The Painting That Popularized The 'Doomed Poet' Trope

Just over 250 years ago, a teenager died alone in a squalid garret room in the poverty-stricken district of Holborn, London. Just 17 years old, the boy had taken a dose of arsenic. Rumor would later spread that he had died by suicide. He was Thomas Chatterton, a poet born in the English city of Bristol in 1752 who had traveled to the capital to seek literary fame and fortune. These evaded him in life, but in death, Chatterton became one of the most celebrated writers of the 18th century, whose plays and verse would later attract generations of admirers and influence some of the greatest poets of the next two centuries.

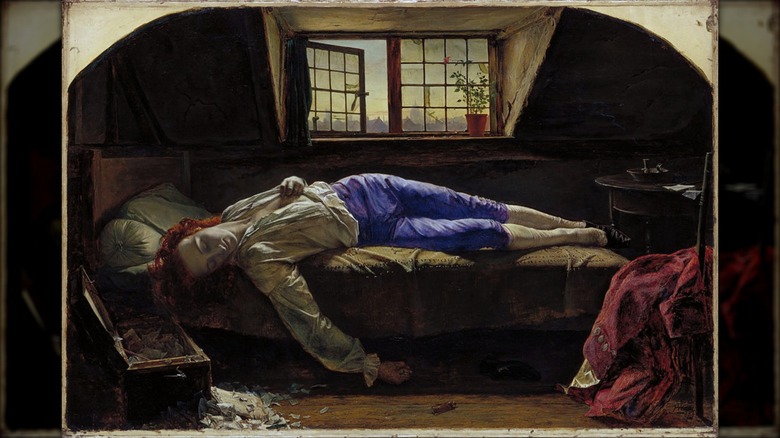

Chatterton wasn't the only English poet to die young in tragic circumstances — in 1821, John Keats died of tuberculosis at the age of 25, while 29-year-old Percy Bysshe Shelly drowned off the coast of Italy the following year. Lord Byron, one of the most famous people of his age, died of an illness while fighting in the War of Greek Independence in 1824 at the age of just 36. But Chatterton became established as the paradigmatic figure of the doomed poet throughout the 19th century and beyond. Much of this has to do with his influence on the poets who came after him. But for the wider public, Chatterton's legend was cemented by a painting by the artist Henry Wallis, which stunned gallery-goers on its first public displays in 1856 and implanted the idea of poets as tragic figures in the public consciousness.

Burning ambition

Though Thomas Chatterton was to be hailed as a genius by some of the greatest poets who ever lived, his early life was troubled. The legend goes that as a child Chatterton was a poor learner, who for many years was unable to read at the level expected of him. However, at the age of 6 the boy, who was also a painfully shy daydreamer, became enraptured by the sight of illuminated parchments — books that had been painted by hand in full color — which his mother was tearing up and using for fuel to light the fire.

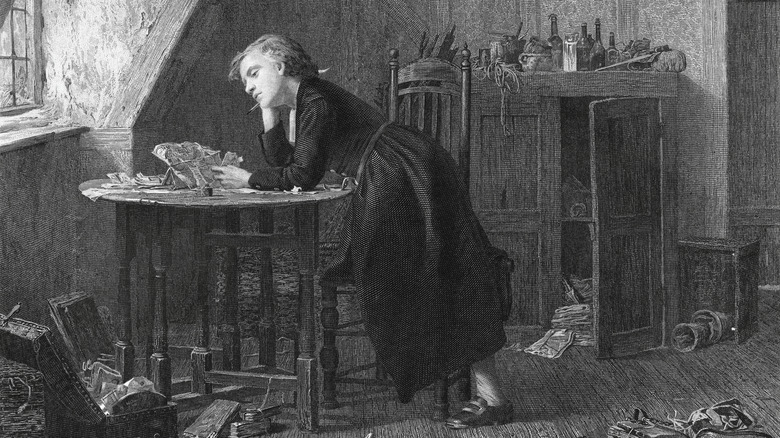

Chatterton thereafter became a voracious reader, who absorbed the greatest works of literature in the English language alone in the attic of the Chatterton family home. Though he was orphaned by the age of 8, at 10 he was already producing poetry of amazing quality, and published works in magazines and periodicals that established him as a prodigious talent. However, he labored under various pressures, including a day job as an apprentice attorney, which he loathed so much that he wrote his employer a mock last will and testament in which he claimed he would die by suicide if he was not released from his contract. His employer took him at his world, and Chatterton set off to London to make the acquaintance of editors and publishers.

Chatterton met his ruin in London

Tragically, Thomas Chatterton's life in London failed to turn out as he had hoped. In the 18th century, English poets didn't tend to make money from mass sales to a large readership. Instead, they gained the freedom to practice their art in a state of financial security thanks to stipends given to them by one or two exceptionally wealthy patrons, usually aristocrats. Though Chatterton wrote prolifically and published widely, the would-be patron he attempted to court died before the poet was able to establish himself. To complicate matters further, Chatterton had alienated himself from a portion of the London literary scene with a series of poems that he claimed were historical documents attributed to a 15th-century monk named Thomas Rowley, but which many including the writer and critic Horace Walpole believed were forgeries.

With spiraling debt as a result of a rent increase imposed upon him by his antagonistic landlady and frustrated by the failure of his poetry to establish him as a legendary writer in his short lifetime, the starving Chatterton is said to have died on the night of August 24, 1770, after reportedly imbibing opium — a commonly available drug at the time — and arsenic, which contemporary reports claimed he had consumed in his garret room in a fit of madness.

Henry Wallis made Chatterton a star

Criticism from the early part of the 20th century is effusive in its praise of Thomas Chatterton, whose influence is said to have revolutionized the stilted art of poetry and laid the groundwork for verse as it is known today. Writing in the Mark Twain Quarterly in the late 1930s, Charles Edward Russell claimed that Chatterton reinvigorated poetry with a new sense of melody, leading the way for such master poets as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Edgar Allen Poe, and Alfred Lord Tennyson. For many poets down the ages, Chatterton's period pieces under the name Thomas Rowley — which were definitively proven to be by Chatteton's hand in 1778 — stand as his highest achievement.

According to the book "Deaths of the Poets," by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, Chatteron's tragic story truly broke into the public imagination after the up-and-coming painter Henry Willis chose Chatterton as the subject for his first publicly displayed work. "Chatterton," more commonly known as "The Death of Chatterton," strikingly portrays the dying poet in his final moments as a Christ-like figure. Around him are symbols of his wasted talent: a snuffed-out candle, a wilting rose, and a case of shredded poems. The painting caused a stir when it toured the galleries of Britain, especially in Manchester in 1857, where an estimated 1.3 million visitors, many of whom were new to the art of painting. "Chatterton" and its various copies created a new stereotype that would prove timeless and irreversibly create in the public's imagination an association between poets and tragic death, and the idea that artists martyr themselves for their art.

What was Thomas Chatterton's real cause of death?

As the Tate Gallery explains in its notes on Henry Wallis' "Death of Chatterton," the painting was Wallis' first to be exhibited. Though it made the artist's name, he never produced another work as popular or timeless. The Chatterton painting contained many romantic and symbolic elements and the work that Wallis created immediately after concerned the plight of manual workers in Britain, leading some experts to believe that rather than a heroic image, it may be considered a social critique of a country that lets even its more promising artistic talents descend into poverty and suicide.

However, even in the years immediately following Chatterton's death some doubted that despair had driven him to take an overdose of arsenic. Some scholars have pointed to Chatterton's many flirtatious letters to women sent during his time in London as evidence that the poet indulged in a full and hedonistic romantic life in his final months and that it was likely he had contracted venereal disease, which was rife in the capital at the time. It has been suggested that Chatterton may have died accidentally as a result of drugs he may have been taking to combat his symptoms.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org