The Disturbing True Stories That Inspired Deadwood

The story of HBO's Deadwood has long been one of television's great tragedies — not because of the story, but because that story never had the chance to come to a satisfactory end. Just when it looked like fans were never going to get the resolution they deserved, that all changed with the announcement of an honest-to-gosh-dang movie. It's got fans old and new revisiting the series, and that brings up an important question: Since Deadwood was a real place, how much of the ultra-gritty, uber-violent, super-dark tale that HBO spun is based on true events?

A surprising amount, actually. A lot of episodes, elements, and characters were plucked out of history and recast for the screen, and sure, there's some creative license here and there, but heck, the history of the Old West is so chock full of creative license that it's already hard to tell where the history stops and the legend begins. But sometimes, truth really is stranger than fiction.

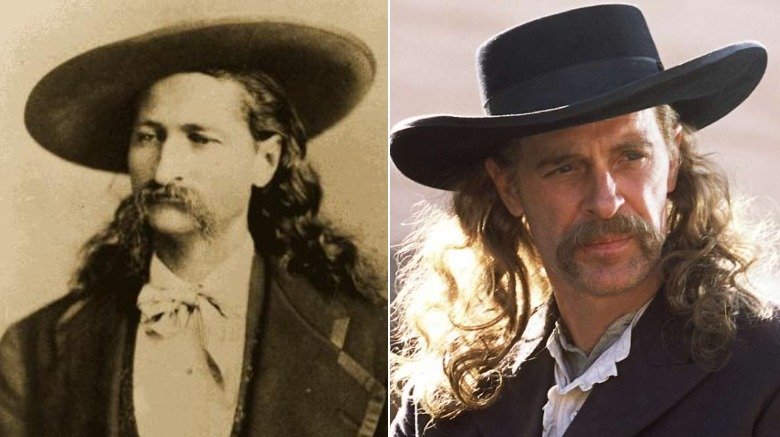

Wild Bill and the dead man's hand

At a time when most were hardened by the circumstances of life, long-time associate Captain Jack Crawford described Wild Bill Hickok like this (via Legends of America): "He was loyal in his friendship, generous to a fault, and invariably espoused the cause of the weaker against the stronger one in a quarrel."

Hickok headed to Deadwood in 1876, and in a story that should sound familiar to fans of the show, he did a ton of gambling. He was on a hot streak at one August poker game, but found himself forced to sit with his back to the door. Jack McCall — who had not only lost a ton of money but who'd been arguably humiliated when Hickok returned some of his money and told him to get something to eat — had already been drinking. He pulled out a pistol and shot Hickok once, in the back of the head. He was killed instantly.

According to popular mythology, Hickok had been holding a pair of eights, a pair of aces (all clubs and spades), and the jack of diamonds. That's now called the dead man's hand, but how accurate is that? According to Arizona historian Marshall Trimble (via True West) that story wasn't told until the 1920s, and the only contemporary reference to the cards actually refers to Bill Massie beating Bill's king full house with four sevens. Most likely? No one checked.

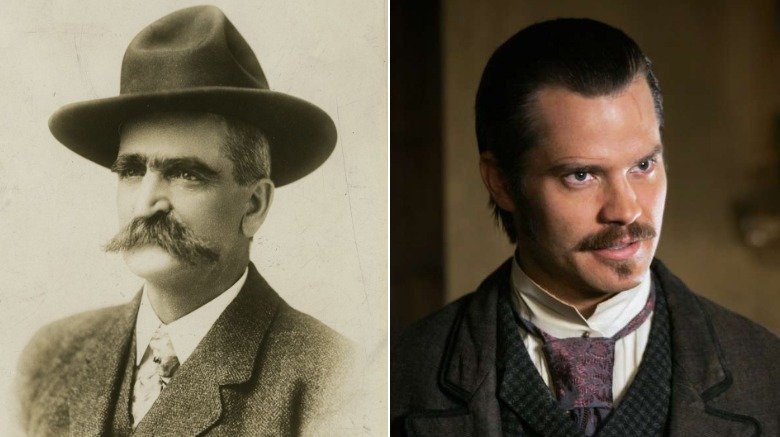

When justice and hangings were public affairs

When it comes to the larger-than-life figures of the Old West, the name Seth Bullock doesn't carry the same kind of weight as contemporaries like Wyatt Earp. But it should, because according to the Theodore Roosevelt Center, Bullock was there for Hickok's murder (the story goes that he and his business partner, Sol Star, had gotten to Deadwood just the day before), and he'd come from Helena, where he had presided over the first legal hanging in the territory.

That scene in Deadwood where Bullock confronts a mob hell-bent on hanging a man is based on what's probably best described as a true legend. According to the tale told by Kermit Roosevelt (via Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman), the man who met his maker at the end of that rope was supposed to die at the hands of a hangman. A mob of vigilantes stepped in, and rather than let mob justice get the satisfaction, Bullock held them off with a pistol and did the hangman's job himself.

But the story is likely Bullock's own invention, because newspapers reported that the trouble they'd expected never came. There's a "but" though: The hanging was a very public affair, with hundreds of people lining rooftops to get a bird's-eye view of the proceedings. And that was against territory law, which stated Bullock's duty was to perform the execution in private with just a few witnesses.

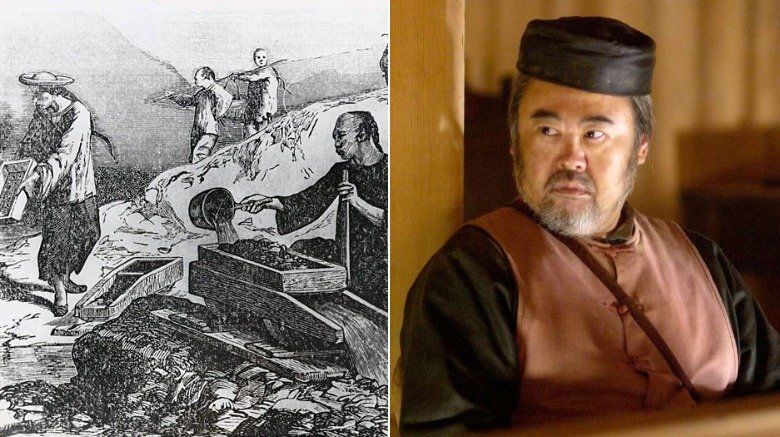

Feeding 'em to the pigs

Deadwood's Mr. Wu was notorious for his method of disposing of inconvenient corpses: He'd simply feed them to his pigs. Was there any truth to it?

Ehhhh. Deadwood really did have a group of Chinese residents, but Jerry Bryant, the resident archaeologist and research curator of Deadwood's Adams Museum says (via True West) that's about where the historical accuracy ends. Bryant says there were no instances of feeding anybody to the pigs, but it wasn't entirely creative license.

In 2002, police raided a Vancouver farm belonging to Robert Pickton, who would eventually be revealed as one of the most notorious serial killers in recent history. He would ultimately confess to murdering 49 women (noting his regret at not hitting his goal of 50), and according to the Independent, feeding the dismembered remains of his victims to his pigs was one of his favorite disposal methods. (It's also believed he may have ground up other remains, mixed it with other types of animal-based mince, and sold it.)

That's definitely not the only story of pigs eating people, and they're not all so murder-y, either. In 2012, a Vietnam vet named Terry Vance Garner was eaten by his pet pigs in unclear but probably accidental circumstances (via the BBC). So the whole thing is plausible, even if it didn't happen in Deadwood.

Truth or caricature?

What about Mr. Wu himself? Deadwood's Chinese population is of the shadowy and mysterious sort, but what's the real story? Fortunately, it's been preserved by the research curator and resident archaeologist of Deadwood's Adams Museum, Jerry Bryant (via True West).

Bryant says Deadwood's real community of Chinese immigrants lived on a section of Main Street called the Badlands, and many had moved from China to the U.S. in hopes of striking it rich. But when they got there, most weren't allowed to stake mining claims because racism isn't a new thing. (One man — Fee Lee — did stake a claim in Deadwood in 1876, but his story is the exception rather than the rule.) Even so, Deadwood ended up having a large Chinese population of at least 110 people, according to 1880 census records, and about half of Lawrence County's Chinese were in the laundry business.

Why laundries? Because they could save the wash water, sluice it, and get gold dust from the miner's clothes. Brilliant, right?

Most of Deadwood's restaurants were also Chinese-owned, and one of Deadwood's major general stores was Fee Lee Wong's Wing Tsue Emporium. Immigration slowed in the first part of the 1880s with the passing of 1882's Chinese Exclusion Act, but Deadwood continued to embrace their Chinese residents, especially a group that organized into a firefighting force and was dubbed "the fastest Chinese hose team in the world."

Opium to pass the time and hide the pain

Part of the appeal of Deadwood was the idea of telling a raw, profanity-laden story without idealization, and that goes for the drug use and addiction of some of the town's residents. That was very real, and the substances of choice were alcohol and opium.

According to the Smithsonian, morphine was a brilliant new cure-all in the 1870s. Doctors administered it for everything from headaches and asthma to stomach pains, so it's no wonder people got addicted. At its height, about 1 in 200 Americans were addicted to opiates in some form, an addiction that was undoubtedly encouraged by the 12.8 million doses of opium pills, powders, and tinctures handed out during the Civil War.

But women made up the majority of opium addicts, mostly because it was so regularly used to treat distinctly female conditions like menstrual cramps and morning sickness. Opium dens were popping up across the U.S. and particularly in the West, where they tended to be operated by Chinese immigrants. (Even Chinese-owned laundries also sold opium accessories.)

Deadwood's mention of the opium trade was very real, and it was perfectly legal in the real Deadwood. According to the Adams Museum, Deadwood's opium dens were both medicinal and recreational, and by 1882 newspapers were already sounding moral alarm bells calling for the end of opium use. That didn't come until 1909 ... legally, at least.

The China Doll: Deadwood's most notorious unsolved murder

Critics might decry Deadwood's undeniable violent streak, but it's perfectly acceptable to argue that's exactly what the Old West was like. The story of the town's most brutal unsolved murder is the perfect example of just how violent it really was.

According to Deadwood historian Jerry Bryant (via HistoryNet), one of the first Chinese residents who came to the town in 1876 was Di Lee, and she was so beautiful she quickly earned the nickname "The China Doll." No one knew exactly where she came from or how she made her clearly abundant wealth, but she was well-off enough to buy three plots of land on Deadwood's main street. Someone didn't like her, though: On November 27, 1877, several people broke into her home and brutally murdered her with a hatchet and a butcher knife.

Her bloody body was discovered in a Chinatown shanty, and Deadwood's coroner determined it was the blows to her head that ultimately killed her. But exactly why and who remains a mystery. There are newspaper reports of suspects being questioned over the murder, but no information about motive or murderers ever came to light, and all newspaper reports of the case stop in 1880.

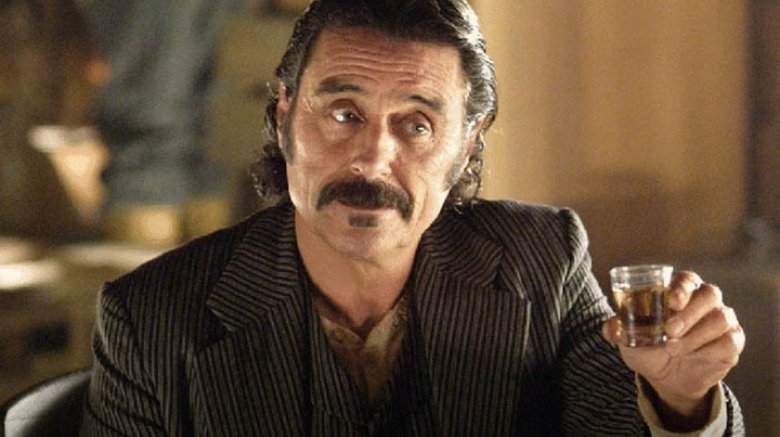

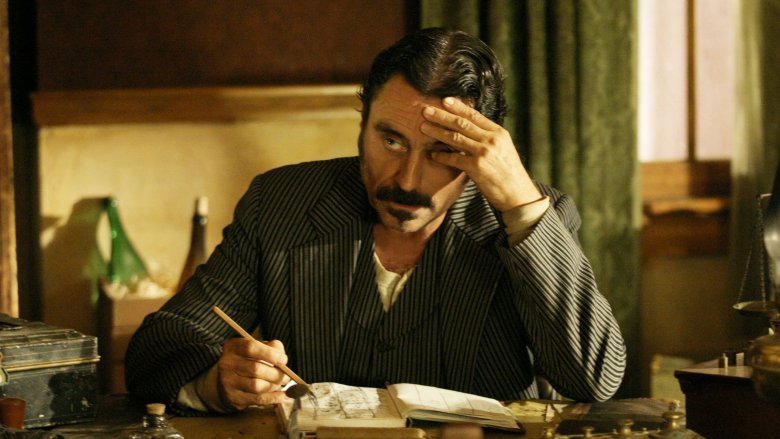

The Gem, Swearengen, and his girls

Larger-than-life and not nearly as nice, Ian McShane's Al Swearengen is one of those characters that just seems highly unlikely to exist outside fiction. But the real Swearengen was just as bad — if not worse.

Born Ellis Alfred Swearengen in 1845 (along with a twin brother named Lemuel), Swearengen found his way to Deadwood in 1876. By the following April, he opened the doors to the Gem Variety Theater. Originally described as "neat and tastefully arranged" (via Legends of America), what went on behind the scenes was anything but.

Swearengen's so-called "painted ladies" ran their business out of curtained rooms in the back of the building, and by all accounts, beatings from customers, bouncers, and Swearengen himself were routine. By the time it burned down in 1899, papers were calling it the "ever-lasting shame of Deadwood," and a "defiler of youth and a destroyer of home ties."

They weren't just talking about women luring men away from their homes and into a den of sin, either. According to Black Hills Visitor, Swearengen lured his painted ladies from around the country. He promised to give them respectable jobs working in his hotel or in private homes, and it wasn't until they got to Deadwood that they realized the job waiting for them was actually prostitution. Those who refused were thrown out onto the street, and some committed suicide rather than work the back rooms of the Gem.

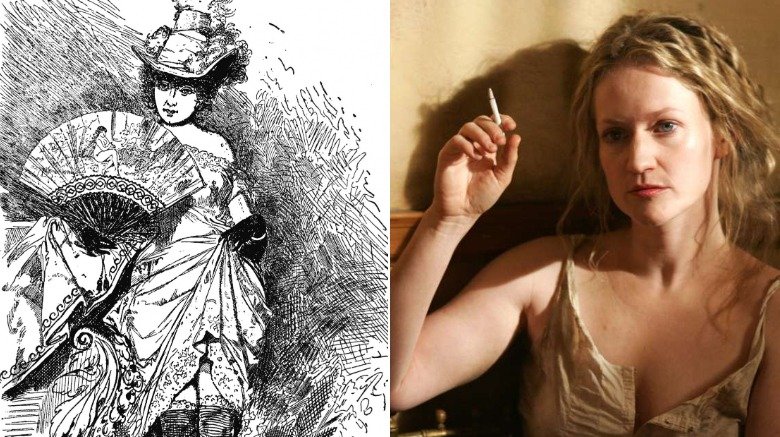

The Gem girls took matters into their own hands

In HBO's version of Deadwood, Trixie is one of Swearengen's girls. When it comes to history, it seems as though she really did have a real-life counterpart ... sort of.

According to Legends of America, the real Gem Variety Theater wasn't nearly as fun a place as the name suggests. In addition to the rooms for Swearengen's painted ladies and regular prize fights, there was — of course — a ton of alcohol and almost as much violence. Flying bullets became a norm, and while they were often aimed at the girls, sometimes it was the girls doing the shooting.

While details are unsurprisingly scarce, there is record of one particular incident involving a Gem prostitute known only as Tricksie. According to the story, she decided to take matters into her own hands after being badly beaten and shot her assailant in the forehead. The story gets even more unsettling: He didn't die immediately, and the doctor was summoned. There was plenty of time, the tale goes, for the doctor to probe around in the man's head and marvel at the fact he was still alive ... at least, that is, until he died about half an hour afterward. History has forgotten the rest of Tricksie's story.

The ill fate of a preacher-man

Deadwood's Reverend H.W. Smith was a very real person, too, and like many who ended up in history's Deadwood, he had a bad end. His might be the most tragic story of all because by all accounts he was an honestly good person trying to do his best to help those in a godless country.

According to Black Hills Visitor, Smith was the first preacher in the area. The Civil War veteran, doctor, and reverend went to Deadwood in 1876, worked odd jobs during the week to support himself, and preached on Main Street every Sunday. On August 20, 1876, Smith left Deadwood after pinning this note to his door: "Gone to Crook City to preach, and if God is willing, will be back at three o'clock."

Smith never returned, and on the following day Bullock wrote a letter to one of Smith's acquaintances, detailing the tragedy of his death. The reverend — who wasn't carrying a gun — was killed on the road to Crook City. He had been shot through the heart, and no one was ever brought to justice. There were a number of theories about what happened: Some claimed he had been ambushed by a group of Native Americans or robbers, but another theory suggests he was killed by a group of Deadwood residents who feared having a preacher in their midst would put a damper on their sinful ways and on the income enjoyed by area saloons and brothels.

Calamity Jane, RN

Calamity Jane was also very real, although tracking down the facts is tricky.

Recent biographer and Dakota Wesleyan University professor James D. McLaird says her real life was probably not super exciting, summing her up as having an "uneventful daily life interrupted by drinking binges" (via Salon). There are, however, some pretty dark episodes in the life of the woman born Martha Canary.

One happened in Deadwood, when a smallpox plague swept through town. She had already survived smallpox as a child and was immune. Working Nurse says that put her in a position to be a caregiver to those suffering from the disease, and she did exactly that at a time when, bizarrely, being a nurse outside of a convent or other religious institution was frowned upon. The illness was deadly, but she saved the lives of five of her eight patients and was later described as "a perfect angel sent from heaven."

There are less angelic episodes in her life, too. McLaird says she was a dance hall girl and prostitute for at least some of her life, and was one of Swearengen's Gem girls in the early days of Deadwood. According to the testimony of Deadwood bartenders, she graduated from painted lady to slaver, sent by Swearengen to neighboring areas to bring back girls for him. On one trip, she was said to have returned to Deadwood with 10 Nebraska girls, tricked into prostitution with her stories of wealth and adventure.

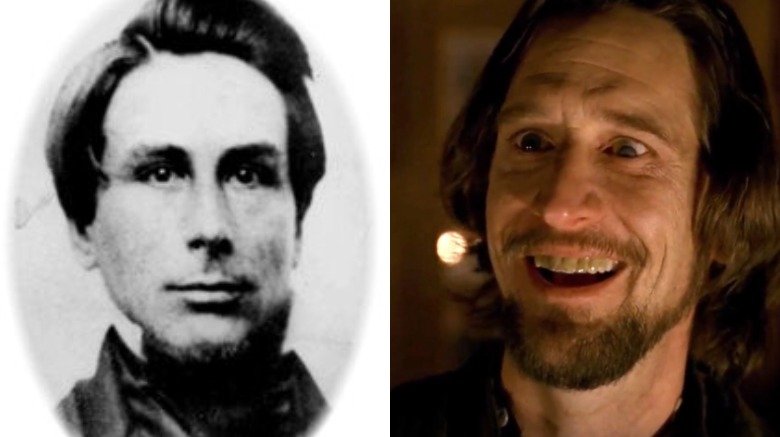

There were no survivors

When news of a massacre reaches HBO's Deadwood, it's the Metz family who has been attacked and murdered — all save one girl, who's brought back to town. The incident wasn't entirely made up for the show, as there really was a Metz family massacred along the Cheyenne-Black Hills Road, not far from the Cheyenne River.

According to author and retired National Park Service superintendent Paul L. Hedren (via HistoryNet), the 1876 Metz Massacre claimed the lives of the entire party, which included Charles Metz, a baker headed to Deadwood, his wife, their cook, and a teamster. As in the show, it was first assumed the attack was the work of local Native Americans, but that wasn't the case. All the Metz family's gold and cash was gone, and word started circulated that it was the work of a shady character called William F. "Persimmon Bill" Chambers.

Chambers was a well-known murderer and horse thief, and the Cheyenne-Black Hills Road was his haunt starting around 1876 — long after he fought first for the South, then the North, then the South again during the Civil War. Not long after the Metz massacre, another attack put Chambers in the sights of the U.S. Army, and newspaper reports seem to suggest he was killed sometime in the fall of 1876 — but they're more colorful than confirmed. As for the Metz party, it's more tragic than it was in the show — there were no survivors.

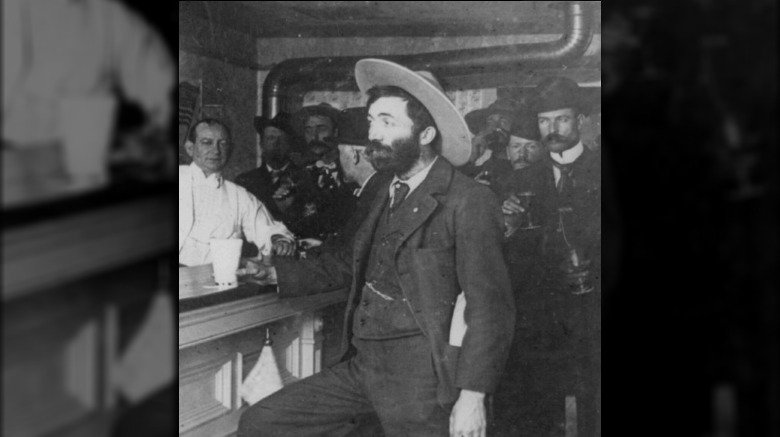

What did the snake-oil salesmen really sell?

The Huckster was exactly that — a huckster, and the Old West was ripe with them. They tended not to stay in one place for too long for obvious reasons, but history hasn't forgotten them.

Among the most notorious of the West's con men was Jefferson Randolph Smith, better known to those he associated with — and those he swindled — as "Soapy" (pictured). While History says one of his earliest cons was charging the public to see his epic "discovery" of a 10-foot "prehistoric man of Creede" (which he'd buried in a Colorado town himself), he was most famous for his soap con.

Smith would head into town with bars of soap he'd be selling for $5. (Adjusted for inflation, that's about $120 today.) Why would anyone pay that much? For a chance at getting the bar of soap that had $100 in it — just like the one the first purchaser (an accomplice) would conveniently find. While it's not clear whether Smith passed through Deadwood before his rather inevitable death at the hands of Skagway, Alaska, vigilantes and a particularly disgruntled engineer, there were plenty more like him.