The Only Times The Times Square New Year's Eve Ball Drop Was Cancelled

There's been a celebration in Times Square to ring in the new year since at least 1904, and the ball atop One Times Square has been a part of it for nearly as long. The first such ball — a wood-and-iron decoration — was installed in 1907 to mark the beginning of 1908 and was inspired by the time ball installed at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich in 1833 to help ship captains set their watches (per Times Square's official website). New York's purely decorative ball might not keep ships on time, but it's become as much a part of the city's iconography as the Empire State Building, Central Park, and an ongoing war with Chicago over how to make pizza.

Seven different balls have topped One Times Square since 1907, each one an update of materials, lights, and energy. And the balls have had a nearly unblemished record since 1907 — neither weather nor national tragedies nor even a global pandemic have stopped New York from dropping the ball on New Year's Eve (though The New York Times reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did restrict the crowds in Time Square). The only thing that's ever stopped the ball from dropping is World War II — at the end of 1942 and 1943, Times Square and all of New York City were dark as part of the war effort.

Dimouts were a wartime precaution against air raids

Per Mark Caldwell's "New York Night: The Mystique and Its History," after Pearl Harbor there were fears that air raids might target New York City. Within a few months of America's entry into World War II, it was determined that the greatest threat to New York's skyline was the skyline itself, so illuminated that it painted a great big target on the island. As a result, a dimout was put into effect beginning May 18, 1942 — one that lasted nearly three years.

"All illuminated advertising had to be shut off permanently," wrote Caldwell. "Theaters were allowed faint outside lights, but only on the undersides of their marquees ... At home any lamp visible outdoors had to beam downward. Anyone living above the fifteenth floor of a skyscraper with lights visible from the sea had to douse them or hide them behind blackout curtains." Times Square was one of the most dramatically impacted sections of New York — all its famous advertisements had to go dark, and even the news ribbon of The New York Times was shut off.

Reporters who were on the scene described the dimout as affecting the character of New York as much as it did the skyline. Without all its nightlights — and with gas rationing and the draft taking so many people and vehicles off the street — the city that never sleeps found its nocturnal energy noticeably softened.

New Year's Eve was still celebrated in Times Square, even with the dimout

The One Times Square ball was very much included in the list of New York icons affected by the wartime dimout. Per The National WWII Museum of New Orleans, the city had rather defiantly welcomed 1942 with lights, sound, and pageantry, refusing to let Pearl Harbor or America's entry into World War II dim the celebrations. But by the end of 1942, the dimout was in place. Not only did the lights stay off, but the ball wasn't even lowered. The same held true for the end of 1943.

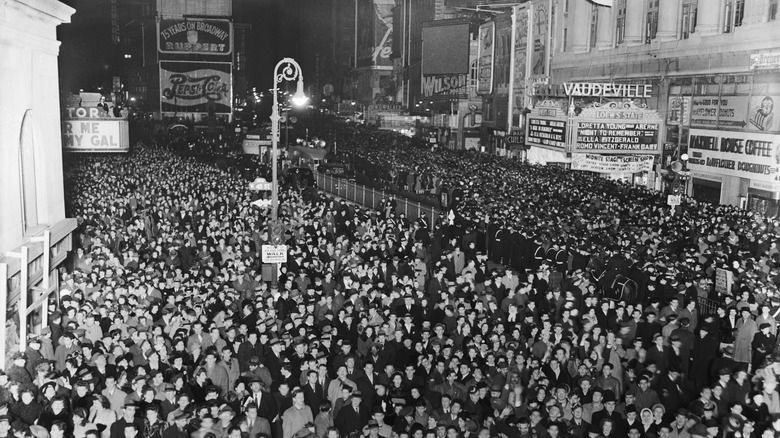

But according to the Times Square Chronicles, dim lights didn't stop New Yorkers from celebrating the New Year. Crowds still gathered in Times Square both years that the ball was still and dark. When midnight came, residents observed a moment of silence, followed by the blaring of truck horns. On New Year's Eve 1943, the Times Square celebrations were complemented by the flocking of many to churches in anticipation of January 1, which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had designated a day of prayer. Though the war still had a few months to go, the ball came back in time to ring in 1945.