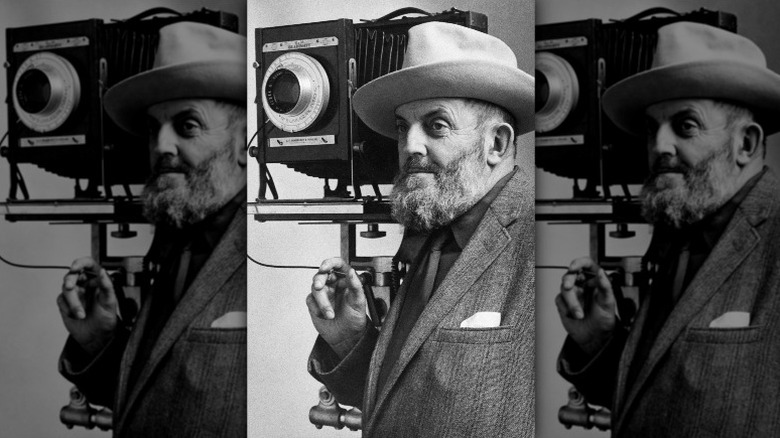

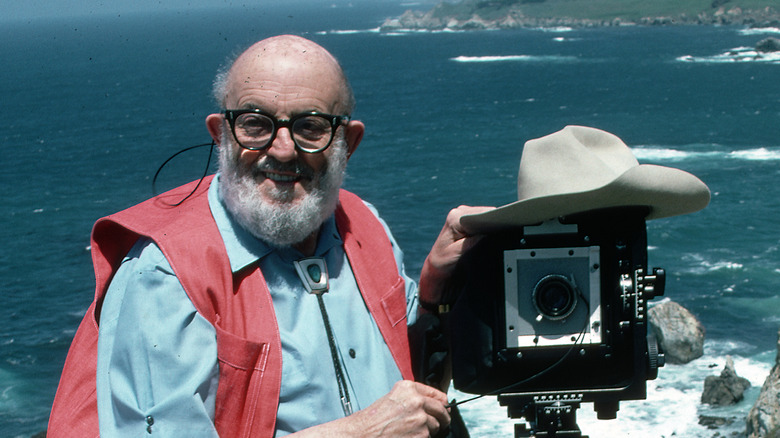

The Untold Truth Of Ansel Adams

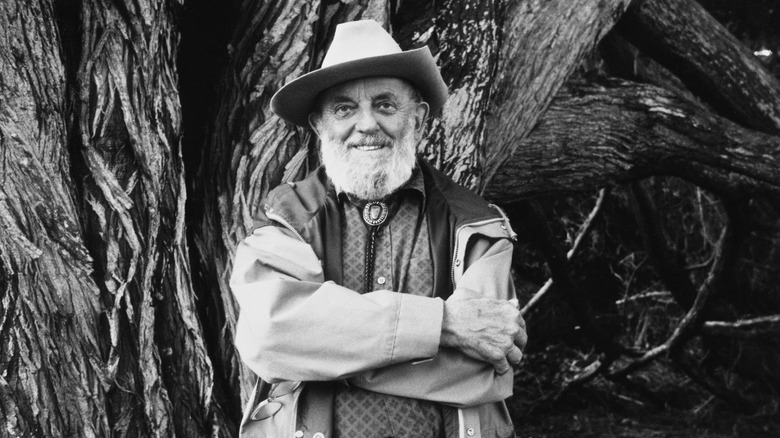

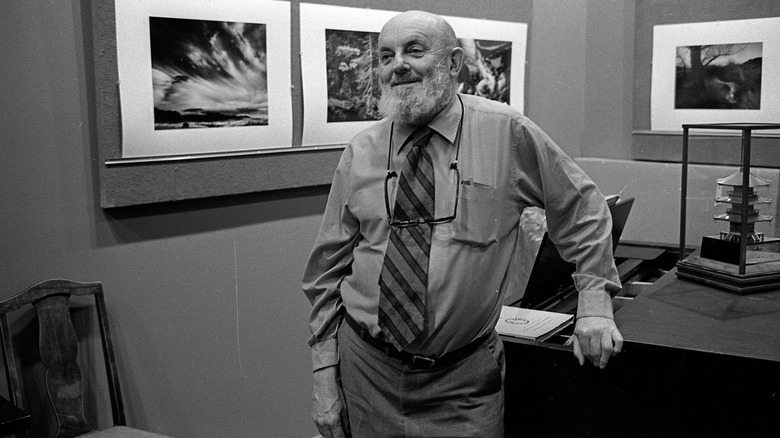

Photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984) is best known for his magnificent shots of America's natural landscape and his devotion to environmental conservation. In almost every aspect of his life, he defied labels. His beliefs crossed parties and policy, and rarely did he cave to extremes — except when his beloved wilderness was at risk.

Adams was uncompromising on two issues. As the descendant of founding-stock New Englanders, he believed the Declaration of Independence's promise that "all men are created equal" was literal and sacrosanct. Second, he had no tolerance for seeing America's unspoilt lands turned into what he once described as "the outskirts of Las Vegas."

Adams' views put him in good company with President Theodore Roosevelt, making the photographer a typical product of that president's era — rugged and rough, yet cultured and nuanced. Roosevelt shared Adams' zeal to preserve America's virgin wilderness together with a firm belief that all were in fact created equal — even if America still had steps to take to reach that goal. Ultimately, Adams was American to the bone — and he lived it until his dying day.

He survived the catastrophic San Francisco earthquake of 1906

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake ignited a blaze that burned much of the California city to the ground, killed around 3,000 people, and left more than half of the city's population homeless. Among the survivors was Ansel Adams, whose home miraculously withstood the disaster. In his autobiography, the photographer wrote that he awoke at 5:15 a.m. to a violent shock, as the earthquake shattered windows and toppled furniture. The tremor destroyed the chimney, which collapsed onto his father's recently completed greenhouse. The walls, however, remained intact.

The earthquake left Adams with a permanent nose injury. After the initial tremor, the Adams family moved the kitchen outside, because cooking on a wood stove after an earthquake was a fire risk due to aftershocks — despite the concussed cook's attempts to do just that. As the family was sitting outside, an aftershock threw the 4-year-old Adams against a brick garden wall, causing a bleed that took an hour to stop and shattered his septum.

Looking back, Adams reacted to the adverse situation as he often did — with go-with-the-flow humor. In his autobiography, he wrote, "... my beauty was marred forever — the septum was thoroughly broken. When the family doctor could be reached, he advised that my nose be left alone until I matured ... Apparently I never matured, because I have yet to see a surgeon about it."

He rejected organized religion because of his Greek tutor

The Adams family did not subscribe to an organized religion. In fact, Ansel Adams' religious beliefs could be described as an eclectic mix of the American transcendentalism of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson – people who believed one could encounter the divine in nature — and the idea from President Theodore Roosevelt's time that a "new" America was being forged in the pristine wilderness of the Western Frontier.

While Adams' father imparted some of these beliefs to his son, the photographer credited his Greek tutor, the Rev. Dr. Herriot, with his disdain for organized religion. Adams wrote in his autobiography that the two frequently debated the personal vs. institutional nature of religion. "Dr. Herriot assumed I went to church," he wrote. "It did no good to explain that I was an agnostic, to him a heathen. My disregard of conventional faith was incomprehensible to him."

Adams used evolution as an example. Dr. Herriot accepted the pre-Darwinian idea that the Earth was roughly 4,000 years old, while Adams accepted evolution and the fossil record, which his tutor dismissed as a test of faith. Dr. Herriot's obstinance convinced Adams that organized religion and its rigidity "all were at huge variance with the luminance of music, the revelations of philosophy and poetry, the freedom of the rolling hills and the ocean." This attitude echoed Emerson's essay "Nature," which bemoaned "innocent men who worship God after the tradition of their fathers" rather than redeeming their souls in the beauty of God's creation.

He credited homeschooling with his success

Ansel Adams struggled in the world of formal education, bouncing from school to school. He characterized school in general as a creativity-killing bore. Rather than learning facts that seemed to have no practical purpose, he preferred to be playing outside. In his autobiography, he complained that formal education was no education at all, since it stripped the student of all passion and desire to learn — at least in his case. In response to his son's troubles, Charles Adams decided to homeschool Ansel, focusing primarily on French and English classics, while the Rev. Dr. Herriot taught him Greek. Ansel wrote that homeschooling was a lifesaver and taught him how to think, crediting his religious debates with his Greek teacher for "stimulat[ing his] intellectual and imaginative faculties."

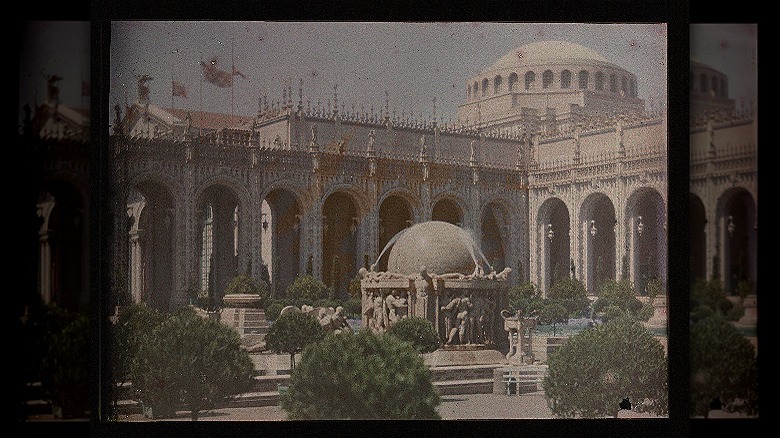

Ansel found a new "school" when the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (pictured) came to San Francisco in 1915, He loved it, imbibing everything he could from exhibits on subjects such as art, architecture, science, and engineering. To young Ansel, the best teachers were the curators, who were happy to answer all questions and explain anything confusing. He even met a man who made him promise to keep a secret that was likely related to the man's involvement in the 1916 Preparedness Day Bombing.

Ansel was eternally grateful to his father, writing, "I often wonder at the strength and courage my father had in taking me out of the traditional school situation and providing me with these extraordinary learning experiences." He eventually earned the equivalent of an eighth grade diploma.

He credited piano with setting him straight

In his autobiography, Ansel Adams described himself as a "hyperactive Sloppy Joe" who seriously needed structure in his life. Music turned out to be that needed structure when his father enrolled him in piano lessons with a woman named Marie Butler.

Butler, Adams wrote, appeared sweet and soft spoken, but when it came to teaching piano, she was merciless. Instead of letting him learn his preferred way, which no doubt would have involved letting him do what he felt like, when he felt like it, she drilled him incessantly. "She was very patient with problems of interpretation," Adams wrote. "But to not have the correct notes or rhythms was unforgivable." In short, she demanded perfection — something that would transfer to Adams' photography later on in life.

Just as with school, the drills bored Adams to death because they seemed completely pointless to him. But despite the boredom, Adams stuck with the lessons. One day, he realized he was actually getting better — and not just his piano playing. His ability to concentrate, even on things that seemed boring at first, improved too. By 1923, he claimed, he was on track to become a professional pianist, but ultimately settled on a career in photography instead.

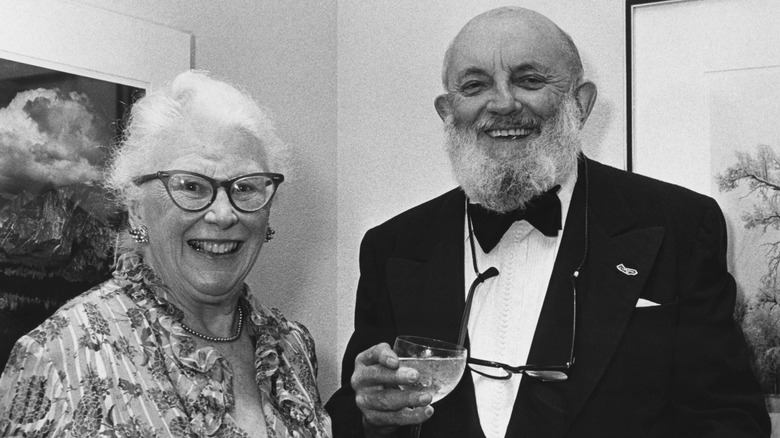

HIs best man nearly derailed his wedding

In 1921, Ansel Adams was looking for a place to practice piano while vacationing in Yosemite National Park. Local resident Harry Best allowed him to practice on his. There, he met Best's 17-year-old daughter Virginia, who was training to be a classical singer. The pair were gradually drawn to each other over their shared interests in music, hiking, and environmental conservation.

It seems Adams loved Virginia, but refused to marry her immediately. Their first engagement fell through, perhaps because the photographer was on shaky ground financially and career-wise. After dating for six years, the pair got engaged on New Year's Eve 1927 and were married three days later in 1928. They eschewed the usual trappings in the interest of time. Virginia did not wear the traditional white dress, while Adams paired his shirt and tie with the bizarre combination of knickers and basketball shoes, a move he credited to his disdain for "traditional" wedding and societal norms in general.

Although the ceremony went forward without a hitch, it nearly ran into disaster beforehand. Adams' best man lost the wedding ring in the snow, only finding it right before the ceremony's start. The couple then suffered a flat tire on the way back to California, but the jack did not work. So, they ripped a mailbox out of the ground and used its post to lift the car and change the tire. Despite the rocky start, the marriage produced two children and survived until Adams' death in 1984.

He smoked out a kindergarten early in his career

Early on in his career, Ansel Adams scraped by earning a living as a commercial photographer, writing in his autobiography (via Ansel Adams Gallery), "Our bank account would dwindle to a distressing level and I would grow deeply concerned, then ... the phone would ring and an assignment would present itself." One of those early jobs — his first paid professional assignment — was in 1920, when one Miss Lavolier, a kindergarten teacher at the Baptist Chinese Grammar School in San Francisco, asked Adams to photograph her class inside her classroom.

Adams arrived on site and realized a good indoor picture would require additional artificial light. The modern flashbulb, however, was not invented until 1925, so Adams, who had little experience with flash photography, had to generate flash using what today are regulated explosives — black powder cap detonators (the kind of stuff used in dynamite) and the highly flammable, spontaneous combustion-prone magnesium flash powder. These were not materials an inexperienced photographer should have been handling, especially around children.

The entire endeavor nearly ended in disaster. Adams used several times the necessary amount of powder, resulting in a flash he described as "apocalyptic," smoking out the room, and sending the kids running for the cover of their desks. Fortunately, no one was hurt, and after a visit from the San Francisco Fire Department, Adams decided to photograph the class outside using his preferred natural light — without the worry of rogue incendiary devices.

He called a rival photographer the Antichrist

Ansel Adams embraced realism in photography, which meant photographing real subjects (e.g., people and places), as they were, without image manipulation to turn it into something more abstract, idealized, or grotesque. Adams' rival, William Mortensen, however, embraced fantastical erotic and occult subject matter over representations of physical reality. He manipulated his photos to make them more "grotesque" to the point that they looked more like drawings than real images, resulting in finished products like his famous "L'Amour." This photo depicted a bare-breasted woman in a supine position below a giant ape. Other examples depicted witchcraft, satanism, and the occult.

Adams hated Mortensen not because of his dark subject matter, but because he thought Mortensen was defeating the point of photography. Adams believed that photography was a record of reality. Mortensen saw realist photos as a starting point for the creation of art transcending physical reality. By manipulating his images into prints of non-existent, grotesque subjects, Mortensen was turning photography on its head, which Adams likened to something satanic. If realism was photography at its purest, then Mortensen was the "Anti-Christ of Photography," according to Adams — the polar opposite of realism embodying everything wrong with the art.

The two men disliked each other so much that according to Smithsonian Magazine, when Edward Weston wrote to Adams about a photo of a corpse, Adams' "only regret [was] that the identity of said corpse [was] not our Laguna Beach colleague."

He viewed WWII as a quasi-sacred war for human equality

Although Ansel Adams opposed nuclear weapons, he supported the Second World War, which ironically ended with two nuclear bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Not only did Adams support the war — he viewed it almost as a sacred struggle for human equality.

In his book "Born Free and Equal," which depicted life in the Manzanar Japanese American internment camp, Adams wrote that the centerpieces of liberty were inalienable individual rights possessed by all, regardless of race or ethnic background. Racially tinged totalitarianism, embodied in the trio of Italy (the Fascist), Germany (the Nazi), and Japan (the Militarist) was the biggest enemy of these rights. Thus, America's purpose in World War II was to defend individual rights worldwide by any means necessary. By punishing the violators — especially those who cited ethno-racial justifications — the U.S. would send a message that atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking, the massacre at Lidice, and the Holocaust would not be tolerated.

Adams' book was censored to avoid depicting certain features of the camps, such as guard towers and barbed wire fencing. But the fact that Adams went to photograph Japanese American internees, who were deprived of their rights on the basis of ethnic origin, suggests that his support of the war as a way to eliminate racial hatred was genuine. A world divided by racial and ethnic strife of the kind seen in Europe and Asia was not exactly conducive to Adams' ideal of humans living in harmony with each other and nature.

He wanted America to live up to its ideals

Ansel Adams' book "Born Free and Equal" argues at the end that the United States was in the Second World War to defend human freedom and equality. Unsurprisingly, Adams was an unwavering defender of the Declaration of Independence's central promise -– "that all men are created equal [and] endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Adams vehemently criticized the United States by proxy for its failure to live up to the Declaration's words, letting the greats of the past talk for him. The book opens with Sec. 1 of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship rights for all Americans, including the Declaration's promises of life and liberty, alongside property. These rights were God-given, inviolable, and sacred — a point Adams drove home at the end of his book. Japanese American internment camps were an egregious violation of this founding principle. Adams also quoted Abraham Lincoln's speech about the nativist Know-Nothing Party, in which the late president decried the idea that Americans of his time seemed to read the Declaration as "'all men are created equal, except Negroes'" while warning that, should nativist factions be elevated to power, "it will read 'all men are created equal, except Negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.'"

In this vein, Adams noted that if America was to win the Second World War — a war against ethno-racial hatred — then it had to win against these hatreds on the homefront. Otherwise, the sacrifices made to defeat them abroad would be in vain.

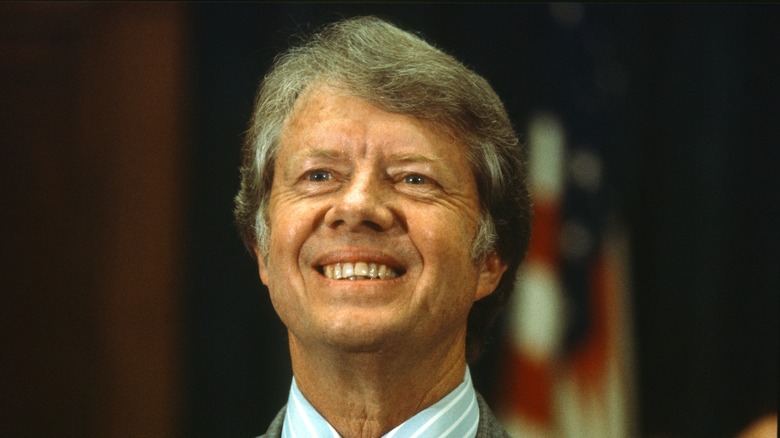

Jimmy Carter had him take the presidential portraits to save money

The presidential portrait is usually an oil-on-canvas painting. But according to a 1979 Washington Post story, President Jimmy Carter broke with tradition, figuring it would cost less to do a photo shoot instead. One version credits Carter with the idea, as he could present himself as a hawk on wasteful spending. The National Archives credits Second Lady Joan Mondale, who wanted to patronize photography. Either way, there was no need to hire a painter or a photographer — Ansel Adams was willing to do it for free.

The photo shoot went swimmingly, even according to the exacting Adams, who revealed some of his more amusing moments to Vice President Walter Mondale. During that session, Adams opined that Mondale was very photogenic and mentioned that he had once photographed hotel magnate Conrad Hilton — his worst-ever subject because he only gave Adams five minutes of his time.

During the session with the president, Adams said he was unable to get Carter positioned just right, so he went and gently pushed Carter into place. The Secret Service immediately stopped him — touching the president was a potential security threat. Despite the incident, Adams wrote that the shoot was "a delightful personal experience" and that he "was amazed at the impression of relaxation, warmth and self-possession [Carter] gave at all times and which was so gratifyingly revealed in the portraits." Adams' photo of Carter served as his presidential portrait until 1982, when a traditional oil-on-canvas portrait was unveiled with little pomp and no ceremony.

He masterminded one of Jimmy Carter's proudest achievements

During the photo shoot for Jimmy Carter's presidential portrait, Ansel Adams presented Carter with two memos (via the National Archives) urging the administration and Congress to block residential and energy development on yet-unspoiled lands in California and Alaska. For Adams, the issue of California's Big Sur coast hit close to home, writing in that memo, "As a photographer, a conservationist and a nearby resident, I have long had a very deep personal interest in the protection of this magnificent, rugged coast."

In 1980, soon after giving Carter the memos, Adams was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his conservation efforts. Although happy for the recognition, privately, Adams still had misgivings about the Carter administration's efforts. In June 1980, he complained that despite Carter's assurances of White House support for the conservation of Big Sur, "Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Rupert Cutler was quite negative, and left a clear impression that the White House did not support Big Sur legislation." In the end, the legislation died in the Senate amid opposition from California's senatorial delegation.

Adams was more successful in Alaska. In 1980, Congress passed, and Carter signed, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which designated millions of acres of federal land as wildlife refuges, national parks, and other protected wilderness. Sec. 1003 explicitly banned oil and gas production, although it exempted pipelines passing through. Carter was delighted, calling the legislation one of his proudest and most enduring achievements.

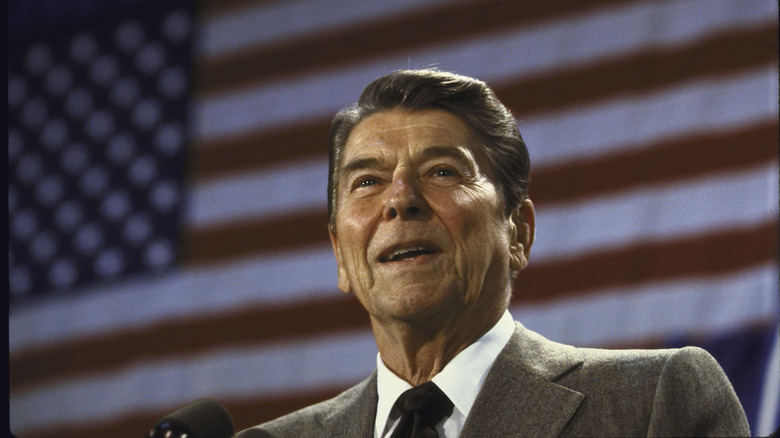

Ansel Adams liked Ronald Reagan, despite disagreeing with him

Ansel Adams' environmental activism placed him at loggerheads with the Ronald Reagan administration, whose drive to privatize and deregulate the oil industry threatened Adams' accomplishments under the Carter administration. According to a 1983 Washington Post story, Adams lobbied Congress incessantly while writing daily op-eds in local newspapers about "the Pearl Harbor of our American Earth" Reagan would unleash on the country. The White House ignored him until he told Playboy, "I hate Reagan."

In response, Reagan sought a conversation with Adams, from which both men walked out seeming to respect each other. Their impressions, however, were very different. Adams liked the president. "He was very amiable, very sincerely cordial," he said. "He was a gentleman, he'd be a nice neighbor." But he added that it was impossible to find common ground due to "that stone wall when someone has a totally different concept of the world," suggesting the talk accomplished little.

The Reagan administration claimed that the president had addressed and "dulled" all of Adams' environmental concerns. Reagan also claimed that Adams had asked to meet him, rather than the other way around. The inconsistencies between the two testimonies can be summed up as what The Washington Post called "the president trying to cope with a critic, and a critic trying to cope with the president." Presumably, they both wanted to walk out looking like winners in the court of public opinion.

He considered Reagan's interior secretary James Watt public enemy No. 1

Ansel Adams had nothing good to say about Ronald Reagan's interior secretary James Watt (pictured), whom he considered the root of the administration's unrestricted expansion of oil drilling on federal lands. In a 1981 op-ed for the San Jose Mercury (via BluePlanet Photography), Adams called Watt "the most intense threat we have ever faced to the integrity and future of our land." Adams slammed Watt as a short-sighted religious fundamentalist ignorant of the National Park system he managed. In the op-ed, he wrote that Watt "justifie[d] his program of using our land and resources now without regard for the future by saying, in effect, there will be very little future; the Second Coming is due any time now." Adams argued the secretary was imposing his religious views upon Americans who supported long-term conservation efforts and did not believe in the Rapture.

Despite his seeming anti-oil rhetoric, Adams supported exploiting natural resources, including oil. In the same op-ed, he wrote that nature provided a bounty of natural resources for humans to use. Humans just had to use them sustainably to avoid depleting them and destroying nature's beauty in the process. This was Theodore Roosevelt's philosophy, after which Adams believed America's modern environmental policies should be modeled.

Despite his criticism of Watt, Adams went easy on Reagan himself, writing, "The overwhelming problems of our economy and defense have taken precedence ... I sympathize with the President in his difficult economic and political decisions."

He was a major advocate of nuclear power

Ansel Adams opposed excessive use of fossil fuels not just due to pollution concerns, but because he thought unrestrained exploitation would burn through U.S. energy reserves. But he broke with the movement on nuclear power, telling David Sheff in a 1983 interview that it was a cheap, clean, fossil-fuel alternative. In the interview, Sheff brought up several concerns about nuclear power, chiefly whether radiation was a health and environmental hazard, whether it was safe — the 1979 partial meltdown at Three Mile Island was still a fresh memory — and whether nuclear waste could be properly disposed of.

Adams largely dismissed concerns about nuclear power, especially attempts to link civilian usage of nuclear technology with weapons of mass destruction. He appeared to suggest that the Three Mile Island accident was overhyped (it had negligible health effects on the surrounding area). Poorly trained nuclear technicians were the cause of the accident, not the technology itself. He pointed out that Europe had lots of nuclear plants without any problems, adding that Americans were more likely to die in car accidents than from nuclear meltdowns.

Adams identified private industry as the problem. "The danger is that most of the plants are privately operated and, therefore, under economic stress, and private companies are not likely to spend the money it takes to ensure that the plants are completely safe," he told Sheff. Government regulation and ownership of plants would prevent incidents like Three Mile Island — if people were willing to shoulder higher regulatory costs.

He photographed out of love, not politics

Ansel Adams said in a 1983 interview with David Sheff that his profession as a photographer drove his politics, rather than the other way around. He never took a photograph on behalf of a political cause, because he could not "just ... go out and take a picture of a place because somebody [needed] it for a promotion of some political campaign." His opposition to political involvement writ large led to his resignation from the American Photo League in the late 1940s over its alleged communist sympathies.

Although Adams was mostly apolitical, he encouraged the political use of already-existing photos for environmental causes he supported. In 1936, for instance, there was a major battle over the future of California's Kings Canyon. Developers wanted the land, which Adams bemoaned would turn the area into "the outskirts of Las Vegas." Opponents wanted the land protected, and used Adams' photographs of the area to show the kind of natural beauty that would be lost to another commercial strip. A similar battle unfolded over San Francisco's Golden Gate area.

In his interview with Sheff, Adams' responses suggest his opponents accused him of taking the photos for a political agenda. He maintained, however, that he took the pictures of both places well before development was ever on the table, because he liked the places. It was a happy coincidence that they served his cause later. "I took the photographs independently," he told Sheff, "and, thank God, they were used constructively."

A pro-oil congressman named a pro-individual liberty bill in Adams' honor

Ansel Adams was an environmentalist and an opponent of Big Oil, but he was also a crusader for the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and their guaranteed rights. So, one wonders what Adams would have thought when pro-oil Texas Republican Congressman Steve Stockman (pictured) named a pro-First Amendment bill in the late photographer's honor.

The Ansel Adams Act would have protected photographers' First Amendment right to photograph on federal land by ensuring "Future 'Ansel Adams' [would] not have their paths blocked, regulated and made more expensive with fees and fines, or be threatened with arrest and seizure of their equipment." The law would have forbidden Washington from imposing restrictions or fees on photography on federal lands in places like national parks, except by court order in cases where national security was deemed at risk.

Although the bill had no chance of passing, since it was proposed on the penultimate day of the 113th Congress, it garnered support even among liberal commentators like Esquire Magazine, which praised Stockman's initiative as protecting property rights and ensuring photographers and filmmakers could hold federal agents accountable for bad behavior. Given how much Adams valued individual rights, and his political pragmatism in dealing with Ronald Reagan, it seems safe to conclude that he would have supported the bill — even if he would have opposed Rep. Stockman's other policies.