How WWI Changed London Forever

It's hardly an overstatement to say that World War I was a huge event in history, one that brought with it plenty of change and set the stage for the conflicts that occurred throughout the rest of the 20th century. After all, just about anyone you talk to knows about World War I, even if only in the most vague of terms.

But despite the war's massive impact on international affairs for years to come, it also had much more local effects. Sure, there's plenty to be said about how it affected the world order to the point that it might have helped to cause World War II, or even in how it was something of a first step toward the eventual founding of the United Nations. But the war also affected the politics, culture, and social pressures within the individual nations that took part.

And when it comes to England in particular? Well, both public and political responses to the conflict led to several changes — some positive and some negative — that would affect the country for years, long after the armistice was signed and the terms of peace were fully negotiated and agreed upon. London itself was a center of change, where the effects of the war could be seen far and wide.

Damage to the German population

German immigrants have a long history in the United Kingdom; not only that, throughout the 19th century, the German community was the largest foreign group in the country. All told, it would be pretty hard to disregard the Germanic influence throughout London, as well as the huge number of immigrants.

But the outbreak of World War I (and the sinking of the Lusitania) changed that, with those of German descent — even those born and raised in the U.K. — suddenly becoming the enemy. Violence broke out across London, with looters breaking into German-owned businesses and rioters even following families into their own homes just to toss them into the street where they could be attacked.

The German population was largely shunned from all public life or forced to hide their identity for their own safety. In most cases, though, many of those affected just chose to leave the country, and the numbers are proof enough. Per the journal Cahiers Bruxellois, the German population of London prior to World War I numbered well over 30,000; in 1921, that number had dropped to less than 10,000. What's more, Austrian immigrants weren't safe from the same sort of vilification, even if on a slightly smaller scale. The community of nearly 9,000 Austrians in London pre-World War I dropped to just over 1,500 by the war's end.

A new name was heard on the streets

Once World War I broke out, there was a pretty decidedly negative view growing toward German communities — something that might almost make sense, given England and Germany were enemies in the conflict. But that view ended up getting a lot of innocent people caught in the crossfire, including the British royal family.

See, the royals weren't always known by the name that they are now, largely because European royalty is a bit complicated, to put things lightly. Speaking very generally, there are quite a few ties between the royal families of many different nations; King George V was even cousins with the infamous Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. More relevant, though? The British royal family had very close — and very explicit — ties to German nobility. Kaiser Wilhelm II was also King George's cousin, for one, and the British queen was German by birth. Titles claimed by those of the royal family were German, tying them to Teck and Battenberg, for example. And even more telling was the family name: Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

The final straw came with a particular raid in which a school was destroyed and children were killed, the bombs having been dropped by Gotha bombers. After that, King George thought it best to distance the family as far as possible from its German ties. In June 1917, all German titles were abolished or changed, and the family's name was changed into something easily recognizable to 21st-century Londoners: Windsor.

Blissful ignorance of civilian internment

When you think about the wrongful internment of innocent civilians, there's a good chance that you'd think of the death camps of the Holocaust. Or maybe you'd think of another example contemporary to that: the Japanese internment camps run in the United States. But the U.K. beat both the U.S. and Germany when it came to civilian internment; the only thing is that most British history has chosen to largely ignore this particular injustice, leaving most people in the dark as to what really happened.

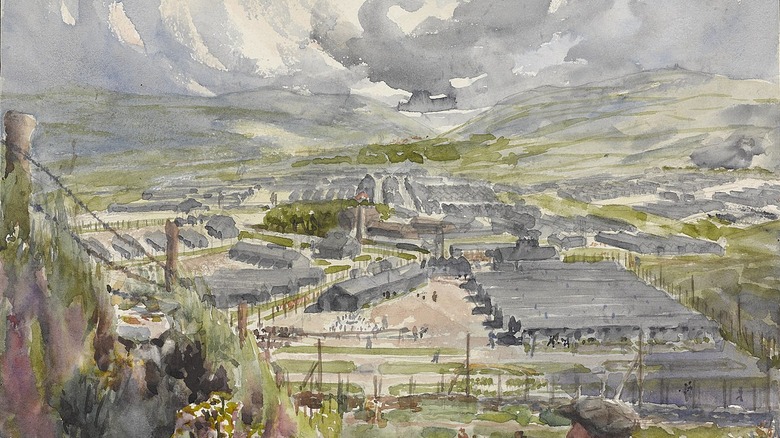

Anti-German sentiment was generally on the rise, but on top of that, Germany had actually proposed that those of German descent (including those abroad) return and join the army. The British government began to fear that even its own citizens would genuinely become the enemy, and so their answer? Internment. Over a dozen camps were set up around the country, with one of the largest holding some 20,000 people. London itself was home to one such camp — Lofthouse Park — in which about 1,500 people were interned, despite not being guilty of any crimes.

The camp burned down only a few years later in 1922, and that only helped to sell the narrative that most British citizens wanted to believe going forward: the vision of World War I as a just conflict, in which England was fighting the good fight, so to speak. The establishment of internment camps doesn't quite fit that image, and so it's become something of a blind spot in the eyes of British history.

Massive changes to the economy

If you take a look throughout world history, then there's a good chance you've heard something about colonialism and the British Empire. While that's an entire topic in and of itself, it suffices to say that England successfully maintained a place as one of the most powerful countries in the world for a rather long time. And that's not just in terms of land ownership but also in terms of wealth and economic power.

However, the start of World War I changed a lot of that. Comparatively, England was no longer the singular military superpower of the globe, and with conflict came the need for technological development. But with development also came cost — in other words, defense spending. In turn, the government had to find a way to fund the war effort, which came in several forms, from taxes to wartime bonds to borrowing from foreign governments. Graphs of any financial activities from the period tend to look very similar to each other; defense spending, revenue gained from taxes, and the national debt all rose sharply in the first few years of the war.

What's more, if you look at the following years, most of those numbers remained rather large, rarely returning to their pre-war levels. The national debt, for example, stood under £1 billion before the war, rising to over £7 billion by 1919. And, for further reference, the national debt as of June 2023? Over £2 trillion.

Increased rights for women

All around England, World War I meant huge changes for women. With men off to fight on the front, women were finding new careers for themselves: munitions, transportation, law enforcement, and auxiliary aid for the armed forces. None of these jobs were easy (or safe), and the entrance of even more women into the workforce brought many of them to begin fighting for equal rights, bringing women's rights and gender norms more generally into the spotlight.

During the war, the question of childcare for working mothers was addressed, at least to some degree, and some women began to strike for equal pay. The same sentiments continued after the war's end, when capable women were suddenly forced into unemployment or domestic spaces. Calls for equal pay and employment — as well as sexual freedom and women's liberation more generally — could be heard across the country.

On some levels, those calls were answered; for example, in 1918, women were finally given the right to vote, and in the next few years, women could join both the legal and political landscape. That said, it should be noted that none of these advances came without complications. Suffrage is an interesting example: While some women could vote in 1918, that wouldn't be true for all women for another decade. Beyond that, not all women actually agreed on what gender equality meant, and as time went on, the question of women's rights (as well as their contributions to the war effort) began to fade from the public's memory.

A shift in industrial power

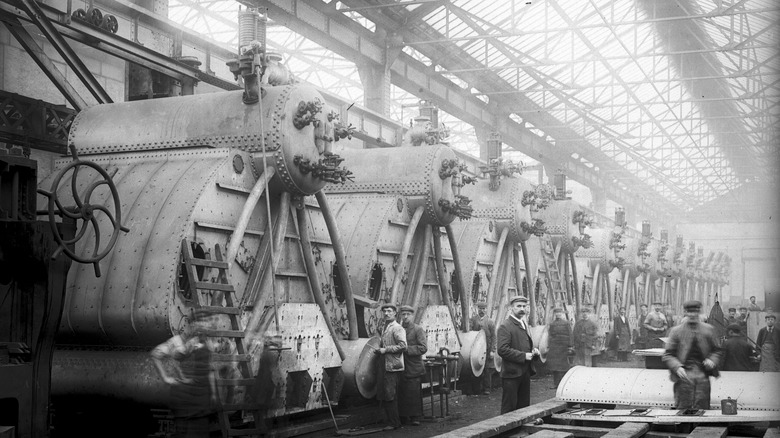

Prior to World War I, areas in the western half of London were fairly undeveloped, to put it lightly. Despite London being a huge city and something of an economic powerhouse, areas like Wembley and Acton had little to show in the first decade of the 20th century. There were only a dozen factories dotting the landscape, and one of the most notable events was a failed attempt to build a permanent showground (called Park Royal) for the Royal Agricultural Society. Not exactly an impressive resume.

But World War I changed all of that. Railways had been installed in the decade prior, allowing for easy transportation of materials, and all the unused land was leased out to the army to use for munitions manufacturing. Around the same time, local businesses gained national acclaim; the biscuit company McVitie's worked with the government to provide rations to soldiers. More farms started to crop up, and thousands of workers found new jobs in the wartime factories.

Though things slowed down for a bit when the war came to a close, new entrepreneurs moved into the old buildings and continued to develop the area, to the point that, by the early 1930s, there were about 70 factories and twice as many businesses. The trend only persisted from there, and industrial and economic power generally shifted to the western parts of London.

The evolution of the English language

Given enough time, every language ends up evolving; that's nothing new. The popularity of new terms rise and fall over time, catalyzed by contemporary social norms, and in that sense, the arrival of new slang on the streets of London after World War I isn't that surprising.

However, the reason those slang terms gained popular usage is pretty interesting. During the war, the British government instituted conscription, meaning everyday folk were suddenly experiencing military life. The lines between the two groups — civilians and military personnel — blurred to nothing, and terminology used by soldiers passed into everyday life. And it wasn't just slang created during World War I (many of which were anglicized versions of French words) that became popular; even military slang from decades earlier found its way into civilian life.

Of course, plenty of those terms fell out of favor eventually; most modern-day Brits wouldn't recognize "no bon" ("no good"). But that's not the case for all slang brought home from the front. "Tooter the sweeter," for example ("the sooner the better," for those less familiar with British turns of phrase), comes from that time. Then there's "Blighty" — a word still used today as another term for Britain and coined by the British military by borrowing from Urdu. The term came about in the 19th century but didn't enter widespread usage until World War I. Beyond that, there are the terms that have lasted in both British and American slang: "No man's land," "cushy," and "whizz-bang," to name a few.

Morale in the face of danger

When it comes to instances of civilian populations of London being bombed by enemy aircraft, the Blitz of World War II probably comes to mind: civilians hiding in bunkers, weeks on end of nighttime bombings, and the like. However, London was also bombed in World War I, and it informed the government in the following years.

During World War I, the British government had no idea how to defend its people from the random air raids, which killed hundreds in the first years of the war. There was no warning system, nor any means of defending the city. Eventually, people developed strategies to keep themselves somewhat safe — turning off lights or hiding in the London Underground — though fear and anxiety were common. Ultimately, the government formed official committees and services specifically for the protection of the people in the case of air raids; those services would prove to be invaluable during the Blitz.

But the effect of air raids goes beyond that. They were always meant to harm the morale of the people, and government officials have continued to keep that in mind to this day. They've retained the goal of keeping morale high in the face of disaster but also do so by assuming that panic is a very real possibility. In practice, that means taking precautions whenever possible, advising that people stay informed. It worked in the midst of war, and the assumption is that it will continue to work in the modern world with its new threats, such as terrorism.

The founding of the BBC

For all the damage wrought by major wars, there are also plenty of examples of those same wars bringing about major technological advances. In the case of World War I, one of the most influential technologies to come from the front was radio. Granted, radio had been around prior to World War I, but it revolutionized tactics on both sides of the war. Soldiers could be warned of imminent threats quickly and accurately, and communication between troops in airplanes and on the ground was possible.

After the war, though, radio became an interesting novelty. Those who had worked with radio equipment during the war continued to, experimenting with how far they could broadcast messages. Those messages eventually came to include music and entertainment of many varieties, and that essentially gave birth to the concept of radio as it's known today. The first public radio broadcasts came in 1920, put out by several different companies. Over the next couple years, they decided to merge, becoming a news service that you're likely familiar with: the British Broadcasting Company, or the BBC. In 1922, the BBC officially started its first national radio service, calling from none other than the British capital city.

The popularity of radio was a bit underwhelming at first, but by the late 1930s, millions of people in England were tuning into radio stations for both news and entertainment. And the success of the BBC (still headquartered in London) hardly needs to be stated.

England's Lost Generation

Generally speaking, the end of the war brought along a disillusionment with pre-war values; in the U.S., that was most obvious in the works of Lost Generation writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald or Ernest Hemingway. But London had its own "Lost Generation," so to speak, and they were often referred to as "Bright Young Things."

In general, these were young socialites and artists coming of age in the wake of war. Their parents' values meant little, and they felt they didn't have any of the assurances for the future that older generations had enjoyed. As a result, they decided to live their lives to the fullest, enjoying the moment: lavish parties marked by drugs, drink, and dancing, spectacular games and treasure hunts across the city, but also greater acceptance in terms of sexual identity and gender expression. With all of that came plenty of scandal, however, as members of the Bright Young Things became regular subjects in tabloids. Then, there was also the darker aspect of the entire movement: These were people who burned bright and fast, leaving behind legends of their exploits, but little beyond that.

By the time of World War II, the movement had largely died out, but it arguably birthed a phenomenon that's very familiar in the modern day: the cult of celebrity. These were people for tabloids to obsess over, people who could use those same news outlets to further foster their own status. They were people who were famous simply for being famous — not an unfamiliar concept in today's society.