Everything To Know About The Seven Symbols Of Kwanzaa

Celebrations, traditions, and holidays don't have to be ancient to be incredibly meaningful. Just look at Kwanzaa: 2016 was a particularly significant year, as it marked the 50th anniversary of the holiday. But the symbols and meaning folded into this new holiday are rooted in age-old beliefs that make it a moving, beautiful tribute to African culture.

The holiday was created by Dr. Maulana Karenga, who spoke with the Los Angeles Sentinel around the milestone anniversary. In addition to being grateful that he had seen Kwanzaa spread far and wide while bringing so much meaning to so many families, he shared that he had created Kwanzaa alongside the Nguzo Saba. What is Nguzo Saba? Those are the seven principles developed and written to serve as a guiding light in helping people live their lives in the best way, to have a positive impact on the world around them, and to help make sure the next generation inherits a better world.

Karenga says that he had three goals behind Kwanzaa: "First, it was to reaffirm our rootedness in African culture, because we had been lifted out of our own culture and made a footnote and forgotten casualty in Europe's culture and history. ... Second... to give us a time when we as African people all over the world could come together, celebrate ourselves... [And] Third, ... to introduce and reaffirm the importance of communitarian African values." That said, let's take a look at exactly what the seven symbols of Kwanzaa mean.

Mkeka, the place mat

Weaving is an art form that's been passed down through generations. It once allowed for the creation of tools — like fishing nets and baskets — that were life-changing, and today, that long heritage is reflected in a craft that's developed community- and even family-specific patterns and styles that are passed down from craftsperson to craftsperson.

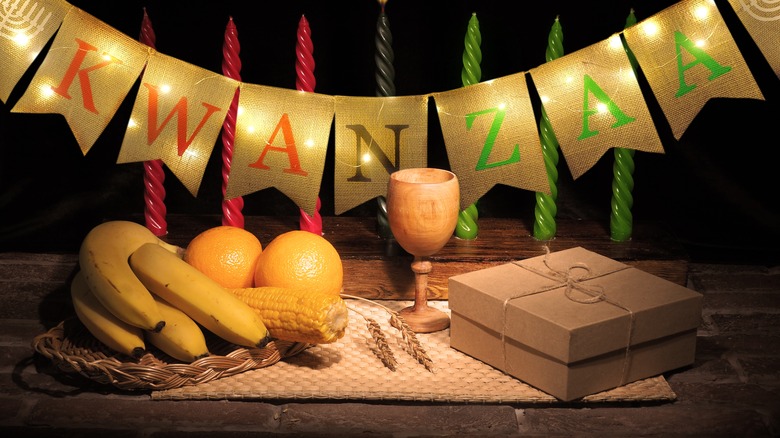

It makes sense, then, that the mkeka is used as the foundation of the other symbols of Kwanzaa. A mat that's placed on the table beneath the other symbols, and it's typically sourced from Africa. They're not just beautiful, they're incredibly personal, too: Materials used are usually local to the area that it came from, and can include things like Kente cloth or various plant fibers. Designs often speak to an art form that's been passed down through families.

There's a bit more to it, too, and the woven mat is also representative of history itself. Just as the piece would fall apart if one strand was removed, it's the same with human history: Everyone has their part to play, and it's important, interconnected, and has an impact that reaches far into the future.

Mazao, the crops

At the heart of the Kwanzaa celebration is mazao. Simply put, those are the crops that are honored for both sustaining entire communities and being the product of the hard work of those same communities. Most importantly, they're symbolic not of survival and a meeting of basic human needs, but of the shared responsibilities, teamwork, and hard labor that goes into planting, growing, and harvesting.

Mazao is usually represented by fruits, nuts, and vegetables, but food is an important part of the entire celebration. That culminates in a meal called karamu, which brings together traditional foods from different cultures into a massive feast held on the sixth day of Kwanzaa. Different families might include different foods, but there are two staples: Black-eyed peas (symbolizing luck) and collard greens (symbolizing good fortune).

The importance of crops is much deeper than simple sustenance, and it harkens back to the many, many harvest festivals held across Africa — and across the generations. Those festivals were held across the continent, but there was one in particular that Dr. Maulana Karenga had in mind when developing Kwanzaa: the Zulu festival of Umkhosi. In "Kwanzaa: Black Power and the Making of the African-American Holiday Tradition," Keith A. Mayes writes that while some of the long-held traditions associated with Umkhosi — like the sacrifice of a bull and the planting of seeds — weren't included in order to make celebrations more accessible, many remain.

Vibunzi/Mihindi, the ears of corn

At a glance, it might seem like corn would be folded into mazao, but it's a very separate thing. Different types of corn are grown all across Africa, but it's not just a food — it's also commonly found in festival- and celebration-specific dishes, like the cornmeal cakes and corn pudding popular during Nigeria's yam festival. But it's also rich in symbolism: it's often connected with harvest festivals — like the ones that inspired Kwanzaa — and it's also representative of fertility and the continuing of family lines, as well as ancestral connections.

It's in that way that corn is symbolic in the context of Kwanzaa, when families use a single ear of corn (vibunzi) to represent each child. (Multiple ears are referred to as mihindi.) In child-free homes, celebrants still add two ears of corn to the Kwanzaa display as a reminder that everyone in the community isn't just responsible for their own, biological children, but they're also responsible for providing guidance, safety, and a future for the children of others.

It harkens back to the idea that it takes a village to raise a child, and here's an interesting tidbit. When NPR did some fact-checking to see just where the oft-repeated proverb came from, they found there was no consensus. African studies professor Lawrence Mbogoni did say, though, "[It] reflects a social reality some of us who grew up in rural areas of Africa can easily relate to. ... The concern, of course, was the moral well-being of the community."

Mishumaa Saba, the seven candles

One of the most recognizable symbols of Kwanzaa is the seven candles, known collectively as the mishumaa saba. They're steeped in symbolism, and let's start with the colors: Red, green, and black. The first and perhaps most obvious connection is to Marcus Garvey's iconic flag, officially adopted by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1920. Garvey created the Pan-African flag to put a black stripe in between a red that symbolized bloodshed and a green that harkened back to the fertile, lush lands of Africa.

There's another layer to this, too: Even as the green represents the land and the black represents the people, the red is also connected to the Yoruba god of fire, lightning, justice, and righteous war. According to the stories, Shango was once a mortal man who died by suicide after being deserted by most of his followers, then ascended into divinity and fulfilled his destiny.

Each of the candles is connected to one of the seven principles of Kwanzaa, and the general idea is that when another one of the candles is lit on each of the days of celebration, it starts a conversation about not only what each principle is, but what it means and how it can be applied to daily life. The last candle to be lit is the black center candle, symbolizing Umoja, or unity. It's an incredibly lofty concept that involves togetherness and harmony not only on a personal and familial level but also on an international and racial scale.

The principles of the green candles

In both Marcus Garvey's Pan-African flag and the many traditional beliefs that Kwanzaa draws on, green represents the earth, the harvest, and life. By extension, the three green candles have been linked to three of the main principles of Kwanzaa: Nia, Ujima, and Imani. The practice of lighting the candles serves as a reminder to illuminate those principles and keep them burning in the forefront of everything one does and chooses to do, and it's a pretty powerful message.

Nia is defined as "purpose," and at a glance, that can seem kind of vague. In the context of Kwanzaa, though, it's contributing to the shared responsibility of community development. Ujima is a similar concept that's defined as "collective work and responsibility." What's the difference? That has a focus on problem-solving, and working together to make the world a better place for everyone in the community.

And how about Imani? That's faith, but not in a religious way. Kwanzaa creator Dr. Maulana Karenga has stressed that there is absolutely no religious component to the holiday, that it's often celebrated alongside religious holidays, and it's focused instead on a rich cultural heritage. Faith, then, is faith in others in the community and faith in the idea that struggle will one day be rewarded.

The principles of the red candles

Just like the three green candles, the three red candles lit during the Kwanzaa celebration are also linked to several of the principles: Kujichagulia, Ujamaa, and Kuumba. Kuumba, or creativity, is as difficult to achieve as it is straightforward to understand: It's embracing new ways to make communities better places for future generations and ensure they inherit something that speaks to heritage, culture, and community.

Ujamaa is also pretty straightforward, and it's a movement that's been gaining popularity in all different communities as people start to push back against the dominance of companies like Amazon and the big box stores. It's the idea of cooperative economics, and it's the idea that we need to support local (and in this case, specifically Black-owned) stores, businesses, and services.

And finally, Kujichagulia refers to the process of self-determination, and it's perhaps best summed up by this quote from Daniel Black's "The Coming." He wrote: "We didn't know we wouldn't return. We simply believed some terrible calamity had befallen us, that our Gods had let tragedy come because we had not honored them. But we were wrong. We were warriors and hunters, poets and jali, farmers and soothsayers. We were magicians and healers, artisans and thinkers, writers and dancers. We were fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers, cousins and kinsmen. We were lovers. And we were home."

Kinara, the candleholder

While the basics of Kwanzaa are laid out in symbolism, those symbols also leave room for personal touches and interpretation. That's the brilliance of the creation of Kwanzaa: At the same time it allows for people all over the world to celebrate it together, there's plenty of freedom for each family or even community to create their own traditions and heirloom pieces that can be passed down to the next generation.

And that's particularly true of the kinara. For the candleholder of the seven mishumaa saba, there are pretty much no rules about what it has to be — aside from the fact that it needs to have separate and distinct holders for each of the candles. Otherwise, it can be absolutely anything. Want something that fits in with decor that says Upper-West-Side-Manhattan-chic? It's out there! Want something made in an arts-and-craft day after foraging driftwood with your child? That's pretty perfect, too.

As the candleholder holds representations of the seven principles, it makes sense that it represents the ancestor. Ancestor worship has been a key part of African beliefs for generations, and today, the kinara serves as a reminder that those ancestors are still watching over their descendants today.

Kikombe Cha Umoja, the Unity cup

As with the kinara, there's no wrong way for the kikiombe cha umoja to be represented in a Kwanzaa celebration. As the unity cup, the idea is simply that it allows for a drink to be shared among a group, whether that's a family or a congregation. It makes sense, then, that it can either be a single cup shared among all in attendance, or every person might have their own cup to drink from, and here's the important part: There has to be a portion of the drink poured out to honor the ancestors who have passed on and who continue to watch over the land and their descendants.

How that's done can vary greatly, but it typically falls to the oldest person to pour out a bit of the drink — no matter what it is — to each of the four cardinal directions. (That drink can even come from a cup and a portion set aside specifically for the ancestors.)

It's called a libration ritual, and it's incredibly moving — especially for those who have lost loved ones, and for whom grief colors the holidays with a grim shadow. When The New York Times spoke with the Brooklyn-based Yoruba priest Ade Ifaleri Olayinka, he explained that it had been passed down through generations of enslaved peoples who held onto their ancient roots. "The libation opens up to give praise to God first, and then it is to honor the earth and those who walked on the earth before us," he added.

Zawadi, the gifts

On the final day of Kwanzaa, gifts are exchanged — and it's not as easy as just picking out the first thing that gets pushed through your Facebook feed on deadline day for ordering. The zawadi are meant to be deeply meaningful, and to tie with one or more of the seven guiding principles of Kwanzaa. That means shopping local, shopping Black-owned, or doing a deep dive into your own creativity and making something special: Because everyone knows, the best gifts come from the heart.

Gift-giving seems so commonplace that it might not be anything special, but Terry Y. Le Vine of UCLA's Fowler Museum of Cultural History explained to the Los Angeles Times that when it comes to what makes humans, well, human, gift-giving is actually pretty high on the list. Le Vine cites traditions among groups like the !Kung as being about much more than just the gift, but of lifelong bonds built around generosity and thoughtfulness. And when gifts are passed down through generations, it's a connection that transcends time.

And that's what zawadi are meant to be: Meaningful, thoughtful, and sentimental gifts that remind recipients of the guiding principles promoted by Kwanzaa. They might be handmade, they might not be, but they're always reciprocated. And here's the beautiful thing: Giving a zawadi gift is a tradition among those considered family, so giving to friends, neighbors, and even coworkers means that those people are now, too, part of the family.