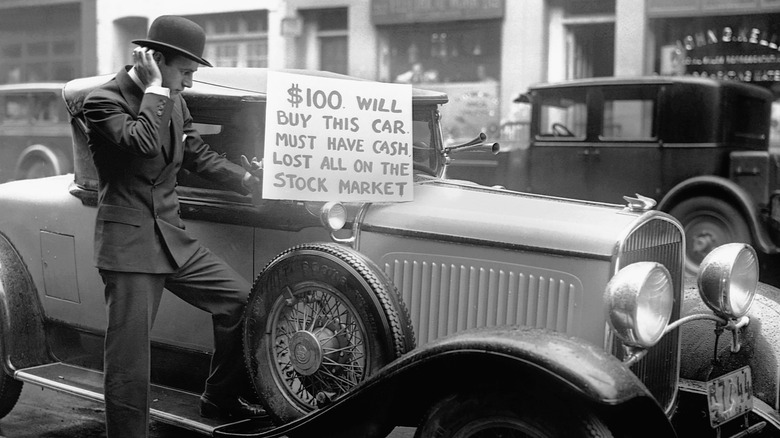

Most people walked everywhere

Although cars had been popular in the 1920s, almost nobody could afford to buy one during the Great Depression. During that period, if you wanted to get somewhere, you usually had to walk, which could mean that your life was limited to places within walking distance. As described in an interview from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis with Anna Maria McIntyre, whose family grew up in the city during the Great Depression, "We only knew one person that had a car. I remember we lived within a five-mile area basically our whole young life."

Some urban areas did offer one alternative to walking: trolleys. People who could find work requiring them to get around the city often had to purchase a weekly streetcar pass, which offered unlimited rides for 50¢, the modern equivalent of around $12. That price was still too expensive for a lot of people, so sometimes one passenger would secretly drop their pass out the window of the trolley for their friends to use, meaning that only one person actually had to pay to ride, and the others could get on for free.

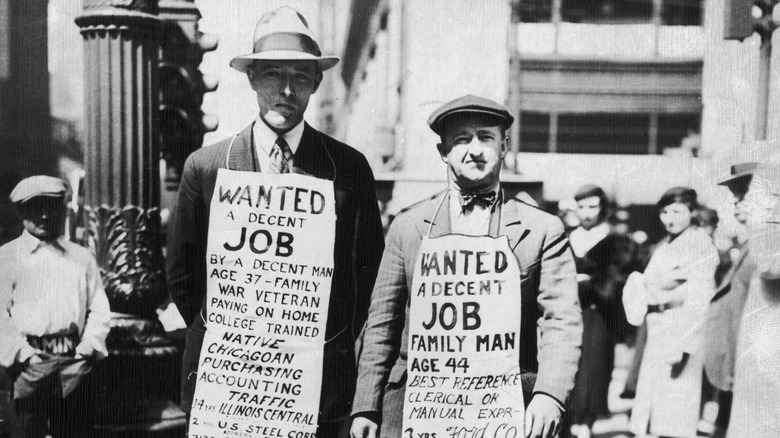

Everyone had to take whatever work they could get

With work being so scarce, those living through the Great Depression were forced to take whatever work they could get to feed their families. For some, that meant waiting hours in unemployment lines in hopes of getting work for the day, even if it was something they were overqualified and underpaid for. For others, it meant traveling around the country alone, looking for any kind of paying work that would allow them to send something home to their children.

It wasn't only husbands and fathers who had to do everything they could to find a job. Women and children also had to look for work if they wanted their families to survive. During this period, working white women tended to work in nursing and teaching, while working women of color worked in domestic jobs. In general, the jobs that women could get both before and during the Great Depression paid significantly worse than the jobs available to men – but they also were less likely to lose their jobs because of the economic crash.

As New Deal programs went into effect, some of the most effective regulations on child labor in American history were implemented – but that didn't mean that children weren't working to support their families. As detailed in an article from The University of Richmond, on struggling farms children were expected to work long, hard hours, and in urban areas many had to leave school and find odd jobs to help make ends meet.

Living on a farm could be a mixed blessing

In some ways, families that lived on rural farms were better equipped to deal with the hardships of the Great Depression because they were able to grow their own food. In an interview from the Omaha Folklore Project, Stanley Dygas described how his family was spared some of the worst because of his parents' decision to be farmers. "After a while we found out that we had more freedom, we could go places, we could go treasure hunting, we could do things that we never'd thought possible ... city folks had it harder than we did because there was no work in the city either."

Not all farmers were as lucky as the Dygases. As people around the country were unable to pay for anything but the cheapest food, some farmers lost their incomes. Many would also lose their land, animals, and homes, leaving them just as desperate as city workers. A lot of people who had been farmers, particularly Mexican American farmers, were forced to become migrant workers, leaving their families behind and looking for any farm work they could get.

Christmas wasn't necessarily canceled

While almost no one could afford to splurge during the Great Depression, many families were still able to make the holidays fun for their families. Those who could still afford to put up a Christmas tree often decorated it with glass balls, foil garlands, and metal icicles. Unfortunately, a lot of ornaments at the time were manufactured using lead, which put children at risk of lead poisoning. Trees were often decorated with electric Christmas lights, with elaborate nativities and model Christmas villages made of cardboard around them.

Some communities hosted Christmas parties for the people who lived there. As described by Anna Maria McIntyre (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting), in 1934, the mayor of St. Louis hosted a party that her whole family attended. "We had a wonderful time. I still have the gift I received ... a little set, believe it or not, of living room furniture. "

Miniature furniture was not the only gift you might receive during the Great Depression. One of the most popular gifts was the new board game Monopoly. For the first time, many presents were wrapped up in brightly colored paper, like they would be today, as Scotch tape, gold ribbon, cellophane, and patterned wrapping paper all became widely available during this era.

The whole family would listen to the radio

During the Great Depression, most people could not afford to go out and have fun in the ways that had been popular before the economic crash, but one thing that they could still enjoy was listening to the radio. As described in an interview from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis with Margaret Barrett, who lived in a rural farming community at that time, there were a lot of different programs that the whole family could gather around and listen to together, from comedies like "Amos 'n' Andy" to "Fibber McGee and Molly" and Kate Smith's tremendously popular music. There were also sports on the radio: Raymond McIntyre described how his family used to gather around the radio on Friday nights to listen to boxing matches (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting).

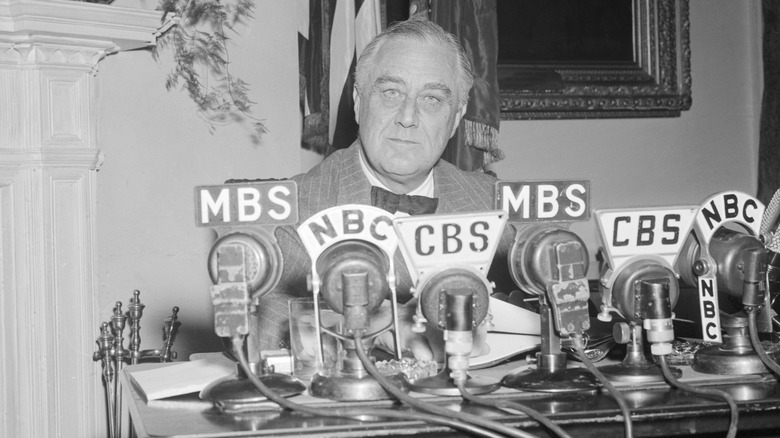

The most famous Great Depression-era radio broadcasts were certainly President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Fireside Chats," during which he addressed the nation 31 times between 1933 and 1944. Sam Weber, who grew up during that period, described (via the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) how listening to Roosevelt made him feel, saying, "He gave you a lot of hope. He visualized better things all the time. He always buoyed you up. Those were some good chats, and people would look forward to hearing him."

The community might help you out, but it wasn't a guarantee

Some of the most heartwarming stories to come out of the era are about neighbors helping each other through the hard times. In an interview from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Margaret Barrett described how the family that lived next door was in dire straits because their father had lost his job, so Barrett's father allowed him to hunt for game to feed the family on his land, and went out of his way to hire the sons to work on his farm. She also described how her mother would feed anyone who came to their door in exchange for help with the chores, saying, "She would make sandwiches or whatever we were having ... she always asked them to chop wood out while she fixed their dinner and their lunch ... that happened quite often during the Depression."

However, not everyone was as supportive of their neighbors as Barrett's parents. In an interview from the Omaha Folklore Project, Stanley Dygas described how people were unwilling to help his family when they were in need because his parents had come from Austria-Hungary and spoke Polish and German. "Once they learned that you were a foreigner, your parents came from a foreign country, you were a minority ... You had to fight for your rights."

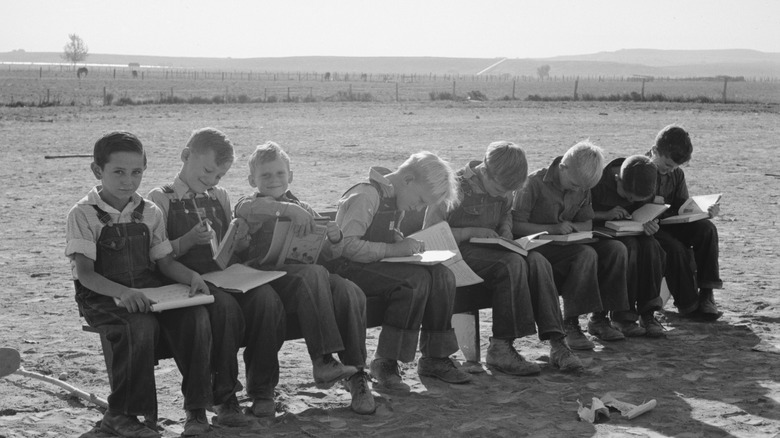

Some children still went to school

Some families were forced to pull their children out of school, but some were able to keep attending classes. Exactly what that was like depended on who you were and where you lived. If you lived in a rural area, you might have had to travel a long distance or even stay with relatives to attend. In an interview from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Margaret Barrett, who went to a Catholic school, stated, "There were only about 50 children in the high school. But the grade school had about 160. So most of the children who lived on farms did not get to go to high school. And some who started out, only went two years."

In an interview with acclaimed poet Maya Angelou (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting), she described her time at Lafayette County Training School, which was segregated and attended only by Black students. Angelou loved to read, and her teacher encouraged her to read every book that their school had, and when she had finished them all, brought her some books from a nearby school for white students. It was only then that Angelou realized how much less her own school had.

"I had never seen a new book until Mrs. Flowers brought books from the white school for me to read," Angelou recalled. "The slick pages, I couldn't believe it, and that's when I think my first anger, real anger at the depressive and the oppressive system began."

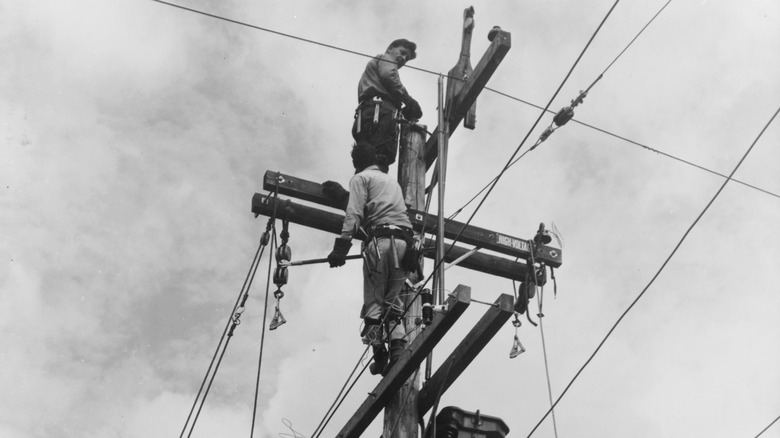

You probably had electricity in your home

"It was '37 when Roosevelt had the electric lines put through, the rural electric lines, and we had our first electricity in 1937," as Doris Richardson-Findley, who lived in rural Indiana during the Great Depression, explained in an interview recorded by the Omaha Folklore Project. "That was really something wonderful."

Richardson-Findley wasn't the only one. Starting in 1935, the Rural Electrification Administration began its mission to bring electricity to America's farming communities in an attempt to revitalize the economy and create jobs. By 1939, a quarter of all farms had electricity, and that number only continued to grow. Electricity made the lives of farmers significantly easier in most cases, but for some, it took a little getting used to. In an interview from the Southern Oral History Program with Lena Boyce, who lived on a farm in North Carolina, she admitted how shocked she was to see what her home looked like the first time the electric lights turned on. "I won't ever forget that ... My kitchen walls looked so dirty! I just couldn't believe it. The lights were so bright ... during the day we had sunshine and all that, but yet it didn't come in the house like the electric light did."

You might be forced to waste what little you had

During the Great Depression, people could get so desperate that they were forced to sell or use everything they had to survive, even if it meant taking a significant loss on it. This was especially true of people who lived on farms, who sold whatever they had grown at whatever price they could get for it to pay their expenses. Even though they often had enough to eat because they grew their own food, farming families still had to have enough money to pay their taxes and to afford fuel, especially in the winter.

As described in an Omaha Folklore Project interview with Doris Richardson-Findley, who lived on a farm in rural Indiana during the Great Depression, her family could not afford coal, so they were forced to burn their corn crop so that their four children wouldn't freeze. They weren't the only ones. "All the neighbors would know you were burning corn," Richardson-Findley recalled. "Because it has the smell of roasted corn."

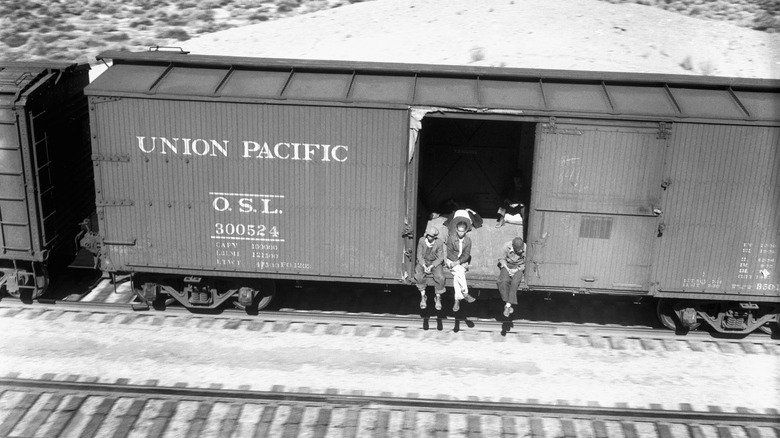

People lived on the road

When picturing the Great Depression, people may think of migrant workers "riding the rails" by secretly sneaking onto freight cars that would carry them to what they hoped was a better life with more opportunities. This was a real phenomenon, in which unemployed Americans traveled the country, taking up any work that they could get. Some, known as troubadours, traveled from town to town trying to make money by playing music. As described by poet Maya Angelou (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting), "Their instruments sometimes were wash tubs, and sticks in them, and cat gut. So they had wash tub bases ... They had cigar box guitars, literally, cigar boxes with the fret made of a piece of wood and cat gut strung."

Thousands of those migrant workers were teenagers. As noted by PBS, more than 250,000 teens were unhoused during this era, and many traveled around the country in search of work. Some were able to find odd jobs, but others had to steal or beg to survive. It was a dangerous life. In addition to the physical risks of living on the street, many were constantly on the run from police and were often arrested and put in jail. In some places, local communities turned on the migrant workers who came to their towns and would attack them or try to force them out.

For some people, life was already hard

The Great Depression destroyed the lives of countless families around the United States. For some, however, their lives were difficult long before the economic crash – in some cases so difficult that one of the greatest disasters in American history barely made an impression on them. As described in an interview from the American Archive of Public Broadcasting with Togo Tanaka, an Asian-American who was in college during the Great Depression, "It was always hard times for our family, so it didn't make too much difference. We owned a fruit and vegetable stand, so we had enough to eat ... I don't recall it being any harder or easier."

In an interview (via the American Archive of Public Broadcasting), Maya Angelou stated that the Depression couldn't make life much harder for the Black community, either, particularly those living in the rural South. "There's a bitter and yet rye statement which was made by blacks about the Depression. They said in the south that the Depression had been going on for ten years before black people even knew about it, even knew it existed ... people lived subsistence."

Black Americans were often asked for help by the unemployed people who were suddenly displaced and traveling the country looking for work, many of whom were white. According to Angelou, Black communities were notable for their willingness to help out and feed hungry travelers, so a lot of migrants sought out Black neighborhoods first whenever they came to a new area.