People Executed For Murder Who Definitely Didn't Do It

Supreme court justice Antonin Scalia once infamously implied that innocent people are never executed in the United States. "If such an event had occurred in recent years," he wrote, "we would not have to hunt for it; the innocent's name would be shouted from the rooftops by the abolition lobby." That would be an adorable example how one can have way too much faith in a flawed system of justice, if so many lives weren't at stake.

In fact, wrongful executions are well documented in this country and in others, and the terrifying truth is that anyone who's in the wrong place at the wrong time is vulnerable. Wrongful convictions can happen because witnesses identify the wrong person, or because the police coerce a confession, or because evidence is ignored, or even because a public defender is overworked.

How can you protect yourself from wrongful conviction and execution? Mostly just don't interact with other humans. Of course, that will only get you so far when your neighbor decides that the weird guy who doesn't interact with other humans seems guilty as hell.

Anyway, just in case you're still skeptical, here are a few awful examples of people throughout history — in some cases recent history — who actually died for crimes that they definitely did not commit.

Executed for murdering someone who wasn't actually dead

Any prosecutor can tell you that capital crimes are especially difficult to prosecute if you can't produce a murder victim. There certainly have been examples of successful convictions without a body, but generally speaking, you need pretty irrefutable evidence to pull off that kind of conviction.

Yet somehow, this happened. Granted, this was in the UK in the 1600s, back when people could be convicted of witchcraft by getting thrown in a lake. If this happened today, probably no one would be executed. Probably.

Anyway, here's what happened according to the book Miscarriages of Justice by Brent E. Turvey and Craig M. Cooley: William Harrison went out and never came back. The next day, his hat and collar were found in "a hacked and bloody state." Suspicion almost immediately fell on his 14-year-old servant, John Perry, who was taken into custody and eventually not only confessed to killing Harrison, but also implicated his own parents. All three were hanged for the crime.

Then, two years later, Harrison showed up with a story about how he'd been attacked, abducted, and pressed into service on board a ship. So, not dead.

What happened? Why did John Perry confess to a crime he clearly didn't commit? We don't know exactly what Perry said to investigators, but we do know that even modern interrogation techniques can produce false confessions, because interrogation sucks and some people will say anything to make it stop. Especially, it seems, 14-year-old kids.

Executed for the crime of living in the same building as a serial killer

In 1948, a man named Timothy Evans showed up at a Welsh police station and confessed to the accidental killing of his wife. According to the BBC, Evans told police that his wife, Beryl, had died from an abortifacient.

Here's what really happened: Evans told his neighbor, John Christie, that his wife (who was pregnant with a second child they couldn't afford) needed an abortion. Christie, who was already a prolific serial killer, perked up and said (we're paraphrasing), "Oh, I totally know how to do abortions!" So, Evans placed his wife and their infant daughter in Christie's care, and then Christie killed both of them. Christie then told Evans that the abortion had gone wrong, and that Evans' daughter was being looked after by a couple of good Samaritans. Evans, who believed Christie's story, lied to police to protect him.

Police later found both bodies and coerced a confession out of Evans, who was clearly distraught and also had an IQ of around 70, which made it pretty easy to manipulate him. He was tried and found guilty of both murders, and in March of 1950 he was hanged for the crimes.

Three years later, police found six bodies in John Christie's home, one of which was his own wife. He readily confessed to their murders, and also admitted to killing Beryl Evans. Christie was also hanged, but a fat lot of good that did as far as Timothy Evans was concerned.

Executed for the crime of not being able to speak English

Today she's a Texas legend, but that wouldn't have been much consolation to her as she was being led out to the tallest oak tree for her execution. Chipita Rodriguez was accused of murdering a horse trader named John Savage with an axe.

Depending on who you ask, Chipita was either 63 or 90 years old at the time, so it would have hardly been a trivial thing for her to murder an adult man with an axe, but never mind. According to the Texas State Historical Association, the motive was supposedly the $600 in gold he was carrying, although the gold was later found north of where Savage's body had been found, so if Chipita was a gold thief she wasn't a very good one.

Savage wasn't exactly making friends the night he was killed — he was reportedly at the local saloon bragging to Confederates that he'd just sold horses to the Union Army. In other words, Chipita wasn't the only one with a motive, if you can even call stealing gold and forgetting to take it home with you a motive.

Chipita didn't speak much (if any) English, so she couldn't really defend herself against the accusations. That made it pretty easy for the law to conclude she was guilty. Happily for Chipita, a judge decided that the evidence didn't add up and exonerated her. Unhappily for Chipita, that didn't happen until 122 years after her death.

Executed for being too dumb to know he was about to be executed

Joe Arridy was developmentally disabled, and he had the mental age of a six year old. That makes his execution especially cruel, and when you figure in the part where he didn't actually commit the crime, well, "cruel" kind of becomes an understatement.

According to Westword, Arridy was accused of murdering a 15-year-old girl in Pueblo, Colorado in August of 1936, mostly because he had the handy habit of agreeing to just about any question he was asked. Which is pretty great when you need someone to pin a murder on.

The problem, though, was that another suspect was already in custody. Frank Aguilar fit the description of the murderer, and he'd also been caught doing some murderish sorts of things, like hanging around at the victim's funeral and having a second look at her body inside the casket. He also knew the victim's family, and appeared to be a collector of newspaper clippings on the topic of sex crimes. He also owned a hatchet that had marks which seemed to match the marks on the body.

That's okay, though, because Carroll just made Arridy an accomplice, and both men were tried, found guilty and executed, despite there being almost no evidence connecting Arridy to the crime. And to make a sad story even sadder, Arridy had such a childlike mind that he went to the gas chamber without ever really understanding that he was going to die there.

Executed for sleeping in a car with a murderer, and also his head caught on fire

Jesse Tafero, his girlfriend, and a man named Walter Rhodes were sleeping in their car at a Florida rest stop when they were approached by a highway patrolman and his friend. The incident somehow went terribly wrong, and both the highway patrolman and his friend were shot dead.

The trio were eventually apprehended, and Rhodes agreed to plea to a lesser charge in exchange for implicating Tafero and Tafero's girlfriend, Sonia Jacobs. Tafero and Jacobs were both convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to death. (Jacobs' sentence was later overturned).

The evidence didn't support Rhodes' version of the story, though. Gunpowder tests suggested that Rhodes had fired the gun, and Rhodes changed his testimony three times. Also, an eyewitness said that Tafero had been detained by the officer outside the car at the time of the killings.

As if all of that didn't already suck very much, History says that Tafero's execution went horribly, horribly wrong. An electric chair malfunction caused flames to "leap from his head." Witnesses claimed he was still breathing afterwards, which seems to imply an especially sucky death. Tafero's death did prompt renewed debate about the use of the electric chair, and was at least partly responsible for the move towards lethal injection. That's great, but it's too bad that one innocent guy had to die in such a horrible way before someone finally decided things had to change.

Executed for being rich enough to afford a good lawyer

In 1913, 73-year-old Civil war veteran John Q. Lewis was killed in his home. According to CNN, the investigation first focused on the 22-year-old married black woman Lewis was having an affair with, but for some reason police abandoned that lead. There was speculation that they just didn't want that kind of scandal staining their otherwise squeaky-clean courts, which seems really weird, because without scandal, what would courts even do? But anyway, police moved on to another suspect, who then pointed to Thomas and Meeks Griffin.

What's really weird about this story is that the Griffin brothers were black, and it was South Carolina in 1913. But instead of calling for blood, the community rallied around the men. That was so odd that one legal historian remarked that "only the most profound sense of injustice would have led so many white leaders of the community and ordinary white citizens to publicly support blacks convicted of murdering a white man."

Even more damning, the man who fingered the Griffin brothers later said he'd done it because he thought they were wealthy enough to pay for good lawyers who would help them get acquitted. But alas, no — both men died in the electric chair in 1915. A century later, their grand-nephew appealed to the South Carolina courts to have their conviction overturned. He succeeded, but you know, they were still dead.

Executed for failure to confess to a crime he didn't commit

Scalia made his infamous "shouted from the rooftop" remarks in 2006, which means he either missed or just totally ignored the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who'd been executed in Texas just two years before for a crime he didn't commit.

Willingham was convicted of the murders of his three children, who died in a house fire in 1991. Investigators claimed there were clear signs that someone had poured accelerant all over the children's bedrooms, and since Willingham had escaped the home unscathed, they concluded it must have been him.

But according to The New Yorker, later investigations showed that the burn patterns in the home weren't necessarily consistent with arson — in fact, a later recreation of the fire showed that no accelerant was necessary to produce those burn patterns. They could have happened just as a result of a piece of furniture catching fire. Also, no traces of accelerant were ever found in the home, except on the front porch... which was where the family barbecued, so there was that.

When Willingham was offered a life sentence in exchange for a guilty plea, he refused. "I ain't gonna plead to something I didn't do, especially killing my own kids," he said. None of that was good enough for the state, though, which denied his application for clemency. He was executed in 2004. Unfortunately, despite the efforts of the Innocence Project, he has yet to be formally exonerated.

Executed for having hair that sort of resembled crime scene hair

In 1989, Claude Jones was arrested in Texas for the murder of liquor store clerk Allen Hilzendager. There were no witnesses to the crime apart from two people who were repairing a car across the street. Neither of them was able to identify the perpetrator. That didn't stop police from arresting Claude Jones, mostly based on a fragment of hair found at the scene of the crime.

According to the Innocence Project, witnesses could place a beige Ford truck owned by one of Jones' friends at the scene of the crime. Jones was convicted based on that small hair sample, which prosecutors said was consistent with Jones' hair. He was executed for the crime in 2000.

Years later, the Innocence Project requested DNA testing of the hair sample, and Texas refused. What's more, they were evidently planning to destroy the hair sample until a judge stepped in and said, "Uh, you can't do that." Nothing says "our conclusions were sound" like deliberately destroying the evidence that someone could have used to validate your sound conclusions.

Besides the hair, the case was a whole mess of people changing stories and accomplices plea bargaining in exchange for pointing the finger away from themselves. But the 2010 DNA test was what eventually exonerated Jones — a decade too late, but that's better than nothing... isn't it?

Executed for having the same first name as the guy who actually committed the crime

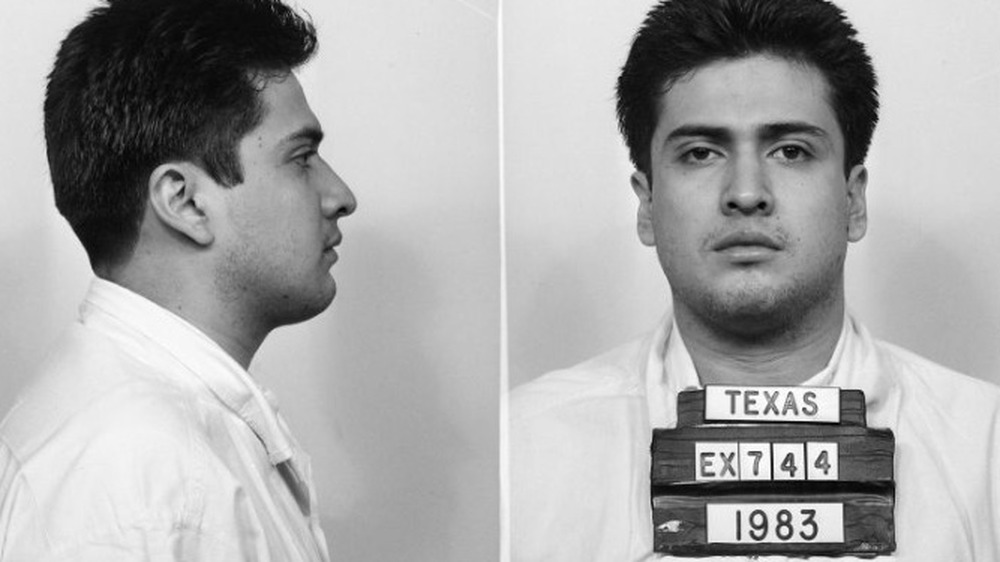

In 1989, Carlos DeLuna was executed in Texas, because Texas. DeLuna had the misfortune of looking a lot like another guy named Carlos, who probably did commit the crime.

According to The Guardian, DeLuna was arrested for the murder of a woman named Wanda Lopez. DeLuna professed his innocence throughout his trial and subsequent residence on death row, which is not in itself unusual for someone who has been convicted of murder (just about every one of them will at some point utter the words "I'm innocent"). But DeLuna's protestations were different, because he also pointed to the man who did do it — another dude named Carlos. Carlos Hernandez didn't just have the same first name as DeLuna, he was practically the guy's doppelganger. They looked so much alike that DeLuna's sister actually couldn't pick out her brother from a series of photos of the two men.

Carlos the Other, as it turned out, had a long history of violence and was even found lurking near the crime scene with a knife just a few days before the murder. He later bragged to friends that he'd killed Wanda Lopez, and his "tocayo" had taken the fall for it. But somehow during the trial, prosecutors convinced the jury that Carlos Hernandez didn't even exist. So in 1989, DeLuna was executed, and Texas dusted off its hands yet again. Yay, Texas.

Executed for being a black kid near the scene of a crime

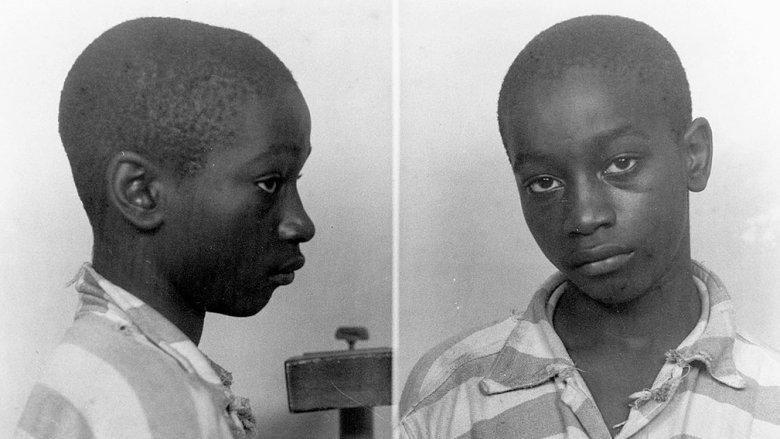

The youngest person ever executed for murder in the United States was a 14-year-old black kid named George Stinney, who died in a South Carolina electric chair in 1944.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Stinney was playing in his front yard with his sister when two white girls approached and asked him if he knew where they could go to pick some flowers. The two girls disappeared later that day and were found dead in a ditch the next morning.

Unfortunately for Stinney, he'd mentioned to someone that he saw the girls just before their disappearance. For prosecutors, that was as good as a confession. They arrested him and grilled him for hours without the presence of either parent or an attorney. The sheriff who interrogated him claimed that the boy admitted to the crime, but there was no signed confession, and anyway, we all know what hours of interrogation can do to a 14-year-old kid.

Stinney was convicted without any evidence, and his court-appointed attorney didn't bother to call any witnesses. His fate was decided in 10 minutes by an all-white jury. He was such a small kid that the electric chair's straps didn't fit him and he had to sit on a book so he could be properly hooked up to the machine. Still, it took 70 years for a judge to declare that Stinney had been deprived of due process and wrongfully executed.

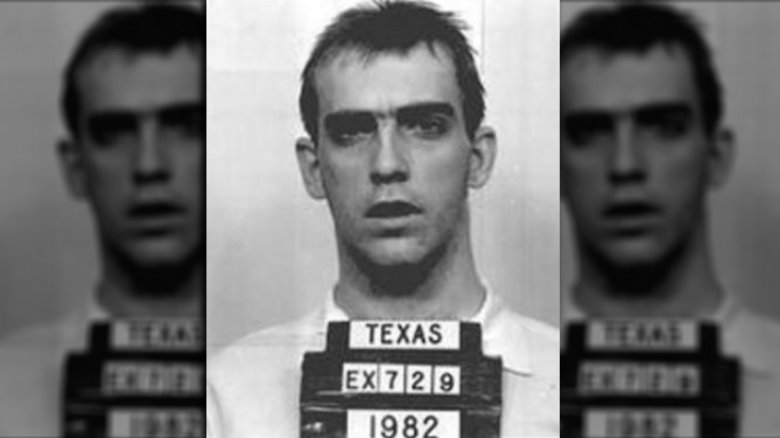

Executed for being in Texas

In 1992, Johnny Frank Garrett was executed in — where else — Texas for the rape and murder of a 72-year-old nun. His last words were, "I'd like to thank my family for loving me and taking care of me. And the rest of the world can kiss my everloving ass, because I'm innocent."

Garrett was only 17 at the time of the murder, and he was probably also developmentally disabled. Executing people with severe intellectual disabilities was ruled unconstitutional in 2002 — a decade too late for Garrett, though there was also the problem that he didn't actually commit the crime.

As in so many of these cases, police jumped on the Johnny Frank Garrett train pretty early on and refused to jump off again when it became clear that they had the wrong guy. The nun's murder was actually one of two similar murders of elderly women that happened around the same time. A man named Leoncio Rueda Perez was convicted of the second crime. According to Grave Injustice by Richard J. Stack, Rueda also admitted to killing the nun, but he entered into a plea bargain in which he would confess to the second murder in exchange for avoiding the death penalty. That suited the state of Texas just fine, since it meant they didn't have to revisit the potentially embarrassing wrongful execution of Johnny Frank Garrett.

So, that's another check in the "wrongfully executed in Texas" column. What did Scalia say about shouting things from the rooftops again?