Things About The Civil Rights Movement Your History Teacher Got Wrong

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The civil rights movement is one of the most talked about and discussed social and political movements of the 20th century. And yet, we're grossly misinformed about many aspects of it. Thanks, weirdly vague history books! Why did your teacher not tell you that the FBI shot and killed an innocent young man while he was sleeping? Why did they tell you Rosa Parks was the first woman to refuse to give up her seat to a white person? Was it just a better story to paint MLK and Malcolm X and Good and Bad Guys, one a saint and one a dangerous provocateur? It's pretty crazy to think about all the people and stories that fell through the cracks of time. To quote Hamilton, you have no control who lives, who dies, who tells your story. Here are 12 amazing stories from the civil rights movement that your history teacher definitely forgot to mention.

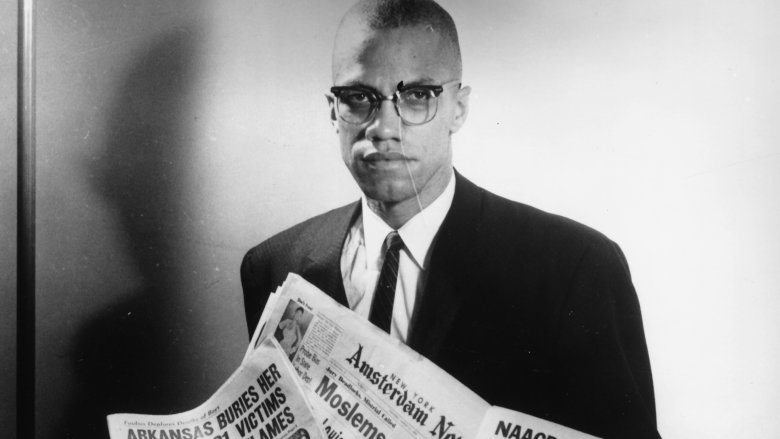

Myth: MLK and Malcolm X were ideological polar opposites

It's commonly thought that Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were on opposite sides of the civil rights playing field. MLK advocated for passive nonresistance, while Malcolm insisted on more violent measures. However, according to historian David Howard-Pitney, "in the last years of their lives, they were starting to move toward one another. ... While Malcolm is moderating from his earlier position, King is becoming more militant."

Interestingly, Malcolm actually began confiding in King's wife, Coretta Scott King. In 1965, the same year he was shot, he spoke "at length" with Coretta "about his personal struggles and expressed an interest in working more closely with the nonviolent movement," MLK stated. This is the civil rights equivalent of, to borrow a line from Ghostbusters, "cats and dogs living together — mass hysteria!" In a pretty historically significant game of telephone, according to King, Malcolm said "if the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King."

If Malcolm X isn't as much the Big Bad Wolf as we're sometimes taught and MLK isn't entirely the peace 'n' love kitten we're told, it makes room for something much more significant than these stereotypes: the truth. Turns out humans are a lot more interesting and dynamic than storybook characters.

Myth: LBJ got civil rights laws started

More than a decade before Lyndon Berg Johnson began signing significant laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Harry Truman took some major risks by defying what many people, including members of his party, thought appropriate.

While he also had a history of racist rhetoric, he surprised everyone by forming the Committee on Civil Rights in 1946. Then, in 1948, he issued an executive order for equal opportunity employment in federal civilian and military services. He also signed legislation that desegregated the U.S. military.

Those are impressive and progressive strides, but Truman never did a complete 180 from his previously racist self. Regarding the sit-Ins of the late 1950s, he said, "If anyone came into my store and tried to stop business I'd throw him out. The Negro should behave himself and show he's a good citizen." You were so close, Harry. You were so close to being remembered as a reformed racist.

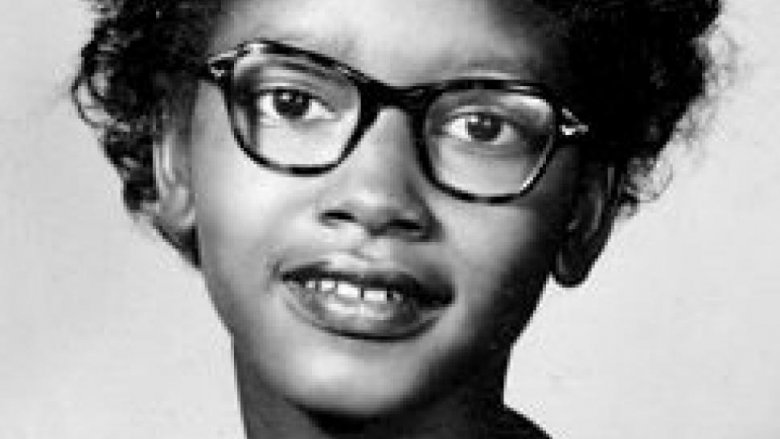

Myth: Rosa Parks was the first woman to refuse to give up her seat on the bus

While Rosa Parks is correctly remembered as an important figure in the civil rights movement, she was not the first woman to refuse to give up her bus seat. Claudette Colvin was a 15-year-old girl who defied the conventions of the time by refusing to move for a white woman on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. She did this a full nine months before Rosa Parks but received little attention in the press.

The incident occured when a white woman wanted Colvin and her three friends to move in order for her to sit down — it was illegal for white people and black people to share a row. Colvin told Teen Vogue, "History had me glued to the seat. Harriet Tubman's hands were pushing down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth's hand were pushing down on the other shoulder."

The police took Colvin to the county jail instead of the juvenile detention center, and she was bailed out by her mother and pastor. Afterward she was "ostracized" by her community, she said. She did, however, get to know Rosa Parks.

Today she is largely forgotten, but there has been a slight resurgence in interest due to an episode of Drunk History and an award-winning book.

Myth: Men and women marched on Washington together

It's been said that well-behaved women rarely make history, but plenty of the rebellious ones don't either. The March on Washington in 1963 was actually two marches — one for men and one for women.

At the main march, Gloria Richardson was only allowed to say "hello" before her microphone was taken away by a man. In fact, only one woman was allowed to speak at the manly march for men. Her speech was 142 words. That woman was Daisy Bates, a journalist and activist who organized the Little Rock Nine in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education — basically an all-around boss lady. Rosa Parks, of all people, was allowed eight words.

One has to wonder what the male organizers were thinking. Would giving too much mic time to women just be a bad look for them? Did they think the women had nothing important to say? Whatever their reasoning, it backfired: The sexist treatment the women endured inspired many of them to band together with white women, sowing the seeds for Second Wave Feminism.

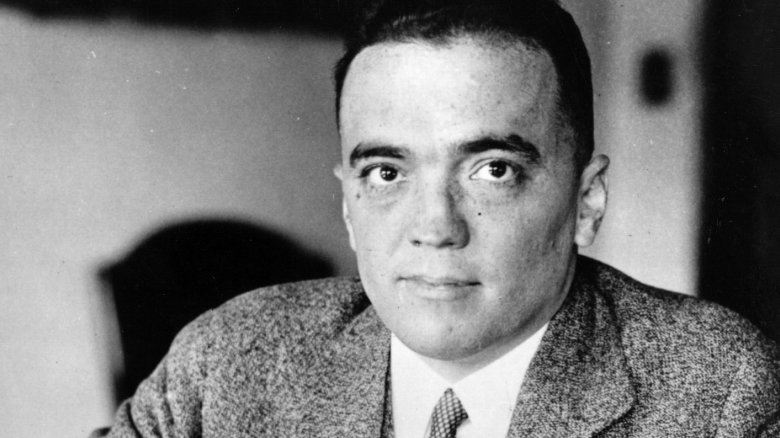

Myth: The government was pretty okay with civil rights

While it's true that in the world of legislation, huge strides toward progress were made in the '60s, the FBI needed some time to catch up to reality. J. Edgar Hoover was something of a mad man, deeply paranoid of anyone he thought to be even vaguely Communist. (He even tapped the phone of John Lennon.) So a year after President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the Nixon-era FBI was getting really freaked out by the Black Panthers.

Hoover was so threatened by the organization that he had an FBI agent infiltrate the organization and pretend to be a bodyguard to a Panther named Fred Hampton. Hampton was a community organizer who became a chapter head of the Panthers at age 20, and the government considered the charismatic leader a threat. So as one does, they had an agent pretend to be his bodyguard, then slip Hampton a powerful sleeping drug, and then have other FBI agents come in and shoot Hampton in his bed.

The agents said the Panthers shot at them, but that wasn't true at all. If the FBI was trying to silence the Black Panthers, this definitely did the opposite. The Panthers, and the American public, were rightfully outraged. It's not every day that the FBI just offs an American citizen.

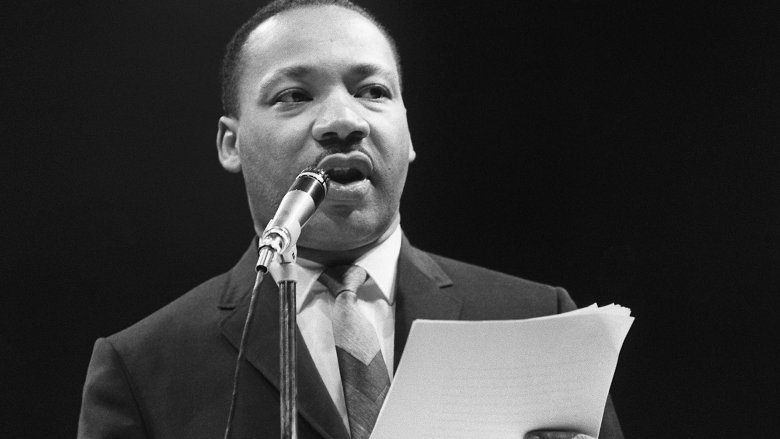

Myth: MLK's biggest concern was dismantling racist laws

History often focuses on the many ways Martin Luther King Jr. influenced laws like the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but his real passion was attending to economic disparity.

In 1967, King said that "after Selma and the Voting Rights Bill, we moved into a new era, which must be an era of revolution. ... In short, we have moved into an era where we are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society."

Thus, the Poor People's Campaign. King planned on staging a protest (not unlike Occupy Wall Street) in which people would camp out on the National Mall in Washington to raise awareness of poverty. They would be protesting for better jobs, homes, and education, and do so by setting up an encampment called Resurrection City. No one had done something so bold before, taking the idea of marching and sit-ins and elevating it to this modern level.

King felt the poor across all ethnic backgrounds could unify and change the world together. And you know, that just might have happened if MLK and campaign supporter Robert Kennedy had not both been killed in 1968.

Myth: The civil rights movement and LGBT movement were separate

It's sometimes thought that these two human rights movements were quite separate issues, but many of the leaders at the forefront of the civil rights movement were also gay. The most prominent would be Bayard Rustin, the architect of the 1963 March on Washington.

Rustin was a close confidant of MLK's and played an important role in introducing him to the passive non-resistance tactics of Gandhi. Rustin was forced to stay semi-closeted throughout the '60s, but eventually lived out and proud. In 1987 he said "Twenty-five, 30 years ago, the barometer of human rights in the United States were black people. That is no longer true. The barometer for judging the character of people in regard to human rights is now those who consider themselves gay, homosexual, lesbian."

Bold words for 1987, but then Rustin was always one to stand up for his beliefs, even when the culture needed time to catch up. Other important LGBT figures of the civil rights movement include James Baldwin, Marsha P. Johnson, Pauli Murray, and Barbara Jordan, among others.

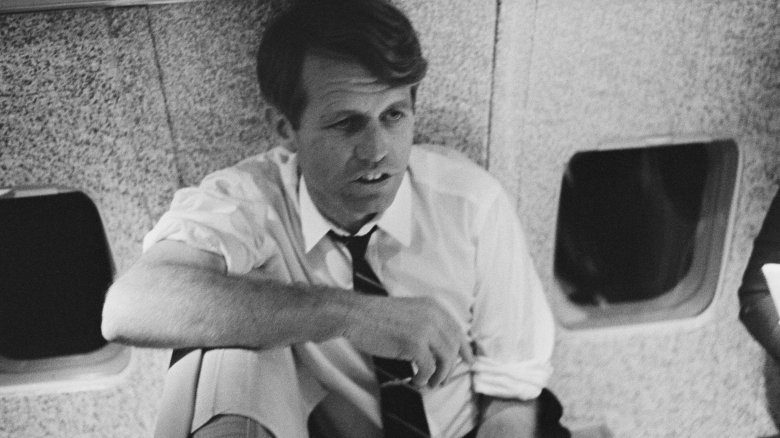

Myth: Robert Kennedy was all about the Freedom Riders

Robert F. Kennedy has a well-documented history of supporting civil rights. His speech immediately following the assassination of MLK is one of the greatest speeches ever, and when he announced his run for president in 1968 he said he would advocate for "policies to close the gaps that now exist between black and white, between rich and poor, between young and old, in this country and around the rest of the world."

Acting as attorney general, Kennedy was instrumental in desegregating interstate travel. Thus, it was a bit off brand when statements from the '60s were released in 2011 that showed he had reservations regarding the Freedom Rides. The statements show a certain hesitancy about those famous bus rides, stating that "a mob asks no questions" and that "a cooling off period" was needed. Robert was aware of the very ugly tensions that ran through the South, and keenly aware of the violence that could occur.

Had he not been shot in 1968, it's humbling to think of what RFK could have done if he'd won the presidency. Instead, we got Tricky Dick. Sometimes life is cosmically unfair.

Myth: Brown v. Board of Education immediately ended segregation in schools

The landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education ordered that schools be desegregated. This was an amazing win for civil rights and for newcomer to the Supreme Court Thurgood Marshall, then a lawyer.

But the South, a century or so behind the times, was none to happy about this new law. They both dragged their feet and put up "massive resistance." This resulted in a second order, Brown v. Board of Education II, which called for desegregation "with all deliberate speed."

The decisions took place in 1954 and 1955 respectively, and yet it wasn't until 1957 that it was truly tested on a national stage. The Little Rock Nine were nine black students who attempted to attend Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Governor Orval Faubus blocked the students, which resulted in President Eisenhower sending federal troops to escort the students into the school. As a result of pressure from the NAACP and bad press due to the Little Rock Nine, Arkansas decided to kind of sort of follow the law and slowly integrate their schools. Not exactly "deliberate speed" — schools in the South weren't really integrated until the '60s.

Myth: The march from Selma to Montgomery was just about voting rights

The march from Selma to Montgomery was one of the most important events of the civil rights movement. The peaceful protesters, led by Martin Luther King, attempted three times to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in an effort to raise awareness of the way black people's voting rights were being suppressed. At the time of the marches, only 2 percent of eligible black voters in Selma were registered to vote.

But, it wasn't just about voting rights. It was actually sparked by the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by an Alabama State Trooper during a peaceful voting rights demonstration. That demonstration had been organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which then organized the Selma march in the wake of Jackson's death.

The march was heavily televised, and Americans watched as the protesters were beaten and tear gassed. The coverage had a huge impact on white Americans' perception of the civil rights protests and was instrumental in swaying public opinion.

Ironically, the bridge in question was named after a Confederate general and KKK Grand Dragon. If you think times have totally changed and we would never condone that kind of thing anymore, well ... there were attempts to rename it in 2015. Alabama was like, nah, let's keep it.

Myth: Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was loved by the government

Thurgood Marshall was the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, a civil rights hero, and all-around awesome guy. So naturally, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI set their radars to "suspicious."

The FBI and Marshall had a tricky relationship. Marshall did feed them information about the NAACP with the belief that he was protecting the NAACP by cooperating with the FBI. Not content with this relationship, Hoover and the gang thought it best to keep tabs on Marshall. Very. Close. Tabs.

They spied on him, which he was aware of, and saw his connection to the National Lawyers Guild as a (very Communist) red flag. They tried in vain to connect Marshall to Communism, finding literally nothing there. So Hoover, behind the back of Marshall, created COINTELPRO, a program specially designated to target the civil rights movement and its leaders.

Eventually, Hoover would endorse Marshall, as he realized they had a mutual love of hating Communists. But his approval of Marshall didn't stop him from moving forward with COINTELPRO, the organization responsible for Fred Hampton's death.

Myth: The most important civil rights moments happened in the South

The South, like the Southern belles it created, wanted to be the center of the civil rights ball. And while much of the action did take place in the South, some incredible moments happened in other parts of the country.

For example, Irene Morgan came before both Rosa Parks and Claudette Colvin when she refused to give up her seat on a bus in Virginia on her way to Maryland. In 1944, aboard a Greyhound, Morgan acted as Parks and Colvin would, with one caveat — she fought back. Morgan kicked one sheriff's deputy in "a very bad place," and when a second deputy came to help arrest her she clawed at him. She would later say she wanted to bite him but that "he was dirty." (It was a Greyhound, after all.) Morgan took her case to the Supreme Court, where she was represented by Thurgood Marshall.

Other non-South moments of note: The first African-American to cast a vote was Thomas Mundy Peterson in New Jersey, and the first college to admit students regardless of race or gender was Ohio's Oberlin College (above). In 1862, Oberlin student Mary Jane Patterson became the first black woman to earn a degree from an American college.