Every American Ever Convicted Of Treason (And What Happened Next)

It's a word you're guaranteed to hear flooding the airwaves every time a president signs an unpopular bill or a congressperson comes out against bombing some remote nation: "Treason!" But despite what talk radio might have you believe, treason ain't treason in the U.S. unless it meets some specific criteria. Per the Constitution: "Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court." That's pretty precise language, so it should come as no surprise that almost no one has been convicted of treason in U.S. history.

That being said, "almost no one" isn't the same as plain ol' "no one." In the 2.5-ish centuries America has existed as an independent state, a handful of people have managed to do a Benedict Arnold and had it proved in court. Some you probably know. Some — like Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who were actually convicted of espionage and not treason — you only think you know. The rest you're about to find out about.

John Mitchell and Philip Weigel's dubious first

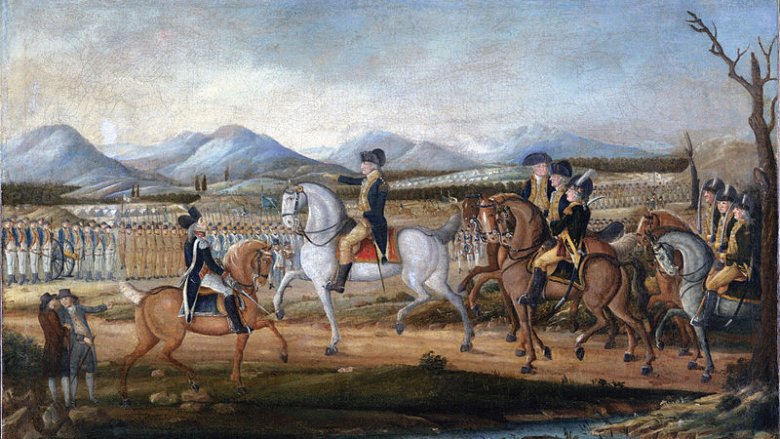

The U.S. Constitution was only ratified in 1788, but before a decade was out two men had already succeeded in hitting its strict criteria for treason. John Mitchell and Philip Weigel were whiskey distillers who'd been thrilled when the United States came into being ... only to watch in horror as one of Congress' very first acts was to hit them with a gigantic tax. Having just, y'know, fought a war against unfair taxes, the distillers not unreasonably assumed the Founding Fathers should practice what they preached. And so began the Whiskey Rebellion, a period of civil unrest that lasted from 1791-95 and saw buildings torched, homes attacked, and at least one tax collector tarred and feathered (via Smithsonian).

After Alexander Hamilton crushed the rebellion, some 150 men were arrested, but only Mitchell and Weigel were unlucky enough to have the necessary two witnesses willing to testify against them on treason charges. They were sentenced to hang, although both received presidential pardons from George Washington, who perhaps recognized the irony of a nation founded on a tax rebellion executing two men for rebelling against what they felt was unfair taxation.

John Fries' violence free rebellion

As rebellions go, John Fries' 1799 attempt was almost painfully ineffective. In 1798, the administration of John Adams (above) decided to hike up taxes on everything, having evidently learned no lessons from the Whiskey Rebellion just four years before. The farmers of eastern Pennsylvania took this particularly badly, formed into armed gangs under the leadership of John Fries, and intimidated local jails into releasing all tax evaders. Adams responded by sending in the troops, Fries was arrested without incident, and that was that.

At least, that was it for the rebellion that carried his name. As Britannica describes, Fries himself was convicted of treason and sentenced to hang. He was actually convicted twice and sentenced to hang, which would have made for an uncomfortable spectacle if they'd tried to hang him a second time. Thankfully, Pennsylvania was spared the sight of the federal government trying to hang a dead man in April 1800 when Adams pulled a Washington and pardoned Fries.

Thomas Dorr's one-man civil war

In 1842, Rhode Island had a problem. Nope, not its needlessly diminutive stature, but that it had two governments. The year before, a people's assembly had been called and a constitution written for the state, which until that point hadn't had one. Unfortunately, the elites in charge refused to recognize the new constitution, so the 1842 election was fought twice, by two sides running under different laws. Samuel Ward King won under the old laws, while Thomas Dorr won under the new constitution. When Rhode Island's government recognized King's victory, Dorr responded by going to war (via New England Today).

Dorr had no military training, and no access to weapons. Still, he scrambled enough men to steal two cannons. He then tried to attack the city arsenal in Providence, only for the stolen cannons to malfunction. Embarrassed, Dorr fled into the night and was arrested and sentenced to life in prison for treason against his state. Not that he served anything like it. His crazy "war" defending the constitution earned him so much respect in Rhode Island that he was freed in 1845.

John Brown fires the starting gun on the Civil War

John Brown was a guy who hated the concept of slavery, to the extent that he once assassinated five random pro-slavery settlers in Kansas to try and balance the books. By 1858, he was openly planning to spark an insurrection among slaves in the South to force the issue of abolition through bullets and bloodshed. In 1859, he finally felt he had the manpower to do it. On October 16, his 21-man army overran an armory in Harpers Ferry, in what is now West Virginia. Brown planned to spark a slave uprising. Instead, his faux army found itself being steam-rollered by Robert E. Lee's actual one.

According to History, Brown was tried for treason against the state of Virginia and, despite making some powerful speeches attacking slavery, was convicted and hanged on December 2. His follower Aaron Dwight Stevens was hanged for the same raid three months later. Their deaths utterly exploded the issue of abolition, turning what had been simmering tension between North and South into a boiling cauldron of mutual resentment. It's likely not a coincidence that civil war erupted just 13 months after Stevens was hanged.

William Mumford fails at tearing down the flag

The sight of someone tearing down the Stars and Stripes in the here and now can be enough to spark a riot. But in the middle of the Civil War? New Orleans gambler William Mumford found out the hard way what happens back in 1862. Shortly after Union soldiers entered his city and raised their flag, it was torn down and replaced by the Confederate one. Interestingly, no one knows if Mumford was actually one of those who tore the flag down, but his fate was sealed regardless. In May 1862, the pro-South Daily Picayune named Mumford as the flag thief and claimed he "deserve(d) great credit." The Union army disagreed.

Word of the article got to General Benjamin Butler, who promptly ordered Mumford arrested and hanged for treason. This being war, there was no trial. Mumford was dragged, protesting his innocence, to a gallows near the U.S. Mint and executed without delay. His death so shocked Southern society that Confederate President Jefferson Davis proclaimed Butler should be hanged in turn if ever captured. That, uh, didn't happen.

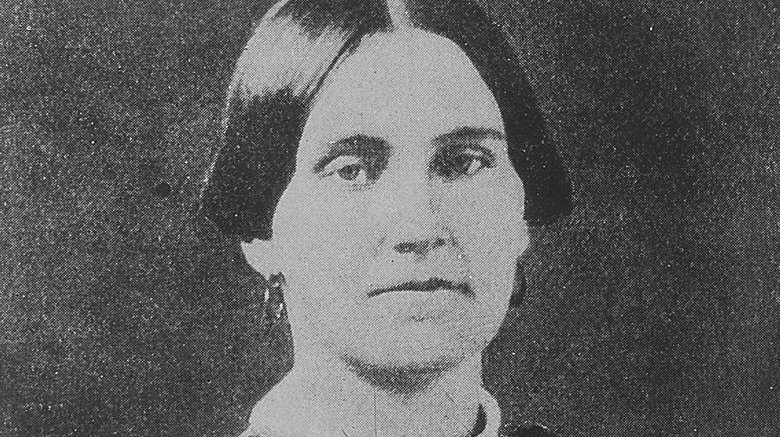

The first woman the government hanged

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt may not be a household name, but she's got two good claims to fame. She's the first woman to ever be convicted of treason in the U.S., and the first woman the federal government executed (via ThoughtCo). A boarding house owner in the mid-19th century, Surratt made the fateful decision to get involved in one of the grandest conspiracies of her time. She was one of the four people who helped John Wilkes Booth pull off the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Surratt's actual role is murky. History says "it is believed" that Booth hatched his assassination scheme in her boarding house, but it's also possible he never told her about it. Regardless, Surratt was linked to Booth via her husband and was arrested along with three other conspirators. They were tried before a military tribunal and all hanged within three months of Lincoln's death. Interestingly, because the other three could be linked to the conspiracy, they were hanged for more concrete charges like murder. Only Mary Surratt was convicted of treason.

Walter Allen becomes West Virginia's fall guy

The Battle of Blair Mountain is the closest the U.S. came to a civil war in the 20th century. In late August 1921, an armed standoff between union miners (above: random union miner) and company strike busters in West Virginia escalated into a full-on battle that lasted over a week, involved machine guns and aerial bombardment, and killed up to 100 people (via History). When the dust settled, the union miners were the ones on the losing side, and West Virginia came down on them, hard.

Over 1,000 miners surrendered to the army, and the state selected a few to absolutely throw the book at. Two were tried with treason, and one guy, a miner named Walter Allen, became the first person since the Civil War era to be convicted of it. According to When Miners March, a history of the uprising, Allen was sentenced to ten years but was allowed to lodge an appeal. He duly did, was granted bail, paid it, and then simply vanished. It's been speculated he no longer trusted the state to deliver justice and so went into hiding. As a result, his conviction was never overturned. His appeal is still on file with the state Supreme Court, presumably on the off chance that he stumbles out of a time machine one day and decides to resume his case.

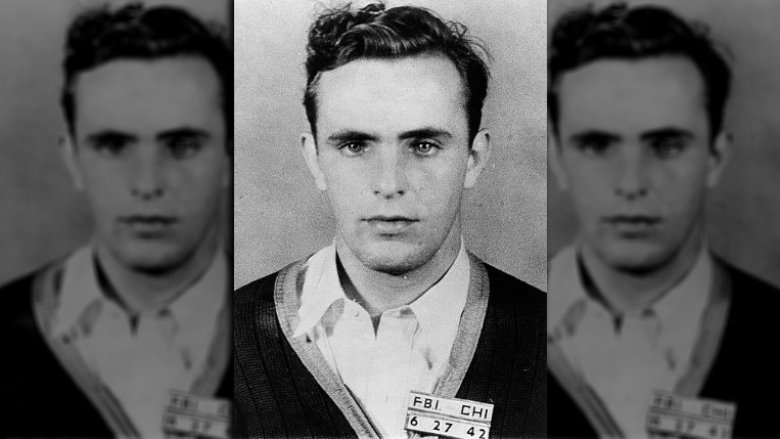

Max Hans Haupt: The sins of the son

Herbert Hans Haupt (above) was a fully paid-up, "blood and soil," "heil the fatherland" Nazi. In 1942 he was one of a group of pro-German defectors who boarded a U-boat to America and landed on the east coast determined to commit sabotage. Given SS training, explosives, and stacks of U.S. dollars, the eight saboteur-defectors were all determined to cause chaos. They were also all bumbling idiots. Before they could carry out a single act of sabotage, all eight were arrested. Shortly after, the six who didn't cooperate with investigators were sent to the electric chair (via History Net).

It wasn't only the saboteurs who were arrested. Two of them had received support from friends and relatives in the U.S. One man, Anthony Cramer, who had unwittingly stored money for the group, was convicted of treason but then had his conviction overturned on appeal. No such luck for Herbert Hans Haupt's dad, Max. Max Hans Haupt's treason conviction was upheld, and he was sentenced to life in prison. He was finally released in 1957 and deported to West Germany.

Martin James Monti defects to the obviously losing side

American history is littered with guys who defected with unbelievable bad timing. Benedict Arnold jumped ship only when the British were already losing like massive losers. Michael Peri attempted to defect to East Germany just ten months before the Berlin Wall fell. And then we have Martin James Monti. A half-German, half-Italian Air Force pilot in World War II, Monti thought the end of Hitler's Reich would mean a global Communist victory. So he stole a plane and defected to fascist Italy in late 1944. Barely nine months later, Italy's last fascist enclave had surrendered and Monti was under arrest.

Incredibly, no one realized he'd defected. They just thought he'd stolen a plane and deserted, so that's what they charged him with. Truman even commuted Monti's sentence in 1946 on the condition he rejoin the Air Force (via History Net). It wasn't until the Washington Post looked into Monti's time in Italy and discovered he'd joined the SS that the truth came out. Monti was arrested again and pleaded guilty to treason in 1949. He was sentenced to 25 years. This time, he served 11 before anyone let him out again.

Douglas Chandler: National Geographic's Nazi

Before he got a job working for Joseph Goebbels, Douglas Chandler was a contributor to National Geographic and was known as the magazine's man in Germany. Since this was Nazi Germany, he was considered an invaluable source of information in the pre-war years. The trouble was, Chandler wasn't exactly unbiased. Throughout the late 1930s, he dripped a steady stream of pro-Nazi propaganda stories into National Geographic. When war finally broke out, he simply ditched his cover and started broadcasting Nazi propaganda openly.

Under the name "Paul Revere," Chandler broadcast a radio show to up to 300,000 Americans nightly. He divided his audience into "Jew haters" and "Jew servers." Chandler supported the Final Solution and told his listeners that America would surely soon follow in Hitler's footsteps. Before the war was even over, the FBI had indicted him for treason and, as soon as victory was declared in Europe, they tracked him to a Bavarian village. Chandler was convicted in 1947 and spent 15 years in prison, one of the longest sentences of any defector. Freed by the JFK administration, he returned to Germany. People have reported meeting him on trains as late as the 1970s. His views hadn't changed one bit.

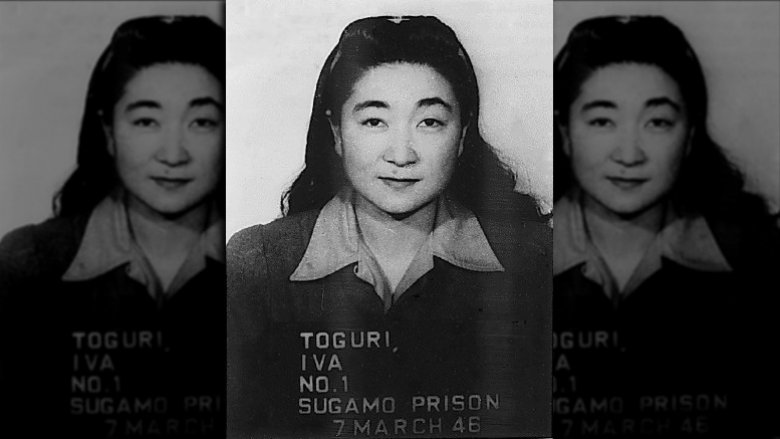

Tokyo Rose's iffy conviction

The surprise Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor sucked for everyone, but it super-sucked for those Americans who happened to be in Japan when the war kicked off. One of those Americans was Iva Toguri d'Aquino, the U.S.-born daughter of Japanese parents, who you might recognize by her more famous nickname: Tokyo Rose. Stuck in wartime Japan, d'Aquino took a job at a Tokyo radio station to make ends meet. Her English broadcasts, built around sappy songs and a little bit of commentary, became notorious for supposedly undermining U.S. troop morale.

The key word there is "supposedly." After the war, d'Aquino tried to return to America but was arrested and tried for treason. Soldiers testified that they'd heard her broadcasting Axis propaganda, and she was convicted. However, the truth was actually much murkier. By the 1970s, it was evident that the soldiers may have either mistaken her for another female English-language propagandist broadcasting out of Tokyo or simply conjured her "subversive" statements from their own battle-scarred psyches. No recordings ever surfaced of her making treasonous statements. As Time notes, the conviction became so confused that President Ford pardoned d'Aquino in 1977. Historians today still can't agree on if she was an actual traitor or just unlucky.

Axis Sally's unlikely end

While Tokyo Rose was trapped in Japan at the outbreak of war, Axis Sally had been sitting comfortably in Germany for years by that point. An Ohio actress who moved to Dresden in 1934, Sally (real named Mildred Gillars) was sympathetic to the Nazi cause and joined the propaganda department after war was declared. Her whole schtick was to play nostalgic American songs and then ponder all the things servicemen's wives might be doing with the neighbor while they were away. (Hint: It wasn't playing cards.) Still, she sometimes made more direct threats, as when she broadcast a chilling warning to Allied soldiers just before the D-Day landings.

It was this last broadcast, incidentally, that got her. U.S. counterintelligence tracked Sally down in Berlin after the war and whisked her back to the States for a treason trial. The D-Day broadcast was the one clear act of treason the courts could agree on, and Axis Sally went down for 12 years. Not that this was the end of her life. After her release, the former Nazi spokeswoman enrolled in a convent back in Ohio, where, according to Britannica she taught French, music and, erm, German.

The forgotten Nazi propagandists

When World War II kicked off, it seemed like all the nutters in American society came crawling out the woodwork and went scuttling off to Berlin's radio stations. Aside from Douglas Chandler, Axis Sally and (debatably) Tokyo Rose, Axis broadcasts were overwhelmed with also-rans and one-offs who briefly poisoned the airwaves, only to be soon forgotten.

One such guy was Robert Henry Best, a former newspaperman who was so anti-Semitic that he felt his best choice was to throw his lot in with the Nazis. As old local papers from his state show, he was convicted of treason after the war and died in prison. He wasn't the only one. Herbert John Burgman was another American turned Nazi-Infowars broadcaster (so just like regular Infowars, then) who was convicted after the war and died in prison. Although their trials were big news at the time, they're both now forgotten.

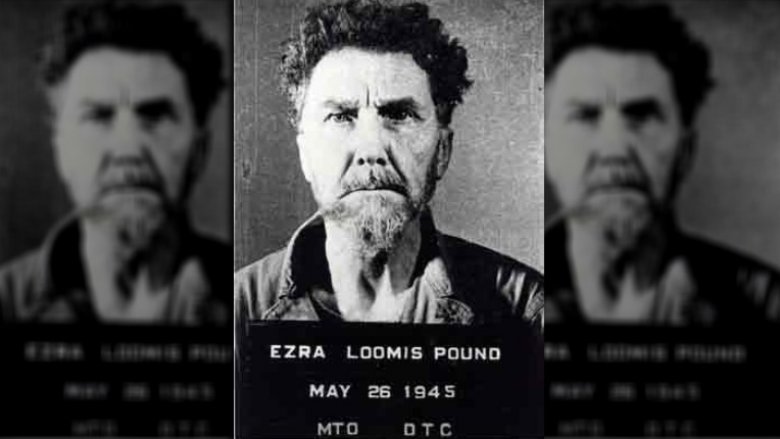

Ironically, one of the traitors we today remember the best was never actually convicted of treason at all. The poet Ezra Pound (above) spent part of the war screaming anti-Semitic propaganda out of the radio before surrendering and being indicted for treason in 1943. However, he was deemed mentally unfit to stand trial and, per History News Network, ended the war being shipped off to a psychiatric hospital. He stayed there for 12 years.

Tomoya Kawakita's enduring record

At time of writing, Tomoya Kawakita has holds a minor, yet notable, place in the U.S. history books. Kawakita remains the last American citizen to be convicted of treason. (Yep, the Rosenbergs came later. And again, nope, they weren't convicted of treason.) Like many others, he was a dual U.S.-Japanese national who had the misfortune to be trapped in Japan when war erupted. Unlike many others, Kawakita managed to take the lemons life had handed him and turn them into particularly sadistic lemonade.

Cornell Law School has Kawakita's Supreme Court case on file, and it makes for some seriously uncomfortable reading. In wartime Japan, Kawakita got a job as a translator, interpreting commands for American POWs being used as slave labor. But rather than being an unwilling participant, Kawakita decided torturing Americans looked seriously fun and joined in the Japanese Army's flagrant war crimes. Thankfully for everyone who believes in justice, one of the men he'd abused recognized Kawakita when he returned to the U.S. in 1946, and the Translator of Death was arrested, convicted of treason, and sentenced to the electric chair. Eisenhower commuted his sentence to life in prison in 1953.