The Untold Truth Of The Monkees

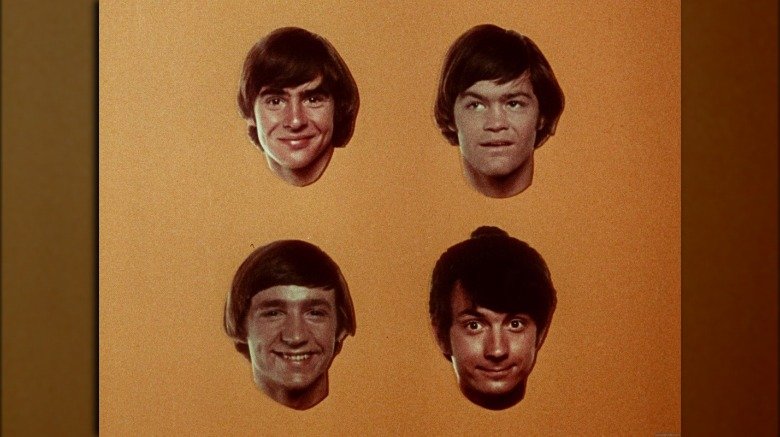

Here they come ... walkin' down the street. Hey. HEY! It's the Monkees! For a very brief period back in the late 1960s — not much more than two years — these wild pop-rockers with the creatively misspelled primate moniker ruled pop culture. From 1966 to 1968, former child stars Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz, along with budding rock stars Peter Tork and Michael Nesmith, competed with the Beatles, Beach Boys, and Rolling Stones and starred in their own innovative, fourth-wall-breaking, music-driven, youth culture-embracing sitcom that won the Emmy Award for Best Comedy Series. Since the Monkees debuted on the scene as an American answer to the boy-band-meets-real-band vibe of British Invasion groups, their songs like "Last Train to Clarksville" and "I'm a Believer" have become rock 'n' roll standards, and still popular enough to pack arenas for the occasional stadium tour. Here's a look back at the spectacular rise and staying power of the Monkees.

Some assembly required

Some bands start in a garage. The Monkees started at Raybert Productions. Run by TV producers Bob Rafelson and Burt Schneider, the company had a deal with Screen Gems to develop a sitcom about a rock band, inspired by the madcap Beatles movies A Hard Day's Night and Help! That idea became The Monkees, about a band of funny guys who also played music. NBC was interested, and so Rafelson and Schneider hired Colgems Records executive Don Kirschner to oversee the musical aspects of the show.

To find the actual Monkees, Rafelson and Schneider placed an ad in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. It read: "Madness!! Auditions. Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers for acting roles in new TV series. Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17-21. Want spirited Ben Frank's types. Have courage to work. Must come down for interview." ("Ben Frank's" was a hip hangout on Hollywood's Sunset Strip.)

While the Monkees have endured some disrespect for being a non-organically-created rock 'n' roll band, that origin was not the initial intent of Rafelson and Schneider. In 1965 and 1966, the Lovin' Spoonful became one of the biggest American rock bands going, landing big hits with "Do You Believe in Magic," "Daydream," and "Summer in the City." Rafelson and Schneider approached that group about starring in a loopy sitcom. The band said no, so producers had to create the Monkees.

Sorry, Charlie Manson

The producers eventually auditioned hundreds of Los Angeles area actors and musicians — 437 to be precise — and found who they were looking for. Among the notable names who tried out: folk singer Stephen Stills; Danny Hutton, just before he joined the enormously successful Three Dog Night; and Paul Williams, who'd go on to be an actor (Smokey and the Bandit) and award-winning songwriter of tunes like "The Rainbow Connection" from The Muppet Movie and Barbra Streisand's "Evergreen" from the 1976 version of A Star is Born.

And contrary to a famous urban legend, there's one notorious individual who did not almost make it into The Monkees. Convicted mass murderer Charles Manson was in prison on a probation violation when auditions took place in 1965. Monkee Micky Dolenz takes credit for starting the rumor. "I just a made a joke. 'Everybody auditioned for The Monkees, Stephen Stills, Paul Williams, and Charlie Manson!'" Dolenz said on Gilbert Gottfried's Amazing Colossal Podcast. "And everybody took it as gospel."

Micky, Mike, Davy, and ... Stephen?

Monkee masters Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider found three band members through that extensive audition process. But the Monkees were a four-piece band. What happened? The fourth slot was supposed to go to seasoned folk musician Stephen Stills. This was after he'd bopped around New York's fruitful Greenwich Village folk scene in the early '60s but before he became the "Stills" in the iconic trio Crosby, Stills & Nash (and sometimes Young). Stills turned down the chance to be a Monkee, but he was kind enough to recommend his potential replacement: Peter Thorkelson, a guy he'd played with in New York who he thought shared the "Nordic look" producers were after. Thorkelson, who adopted the stage name Peter Tork, landed the part of "Peter Tork" while also singing and playing bass in the band. "I was hired to be an actor of a TV show," Tork, who passed away in 2019, explained to Rolling Stone. "The producers did have hopes that something musical would come out of us when they cast the four of us. But if we couldn't have done the music, they would have been all right with us just making the TV show."

The Monkees made TV worth watching in the late '60s

The Monkees debuted in 1966, joining an old-fashioned television universe that looked more like the world in 1956 than it did the present day. Among the hits of the day: Westerns like Bonanza and Daniel Boone, cornball variety shows like The Red Skelton Show and The Lawrence Welk Show, and sitcoms targeted at an older, rural crowd, including The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres, and Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.

And then along came The Monkees, being all wildly creative and low-key revolutionary. As opposed to the stodgier competition, The Monkees popped with vivid color and starred four young men with long(-ish) hair who wore hippie-type clothes and slacked about in their crash pad playing rock 'n' roll music, still a frightening and strange concept to the Greatest Generation. It represented the growing influence of the counterculture.

Moreover, the show chugged along at a frenetic pace, using quick cuts, asides, actors breaking character, camera tricks, and standalone, proto-music videos at the end of each episode to make a series that fully embraced and expressed its rock 'n' roll sensibility.

Blacking out on the set of The Monkees

Not only did the people in charge of the Monkees music prevent the actual Monkees from having much of a voice in the group's artistic direction, but they also prevented them from having a say in the television series they starred in, too. In fact, they were treated like livestock, or worse, extras. When each individual Monkee wasn't needed on set, they were told to report to a black-walled room. From inside, they could do whatever they want — each Monkee had their own corner — so long as they headed back to the soundstage when their assigned call light started blinking.

The Monkees put those experiences — and other, similar ones — into the art. In 1968, the members of the Monkees, largely left to their own devices and with the assistance of screenwriter Jack Nicholson (yes, that Jack Nicholson) made an experimental movie called Head, full of surrealism, symbolism, and general wackiness. It includes some bizarre sequences where Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork, and the rest become trapped in a black box. That was "a metaphor for the Monkees. We used to talk about being in a black box all the time," Dolenz told Mojo. "When we were on tour, especially — but even being on the TV set. We couldn't leave a room or hotel."

Paging Mr. Bob Dobalina

The Monkees made a lot of catchy, fun songs that millions of people enjoyed. Their style: straight-forward, jangly pop rock with the flavor of British bands like the Beatles and Herman's Hermits, exhibited on "Valleri," "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You," "Daydream Believer," and the theme song from The Monkees, which has to be the biggest banger of a sitcom opener ever.

For all their charm, the Monkees aren't regarded as a particularly innovative band. Or were they? In 1967, when the band's handlers finally allowed the members to write their own stuff, The Monkees released Headquarters, which includes a cut called "Zilch." A studio experiment, it involves each Monkee saying nonsensical phrases that were repeated and layered. Peter Tork's line: "Mr. Dobalina, Mr. Bob Dobalina," which he told Mental Floss was something a Monkees associate "actually heard being paged in an airport." Non-singing vocals used to a rhythmic effect? "Zilch" is basically a prehistoric rap song. (Even hip-hop luminary Del Tha Funkee Homosapien thought so, sampling Tork's line for his 1991 hit "Mistadobalina."

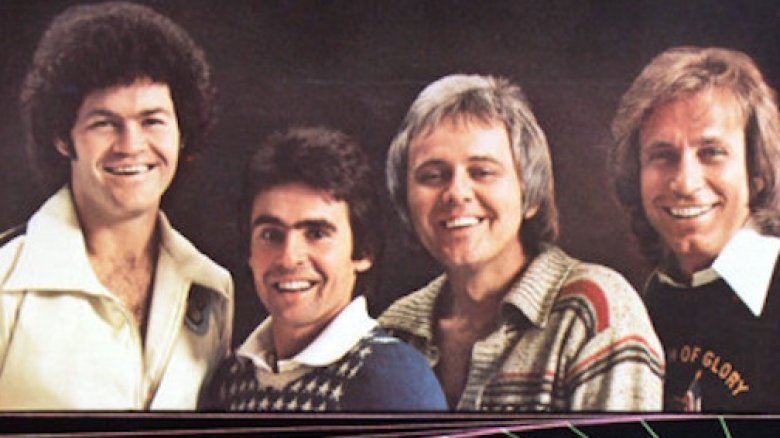

Hey, hey, they're (sort of) the Monkees

Reruns of the kid-friendly The Monkees aired on Saturdays — right after the cartoons finished — on CBS and then ABC in the early '70s. That helped push a 1976 greatest hits album to modest success and also pushed Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz into thinking "reunion!" They couldn't get Peter Tork and Michael Nesmith to join, so Jones and Dolenz instead recruited the two people who were more Monkees than maybe even Tork and Nesmith: Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, who'd written, produced, and performed on many of The Monkees' early songs, including the band's first (and biggest hit), the #1 smash "Last Train to Clarksville."

However, the new group of old collaborators couldn't legally use the name "the Monkees," so they instead recorded an album and hit the road under the boring mouthful Dolenz, Jones, Boyce & Hart. In 1976, the band toured with a show called "The Great Golden Hits of the Monkees — The Guys Who Wrote 'Em and the Guys Who Sang 'Em."

Life after the Monkees

By early 1969, the Monkees began to unravel. Peter Tork left the band, spending $400,000 to buy out the last four years of his contract. The Monkees saw further decimation when Michael Nesmith departed in April 1970. Later that year, the band — then just a duo — recorded its final tracks (for a while) as the Monkees.

Each Monkee then pursued their own path; some were more successful than others. Nesmith formed a country rock group called the First National Band, and scored a #21 hit with the single "Joanne" — making him the only Monkee with a solo smash. He was also an early adopter of music videos, making them for his own projects and creating the compilation show PopClips, which aired on Nickelodeon in 1980. Parent company Warner Cable thought a 24-hour cable network that aired just videos might be a good idea and a year later created MTV, which they asked Nesmith to help develop.

Teen idol-looking Davy Jones (who died in 2012) took the predictable teen idol route. "Rainy Jane" hit the lower reaches of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1971, but this career stage will live on forever, immortalized on an episode of The Brady Bunch in which he sings "Girl" and meets Marcia Brady, president of the Davy Jones Fan Club.

As for Micky Dolenz, the child star of TV's Circus Boy got back into acting. In fact, he was a close second choice to play Fonzie on Happy Days.

When the "M" in MTV stood for "Monkees"

In 1985, concert promoter David Fishof — who'd staged the "Happy Together Tour" featuring '60s relics the Turtles, the Buckinghams, and Gary Lewis & the Playboys — approached Peter Tork about reuniting The Monkees for a 20th anniversary tour in 1986. Together, Fishof and Tork worked over the rest of the band to join up. It took a few attempts to convince Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz, while Michael Nesmith was an even harder "get." He was busy producing movies and TV shows with his company, Pacific Arts Corporation, and agreed to join up when he thought the tour would consist of 10 to 20 dates. He regretfully backed out when "it went from 20 dates to 200 in a matter of weeks," he told Goldmine.

What exploded the tour from a modest, nostalgic affair into one of the most massive musical undertakings of 1986? MTV. In early 1986, the network aired every episode of The Monkees in the form of a weekend marathon. "We've never received such a volume of mail," MTV executive Tom Freston told Rolling Stone. "We were dumbfounded by the whole thing." Suddenly the 20-year-old show was the biggest thing among kids who weren't alive when it first aired. So was the band — almost every date on the Monkees reunion tour sold out, and newly recorded single "That Was Then, This Is Now" hit the top 20.

When the Monkees bit the hand that fed them

In 1986, the Monkees and MTV enjoyed a mutually agreeable relationship: Reruns of the band's old sitcom brought huge ratings to the channel, and the exposure from MTV made the Monkees' reunion tour the can't-miss event of the year. Scarcely a year later, things fell apart.

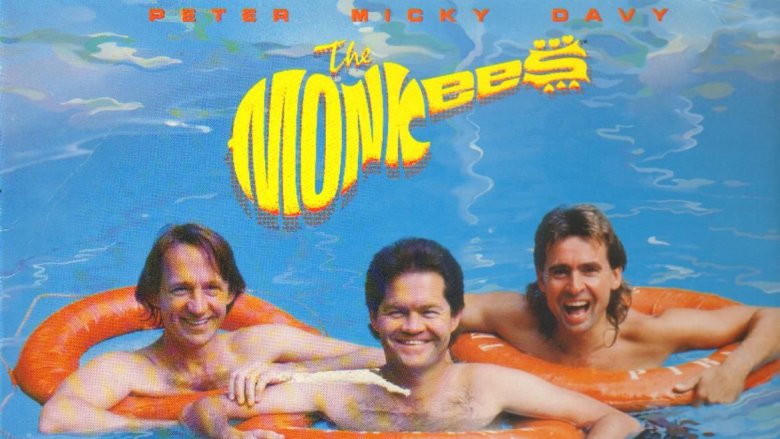

After the success of "That Was Then, This Is Now," the Monkees reconvened (well, everyone except Michael Nesmith) to record a new album, Pool It! The first single was "Heart and Soul," but fans had a hard time finding the video, as MTV refused to air it. According to Monkee Business Fanzine, the Monkees were slated to appear on an MTV Super Bowl special in January 1987. There'd been a miscommunication at some point — the band had no intention of playing the show because it had been booked for another engagement. The executive in charge of the show had only been with the network for a couple of months and didn't understand the unique and fond symbiosis between band and network, so he unceremoniously retaliated by banning "Heart and Soul." It's no coincidence that with the utter lack of promotion from the Monkees' previous champion, "Heart and Soul" faltered at #87 on the singles chart and Pool It! stalled at #72 on the album chart.

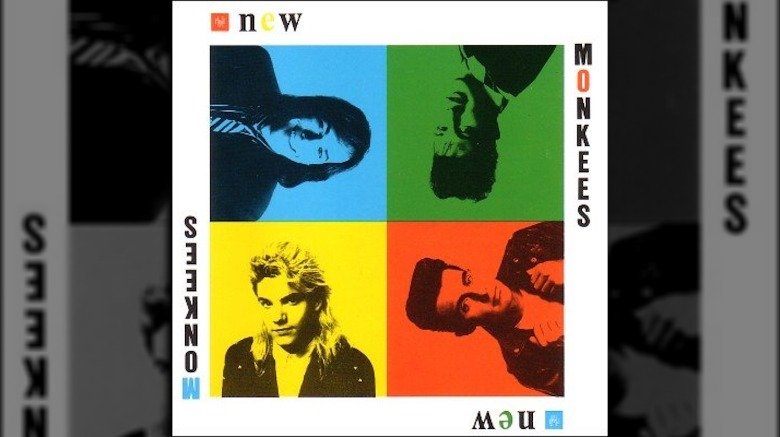

New Monkees? No thanks

Bolstered by the unlikely rebirth and success of a (mostly) reformed Monkees on the charts and on the road, the entertainment world hungered for a full-on Monkees reboot. But rather than get a bunch of dudes in their 40s to run around on camera and record teen-baiting pop songs — because that would've been weird — they just used the Monkees model from the late '60s to launch an entirely new prefabricated band. That meant new members, new songs, a new sitcom ... New Monkees.

To create New Monkees (no "the"), Columbia Records auditioned a number of telegenic young men with musical ability and selected four: Jared Chandler and Larry Saltis on guitar, Dino Kovas on drums, and Marty Ross on bass. (Ross had the most experience in music and TV, having played for a real band called the Wigs and serving on the writing staff of the soap opera The Edge of Night.)

New Monkees was sold into television syndication, and the plot found the struggling rock band living in a gigantic fun house equipped with an on-site diner, a talking computer, and a robot butler. It bombed, canceled after 13 of its planned 22 episodes had aired. On the musical front, one album New Monkees hit stores, promoted with the generically catchy '80s synth-pop single "What I Want." Neither made any sort of chart. The Monkees magic was gone, and New Monkees disappeared from the public consciousness.

Make Monkees, not war

The Monkees may have been designed as a corporate endeavor, but producers left writers with anti-war, hippie-leaning sentiments in charge of the Monkee house. Writers of both The Monkees and the band's songs expressed an anti-Vietnam War sentiment quite a few times ... which is remarkable considering the aggressive censorship of network television in the late 1960s. CBS fired the hosts of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour for too much anti-war content, for example, and yet The Monkees got away with it. According to a show writer who spoke to academic Dr. Roseanne Welch, "The network executives didn't understand what we were saying, so we got away with a lot." The episode "Monkee Mother" opens on the band playing with dominos. Davy says to Peter, "What do you call this game?" Peter replies, "Southeast Asia," a wry send-up of domino theory, the Cold War principle that if Communism were to take hold in one country in the region, the rest would fall like dominos.

And then there's "Last Train to Clarksville," the Monkees hit frequently replayed on the series. It's subtly about a young man drafted into the army, and he doesn't want to go. (In fact, he wonders if he's "ever coming home.") "We couldn't be too direct," said Monkees songwriter Bobby Hart. "We couldn't really make a protest song out of it — we kind of snuck it in."