The Untold Truth Of The Army's Intelligence Support Activity

When you think about the world of espionage — super secret spies risking their lives to gather valuable intel — you might start thinking of the CIA. In a lot of ways, that's not necessarily inaccurate, but there's actually a government agency that fits the bill even better. And, very fittingly, there's probably a pretty good chance that you've never even heard of it.

That group is the Intelligence Support Activity, or ISA for short, and it just might take the cake for being one of the most secretive government organizations in the United States. The group was founded in 1980 and has quite the list of impressive achievements under its belt, from taking down foreign dictators to perfecting the art of covert intelligence gathering. The latter in particular is what the ISA is known for, as they often provide information to operations carried out by other military groups. That said, intelligence isn't the only thing that the ISA excels at, and by design, their exact responsibilities change as necessary, taking on dangerous tasks that other agencies aren't willing to risk.

Being a highly secretive organization, there isn't a whole lot that's widely known about the ISA, and the details of their exploits aren't exactly common knowledge. Regardless, there are bits of information that have managed to seep out over the years.

Intelligence Support Activity is far from the only name for the group

If you've never heard of the Intelligence Support Activity, well, there's a good reason for that. Even among the U.S. Special Forces, there's a good argument to be had that it's the most secretive of all of those enigmatic groups (which includes wider-known organizations such as the Navy SEALs, along with mysterious ones like Delta Force or SEAL Team 6). There's very little information floating around, and anything the public has managed to hear? Well, it's undoubtedly outdated.

Part of that secrecy likely comes from the fact that you might have heard about the ISA without ever realizing it; the group has operated under many different names over the years. It even formed under a different name — the Field Operations Group – and has since been called plenty of other things: Task Force Orange, the Army of Northern Virginia, and a fair few other titles for specific operations, like Gray Fox or Quiet Enable.

It goes even further than that, though. If, hypothetically, you could get your hands on confidential government documents, you wouldn't even find the name "Intelligence Support Activity" anywhere. A memo from March 1989 banned the use of the name — including all of its acronyms, like "ISA" or "USAISA" — from any official correspondence. The name you'd see in its place currently is anyone's guess, though. Talk about secrecy, right?

The ISA's existence broke Congressional law

As it turns out, referring to the ISA as a secretive organization goes far beyond the way it might be perceived by the public. After all, keeping the common folk in the dark is one thing, but even government officials (and other government agencies) were often kept out of the loop when it came to the ISA.

For the first few years of its existence, the ISA was operating without any sort of authorization from Congress; beyond that, the Pentagon itself had neglected to ever mention the ISA's existence to Congress. It was no stretch to say that almost no one knew what the ISA was truly doing, with even the CIA being largely unable to answer any questions about the group. While that could've been due to a need to maintain confidentiality, there's also reason to believe that wasn't the case. In other words, the CIA just didn't know what was happening. Pretty crazy, right?

Of course, all of this was intentionally done. The name of the group (and its initials) had been kept out of any official documentation for a long time, specifically to make sure word of its existence didn't make it to Congress. And this was more than simply keeping the name out of conversations. Rather, if it was mentioned in recorded conversations, audio would be edited and cut, just to ensure that information didn't make it beyond those who needed to know.

The group sought to improve on foreign models

There's no arguing that the ISA is a decidedly American organization, working toward American interests across the world. On top of that, there's a long history of covert intelligence gathering being a part of military operations in the U.S. — it even goes back to the American Revolution, interestingly enough. Despite that, the ISA took its inspiration from foreign groups, rather than domestic ones.

More specifically, the founder of the ISA, Jerry King, had experience working with British special forces units — the Special Air Service (SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS). These two British groups had been active for quite some time, tracing their roots back to the early 1940s, during which time the SAS in particular operated as a group of small strike teams, deployed behind enemy lines. Over time, though, their responsibilities grew; not only were they running small units to conduct (or counter) raids, but they were also vital for constructing intelligence networks in whatever area they found themselves deployed. Counterrevolutionary tactics, counterterrorism, and surveillance were where they excelled.

Which all sounds quite a bit like what the ISA would later grow to be. King had worked with British agents from those groups and decided to take inspiration from their operations, albeit with some changes of his own. While British intelligence teams were often temporary things, formed as necessary by the SAS. King wanted a more permanent fixture that filled the same purpose; thus the ISA came into being.

They succeeded where psychics failed

If there's one thing that's somewhat widely acknowledged about the ISA, it would be the reason that it came into existence. And the beginning of that story is Operation Eagle Claw — the military plan to rescue those captured during the Iranian Hostage Crisis.

The short version is that Operation Eagle Claw was a massive failure. The slightly longer version is that on April 24, 1980, several helicopters were sent out to carry troops who would rescue hostages taken by students on November 4, 1979, at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran. Poor weather conditions forced officials to abort the mission, and the situation was bad enough that a couple of the helicopters crashed, killing eight servicemen. The hostages weren't freed until January 21, 1981.

The operation only proved that there were problems with U.S. intelligence. (In case you were curious, the military relied, in part, on intelligence gathered from psychics to try and determine what was happening in the embassy. And that's no joke.) Simply put, the U.S., at that time, just didn't have any group that was capable of gathering the kind of intelligence that could have helped Operation Eagle Claw succeed. It didn't take long for military officials to start putting together the group that would precede the ISA (the Field Operations Group) to provide both that on-the-ground intelligence and support that Eagle Claw had been sorely missing.

ISA agents can learn everything about a person

If you're wondering why exactly the U.S. needs so many spy agencies — the CIA, ISA, and other Special Forces units — then know that the answer lies in the types of intelligence provided by each organization. Speaking generally, organizations like the CIA (especially back in the 1980s) were more suited to providing information that would help policymakers and politicians back in Washington D.C. Big picture stuff, in essence.

But what about all the details? Well, that's where the ISA is made to shine. Truly, you can't hide from an organization whose entire existence is to know everything about a person, like their activities from dinner to where they sleep or how armed they (or their bodyguards) were, and even memorizing building layouts where their targets live.

There's tradecraft and traditional spying involved in that, of course, but the ISA has also proved exceptional when it comes to technology. If their target made a call, the ISA has been able to find exactly where that call was coming from, and it only takes them a few seconds at most. Or, if you'd like an even scarier example, the ISA has had tech at their disposal that could remotely turn on their target's phone. They could do so without their target ever knowing that something was afoot, all while the phone began to emit a traceable signal, allowing agents to get into position.

Everyday bureaucrats? Or daring spies?

You know that trope in spy movies, where the dashing agent has to go into hiding or out into the field, whipping out a handful of different passports, wearing new identities wherever they go? Well, as it turns out, that's not something that's relegated only to fiction, because it's part of an ISA agent's skillset.

Writings on some of the ISA's dealings in Colombia in the 1990s explain that ISA agents literally had different sets of official documents for various missions (via Mark Bowden's "Killing Pablo"). And it was more than just creating a convincing paper trail; those documents each corresponded to a particular new identity for the agents, each with their own unique histories and backstories. They were trained to adopt those identities quickly and efficiently, with the process literally being compared to just trying on some new shoes. Fully inhabiting a role was second nature for most of them, which allowed them to blend into the background, often as nothing more than your typical, mid-level bureaucrat.

But it truly was a persona, because the intelligence gathering that these agents could accomplish verges on terrifying. They brought cutting-edge tech that would allow them to pinpoint the origin of a call within just a few seconds, but if the situation was a bit more complicated? Well, then they were perfectly suited to getting more personally involved, sometimes driving at breakneck speeds during early hours through quite literal warzones, then hiding in dangerous places just to get their intel.

Agents were once mistaken for drug dealers

Even with so little known about the ISA, it's been readily recognized that the group is made up of some of the most elite operatives the Army could produce. In fact, that was basically the original brief for the organization. But even top-secret military organizations composed of elite soldiers could have some stumbles along the way.

Generally speaking, in the early days of the ISA's existence, there were a handful of missions they took part in to ensure other military personnel that they were capable of gathering worthwhile intelligence. On the whole, those early missions and exercises went smoothly, and ISA operators were commended for their results. But that's not to say that everything always went quite so well. There were reports of some operations playing host to minor issues, and one training exercise apparently saw problems that the group had never faced in the past, which then led to some serious restructuring of their protocols.

Even wilder though, was a 1986 exercise called Powerful Gaze. The intended goals of the operation aren't common knowledge, though a report mentions an unidentified "major problem" (via 1986 Historical Report) that led to the agents catching the eyes of state authorities. Whatever they were doing led law enforcement to believe that they were smuggling drugs and subsequently apprehend them for their presumed illegal operations. Higher-ups arrived on the scene and smoothed things over, but not without creating new protocols to avoid such misunderstandings in the future.

Recruits are taught to expect the unexpected, often in brutal ways

The ISA requires their agents to be ready for anything. Fittingly, their agents have to be the best of the best, tough both mentally and physically — but even the most elite agents have had to endure brutal training and recruitment processes, regardless of their prior experiences.

Verbatim, secret reports said, "Training is among the most intensive in the US Army" (via Michael Smith's "Killer Elite"), and that's no understatement. Recruits have to prove that they can deal with anything thrown their way, whether those situations test their mental fortitude or physical ability. Or both. Recruits historically have rarely (if ever) been told exactly what they'd be dealing with in the course of their training, and missions would be given to them without warning — literally forcing them to expect the unexpected.

In one case, a mission even involved the recruits just getting dumped in the middle of a desert. No supplies were provided to them — food, water, quite literally nothing more than the clothes on their backs. What they did have, however, was the knowledge that they had to collect intelligence (which was recognized as being nearly impossible to gather). But that's not where it ended. Not even close. They were then deprived of the chance to sleep for multiple days on end, before being dumped into an entirely new situation: navigating an unfamiliar city and spying on a target, all while avoiding the spies that had been sent on their tails.

The ISA had a somewhat friendly competition with the CIA, all while looking for a drug lord

When you think about American spy organizations, the CIA comes to mind pretty quickly. And given that the ISA is also heavily involved in covert operations to acquire sensitive intel, it only makes sense that they'd be compared to each other. And those comparisons actually brought the organizations to a head.

As Mark Bowden describes in "Killing Pablo," while the ISA (operating as Centra Spike) was in Colombia, tracking down notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar, the CIA was running their own operation (called Majestic Eagle) with the exact same goals. And that led to competition. Apparently, agents from both organizations would literally run to phones in order to report their findings back to Washington D.C. After all, whoever got their call through first would be recognized as the real provider of that intel — no prizes for second place, unfortunately.

The rivalry grew more intense, with the ISA explicitly believing their technology to be far superior (and cheaper to operate). And so what better way to settle the matter than with a competition? Both groups had to track the location of a given signal; the accuracy of the results would speak for themselves. And those results did speak, with Centra Spike managing to track the signal within about 650 feet, while Majestic Eagle was more in the range of around 23,000 feet. Not even close, in other words. The CIA ended up pulling their operations in Colombia, and the ISA was awarded plenty of congressional funding.

They have backed both foreign governments and rebels

With the ISA being formed amid the Cold War, it really shouldn't come as much of a surprise that the group would be part of the trend at the time: the U.S. taking an interest in Latin American political affairs to stop the spread of communism.

One of those missions was said to have taken place in Nicaragua, where the left-wing Sandinistas had taken political power. To put a complicated situation simply, the Sandinista government had taken power away from the rather oppressive regime that had preceded it, only to introduce repressive policies of their own. In response, guerilla groups known as the Contras began to form, and the U.S. declared the Sandinista government as Marxist in nature. While there's a whole controversy to do with American support of Contra rebels, it's said that the ISA was also involved in providing that aid.

Then, there's El Salvador, where the opposite was true. Generally, the U.S. provided heavy aid to the right-wing government to stabilize it. More specifically, the ISA was around to disrupt left-wing rebel movements by learning about their plans and passing that information on to local military commanders. Apparently their work was nothing short of miraculous, producing intel that no other group could. (All that said, it should also be noted that the U.S.-supported government was apparently associated with — or potentially shielding — death squads that had previously killed American citizens. So whether this support was a good thing can be debated.)

They weren't used to their full potential during Operation Just Cause

It's an impressive thing that one of the ISA's lesser achievements involves taking down a Panamanian dictator in 1990. Manuel Noriega was an ex-informant for the CIA, but when word began to spread about his involvement in both the drug trade and money laundering, it was only a matter of time before the U.S. would try to oust Noriega from power. Long story short, the operation was a success. And as for where the ISA comes into this? Technically speaking, they didn't have a huge role, mostly providing support to SEAL Team 4.

But, surprisingly, they didn't have more to do with the operation. Despite the overall success, part of the plan involved Special Forces trying to block Noriega from escaping by air. It turned out the entire thing was a waste of time (Noriega wasn't even at the airfield), and four SEALs were killed — something that could have easily been avoided. After all, the ISA excelled at exactly this type of intelligence, but for some reason, they weren't allowed to conduct any surveillance. To go even further, the ISA was apparently one step ahead of the rest of the U.S. government the entire time; they knew about Noriega's part in the drug trade for years and had reported it to their superiors, only for those same superiors to laugh it all off.

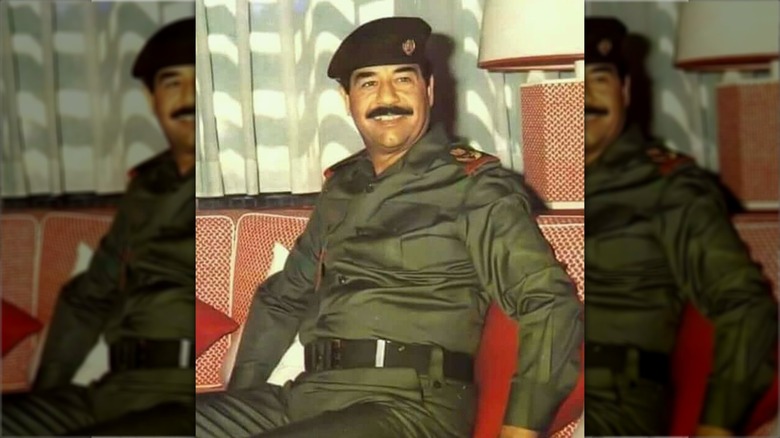

The ISA both helped and hunted Saddam Hussein

Even after the Cold War ended, the ISA's mission didn't, only changing slightly. And perhaps the most storied operation that the ISA conducted during this time is the hunt for the president of Iraq, Saddam Hussein.

Between the ISA's scarily accurate tracking of phone calls and intelligence gathered by their own agents inserted in local communities, they were able to find Hussein's sons. The raid was successful in that it killed both men but also in the unexpected intel they gathered soon after: word from Hussein himself that he was going into hiding, and, thus, his location at the time of that call. Though the operation was far from complete at that point, the ISA did what it did best, unraveling a web of Hussein's allies and prying information from them, until the man himself was finally found.

Interestingly, though, the ISA's history with Hussein goes back much further than this operation. And that history featured a very different relationship between the two. During the Cold War, Iraq was allied with the Soviet Union and looking for more advanced weaponry, which the Soviets were unwilling to provide. And so the ISA stepped in, offering American weapons, provided that Hussein trade Soviet weapons in exchange — a convenient way to learn Soviet military secrets. The deal fell through in the end and no deal was made, but it's quite a far cry from the antagonism that would arise years later.

A failed rescue mission revealed the group to the public

While the Vietnam War was a controversial topic at the time, its aftermath ultimately saw its own fair share of strange stories. One of those stories happened to circle around a former Green Beret known as James Gordon "Bo" Gritz who made it his personal mission to rescue American POWs in Laos. His plan consisted, essentially, of a daring raid through the jungle in late 1982 — and plenty of overconfident zeal and charisma. It suffices to say that the plan was a complete bust, and Gritz had to explain his actions to Congress. Despite the heroic flair he brought, any claims he tried to make in support of his case, such as sightings of American prisoners, were swiftly debunked.

Gritz's character was brought into question, which seems at odds with another part of his story: Apparently, he had help from not only the CIA but also the ISA (although it seemed neither agency knew about the other's involvement). Gritz himself explained that he and ISA agents met frequently to make plans for his rescue mission, with the ISA being invested in the potential intel that Gritz's crew could provide.

The disastrous raid certainly makes it seem like this was a tactical error on the part of the ISA, in the short term, if nothing else. But it would prove to be a long-term error as well, with Gritz's failure being the event that shattered the secrecy that the ISA had enjoyed up to that point, revealing them to Congress.

Government officials considered shutting the group down entirely

Given that the ISA was a highly secretive military operation that was functioning for multiple years without Congressional approval or public knowledge, well, it probably doesn't come as much of a surprise that neither party was the biggest fan.

A 1983 article from The Washington Post sounds less than thrilled by the scarce information provided about the ISA, immediately highlighting unnamed sources accusing the group of illegal and secretive operations, and that all of this was done without proper paperwork. Members of Congress didn't give explicit opinions in that article, though there was a general concern expressed by Rep. Charlie Rose that "Reagan is president and covert action is okay." Which doesn't exactly give the impression that they were particularly pleased.

More concretely, though, a classified memo from 1982 by Frank C. Carlucci, who was deputy secretary of defense at the time, found the ISA's actions to be "disturbing in the extreme ... uncoordinated and uncontrolled." Again, far from a positive reaction. To go even further, that memo implied that the ISA, at least in its form at the time, might not even be a desirable operation, despite the talent that it housed. And if anyone wanted to keep it going? Well, they would need to provide a full plan when it came to accountability, as well as much clearer details on the agency's organization.