What Different Religions Say About Marijuana And Its Use

With the rise of both medical and recreational marijuana in recent years, many people have begun reconsidering the plant's role in their lives and society at large. While just a few years ago, it was illegal practically everywhere and even the thought of discussing pot in the open was somewhat taboo, things have undoubtedly changed by today.

For many religious adherents, the idea of voluntarily using marijuana is the complete antithesis of pious and righteous behavior, while others see it as the best way to reach spiritual enlightenment. At the same time, there are countless others who do not see the issue as related, and feel marijuana use and religion are not necessarily intertwined.

Unfortunately, for most people looking for definitive interpretations as to their religion's take on marijuana, it's hard to find a straightforward answer. For the most part, ancient religious texts are mum on the use of marijuana, and they largely do not directly address how it should be handled or looked at. Still, there are many clues that can be used to determine which way a religion leans, and some of the answers might surprise you. From the Baha'i Faith to Taoism, this is what different religions say about marijuana and its use.

Baha'i Faith

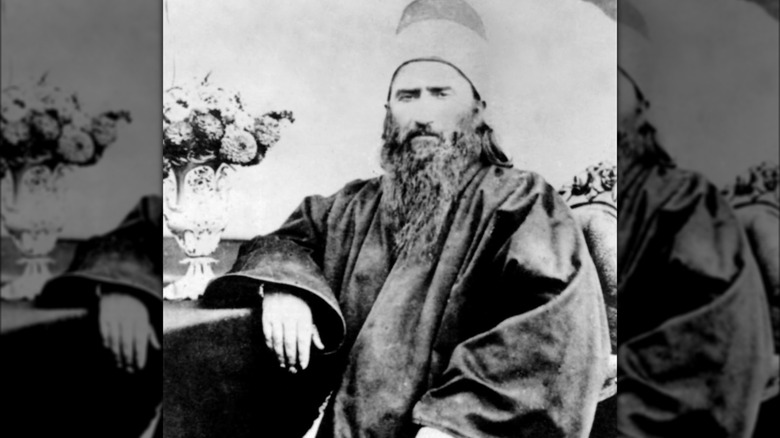

Unlike many religions, the Baha'i Faith is relatively clear about the acceptable use of marijuana and other derivatives like hashish: It's not allowed. The founder of the faith, the Baha'u'llah (pictured above), did not directly address marijuana in the Kitab-i-Aqdas, which is the Baha'i's most holy book of laws. However, he did talk about a prohibition of drugs like opium, as well as "any substance that induceth sluggishness and torpor," which most Baha'i assume to include marijuana. His successor, 'Abdu'l-Baha, reiterated that stance, and even went further to purposefully identify hashish and call it "the worst of all intoxicants."

Like with opium, 'Abdu'l-Baha preached that smoking hash would only cause the user to struggle to connect with God, making it a poor choice for anyone truly seeking spiritual enlightenment. Along with both the Baha'u'llah and Abdu'l-Baha, their next successor in the faith, Shoghi Effendi, also argued that marijuana use was incompatible with living a just life. Like Abdu'l-Baha, Effendi called out hash as a banned drug, comparing it to other substances like peyote or LSD.

For the Baha'i, the only exception to the kibosh on marijuana use is if it is prescribed by a doctor for medical use. That means Baha'i followers might be in luck with medical marijuana, but recreational use is certainly a no-go.

Catholicism

For Catholics wondering about whether or not their religion is compatible with marijuana, for many years it was not so easy to know. The Catholic bible never explicitly talks about marijuana or any of its derivatives, leaving many people to wonder just how Jesus may have felt about the plant — if he indeed had any feelings towards it at all. Yet, since 1992, when the "Catechism of the Catholic Church" was finally approved by Pope John Paul II, Catholics have had their answer, and it's not very pot-friendly.

According to paragraph 2291, the use of any drugs is immoral and should be abstained from. This obviously includes marijuana, and the only exception is for therapeutic use. According to some theologians, like Jesuit Father Peter Ryan of the Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, therapeutic use can include medical marijuana if it is properly prescribed (via Jersey Catholic). But that is not the opinion of all theologians, as another, Dr. William Chavey, argued that the answer is not so clear cut and needs to be studied from a medical standpoint to determine the ethical implications.

Still, pretty much all Catholic theologians would agree though that recreational use is completely off the table under any circumstances. This was made abundantly clear in 2014 by Pope Francis (pictured above), who made a speech at a conference on drug enforcement about his opposition to the legalization of recreational pot.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Considering that even drinking coffee or smoking tobacco is expressly prohibited within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS, colloquially known as Mormonism), it should probably come as little surprise that there is a strict embargo on the use of recreational marijuana for all followers, too. Smoking marijuana is considered to be a violation of the Word of Wisdom, which is essentially the health and dietary code that many LDS followers live by. Part of the LDS justification for not allowing marijuana use is that it can potentially lead to habit forming and addiction.

As for medical marijuana, things get a little bit trickier. The official guidance from the church alludes to its use being permissible, but only through a prescription. Still, if the church's public statements about medical marijuana are taken into account, it's even less straightforward. In 2018, the LDS church said that while it supported the idea of medical marijuana, it was urging its members to vote against Proposition 2, which was the medical marijuana initiative on the ballot.

Yet, Utah did get medical marijuana in 2018, and the LDS church actually worked with politicians to have input on the bill. It would arguably be a stretch to say that the LDS church now actively supports medical marijuana use, but it's also not completely against the idea, either. That doesn't apply at all to recreational use, which is still considered completely different and has no exceptions.

Hinduism

In retrospect, Hinduism is probably one of the most pro-pot religions out there today. Unlike many ancient religions, sacred Hindu texts not only mention the use of marijuana, but it actually played an important part in its history. The Atharvaveda considered cannabis to be a very holy plant that was to be used by anyone looking to purify themselves of sin, sickness, and unhappiness. Even the deity Shiva is said to have used marijuana, which was often consumed in the form of a drink called bhang. Following in Shiva's footsteps, many Hindus continued to use marijuana as a way to gain favor with the Gods and become more connected.

Due to marijuana's extensive history within Hinduism and India, its use continues to be very widespread today. There is actually an exception in the Indian national drug laws that allows for the leaves of cannabis to be sold and consumed as bhang, and the government has a hand in helping regulate its sale around the country. Hindu celebrations like Holi and Shivratri involve copious use of bhang among festival goers, but there are actually three different types of Hindu marijuana. Bhang is the weakest, charas is the strongest, and ganja sits in the middle. Marijuana has always been a very intrinsic part of the Hindu culture, and one that the faith has seemingly embraced wholeheartedly.

Sufism

Sufism is widely known as Islamic mysticism, and while they do worship the Quran, the movement is very ascetic and widely distances itself from the rest of the Islamic faith — and that includes their feelings on marijuana. Beginning in the 12th century, one prominent Sufi leader, Sheikh Haydar of the Haydariyya order, began experimenting with hashish. He was intrigued when he saw some cannabis while out walking, and after ingesting some he seemed to realize it contained stimulating properties.

The use of hashish soon spread amongst the Haydariyya Sufis, even as the Sheikh told his followers to keep a lid on the wonderful new secret. However, once he passed the word got out, and soon the Haydariyya may have been offering marijuana-infused drinks as a substitute for wine, calling it the "Wine of Haydar" (via the University of Victoria's "Drug History Timeline"). The Hadariyya were based in the historical Khorasan area of present-day Iran and Afghanistan, but it's thought that they began to spread hashish south into the greater Islamic world of Syria and even Egypt.

Of all the ways the Sufis use hashish, one of the most popular methods is smoking through a hash pipe, which they call the "nafir-e-vahdat" which means "the trumpet of unity" (via The International Journal on Drug). Many also combine hash and yogurt together in a mix called "dugh-e vahdat" or the "drink of unity." Today, some Sufis continue to use hashish, and there are even Sufi shrines where its use is widespread.

Islam

As the second largest religion in the world with more than 1.8 billion adherents, Islam certainly makes up a large market share of potential religious marijuana users. While the Prophet Muhammad never explicitly mentioned marijuana or hashish in the Quran, it's largely considered to be an outlawed substance. Muhammad did talk about wine and other intoxicants, which he says are banned from being used, and most Islamic scholars apply that same reasoning to marijuana and consider it "haram" or forbidden.

Historically, Persian and Iraqi Muslims first began using hashish sometime in the late 800s, and by the 1,000s it was becoming popular. Nonetheless, Islamic prohibition on cannabis began as early as the 13th century, when the Mamluk Sultan Baybars I made its use punishable by death. Today, many Middle Eastern countries that use Islamic law continue to have extremely strict and severe policies restricting the use of marijuana.

The only exception, according to some Islamic scholars, is medicinal marijuana. In 2018, the Fiqh Council of North America issued a statement on medical marijuana, saying that it was permissible within Islam, but with some caveats. Generally, marijuana-infused medications are allowed, but only if they do not get the user stoned. At the same time, citing the Hanafi and Shafi'i schools of Islamic Law, the Fiqh Council did suggest that some level of intoxication is okay, but only if there is no other alternative and the medicine is proven to work. So Muslims can use marijuana, they just can't get high.

Judaism

Judaism is unique among the Judeo-Christian religions in its relationship with marijuana. According to some interpretations, ancient Jewish scriptures like the Talmud and Hebrew Bible actually reference the cannabis plant. Moreover, many Jewish communities have used marijuana for both religious and medical purposes dating back thousands of years. There is even evidence that ancient Israelites living in the Kingdom of Judah and worshiping at the historic First Temple of Jerusalem consumed marijuana as part of their religious rituals (via the BBC).

Furthermore, while they are not all in agreement, many rabbis consider marijuana to be kosher. In 2013, an Israeli rabbi argued that as long as it was being smoked and not eaten, all marijuana was kosher. Yet, that was modified by a different rabbi, who claimed that only medical marijuana was kosher. In January 2016, OU Kosher, one of the biggest purveyors of kosher products worldwide, began certifying some medical marijuana products as kosher. Some interpretations hold that marijuana is part of a group of foods known as kitniyot that are banned among Ashkenazi Jews on Passover, but a ruling in 2016 by a respected ultra-Orthodox rabbi claimed medical marijuana was exempted from the prohibition and allowed to be used or eaten.

In Israel, recreational marijuana has long been illegal, but medical marijuana became permissible in the 1990s. Generally, rabbis have held that medicinal use is okay, especially if it is used for pain reduction, while recreational use is not.

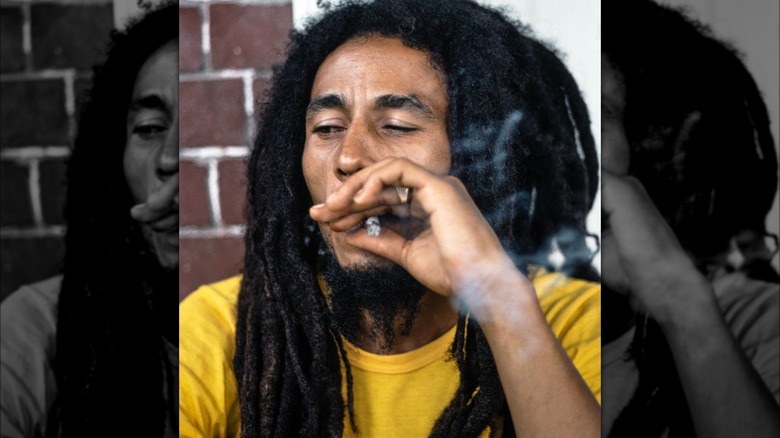

Rastafarianism

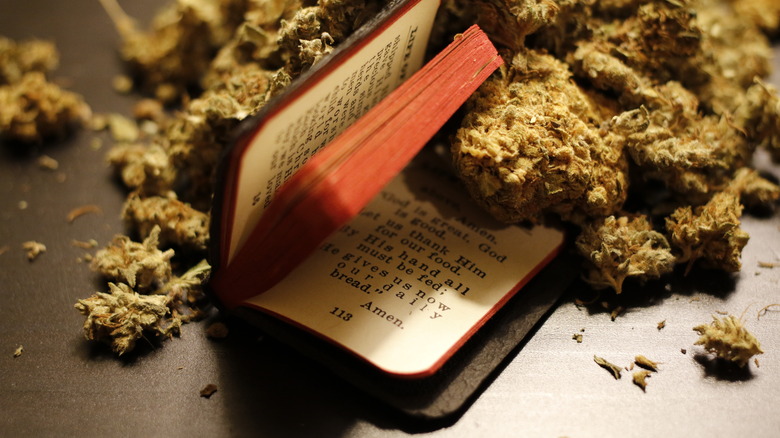

Of all the modern religions today, Rastafarianism probably has the most visible connection with marijuana. For Rastas, marijuana, which they often refer to as ganja, is one of the most important herbs on the planet. They interpret the bible as referencing marijuana multiple times, and many Rastas see smoking ganja as akin to taking the Christian Eucharist. Rastas don't just smoke marijuana, though, as they also cook with it and use it as medicine. The use of marijuana among the Rastafari is highly spiritual and they believe it helps to cleanse and clear the mind.

It's thought that marijuana was introduced to Rastas in the 19th century by Hindu Indian laborers who used ganja as part of their own religious worship. Within Rastafarianism, marijuana is revered because of its ability to encourage and stimulate peace and togetherness in the community, and they often use it for meditation. It is considered to help reveal one's true inner self, and smoking is often done in a large group setting where many members participate together. Sometimes, they will say a prayer while preparing the marijuana to be smoked, and the most popular ways of smoking are as a marijuana cigar or through a water pipe known as a chalice, kutchie, chillum, or steamer.

After smoking, practitioners will typically engage in reasoning sessions, where they attempt to reach a higher mental clarity together through conversation. For Rastas, marijuana is definitely no joke, and it's a sacrament rather than a recreational drug.

Taoism

Taoism and marijuana have been linked together for thousands of years. At first, though, the Taoists are thought to have rejected the cannabis plant when they came into contact with it in 600 B.C. (via Mitchell Earleywine in "Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence"). Yet, for whatever reason that appears to have changed about seven centuries later, and by A.D. 100 they had apparently discovered its psychoactive properties.

It's unclear exactly how they used the marijuana, which may have brought on hallucinations, as ancient literature points to them ingesting cannabis seeds — which are notoriously low in THC. In order to be high enough to see hallucinations, they would have needed to get a lot of THC in their system, which they probably could not have done from eating seeds alone, suggesting they may have found a way to smoke or otherwise ingest the marijuana.

Additionally, there is also something of a cannabis deity among Taoists known as Magu. Magu, which can be translated as hemp, is identified among ancient Taoist texts with the cannabis plant's healing properties, as well as Mount Tai in China, where it's reported that a lot of cannabis plants naturally grow. It's unclear how many religions have cannabis deities, but Magu is most likely unique in that respect, and she certainly adds to the Taoist-cannabis intrigue.

Sikhism

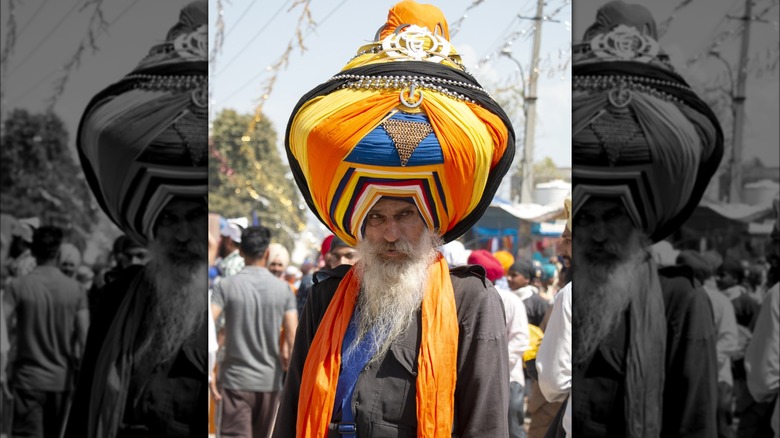

While most Sikhs do not partake, marijuana is very prevalent within the Nihang Sikh community. The Nihangs, also known as Akalis or "the immortals," are a group of Sikh warriors who traditionally helped fight off invaders from Afghanistan and the Mughal Empire. According to The Tribune India, the Nihangs started using marijuana both for medicinal and therapeutic purposes while they were fighting. It helped them to heal from injuries, likely by reducing pain and also made the warriors calmer when they were heading into battle.

The Nihangs call their marijuana concoction "bhang," "sukha," "Shaheedi Degh," or "panj pattey," and it consists of cannabis leaves that are eaten. However, the Nihangs martial era is well behind them and they have not been fighting battles for almost 175 years, so the continued use of marijuana among them is becoming more controversial. Some Nihang groups have started to make their members stop using marijuana, which is somewhat of a rejection of their stance just a few decades ago, but its contemporary consumption is thought to be somewhat inappropriate since it's not being used during battle.

Furthermore, the official Sikh code of conduct, or Sikh Rehat Maryada, bans marijuana from being used by followers because it is intoxicating, and the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak, counseled against using substances like marijuana. With the new restrictions on the Nihangs' use, it appears as if marijuana and Sikhism might be headed for a permanent split, but only time will tell.

Santa Muerte

The cult of Santa Muerte is one of the most mysterious and misunderstood in modern times. Nonetheless, what is widely known is that it has a very close relationship with marijuana. The cult actually dates back centuries, but only more recently has started to become popular, largely due to its association with deadly drug trafficking narcos. There are no specific sacred Santa Muerte religious texts that talk about marijuana, but there are many temples and shrines, and lots of them are connected with pot.

Not all followers of Santa Muerte consume marijuana, but those who do are known for using its various forms to interact with the deity. Often, they will pray to Santa Muerte and blow marijuana smoke on a shrine to ensure the prayer will come true. This is probably the most visible facet of Santa Muerte's connection with marijuana, and it shows that the drug is truly an integral part of the faith for many followers.

In addition to marijuana, alcohol, and other narcotics are also used by worshippers to connect with the Santa Muerte deity. Importantly, not all Santa Muerte followers use marijuana or other intoxicants, but for many, the two are divinely linked.

Buddhism

Buddhism has been pretty clear both then and now that marijuana use, at least for recreational purposes, is forbidden. While Buddha himself did not preach on marijuana, there are Five Precepts of Buddhism, which basically serve as a moral guide for how a Buddhist should live their life. The fifth of the precepts says that one should "Refrain from intoxicants that cloud the mind," which seems like a very clear reference that would apply to marijuana (via the BBC). Interestingly, it has been suggested that Buddha may have consumed the hemp plant during his travels, though it is key to keep in mind that hemp does not have psychoactive properties (via Paul Carus in "The Gospel of Buddha According to Old Records").

In modern times, Buddhist leaders have continued to subscribe to a ban on marijuana use. In an interview in 2014 in Time, the Dalai Lama was vehemently against the use of marijuana for any recreational purposes, calling it "poison." He did express some acceptance of its use for medical grounds but also suggested that it could lead to brain damage, though he may have been referring to more spiritual than physical matters.

Similarly, in 2022, the National Office of Buddhism in Thailand prohibited Buddhist monks from using marijuana, even though the country had just made it legal (per The Nation Thailand). Likewise, monks were also not allowed to grow marijuana at their temples or monasteries, and could only use it with a doctor's prescription.

Shinto

Shintoism is one of Japan's oldest faiths, and though it does not have a specific written doctrine, marijuana use has been a big part of the religion for many followers. According to Jon Mitchell in The Asia-Pacific Journal, Shinto priests and followers have been using marijuana for a long time for its purifying abilities. Priests are said to have used marijuana to ward off evil spirits, often by waving it in the air — though it's hazy on whether or not the marijuana is lit while they are doing this. Historically, it also played a role in many weddings, as brides apparently wore cannabis veils during their nuptials.

Mitchell also claims that the Ise Jingu shrine, which is one of the most important Shinto destinations in the country, even references marijuana through annual ceremonies known as "taima," which means cannabis in Japanese. The Ise Jingu is located in the Mie Prefecture, which is also where a group known as the Shinto Association operates. In 2018, the Shinto group recently got a license to start growing low-THC hemp (via High Times). The Shinto association can grow cannabis for two shrines in the prefecture, neither of which is the Ise Jingu, and they use it in spiritual rituals.

Santo Daime

The religion of Santo Daime from Brazil is relatively new, and its connection with marijuana runs very deep for some. Santo Daime first sprung up in the early 1900s in Brazil after being founded by a man named Raimundo Irineu Serra, and it combines widespread elements ranging from folk Catholicism to Indian shamanism. While much of the religion is based around the use of the psychedelic concoction known as ayahuasca, which is what Santo Daime means, marijuana is also prevalent as a spiritual guide, but only for some followers known as Daimistas.

Daimistas refer to cannabis as Santa Maria, but it's only one group of them who are known to use it widely. In the 1970s, Daimistas under Padrinho Sebastiao, who was a friend of Serra's before his 1971 death, split off from the larger Santo Daime sect. They soon began using marijuana as a sacrament after a follower introduced it to him. It's suspected that Serra may have also used marijuana, but his followers dispute this. When Sebastiao realized the healing properties of marijuana, he started calling it Santa Maria and combining it with Santo Daime in religious ceremonies to help him have deeper and more spiritual visions.

However, among the rest of Santo Daime's followers, they largely view marijuana as a drug and do not ascribe to it the same holiness that Sebastiao's sect does. This makes Sebastiao's group somewhat outsiders and their affinity for marijuana polarizing among Santo Daime worshippers.

[Image by Tonelada via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is one of the world's oldest religions in the Middle East, and there is some evidence to suggest that marijuana played a role in many ancient Zoroastrian practices. The Zend Avesta, which is the most sacred book of Zoroastrianism, actually talks about marijuana in one of the volumes known as the Vendidad. The Vendidad refers to cannabis as bhang, a common name for the drug in Asia, and explicitly refers to it as a "good narcotic" (via Science Advances). By calling it a narcotic, that seems to imply that the Zoroastrians were using it for psychoactive purposes, but that is not definitive.

Another area of the Zend Avesta that may reference marijuana is its mention of Haoma or sauma, which it calls a divine plant. One scholar, B.L. Mukherjee, suggested that sauma could be translated as cannabis, but others disputed this notion, with some saying sauma is actually an allusion to hallucinogenic mushrooms, instead (via Encyclopedia Iranica).

Outside of actual scriptural references, it is also thought that Zoroastrians may have found a way to incorporate marijuana into burial rituals, and there is also evidence that they used it for spiritual purposes, too. The latter would again point to them having knowledge of its psychoactive effects, but that is just speculation.

Oklevueha Native American Church

For members of the Oklevueha Native American Church (ONAC), cannabis is not just a drug, it is an incredibly important sacrament. ONAC is a Native American religious tradition that uses natural substances like cannabis, psilocybin (hallucinogenic mushrooms), ayahuasca, and peyote in order to gain a higher spiritual enlightenment. The founders of the church hold ceremonies where they use marijuana as a medicine, including pipe ceremonies where the medicine is smoked. Importantly, they are one of the few American groups where it's actually legal for them to do so.

The ONAC is a federally recognized and registered Native American tribe that is exempted from laws that make marijuana federally illegal. Many members have official government ID cards that basically give them a license to carry plants and other natural substances that would otherwise be deemed illegal. According to their official guidelines on their website, members are allowed to have up to two ounces of marijuana for personal use, and they even have a specific guide on how to cultivate it.

However, that has not stopped the police from arresting some ONAC members on drug charges, even if law enforcement's record of victories in the area is murky. Still, ONAC remains committed to using marijuana as a spiritual and medical sacrament, regardless of its legal position.