The Reason 10 Calendar Days Were Skipped In 1582 (And What Happened Afterwards)

What would you do if you woke up tomorrow morning and realized you had lost a week of your life? And it wasn't because of a really bad hangover or a coma, but because the authorities had decided that the calendar was going to change. As weird as that sounds, that's what some Europeans woke up to on the morning of October 15, 1582. And this wasn't just a Proustian question of searching for lost time. There were practical implications to this as well, such as collecting your paycheck or paying rent for the month. And the fact that it was the pope taking away days of one's life didn't help matters at all.

The calendar as we understand it is a human invention meant to track the changing seasons. But what happens when that calendar becomes misaligned, so to speak? The question of whether or not that really matters came to a head in the 16th century due to how Christians calculated the date of Easter. As a result, timekeeping as we know it experienced a fundamental shift.

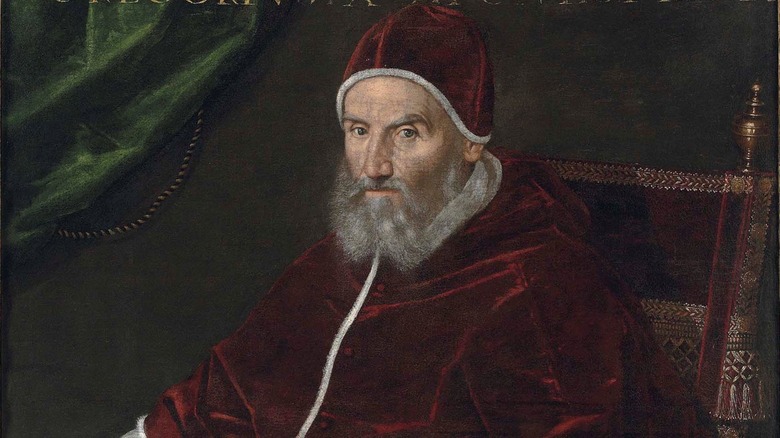

The Gregorian calendar as it's known and used today gets its name from Pope Gregory XIII, who oversaw its creation and installment in 1582. But the road to the implementation of the Gregorian calendar was a rocky one and meant that time had to be sacrificed, one way or another.

Errors in Julian calendar

In 46 B.C. Julius Caesar instituted a new calendar, which became known as the Julian calendar, in an attempt to realign the calendar with the spring equinox and the solar year. The Julian calendar had 365 days with an extra leap-year day added every four years and was closer to the solar calendar's length of 365.2422 days. But in order to introduce the new calendar, Caesar added three months into the current year to bring the Roman Empire's calendar in line with the current solar calendar. As a result, 46 B.C. became the longest year ever with a total of 445 calendar days.

Kinks in the new Julian calendar were relatively resolved by A.D. 12, writes The Conversation, but although the Julian calendar had less of a drift than the previously used Romen calendar, it was still about 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than a solar (or "tropical") year. This meant that the calendar still drifted with respect to the spring equinox and the tropical calendar.

According to Scientific American, the Julian calendar was used for almost 16 centuries before this slight discrepancy became an actionable issue for the Catholic Church. By 1582, a discrepancy that had started as a mere 11 minutes had grown to 11 days. And because the Catholic Church used the spring equinox to calculate the date for Easter, this meant that the drift could push Easter further and further into the calendar year.

Easter and the equinox

Although it might not seem like a big deal today, for early Christians the date of the spring equinox was extremely important, especially for calculating the date for Easter celebrations. In "The Christian Experience," Michael Molloy writes that out of all the Christian festivals, Easter was the first and the most important one. And not only was the spring equinox essential in calculating the date of Easter, but the date of Easter was necessary to have in order to calculate the dates of both Lent and Pentecost.

The method by which early Christians calculated Easter was decided by the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325. and established that Easter was celebrated on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the spring equinox. But because the Julian calendar was slowly shifting the calendar date of the equinox compared to the tropical equinox, it meant that the date of Easter was also shifting with respect to the solar spring equinox.

Although the Catholic Church didn't do anything about the discrepancy until the 16th century, it was noticed and remarked upon by many people well before then. According to "A Brief History of Timekeeping" by Chad Orzel, in 1267 the Julian calendar was described as "intolerable, horrible, and laughable" by Roger Bacon, an English monk, for its inconsistency with the solar calendar.

Pope Gregory XIII changes the calendar

One of the early papal attempts to reform the calendar was by Pope SIxtus IV in 1475. But the person he chose to help devise the reforms, astronomer and mathematician Johannes Müller von Königsberg, also known as Regiomontanus, died after arriving in Rome to work on the calendar, and the project was abandoned.

In 1572, cardinal-priest Ugo Boncompagni became Pope Gregory XIII. Soon after becoming pope, he decided to address the matter of the drifting calendar, having previously worked on the issue with the Council of Trent from 1545 to 1563. A commission was formed to create a new calendar, composed of a variety of people including members of both the Roman and Eastern churches, a lawyer, a historian, an astronomer, and a mathematician. Together, the commission tried to come up with a calendar that appropriately took into consideration the fact that "civil years necessarily consist of integral days," as Jesuit astronomer Christoph Clavius stated, per Scientific American. In other words, you couldn't fix the calendar by just tacking on a partial day at the end.

After the commission submitted their final report in 1581, Pope Gregory XIII prepared to announce the new calendar.

Reasons for the changes

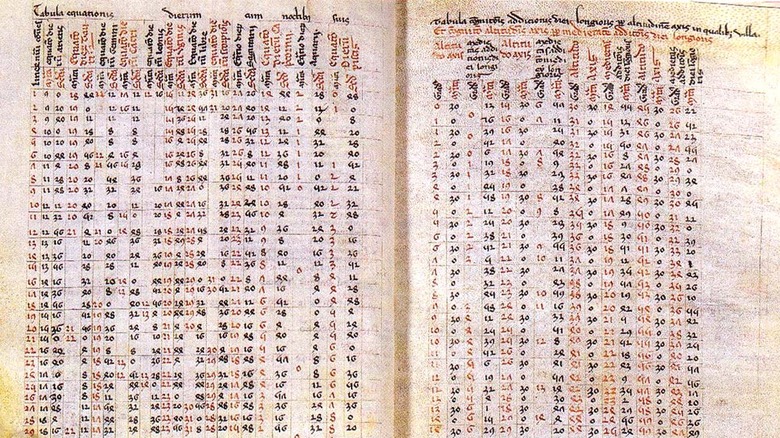

The calendrical reforms of "Inter gravissimas," the papal bull that introduced the Gregorian calendar, were largely the suggestions of Aloysius Lilius (aka Luigi Lilio), an Italian physician and astronomer. In "The Calendar," David Ewing Duncan writes that the commission initially struggled with how to determine the exact length of a solar year. Not only did the current length of the year differ from the length recorded by Ptolemy, but there was also the growing debate between Ptolemaic and Copernican thought. Lilius decided to bypass this by simply basing his estimate on the popular Alfonsine Tables, astronomical tables from 1252 that were based in Ptolemaic theory and used for calculating the position of the planets. And once the length of a solar year was established, it was simply a matter of figuring out how to realign the two calendars.

There were a couple ideas considered as to how to get the calendars back in sync, ranging from dropping a day roughly every 134 years to skipping 10 leap years over the course of 40 years. But ultimately, it was decided to do it all in one fell swoop. Unfortunately, the exact reasons behind this decision are unknown due to Lilius' submitted manuscript being lost.

But despite the science behind the calendar reform, Pope Gregory XIII's introduction of it became a political document. Because Gregory was taking up the actions of the Council of Trent, a Counter-Reformation council, the reform was seen as illegitimate in the eyes of Orthodox Christians due to references to the council in the papal bull.

October 1582

The Gregorian calendar that the commission had come up with followed some of the ideas of the Council of Nicaea while also making contemporary political compromises. Because of this, the date for the spring equinox was set at March 21, where it continues to be to this day. And in order to realign March 21 with the solar spring equinox, the commission decided to take 10 days off of the year in 1582.

The papal bull "Inter gravissimas" announced in February 1582 that the year was going to have a 10-day shift in the calendar in order to realign the dates of spring equinoxes with the solar calendar. It was decided by the commission that the 10-day shift should happen in October, moving from October 4 directly to October 15, because it didn't conflict with any important feasts or major saints' days during that time.

With this jump, the calendars would be realigned and the new rules of the Gregorian calendar, having been decided by the commission, would be implemented. A man whose brother had been on the commission, Antonio Lilius, was given the exclusive contract for publishing the new calendars with the Gregorian system. But he was unable to fulfill the large number of orders for new calendars, and by September 1582, the publishing contract was given to someone else.

The difference between the calendars

At first glance, there's little difference between the Julian and the Gregorian calendars, which both include 365 days with occasional leap years adding one day to the year. But the method by which the Gregorian calendar addressed the issue of aligning the calendar year with the tropical year was slightly more complex and more precise than that of the Julian calendar.

The Julian calendar introduced the concept of leap years adding a day to the calendar, but because the Julian calendar added an extra day every four years, it made a calendar year 365.25 days long, roughly 0.0078 solar days longer than a solar year. While Aloysius Lilius' system for the Gregorian calendar also followed the concept of adding another day with a leap year every four years, Lilius decided to drop the extra day if the leap year date was a century year that was not divisible by 400.

Additionally, the ecclesiastical calendar, or the Catholic Lunar calendar, was also reformed by Lilius in order to keep the date of Easter consistent with the lunar calendar. This involved a series of rules for shortening days or dropping them altogether, but because they're set on a 2,500-year old cycle, some of the rules have yet to be used.

Public response

When the calendars officially skipped from October 4 to October 15, 1582, not everyone was ready to accept the transition smoothly. Effectively, people had lost 10 days of their lives, and it wasn't quite clear what was going to happen with those 10 days. Projects were suddenly due 10 days sooner, but what about the wages that were to be collected during those days? There was also the issue of how to pay a month's rent or collect interest.

Others expressed concern that the saints that had their days skipped over might be upset by this change. And the fact that not all regions across Europe adopted this change likely didn't help the situation. It's not easy to take days off of one's life when there's the knowledge that the 10 days are still there across the border, or even in the next town over. Anti-Gregorian astronomer Michael Maestlin even scared people by claiming that the pope had literally stolen 10 days off of everyone's lives.

According to "Thomas Harriot" by Robyn Arianrhod, there was enough of a public backlash against the potential loss of 10 days that it persuaded Queen Elizabeth not to accept the reform, even though the new Gregorian calendar was more accurate with regards to the solar calendar. And the fact that it was the pope who was imposing these reforms didn't help sell the idea on a continent experiencing waves of Protestantism.

Protesting the new calendar

As European countries embraced Protestantism throughout the 16th century and moved away from seeing the pope as an authority who could command non-religious aspects of peoples' lives, the idea of having the pope dictate something like the calendar seemed like a great violation. In places like Frankfurt, Germany, people protested both the pope and the mathematicians who'd helped reform the calendar for supposedly conspiring to steal peoples' wages. And James Heerbrand, a theology professor in Tübingen, Germany, called Pope Gregory XIII a "calendar maker" and "the Roman Antichrist."

In both Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries, the Gregorian calendar reform wasn't implemented at first and would take years to be introduced. As a result, some protests against the calendar came centuries later, when countries finally made their respective shifts. In 1752, when Britain made the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar and lost 11 days, people protested in what became known as the Calendar Riots.

France, Italy, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Portugal, and Spain were some of the first countries to incorporate the new calendar reform into their timekeeping, as those countries were all heavily Catholic at the time.

Some countries kept the Julian calendar

Some countries, like the United Kingdom, didn't make the switch to the Gregorian calendar for almost two full centuries. Parts of Germany varied in when they accepted the Gregorian calendar, and some regions actively resisted reforming their calendar for decades. Other countries, like Belgium and the Catholic states of the Netherlands, didn't make the switch until the end of the year, which meant that their calendars jumped from December 21, 1582 to January 1, 1583, which meant a year without Christmas.

Most Protestant countries ended up adopting the calendar reform but did so without referencing the pope in any way in their announcements. Among Protestants, one of the prevailing ideas agreed with Martin Luther's sentiments that religious authorities shouldn't be in charge of timekeeping for a society. Others, among both Protestants and Catholics, believed that the Julian calendar was created by God, ironically a position that the church itself had taken for centuries.

In many places, it was neither a calendrical nor a religious desire to change calendars that led to the eventual shift but the fact that it was comparatively difficult to conduct international trade with two different calendar dates.

Adopting partial reforms

By the 1700s, countries like Germany and Denmark finally started making the Gregorian changes to their calendar. But they did their own calculations for Easter, creating a Protestant Easter calendar. As a result, years like 1724 and 1744 ended up having two dates for Easter celebration depending on which calendar was used. Germany wouldn't fully switch to the Gregorian calendar until 1775, when Frederick the Great outlawed the Protestant Easter calendar.

And in places like Sweden, the German Protestant Easter calendar was adopted but instead of dropping 10 days they dropped only one, leading to a new calendar entirely in 1700. According to "Essays on Astronomical History and Heritage," Sweden's King Charles XII introduced a plan that involved deleting 11 leap days starting in 1700. This would align the Swedish calendar with the Gregorian calendar by 1740. A little over a decade later, Sweden switched back to the Julian calendar, following a decree sent by the exiled Charles XII from the Ottoman Empire. In 1753, Sweden adopted the Gregorian calendar and made the necessary realignment by going from February 17 to March 1.

However, Sweden also used a different calendar for Easter and celebrated Easter on a different day from the rest of Europe until 1844.

Over four centuries of conversions

Overall, it took almost 400 years for the Gregorian calendar to be adopted fully across Europe. Russia was one of the last countries to make the switch in 1918. This is why the Russian October Revolution is called as such despite now being dated as occurring in November.

During the adoption of the reform in the British Colonies in North America in 1752, writers like Benjamin Franklin reassured his readers that the loss of time was nothing to lament, and to consider "what an indulgence is here, for those who love their pillow to lie down in peace on the second of this month and not perhaps awake till the morning of the fourteenth."

And the shift to the Gregorian calendar wasn't localized only to Europe. In South America, Spain and Portugal imposed the calendrical reform on their colonies in the 16th century. Across Africa, traditional calendars were typically kept until they were forcibly discouraged by the respective European colonial authorities. Meanwhile, in Asia, the Meiji emperors introduced the Gregorian calendar to Japan in 1873, and in China, the Communist Party adopted the Gregorian calendar on October 1, 1949.