The Most Intense Sports Of The Ancient World

As the saying goes, nothing beats a classic. And when it comes to sports, you can't get more classic than the ancient world. Admittedly, that can mean different things to different people. For some of you reading this, the 1980s might seem like an "ancient world" of goofy clothes and classic Rocky films. Here we're applying the definition traditionally used in North America, where "ancient world" generally refers to regions surrounding Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean from roughly 3,000 B.C. until the fall of Rome in 476 A.D.

That was a much more homicidal time for sports, and what athletes did to win in those not-so-halcyon days of gore might be considered criminal nowadays. Likewise, what they endured might be seen as torture — broken bones, horrific disfigurement, and death, all for the sake of saying they out-struggled and out-suffered other hungry competitors who dared to challenge them. "Intensity" isn't an intense enough word to capture the insanity of those times. But it's the best word we've got to describe the athletic tests of antiquity. Here are the most intense sports of the ancient world.

Tent-pegging had high stakes

Tent-pegging sounds like a euphemism for what campers do in the woods when they really love each other, and maybe it is for some extra happy campers out there who are busy not reading this. But for our purposes, tent-pegging is a fast-paced sport for horsemen who probably ran with scissors as children. The goal is for riders to remove pegs from the ground using swords or lances while their steeds run at full speed. While that seems like an elaborate way to maim yourself, it's a useful skill if you're a Macedonian warrior living in the fourth century B.C.

The sport's name refers to a tactic used during morning raids wherein riders would dislodge tent pegs in enemy camps and presumably chuckle as their slumbering foes woke up to a face full of tent. According to the book Pole Bending, Alexander the Great's armies used tent-pegging against Afghan and Indian forces in 326 B.C. It's thought that they also employed a similar tactic against elephants, namely stabbing the animals' feet. However, other sources like House Illustrated suggest that tent-pegging emerged during the Middle Ages. We can't say for sure how dangerous it was centuries ago for someone to thrust bladed objects at the ground while traveling at a high speed atop a muscular animal. But according to tent-peggers in present-day Pakistan, people frequently break their arms or legs and some riders die from competition.

Float like a butterfly, sting like ... broken glass?

In the 3,000 or more years that boxing has existed, there was probably never a time when it wasn't dangerous. In 1950s America, boxing was so brutal that Time described it as "the manly art of murder." But at least the lethal fights of the '50s had weight classes and rounds. Those requirements didn't exist in ancient Greece, where boxing was an Olympic sport, or the Roman Empire, where it was a festival event. As Professor David Potter explained, boxers of all sizes could "just fight till one person's incapacitated." Per the Metropolitan Museum, competitors also fought multiple opponents in a row with short breaks between bouts, and punches were mostly aimed at the face and head.

The earliest boxing gloves were "simple leather straps that covered the forearms," but according to the Met, during the Roman Imperial period boxing gloves for gladiators had broken glass or sharp metal points. However, Vice pointed out that some historians don't believe these murder-gloves were ever actually used. Even if the ancient version of Muhammad Ali didn't float like a butterfly and sting like a stab wound, he probably mangled opponents' faces. The Greek Anthology describes a boxer who "used to have nose, chin, forehead, ears, and eyelids" but apparently got so badly disfigured that he was legally deemed an imposter when trying to claim his inheritance since he didn't resemble his own portrait.

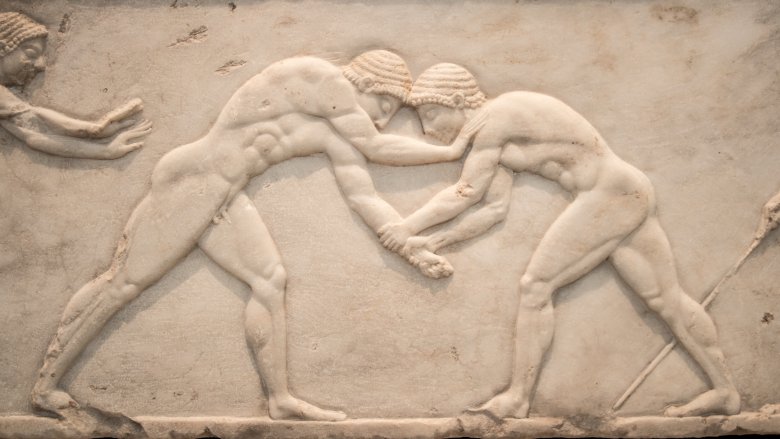

Socrates and Plato wrestled with tough questions and tough men

Wrestling might be the purest athletic test there is. Picture it: Two nude dudes coated in olive oil vigorously gripping and grabbing each other in a sandpit, possibly for hours on end. At least that's how the ancient Greeks did it. (They were big on male nudity.) As Vice described, wrestling didn't have time limits or weight classes back then. However, it did have intellectual heavyweights. Iconic philosophers Socrates and Plato liked to engage in oily tussling. We don't know how well Socrates did, but that's okay because true wisdom is knowing we know nothing. However, we can say that history's smartest ignoramus trained alongside Plato. In fact, "Plato" was a wrestling nickname that referenced the philosopher's broad shoulders. (Plato's real name was Aristocles.)

Apparently wrestling wasn't violent enough to frighten away big-brained thinkers, but as the book Sport in Ancient Times observed, choke holds were a big part of wrestling, and athletes weren't legally liable if they killed someone mid-competition. And there was one vicious competitor, ominously known as "Mr. Fingertips," who defeated opponents by breaking their fingers. That tactic was later, mercifully, banned. Presumably, Mr. Fingertips was like the Mr. Glass to the unbreakable grip of Milon of Kroton, who was associated with another famous philosopher: Pythagoras. Milon supposedly had a grip so strong that no one could pry a pomegranate from his hand. Impressive.

Polo wasn't just horseplay

"Polo" may look like the Spanish word for "chicken," but it describes a dangerous sport in which teams of people on horseback hit balls with really big hammers. Polo originated in Persia (modern-day Iran) around 2,500 years ago and was used to train cavalrymen. The so-called "the sport of kings" was also famously used to throw shade at King Alexander the Great when he rose to the Macedonian throne. Persian Emperor Darius III sent Alexander a polo mallet and ball, advising him to "stick to sport and leave the business of war to those who could handle it." Alexander instead likened himself to the mallet and the ball to the world "he planned to conquer." (He later conquered Darius.)

Ancient polo players put the "war" in "war games." Speaking with the LA Times in 1989, polo club president Don Patch painted a chaotic picture: Two teams of 600 men wielding sticks "just charged at each other" in a no-holds-barred battle "to get the ball through the goal." While the game is much tamer nowadays, an extreme version played in Pakistan may approximate the mayhem of old on a smaller, less deadly scale. Smithsonian's Paul Raffaele witnessed that contest in person, and from the sound of things it was an equine trainwreck. Riders dangerously chased the ball, and one unlucky horse tragically tripped, cartwheeled, and broke its own neck.

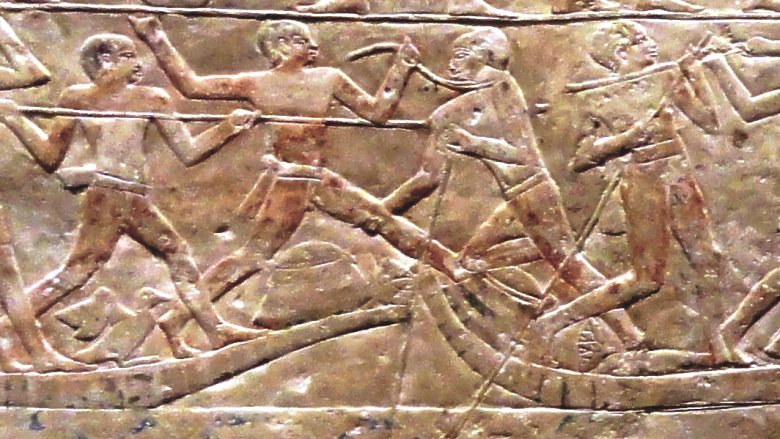

Fisherman jousters became bait for river beasts

Ancient relief carvings tell us that Egyptians walked like the 1980s band the Bangles. Also, they liked hitting each other with sticks. As detailed in Sports and Games of the Ancients, stick fighting served as self-defense and combat training and might have provided a "safe" competitive outlet. It also provided a deadly competitive outlet known as fisherman jousting. As the name implies, fisherman jousting involved fishermen trying to knock each other into the Nile River. It's believed the contents were used to resolve disputes over who got the primo fishing spots or as a form of "good-natured" roughhousing.

Of course, everyone knows it's all fun and games until someone gets eaten by a crocodile, and that was a very real possibility for jousters. Then again, crocodiles were sacred in ancient Egypt, so maybe it was an honor to be eaten by a beast that can grow to 19 feet long. But let's not forget the ginormous hippos that lived in the river and were "notorious for capsizing fishing boats" and wreaking havoc. Some competitors had to worry about more than being eaten by divine reptiles or becoming marbles in history's grimmest game of Hungry Hungry Hippos. Fisherman jousting was literally a sink-or-swim situation, and not all fishermen knew how to swim.

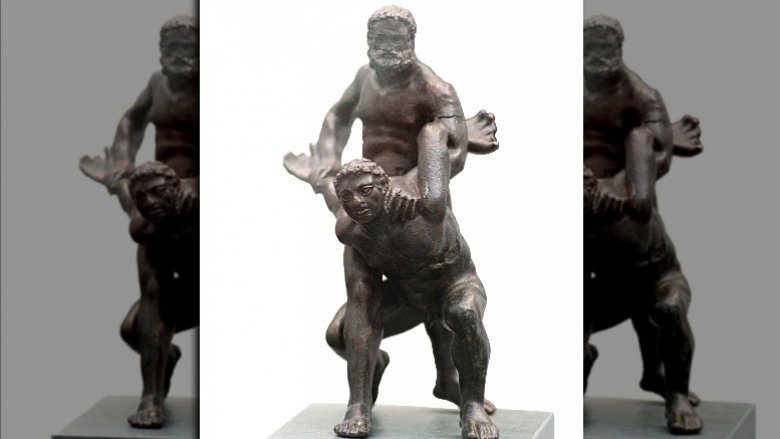

The Pankration was all about strength and strangulation

Some truly ghoulish sports have been cut from the Olympics, such as live-pigeon shooting and pistol duels. But perhaps no no-longer-Olympic sport was more morbid than the Pankration. Dubbed "the grandfather of modern Mixed Martial Arts" by Bleacher Report, the Pankration was an ultra-violent hybrid of wrestling and boxing. Necks were snapped, fingers were fractured, and people were choked to death in strangle holds. Fighters were barred from biting and gouging eyeballs, though not in Sparta, where Gerard Butler would have been free to bite opponents, gouge their eyes, and (probably) bite their gouged-out eyes before beating them to death with his abs.

Pankratiasts wore their birthday suits plus a coating of olive oil, presumably so they could leave the world the way they entered it: naked and slimy. Even winning could kill you — just ask Arrichion. Oh wait, you can't because he's dead. Granted, he competed in 564 B.C., so at some point he would have died from just being alive that long ago, but, that's not why he died. As recounted by Bleacher Report, Arrichion was vying for the Pankration crown against an unknown opponent. At some point the competitor trapped Arrichion in a choke hold. Though he was losing consciousness Arrichion had the wherewithal do dislocate his opponent's ankle, forcing a submission. But it was a pyrrhic victory: Arrichion died.

Bull-leaping or bull droppings?

"Grabbing the bull by the horns" wasn't just a figure of speech if you lived on the island of Crete during the Bronze Age — at least according to some historians. Bull-leapers are believed to have used those horns to jump onto bulls' backs before jumping back off. Glyphics indicate that jumpers also leaped over the length of a charging bull or performed somersaults.

As you might have guessed from the somersaults, ancient Cretans were head-over-heels for bulls. Per National Geographic, Crete was the birthplace of the Minoan civilization, which mysteriously deteriorated around the 15th century B.C. and possibly became the basis for the legend of Atlantis. Minoans viewed bulls as sacred symbols of strength and fertility and showed a cultish devotion to them. They made bull sculptures, bull jewelry, bull paintings, and are famously associated with the Minotaur myth, which for all we know was just ancient bull fanfic.

Some experts think the notion of Minoans actually jumping over bulls is a load of horse pucky. According to the Penn Museum, the most convincing case against bull-leaping as an actual practice is that it seems "physically impossible." But the existence of modern-day bull-leaping in southwest France and Spain debunks that claim. Those who believe bull-leaping happened during the Bronze Age argue that artistic depictions of it evolved in ways that only make sense if they were based on a real sport.

You can't spell 'chariot' without 'riot'

Since Ben-Hur's release in 1959, every article, paragraph, sentence, and fleeting human thought involving Roman chariot races has mentioned that movie. We're continuing that tradition because originality is overrated and the world needs more Charlton Heston references. If you've seen the epic race sequence in Ben-Hur, you know how perilous and terrifying it looked. Well, the real deal was way worse, and not just because of the lack of Charlton Heston.

As PBS detailed, a single seven-lap race at the Circus Maximus contained up to 12 chariots. Nasty crashes were a given, and drivers could also be flung from their chariots, wrapped in their reins and strangled, dragged across the ground, or trampled. At Constantinople's Hippodrome horse-drawn carnage and political vitriol collided. According to National Geographic, two rival chariot teams, the Blues and Greens, saw red when they competed against each other. Eventually verbal jabs escalated in violence.

Emperor Justinian saw fit to execute seven men from both teams. One man from each faction survived, which was seen as a sign that the rival factions should unite. Upset by what they considered excessive taxation, the charioteers mounted a Blue-Green uprising at the next race. The emperor, meanwhile, turned yellow and fled as rioters looted for days. Before long, Justinian's troops "cut the people to pieces and left as many as 30,000 men, Greens and Blues alike, dead on the arena floor."

Gladiators performed in a depraved circus

If life was fair, Russell Crowe would be reading this entry to you aloud and in person while dressed as Maximus from Gladiator. But life isn't fair, and it was terribly unfair to actual gladiators. Their "Maximus" was the Circus Maximus, which, like the Colosseum, was a massive Roman arena where armed combatants killed animals and each other for the amusement of the masses. Fights weren't always fatal and sometimes referees may have intervened to prevent deaths. But the University of Chicago noted that in the first century A.D. a gladiator might have had a 1-in-10 chance of leaving the arena as a corpse. Occasionally the combatants weren't the deadliest part of an event because temporary stadium stands sometimes collapsed, "killing hundreds, even thousands," of spectators who were eager to see people die.

Not everyone thinks it makes sense to apply sports terminology to gladiators. Alastair Blanshard, a professor of classics and ancient history at the University of Queensland, argued that they were more akin to death row inmates since "the vast majority of gladiators" were either war prisoners or condemned criminals. However, History noted a demographic shift in the first century A.D. in which "scores of free men" willfully signed up to be gladiators. A handful of women also entered that bloody fray voluntarily, though most who fought were slaves. Ladies were sometimes relegated to fighting dwarves, but some slayed animals. That is, until female gladiators were banned altogether.

The venatio brought out the beast in people

Nature is cruel, but human nature is crueler. To see that fact in action you need look no further than the venatio. The precursor to Spanish bullfighting — which is thought to have started in 711 A.D., according to USA Today — the venatio was the Roman Empire's unsettling answer to the question "If someone wantonly slaughtered a bunch of captive animals in front of a crowd, would people cheer?" The people responded with an emphatic yes. Lions and tigers and bears — oh, we're not done — and leopards and elephants and bulls and even dogs were all fair game in one of history's unfairest games. They were pitted against human hunters and other animals.

The Atlantic noted that the venatio was a ghastly example of bread and circuses. In fact, "nothing won over voters' hearts better than live exotic animal hunts in the arena." Looking to milk the bloodshed for all it was worth, emperors took the concept of overkill and beat a dead horse with it. Emperor Titus commemorated the Colosseum's opening by holding a 100-day event in which 5,000 animals were massacred. The emperor Trajan once had a staggering 11,000 animals battle each other. Some Romans were repulsed by all the gore. The orator Cicero, for instance, felt the venatio reflected mankind's ugliest qualities.

Mock naval battles turned the Colosseum into a dead sea

If the name "Dead Sea" didn't famously belong to an excessively salty body of water, it would be the perfect moniker for the Roman Colosseum when it was supposedly filled with water for mock naval conflicts known as "naumachiae." "Red Sea" might also work as a nickname because these battles were bloody. Plus, much like the Red Sea, experts are split on the issue of whether naumachiae actually happened in the Colosseum, according to National Geographic. At the very least, mock conflicts occurred on lakes, some of which were manmade.

Naumachiae were sort of the big-budget action movies of antiquity, except the performers were extreme method actors and their method was extreme madness. Emperors employed craftsmen to build theaters, choreographers to make the killing visually appealing, and performers to, well, die. Emperor Claudius organized a mock conflict that incorporated 100 boats and conscripted 19,000 criminals to act as fighters. The historian Tacitus said they fought "with the spirit and courage of free men; and, after much blood had flowed, the combatants were exempted from destruction." Say what you want about those bloodthirsty ancients — they're dead, so it won't hurt their feelings.